Published online Nov 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6694

Revised: September 30, 2008

Accepted: October 7, 2008

Published online: November 21, 2008

AIM: To study the sensitivity, specificity and cost effectiveness of barium meal follow through with pneumocolon (BMFTP) used as a screening modality for patients with chronic abdominal pain of luminal origin in developing countries.

METHODS: Fifty patients attending the Gastroenterology Unit, SMS Hospital, whose clinical evaluation revealed chronic abdominal pain of bowel origin were included in the study. After routine testing, BMFT, BMFTP, contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen, barium enema and colonoscopy were performed. The sensitivity, specificity and cost effectiveness of these imaging modalities in the detection of small and/or large bowel lesions were compared.

RESULTS: Out of fifty patients, structural pathology was found in ten. Nine out of these ten patients had small bowel involvement while seven had colonic involvement alone or in combination with small bowel involvement. The sensitivity of BMFTP was 100% compared to 88.89% with BMFT when detecting small bowel involvement (BMFTP detected one additional patient with ileocecal involvement). The sensitivity and specificity of BMFTP for the detection of colonic pathology were 85.71% and 95.35% (41/43), respectively. Screening a patient with chronic abdominal pain (bowel origin) using a combination of BMFT and barium enema cost significantly more than BMFTP while their sensitivity was almost comparable.

CONCLUSION: BMFTP should be included in the investigative workup of patients with chronic abdominal pain of luminal origin, where either multiple sites (small and large intestine) of involvement are suspected or the site is unclear on clinical grounds. BMFTP is an economical, quick and comfortable procedure which obviates the need for colonoscopy in the majority of patients.

- Citation: Nijhawan S, Kumpawat S, Mallikarjun P, Bansal R, Singla D, Ashdhir P, Mathur A, Rai RR. Barium meal follow through with pneumocolon: Screening test for chronic bowel pain. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(43): 6694-6698

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i43/6694.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6694

| Imaging | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| Barium enema | 7/7 (100) | 42/43 (97.67) |

| BMFT with pneumocolon | 6/7 (85.71) | 41/43 (95.35) |

| CT abdomen | 3/7 (42.87) | 41/43 (95.35) |

| Colonoscopy | 7/7 (100) | 43/43 (100) |

Abdominal pain lasting more than 6 mo duration is defined as chronic abdominal pain. Some of these patients have colicky pain or have other associated features in the form of abdominal distension, constipation or vomiting which suggests bowel involvement. The majority of these patients turn out to have functional disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia and functional abdominal pain syndrome. Of these patients, only a few will definitely have organic lesions.

The evaluation of chronic abdominal pain of luminal etiology is a challenging problem for primary care physicians and gastroenterologists. The exact localization of lesions in either the small or large bowel remains difficult in many subjects. In tropical countries, where most of the population is of low socioeconomic status, an imaging modality which screens small and large bowel lesions simultaneously at a reasonable cost and with good sensitivity and specificity is needed. Small bowel evaluation by barium meal follow through (BMFT) and colonic evaluation by double contrast barium enema (DCBE) are the standard norms[1].

The technique of pneumocolon has been used previously to evaluate the terminal ileum and caecum[2-5]. Performing pneumocolon along with BMFT at the same time evaluates both the small as well as the large bowel and is more economical than the combination of BMFT and barium enema. However, its potential in identifying colonic lesions is still controversial[6,7]. We evaluated BMFT with pneumocolon (BMFTP) as a single test for the assessment of chronic abdominal pain of bowel origin, screening both the small and large bowel simultaneously.

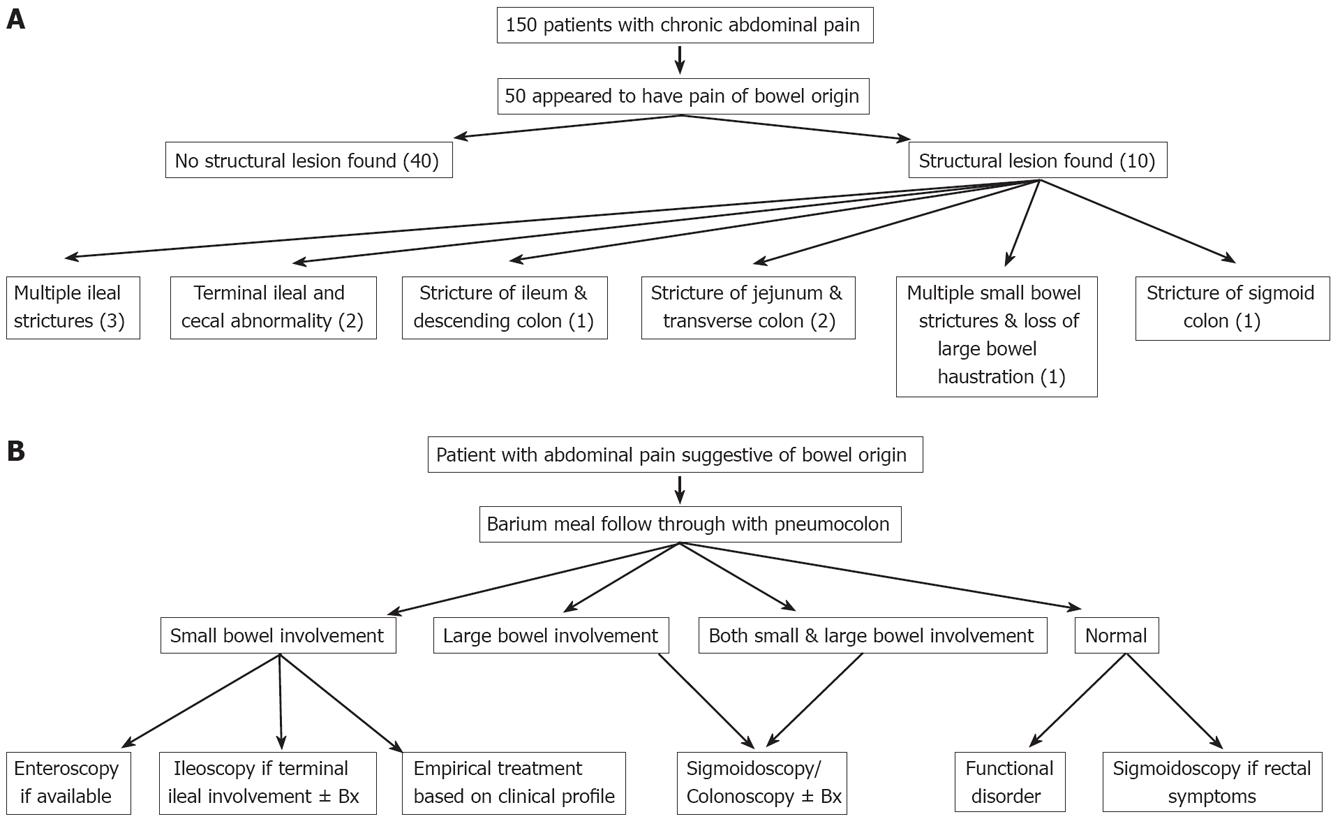

One hundred and fifty consecutive patients with chronic abdominal pain attending the Gastroenterology Unit of SMS Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur were evaluated. A detailed history and thorough physical examination were carried out. Fifty patients in whom clinical evaluation suggested the involvement of the small bowel, large bowel or both were enrolled in the study (Figure 1A). Complete blood count, ESR, chest X-ray, liver function tests, renal function tests, serum amylase and complete examination of stools were performed. BMFT, DCBE, BMFTP and colonoscopy were carried out as per standard protocol. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the whole abdomen was also done. Subjects underwent overnight fasting and were asked to drink 100 mL of oral contrast dissolved in one liter of water around one and a half hours before the procedure. When subjects were taken for CECT, around 1 mL/kg of non-ionic contrast was given intravenously on the CT table. CT cuts were subsequently taken. We compared the sensitivity of these tests in detecting lesions as well as their cost effectiveness.

BMFTP was carried out in a similar way to BMFT. Microbar (Eskay fine chemicals) containing barium sulphate (92%) was used. 175 mg of Microbar powder was stirred in 150 mL of water to make a homogeneous solution. Patients were prepared with laxatives 1 d before the procedure. Preliminary plain abdominal films were taken prior to the procedure to rule out significant obstruction and perforation and to evaluate the patient’s bowel preparation status. Preliminary films of the gastroesophageal junction, stomach and duodenum under IITV control were taken in the prone, supine and oblique positions to rule out diaphragmatic hernia, stomach and duodenum lesions and to assess the position of the duodeno-jejunal flexure. The patient then lay on his right side so that a continuous single column of barium was delivered into the small intestine. Prone postero-anterior (PA) films of the abdomen were taken every 20 min during the first hour and subsequently every 30 min to 45 min until the barium reached the colon[8]. A light dry meal was allowed after the barium had reached the ileum to speed up the examination if transit time was slow. Spot films of the ileocecal junction were also taken if required. Spot films with compression were taken of suspected abnormal bowel loops and strictures if required. When the barium was seen to cross the splenic flexure and the small bowel was almost devoid of barium on fluoroscopy, sufficient air was insufflated rectally using a sphygmomanometer cuff to achieve adequate distention of the colon.

About 300 mL to 450 mL of air was insufflated. Standard antero-posterior (AP), PA and oblique views of the colon were taken to observe the proximal and distal large intestine.

One hundred and fifty patients presented with chronic abdominal pain, of which fifty patients (28 males, 22 females) had bowel symptoms. The mean age of these 50 patients was 35 years (range 25-55 years). Structural pathology was found in only 10 patients (Figure 1A). Caecal deformity along with distal ileal narrowing was seen in 2 patients, multiple ileal strictures in 3 patients, ileal stricture and stricture of the descending colon in 1 patient, multiple small bowel strictures with loss of haustration in most of the large bowel in 1 patient, jejunal and transverse colonic stricture in 2 patients (Figure 2) and stricture of the sigmoid colon in 1 patient. Nine of these ten patients had small bowel involvement while seven had colonic involvement.

BMFT detected 8 of 9 patients (sensitivity = 88.89%) who had small bowel involvement while BMFTP detected one additional patient with ileocecal involvement which was missed on BMFT (sensitivity = 100%).

In 7 patients where colonic pathology was found, BMFTP detected lesions in six patients while DCBE detected lesions in all seven patients. BMFTP gave false-positive results in 2 patients while DCBE was false-positive in one patient. Colonoscopy was normal in these false-positive cases. The sensitivity of BMFTP in the detection of colonic pathology was 85.71% (6/7) and was 100% (7/7) for DCBE. The specificity of BMFTP was 95.35% (41/43) and was 97.67% (42/43) for DCBE (Table 1).

CT scanning of the abdomen revealed small bowel involvement in only four of the nine patients (sensitivity = 44.45%) and colonic lesions in three of seven patients (sensitivity = 42.87%), although CT revealed additional findings including abdominal lymph nodes (4 patients) and a small amount of free fluid in the abdomen (2 patients).

Colonoscopy performed in all fifty patients revealed colonic lesions in seven patients and terminal ileal involvement in two patients. Biopsies taken from various lesions revealed tuberculosis in four patients, two patients had features of Crohn’s disease and one had colonic malignancy.

Screening a patient with abdominal pain suggestive of bowel origin using a combination of BMFT and DCBE cost three thousand rupees (71.43 $) while BMFTP cost eighteen hundred rupees (42.86 $) and the sensitivities were almost comparable. Screening with BMFTP instead of BMFT and DCBE obviates the need for colonoscopy in around 80% of patients.

This study revealed that screening patients with abdominal pain of luminal origin using BMFTP alone was cheaper compared to the combination of BMFT with DCBE and was almost as sensitive and specific. BMFTP obviates the need for colonoscopy in a number of patients as it also screens patients with colonic involvement.

BMFTP was better than BMFT alone in identifying terminal ileal and cecal lesions[9-12]. In a study by Marshall et al[13], BMFTP was found to be as accurate as ileoscopy in diagnosing terminal ileal disease. Minordi et al[14] showed that combining pneumocolon with BMFT improved the identification of terminal ileal and cecal lesions. Taves et al[7] reported two cases of cecal carcinoma which were initially described as Crohn’s disease on the basis of BMFT, but were later diagnosed as malignant by the addition of pneumocolon and further confirmed by colonoscopy and pathology. In this study, we also found that the two patients who had terminal ileum and cecal involvement were both identified by BMFTP while one was missed on BMFT alone.

Adding pneumocolon to BMFT helped in the detection of colonic lesions[15-17]. Previous studies have revealed that BMFTP was better at detecting proximal colonic lesions compared to distal lesions. Chou et al[6] showed that a routine overhead radiograph following the use of the pneumocolon technique was a useful adjunct to small bowel meal examination as it could yield unsuspected and clinically significant colonic findings. Colonic abnormalities such as ascending colonic cancer, acute or chronic colitis, diverticulosis, cecal polyps and ileosigmoid fistula were diagnosed using this pneumocolon technique in their study of 151 patients. Various studies which have combined contrast CT of the abdomen with pneumocolon have been used to evaluate various colonic lesions[18-22]. Some of these studies have shown CT pneumocolon to be a reliable alternative to barium enema where colonoscopy is incomplete, with the added advantage of extra luminal screening, and examination of the proximal bowel[23-25].

In this study, we were able to detect 6 of 7 colonic lesions by adding pneumocolon to BMFT. One of the patients who had sigmoid colonic stricture was missed using this imaging method and was detected by subsequent colonoscopy. Although there is little data available on the role of BMFTP in the detection of colonic lesions, most of the colonic lesions observed in this study were detected by BMFTP.

The findings from this study showed that in a patient with abdominal pain which clinically appeared to be arising from the bowel, that by performing BMFTP, both the small and large bowel were screened at the same time, and that the technique showed an efficacy comparable to that of BMFT combined with DCBE. The BMFTP technique was found to be simple and easy and obtained excellent double contrast visualization of the distal ileum and colon. The rectal and sigmoid areas were difficult to interpret on BMFTP. These patients usually have clinical symptoms suggestive of distal colonic or rectal involvement and they can be investigated with the added procedure of sigmoidoscopy.

In addition, BMFTP obviated the need for colonoscopy in the majority of patients as most of these patients were ultimately found to have functional disorders. Colonoscopy should only be performed in those patients who have positive findings on BMFTP, thereby decreasing the cost significantly. Colonoscopy is an invasive technique with significant procedure-associated discomfort.

Common luminal diseases of the gut such as tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease involve more than one site in the bowel. Imaging requires the screening of both the small and large bowel for these diseases and effects therapeutic decisions. BMFTP helped in the investigation of these diseases by screening the whole lumen at one time. This study revealed that many patients who had strictures at multiple sites were successfully detected by BMFTP.

Based on our findings, we proposed a step-up approach for investigating patients with chronic abdominal pain of bowel origin (Figure 1B). Patients presenting with chronic abdominal pain of luminal nature in whom involvement of both the small and large bowel is suspected or where differentiation between the two is not possible, BMFTP should be performed after all baseline investigations. If BMFTP reveals only small bowel involvement, then depending on whether the terminal ileum is involved, patients should undergo ileo-colonoscopy with biopsy or enteroscopy. When terminal ileum is not involved and enteroscopy is unavailable, then patients should undergo empirical treatment based on their clinical profile. On the other hand, if BMFTP shows associated or isolated large bowel involvement, colonoscopy with biopsy of the lesion should be performed. By following this algorithm, one can investigate these patients in a cost effective manner which carries great significance for poor developing nations.

In tropical countries where the majority of the population is of low socio-economic status, BMFTP should be included in the investigative workup of patients with chronic abdominal pain of luminal origin, where either multiple sites (small and large intestine) of involvement are suspected or the site is unclear on clinical grounds. BMFTP is an economical, quick and comfortable procedure and obviates the need for colonoscopy in the majority of patients.

Few studies have tried to evaluate barium meal follow through (BMFT) with pneumocolon as a screening modality in subjects with chronic abdominal pain of luminal origin in developing countries where an inexpensive and cost effective screening tool is needed. Only a few studies have compared BMFT with pneumocolon vs plain BMFT for imaging ileocecal areas and the results of these studies have been varied.

Evaluating small and large bowel simultaneously with a cost effective screening modality in developing countries is needed, as costly invasive modalities like double balloon enteroscopy and colonoscopy can be used only in selected subjects.

This is the first study to evaluate BMFT with pneumocolon as a screening tool for the evaluation of chronic abdominal pain of bowel origin. Adding pneumocolon to BMFT not only helped in detecting ileocecal lesions but also helped to detect colonic lesions with a sensitivity of 88.89% and a specificity of 95.35%.

This study showed that including BMFTP in the investigative workup of patients with chronic abdominal pain of luminal origin, where either multiple sites (small and large intestine) of involvement are suspected or the site is unclear on clinical grounds, helps in screening both the small and large bowel simultaneously and effectively without adding much to the total cost. This can be of great value in tropical countries where most of the population is of poor socioeconomic status.

This study from India demonstrates the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of BMFTP compared to other methods in screening patients with chronic abdominal pain. It’s an interesting paper.

| 1. | Maglinte DD, Kelvin FM, O'Connor K, Lappas JC, Chernish SM. Current status of small bowel radiography. Abdom Imaging. 1996;21:247-257. |

| 2. | Kressel HY, Evers KA, Glick SN, Laufer I, Herlinger H. The peroral pneumocolon examination. Radiology. 1982;144:414-416. |

| 3. | Kelvin FM, Gedgaudas RK, Thompson WM, Rice RP. The peroral pneumocolon: its role in evaluating the terminal ileum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;139:115-121. |

| 4. | Fitzgerald EJ, Thompson GT, Somers SS, Franic SF. Pneumocolon as an aid to small-bowel studies. Clin Radiol. 1985;36:633-637. |

| 5. | Stringer DA, Sherman P, Liu P, Daneman A. Value of the peroral pneumocolon in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:763-766. |

| 6. | Chou S, Skehan SJ, Brown AL, Rawlinson J, Somers S. Detection of unsuspected colonic abnormalities using the pneumocolon technique during small bowel meal examination. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:459-464. |

| 7. | Taves DH, Probyn L. Cecal carcinoma: initially diagnosed as Crohn's disease on small bowel follow-through. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:337-340. |

| 8. | Yong AA, Harris JE, Shorvon PJ. The value of prone imaging in CT pneumocolon. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:959-963. |

| 9. | Cozzi G, Bellomi M, Balzarini L, Severini A. [Oral pneumocolon in the study of the last ileal loops and the ileocecal region]. Radiol Med. 1984;70:204-207. |

| 10. | Wolf KJ, Goldberg HI, Wall SD, Rieth T, Walter EA. Feasibility of the peroral pneumocolon in evaluating the ileocecal region. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:1019-1024. |

| 11. | Marshall JK, Hewak J, Farrow R, Wright C, Riddell RH, Somers S, Irvine EJ. Terminal ileal imaging with ileoscopy versus small-bowel meal with pneumocolon. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:217-222. |

| 12. | Tolan DJ, Armstrong EM, Bloor C, Chapman AH. Re: the value of the per oral pneumocolon in the study of the distal ileal loops. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:603; author reply 604. |

| 13. | Marshall JK, Cawdron R, Zealley I, Riddell RH, Somers S, Irvine EJ. Prospective comparison of small bowel meal with pneumocolon versus ileo-colonoscopy for the diagnosis of ileal Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1321-1329. |

| 14. | Minordi LM, Vecchioli A, Dinardo G, Bonomo L. The value of the per oral pneumocolon in the study of the distal ileal loops. Clin Radiol. 2006;61:1016-1022. |

| 15. | Mittal A, Saha MM, Pandey KK. Peroral pneumo colon--a double contrast technique to evaluate distal ileum and proximal colon. Australas Radiol. 1990;34:72-74. |

| 16. | Kellett MJ, Zboralske FF, Margulis AR. Per oral pneumocolon examination of the ileocecal region. Gastrointest Radiol. 1977;1:361-365. |

| 17. | Calenoff L. Rare ileocecal lesions. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1970;110:343-351. |

| 18. | Coakley FV, Entwisle JJ. Spiral CT pneumocolon for suspected colonic neoplasms. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:666. |

| 19. | Amin Z, Boulos PB, Lees WR. Technical report: spiral CT pneumocolon for suspected colonic neoplasms. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:56-61. |

| 20. | Harvey CJ, Amin Z, Hare CM, Gillams AR, Novelli MR, Boulos PB, Lees WR. Helical CT pneumocolon to assess colonic tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1439-1443. |

| 21. | Miao YM, Amin Z, Healy J, Burn P, Murugan N, Westaby D, Allen-Mersh TG. A prospective single centre study comparing computed tomography pneumocolon against colonoscopy in the detection of colorectal neoplasms. Gut. 2000;47:832-837. |

| 22. | Britton I, Dover S, Vallance R. Immediate CT pneumocolon for failed colonoscopy; comparison with routine pneumocolon. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:89-93. |

| 23. | Harvey CJ, Renfrew I, Taylor S, Gillams AR, Lees WR. Spiral CT pneumocolon: applications, status and limitations. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:1612-1625. |

| 24. | Sun CH, Li ZP, Meng QF, Yu SP, Xu DS. Assessment of spiral CT pneumocolon in preoperative colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3866-3870. |

| 25. | Low VH, Howard MH, Sheafor DH. Air insufflation: a useful adjunct to the single contrast barium enema for the evaluation of the rectum. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:46-50. |

Peer reviewer: Rami Eliakim, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Rambam Medical Center, PO Box 9602, Haifa 31096, Israel

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Yin DH