Published online Nov 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6366

Revised: September 16, 2008

Accepted: September 23, 2008

Published online: November 7, 2008

AIM: To determine the most frequent etiologies of hepatic epithelioid granulomas, and whether there was an association with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV).

METHODS: Both a retrospective review of the pathology database of liver biopsies at our institution from 1996 through 2006 as well as data from a prospective study of hepatic fibrosis markers and liver biopsies from 2003 to 2006 were reviewed to identify cases of hepatic epithelioid granulomas. Appropriate charts, liver biopsy slides, and laboratory data were reviewed to determine all possible associations. The diagnosis of HCV was based on a positive HCV RNA.

RESULTS: There were 4578 liver biopsies and 36 (0.79%) had at least one epithelioid granuloma. HCV was the most common association. Fourteen patients had HCV, and in nine, there were no concurrent conditions known to be associated with hepatic granulomas. Prior interferon therapy and crystalloid substances from illicit intravenous injections did not account for the finding. There were hepatic epithelioid granulomas in 3 of 241 patients (1.24%) with known chronic HCV enrolled in the prospective study of hepatic fibrosis markers.

CONCLUSION: Although uncommon, hepatic granulomas may be part of the histological spectrum of chronic HCV. When epithelioid granulomas are found on the liver biopsy of someone with HCV, other clinically appropriate studies should be done, but if nothing else is found, the clinician can be comfortable with an HCV association.

- Citation: Snyder N, Martinez JG, Xiao SY. Chronic hepatitis C is a common associated with hepatic granulomas. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(41): 6366-6369

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i41/6366.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6366

| Diagnosis | Number of patients |

| HCV | 9 |

| Histoplasmosis | 4 |

| Sarcoidosis | 3 |

| HIV alone | 2 |

| HCV/HBV | 2 |

| HCV/HIV | 2 |

| Mycobacterium avium | 2 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 2 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Tuberculosis | 1 |

| Coccidiomycosis | 1 |

| Cryptococcus | 1 |

| HBV | 1 |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1 |

| Q Fever | 1 |

| Mucormycosis | 1 |

| Drug induced | 1 |

| Age (yr) | Gender | Fibrosis stage | Granuloma location | Comments |

| 46 | Female | F3 | Portal tract | Multiple |

| 54 | Male | F2 | Lobule | Multiple |

| 46 | Male | F2 | Portal tract | Single |

| 52 | Female | F1 | Diffuse | ↑ alkaline phos |

| 51 | Female | F1 | Portal tract | Single |

| 45 | Male | F1 | Lobule | Multiple |

| 67 | Male | F1 | Portal tract | Multiple, refractile |

| Crystals | ||||

| 47 | Male | F1 | Portal tract | Multiple |

| 37 | Female | F2 | Portal tract | Single |

Epithelioid granulomas are found in 1%-10% of liver biopsy specimens[1-3]. They tend to fall into three broad categories which are systemic granulomatous disease, primary liver disease, or miscellaneous conditions that fit neither category. Hepatic granulomas are sometimes a surprise finding that may trigger an extensive search for an etiology. In some cases the granulomas are associated with a clinical picture which includes a high alkaline phosphatase and hepatomegaly; but these features are frequently absent. A significant percentage of liver biopsies performed today are for the staging of chronic hepatitis C. Granulomas have been reported with possible increased frequency in patients with hepatitis C with both mild disease as well as in explants[4-8]. It has been postulated that hepatitis C virus (HCV) may have a role in granuloma formation[9]. We decided to undertake a retrospective review of cases of hepatic granulomas at our institution during the last decade in order to determine the most frequent etiologies, and also to determine if there was an association with HCV.

Following approval by our institutional review board, we used the data information system in our surgical pathology information system to identify all patients from 1995 through 2005 that had a percutaneous or surgical liver biopsy, and also had the word granuloma or granulomatous in the final diagnosis or in the pathologists description. This data base includes all liver biopsies that are performed at our institution. The University of Texas Medical Branch is a tertiary care institution that consists of 5 hospitals and an outpatient center in Galveston, Texas, USA. Each year it serves patients from most of the counties in Texas, although two thirds of the patients are residents of the Texas Upper Gulf of Mexico Coast. One of the hospitals provides out patient and hospital care to a majority of the inmates in the Texas prison system. No explanted livers were included. We also excluded cases where the biopsy was performed at another institution, but slides were reviewed for a second opinion, and we also excluded several cases where biopsy of ossified nodules at surgery revealed old burned out or inactive granulomas. Autopsies were also excluded. Patients that had only lipogranulomas or small, poorly organized granulomas on their original pathology report were excluded from the study.

Since March 2003, the hepatology service at our institution has been in the midst of a prospective study of hepatic fibrosis markers in patients undergoing pretreatment liver biopsies in chronic HCV. Some of the results of this study have been published[10,11]. This data base was searched as well for patients with evidence of hepatic granulomas on liver biopsy.

When appropriate, charts, reports, and the liver biopsy slides were reviewed. We tabulated information on special stains and cultures that were obtained on the specimens. All patients with hepatic granulomas had their biopsies examined with polarized light for crystalloid particles[12]. Clinical data was assessed to determine HCV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status. The diagnosis of HCV was based on the presence of serum HCV RNA[13]. Information was also recorded regarding the patient’s HCV genotype and routine liver tests. The stage of fibrosis based on the Batts Ludwig (F0-F4) staging system[14] was also noted.

There were a total of 4578 liver biopsies performed at our institution during this time. There were 36 (0.79%) patients identified from the surgical pathology review that had at least one hepatic epithelioid granuloma (Table 1). Special stains were performed in 26 f and tissue cultures in five. The associated diagnoses are listed in Table 1. The most common association was HCV. Fourteen (36.1%) had HCV, and nine of these had no other clinical associations to explain the granulomas. Five of the HCV patients had other confounding associations including chronic hepatitis B, sarcoidosis, histoplasmosis, and HIV (2 patients). The etiologies with more than one case in the non HCV patients were sarcoidosis (3), histoplasmosis (4), primary biliary cirrhosis (3), HIV only (2), mycobacterium avis complex (2), and primary biliary cirrhosis (2), and unidentifiable (2).

There were 241 patients with chronic HCV that had liver biopsies while enrolled in the prospective hepatic fibrosis study during 2003-2006. Three (1.24%) had granulomas, and all of these had been identified in the above database search.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the 9 patients with HCV, hepatic granulomas, and no other identifiable associations. All of the patients had special stains performed on their liver biopsies, and only one had a crystalloid substance noted on polarizing light. Eight of the patients had genotype 1, and the fibrosis stages F1, F2, and F3 were all present in at least one patient. None of the patients had cirrhosis. One patient with diffuse granulomas had an alkaline phosphatase consistently twice normal. Otherwise the liver function tests were typical of chronic HCV.

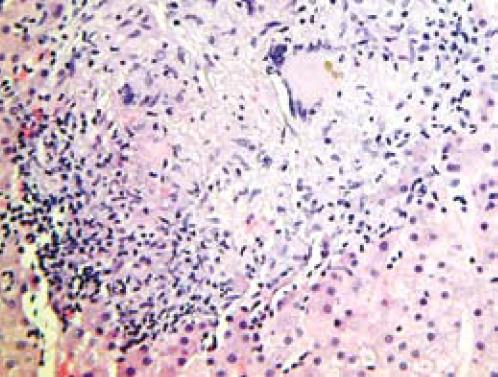

The histologic findings in the patients with HCV only were variable. Figure 1 shows a large granuloma in an asymptomatic patient with mild elevation of ALT that had a staging liver biopsy. The granulomas were present in the portal area in 6 patients, the hepatic lobule in 2 patients, and diffusely in both the portal tract and lobule in one patient. In three patients, there was only a solitary granuloma in the portal tract, while in the others there were multiple granulomas. The case that had crystalloid substance on polarized light had multiple portal granulomas.

We found granulomas in less than 1% of our liver biopsies. Other reports have found granulomas in up to 10% of liver biopsies[1-3]. The frequency of detection as well as the frequency of various diagnoses can depend upon the geographic location of the center and the diseases endemic in that area as well as the diligence of the histopathology laboratory and the pathologists that prepare and examine the slides. Previous studies of hepatic granulomas have primarily been from eras before HIV and widespread organ transplantation, and before HCV became prominent. Although the percentages varied, sarcoidosis and tuberculosis tended to be most common associated diseases reported. A study from our institution from another era found that tuberculosis accounted for 53% and sarcoidosis 12% of the cases of hepatic epithelioid granulomas while in 20% no etiology could be determined[1]. In a large series of 565 cases of epithelioid hepatic granulomas in over 6000 biopsies accumulated over 4 decades, Klatskin[2] found that 36% had sarcoidosis, 12% had tuberculosis and 7% were undiagnosed. While our study indeed found 3 patients with sarcoidosis and another with M. tuberculosis, most cases were associated with HCV or HIV with associated infections.

There have been several reports of granulomas in the liver biopsies of patients with HCV and no other known systemic or hepatic diseases. This may not be unexpected since the most common reason for liver biopsies at most institutions today is staging of chronic HCV, and some unexplained granulomas have long been found on liver biopsies. On the other hand, the concurrence of HCV and granulomas may be frequent enough to not be simply explained by chance. A large recent retrospective review found epithelioid granulomas in 63 of 1662 liver biopsies[5]. While primary biliary cirrhosis (23.8%), sarcoidosis (11.1%), and unknown (11.1%) were the most common associations, HCV was associated with 9.5% of the cases. Emile et al[9] found that the explants of 5 of 52 patients undergoing liver transplantation for cirrhosis from HCV had epithelioid granulomas, and none of these patients had evidence of any other diseases such as tuberculosis or sarcoidosis. Goldin et al[4] found in a retrospective study that there were granulomas in the liver biopsy specimens of 14/155 patients with HCV compared with only 3/151 with HBV and 3/129 with alcoholic liver disease. Yamamoto et al[6] found unexplained granulomas in 2/273 (0.73%) liver biopsies of patients with chronic HCV. In a more recent study from Turkey, 8/605 (1.3%) of patients with chronic hepatitis C had unexplained granulomas on liver biopsy[7]. This is the same percentage that we found among chronic HCV patients in our prospective study of hepatic fibrosis markers that underwent liver biopsies over a three year period. Consequently, it has been postulated that hepatic granulomas may themselves be part of the histologic picture of chronic HCV, albeit uncommonly. Our finding that 9 of 36 patients with hepatic epithelioid granulomas had HCV as their only disease association would support this. We cannot rule out that some of these patients could have had other undiagnosed disorders such as sarcoidosis; but in follow up, none of them have manifested pulmonary or systemic findings to support another diagnosis.

Alpha interferon in regular or pegylated form has been used in the therapy of chronic HCV since the discovery of the virus[13]. It has been speculated that interferon itself can stimulate granuloma production, and there are several reported cases of the development of sarcoidosis in patients receiving interferon therapy[15-19]. This is thought to be related to the ability of interferon to stimulate a Th 1 immune response which is felt to be responsible for the granulomas in sarcoidosis[20]. Both the sarcoidosis and granulomas have usually regressed when interferon was stopped. It is unlikely that interferon usage played a major factor in our patients since only one subject with chronic HCV and granulomas had received interferon prior to liver biopsy.

Intravenous drug use is the most common route of transmission of chronic hepatitis C[21]. Since granulomas can be induced by foreign substances that might be used in a “street prepared” illicit drug mixture, we examined all the slides of patients with HCV and granulomas with polarized light, and a crystalloid substance was found in only one patient. Therefore, foreign body induced granulomas do not appear to be an explanation for most of the granulomas found in our patients with HCV.

We realize that there are problems interpreting the results of a retrospective study such as ours. The majority of the liver biopsies that we perform are on patients that are being staged prior to proposed treatment for chronic HCV. Therefore, the finding of otherwise unexplained granulomas in multiple patients with chronic HCV may not be that unusual or surprising. Nevertheless, in this study the most common association of hepatic granulomas was chronic HCV.

We would recommend if a patient with chronic HCV should have granulomas on liver biopsy that a search for another disease should be made by utilizing special stains and other clinically appropriate tests such as a chest X-ray. However, if no other abnormality is found, the clinician should be comfortable associating the granuloma(s) with the chronic HCV.

Granulomas have long been curious findings on liver biopsies, and sometimes can trigger exhaustive searches for the etiology. Although there are many causes, sarcoidosis and tuberculosis have been the most frequent associations in previous series.

Recent papers have reported finding granulomas in chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients, and it has been speculated that granulomas may be an uncommon part of the immune response in chronic HCV. This study looked retrospectively at a decade of liver biopsies at the large institution to see what the most common disease associations with hepatic granulomas were. Authors also looked prospectively at the prevalence of granulomas in a series of chronic HCV patients undergoing staging liver biopsies.

The most common association of hepatic granulomas at the institution is chronic hepatitis C. The granulomas were both in the portal area and the lobule, and they were both single and multiple. Although present in only about 1% of liver biopsies of patients with hepatitis C, they should be considered as part of the histologic spectrum of the disease.

The finding of hepatic granulomas on the liver biopsy of someone with chronic HCV does not necessitate an extensive workup. Special stains and pertinent tests such as a chest x-ray should be done, but the clinician should be comfortable with the association if nothing is found.

An epithelioid granuloma is a complex of transformed macrophages together with inflammatory cells and often multinucleated giant cells. It is a manifestation of delayed hypersensitivity.

This is a very good retrospective examination of characteristics associated with hepatogranulomas, with the added strength of the prospective surveillance.

| 1. | Guckian JC, Perry JE. Granulomatous hepatitis. An analysis of 63 cases and review of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 1966;65:1081-1100. |

| 2. | Klatskin G. Hepatic granulomata: problems in interpretation. Mt Sinai J Med. 1977;44:798-812. |

| 3. | Cunnigham D, Mills PR, Quigley EM, Patrick RS, Watkinson G, MacKenzie JF, Russell RI. Hepatic granulomas: experience over a 10-year period in the West of Scotland. Q J Med. 1982;51:162-170. |

| 4. | Goldin RD, Levine TS, Foster GR, Thomas HC. Granulomas and hepatitis C. Histopathology. 1996;28:265-267. |

| 5. | Gaya DR, Thorburn D, Oien KA, Morris AJ, Stanley AJ. Hepatic granulomas: a 10 year single centre experience. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:850-853. |

| 6. | Yamamoto S, Iguchi Y, Ohomoto K, Mitsui Y, Shimabara M, Mikami Y. Epitheloid granuloma formation in type C chronic hepatitis: report of two cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:291-293. |

| 7. | Ozaras R, Tahan V, Mert A, Uraz S, Kanat M, Tabak F, Avsar E, Ozbay G, Celikel CA, Tozun N. The prevalence of hepatic granulomas in chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:449-452. |

| 8. | Mert A, Tabak F, Ozaras R, Tahan V, Senturk H, Ozbay G. Hepatic granulomas in chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:342-343. |

| 9. | Emile JF, Sebagh M, Feray C, David F, Reynes M. The presence of epithelioid granulomas in hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:1095-1097. |

| 10. | Snyder N, Gajula L, Xiao SY, Grady J, Luxon B, Lau DT, Soloway R, Petersen J. APRI: an easy and validated predictor of hepatic fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:535-542. |

| 11. | Snyder N, Nguyen A, Gajula L, Soloway R, Xiao SY, Lau DT, Petersen J. The APRI may be enhanced by the use of the FIBROSpect II in the estimation of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;381:119-123. |

| 12. | Ishak KG. Light microscopic morphology of viral hepatitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;65:787-827. |

| 13. | National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Management of hepatitis C: 2002--June 10-12, 2002. Hepatology. 2002;36:S3-S20. |

| 14. | Batts KP, Ludwig J. Chronic hepatitis. An update on terminology and reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1409-1417. |

| 15. | Ryan BM, McDonald GS, Pilkington R, Kelleher D. The development of hepatic granulomas following interferon-alpha2b therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:349-351. |

| 16. | Gitlin N. Manifestation of sarcoidosis during interferon and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C: a report of two cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:883-885. |

| 17. | Butnor KJ. Pulmonary sarcoidosis induced by interferon-alpha therapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:976-979. |

| 18. | Ubina-Aznar E, Fernandez-Moreno N, Rivera-Irigoin R, Navarro-Jarabo JM, Garcia-Fernandez G, Perez-Aisa A, Vera-Rivero F, Fernandez-Perez F, Moreno-Mejias P, Mendez-Sanchez I. [Pulmonary sarcoidosis associated with pegylated interferon in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;28:450-452. |

| 19. | Menon Y, Cucurull E, Reisin E, Espinoza LR. Interferon-alpha-associated sarcoidosis responsive to infliximab therapy. Am J Med Sci. 2004;328:173-175. |

| 20. | Alfageme Michavila I, Merino Sanchez M, Perez Ronchel J, Lara Lara I, Suarez Garcia E, Lopez Garrido J. [Sarcoidosis following combined ribavirin and interferon therapy: a case report and review of the literature]. Arch Bronconeumol. 2004;40:45-49. |

| 21. | Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:705-714. |

Peer reviewer: Paul J Rowan, PhD, Professor, Department of Management, Policy, and Community Health, Univ of Texas School of Public Health, 1200 Pressler St., RAS E331, Houston 77379, United States

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Ma WH