INTRODUCTION

Capillaria species, being round worm, are members of the superfamily Trichinelloidae. Only three major genera of this group cause human diseases: Trichuris, Trichinella and Capillaria. These worms have an esophagus which is surrounded by glandular cells or stichocytes. This esophageal pattern is called stichosomal esophagus. Capillaria species are parasites in many vertebrate animals but only three species infect humans; Capillaria hepatica, C. aerophila and C. philippinensis[1]. C. philippinensis which causes intestinal capillariasis is the most important and found to infect the human more than other species.

In 1964, the first case of C. philippinensis infection was found in the autopsy of a 29-year-old man from Ilocos Norte province, Northern Luzon, the Philippines, who died from intractable diarrhea[2]. After that, between 1965 and 1967, this disease spread to Pudoc West village, which is approximately 150 kilometers south of the first case. More than 1000 capillariasis cases were found and 77 died of this disease. Lately, Cross reported of the total number of intestinal capillariasis cases in Northern Luzon from 1967 to 1990 to be 1884 cases and 110 deaths[3]. In addition, sporadic cases had been reported from Japan[4], Korea[5], Taiwan, China[6–8], Indonesia[9], Iran[10] and Egypt[11–14]. C. philippinensis causes intermittent or continuous diarrhea leading to weight loss, abdominal pain, borborygmi, muscle wasting, weakness and edema. If the intestinal capillariasis patients are not treated, they will have severe muscle wasting, cachexia, edema and death. Most patients died from electrolyte loss resulting in heart failure and/or septicemia[3].

The earliest case of C. philippinensis in Thailand was reported in 1973 from an 18-mo old Thai girl[15]. Since then sporadic cases had been recorded in other parts of Thailand. In 1981, the first epidemic of intestinal capillariasis was found in Srisaket province in Northeastern part of Thailand, there had been 20 cases and 9 deaths from the disease[16]. However, even when the numbers of the intestinal capillariasis cases in Thailand are reduced, the C. philippinensis infection cases are still reported. Moreover, it probably contributes significantly to morbidity in humans. Therefore, the epidemiology, history and sources of C. philippinensis infection in Thailand, have been reviewed in this paper.

HISTORICAL REVIEW OF INTESTINAL CAPILLARIASIS IN THAILAND

The first record of intestinal capillariasis in Thailand was in 1973. The patient was an 18-mo old Thai girl from Bangpree District of Samut Prakan province. She had diarrhea 2 or 3 times per day, for at least 6 months and edema was found for 3 d. Laboratory examination showed low albumin and potassium in blood. The feces examination revealed eggs, larvae and adults of C. philippinensis in her stool[15]. In 1974, Saraburi Provincial hospital reported the second case of C. philippinensis infection. The 46-year old man who had watery diarrhea 4-5 times a day was admitted to hospital. The result of his blood chemistry and stool examination were similar to the first case. His feces showed a large number of eggs and adults of C. philippinensis[17]. After the two first cases, intestinal capillariasis cases were found in other provinces in Thailand; Nakorn Panom, Surin[18], Phetchabun[19] and Maha Sarakham[20]. All patients presented edema, weight loss and had a history of watery diarrhea 3 to 6 times a day. The low level of albumin and potassium in blood were found and their feces had all stages of Capillaria worm. Most of them lived in raw fish eating regions and some of the cases consumed raw fresh water fish such as Koi Pla, chopped raw fish mixed with lemon juice, finely cut red onion and chili.

The first outbreak of intestinal capillariasis in Thailand was in 1981 from a small village, Phrai Bueng district, Sisaket province. This outbreak had 20 patients and 9 deaths. Most of the cases were adults who were over 20 years of age and 80% of them habited in the same household. The authors believed that man to man transmission may be a possibility because each of the cases was sequent diarrhea[16]. In 1983, Kunaratanapruk et al reported that 100 cases of C. philippinensis infection in hospital had occurred from 1979 to 1981. There were 15 cases that died from intestinal capillariasis. Seventy three percents of the patients were aged in a range between 20 and 49 years and males were more commonly infected than females, about 2.3 times[21].

After the first epidemic in 1981, a number of cases in other parts of Thailand were reported. For example, three intestinal capillariasis patients who lived in the Northeastern part of Thailand were diagnosed by Bamrasnaradura hospital[22]. Seventeen chronic diarrhea patients with C. philippinensis were diagnosed at Srinagarind hospital, Khon Kaen University, from 1983 to 1991. Hypoalbuminemia and ova of C. philippinensis in feces were found in all those cases[23]. Two intestinal capillariasis patients from the North; Phayao and Chaing Mai who had chronic watery diarrhea were admitted to the Maharaj Nakorn Chaing Mai hospital. Both patients showed eggs of C. philippinensis in feces and they were very fond of raw fish food[24]. The latest report, a 27-year-old man who had a history of chronic watery diarrhea for two years was found to contain C. philippinensis ova and worms in his jejunum[25].

LIFE CYCLE

The life cycle of C. philippinensis was proposed by Cross in 1992[3]. From his experimental study, larvae of C. philippinensis from the digestive tract of a freshwater fish (Hypselotris bipartita) in the endemic area were given by stomach tube to Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus). Ten to eleven days post infection; larvae developed to adult stage and female worms generated larvae in 13 to 14 d. After that, these capillaries larvae developed to adults which could release unembryonated eggs within 22-24 d. Moreover, this experiment proposed that autoinfection was found in gerbils. Because they fed only two larvae from fish to gerbils but 852 to 5353 worms were recovered[26].

The biological aspect of fish as the intermediate host of C. philippinensis was reported by several studies. In a study in Thailand, Cyprinus carpio (Pla Nai), Puntius gonionotus (Pla Tapien Khao) and Rasbora boraperensis (Pla Sew), which always are prepared to Koi Pla, were fed C. philippinensis eggs by self feeding or forced feeding. After 10-30 d the results showed the larvae of C. philippinensis were recovered from fish intestines and could develop to egg producing adult in gerbils after feeding them by those larvae[27]. Likewise, Cross et al reported Elotris melanosoma (birut), Ambassis commersoni (bagsang) and Apagon sp. (bagsit), which are fresh water fish in the Philippines, were found to be intermediate hosts in experimental infection. C. philippinensis larvae were recovered from the digestive tract of those fresh water fish and led to intestinal capillariasis after being fed to monkeys[28]. Moreover, two specimens of Apagon sp. were found naturally infected with C. philippinensis larvae but how C. philippinensis can naturally infect fish is not known. The authors suggest that defecation from humans to a water resource in the endemic area is an excellent opportunity for C. philippinensis eggs to contact and be ingested by naturally susceptible fish[28].

Bhaibulaya et al reported fish-eating birds (Amaurornis phoenicurus and Ardeola bacchus) were susceptible to C. philippinensis infection; adults and larvae were recovered from birds’ intestinal content[29]. Similarly, Cross and Basaca-Sevilla revealed C. philippinensis larvae from fish and experimentally infected gerbils could develop to adult males, oviparous and larviparous females in several species of fish-eating birds from Taiwan (Nycticorax nycticorax, Bubulcus ibis, Ixobrychus sinensis, Gallinula chloropus, A. phoenicurus and Rostratula benghalensis) and eggs from those birds hatched and developed to larvae and adults in fish intestines[30]. Therefore, fish-eating birds may be a natural reservoir host that upon defecation, C. philippinensis eggs are released to a water resource in the endemic area or eat C. philippinensis infected fish. These mechanisms can maintain a parasite life cycle in nature.

SYMPTOMS AND PATHOLOGY

The intestinal capillariasis patients usually present watery diarrhea weight loss, abdominal pain, borborygmi, muscle wasting, weakness, edema and laboratory examination showed low levels of potassium and albumin in blood[151831] and malabsorption of fats and sugar[323]. Those patterns may result from C. philippinensis secretion of a proteolytic substance or direct penetration of the intestinal wall that causes cellular injury and dysfunction[23]. Several studies showed intestinal pathological findings in C. philippinensis infection which showed atrophied crypts, flattened villi, and leukocyte cell infiltration that were signs of intestinal cell injury[253132]. Therefore, the destruction of the intestinal cell membrane may interrupt nutrient absorption that causes weight loss in intestinal capillariasis patients. Moreover, the intestinal cells’ destruction may lead to fluids, proteins and electrolytes loss because those intestinal cells are dysfunctional and cannot control fluids and electrolytes balance in the body[33] that results in a low level of potassium and albumin in the blood of C. philippinensis infection patients. The edema in patient, due to hypoalbuminemia[31] according to albumin levels, is plasma protein which controls the fluid in blood vessels by maintaining the osmotic pressure. If the osmotic pressure decreases, the plasma fluid in vessels leaks out of the capillaries into the interstitium and leads to edema in intestinal capillariasis patients[34].

DISTRIBUTION AND PREVALENCE OF INTESTINAL CAPILLARIASIS IN THAILAND

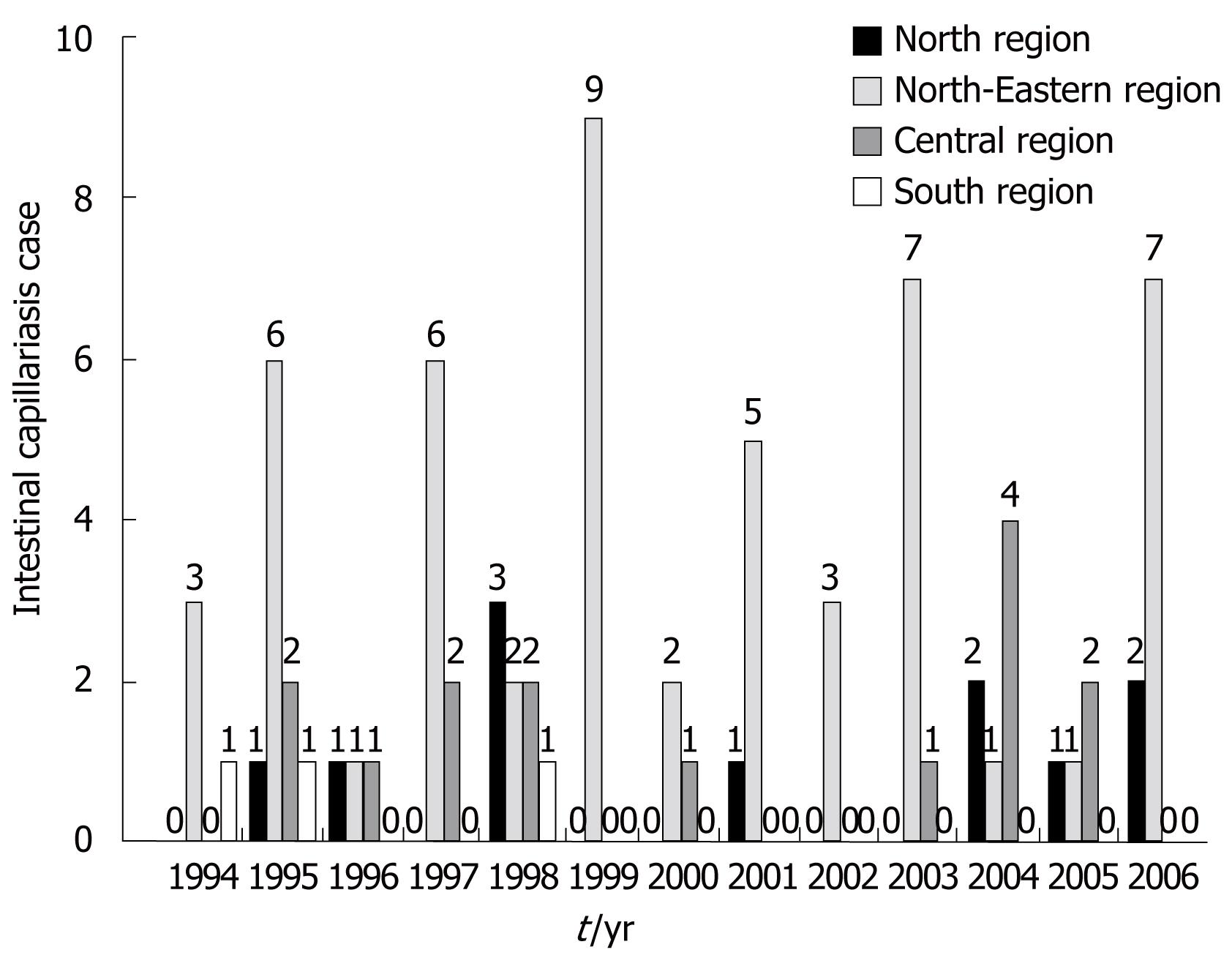

The epidemic of C. philippinensis infection was first recognized from Ah Huad village in a province with an incidence of 20 patients and 9 dead cases[16]. Thereafter, Kunaratanapruk et al recorded intestinal capillariasis cases at hospital. The reports showed 72 cases and 12 died in 1981 and 24 cases and 2 died in 1982[21]. The annual epidemiological surveillance reports indicated that 82 accumulated cases of intestinal capillariasis were found in Thailand from 1994-2006 (Figure 1). Most of the cases occurred in 1995 and only 1 case died from intestinal capillariasis in 1996 (data not show).

Figure 1 Intestinal capillariasis cases in Thailand from 1994 to 2006.

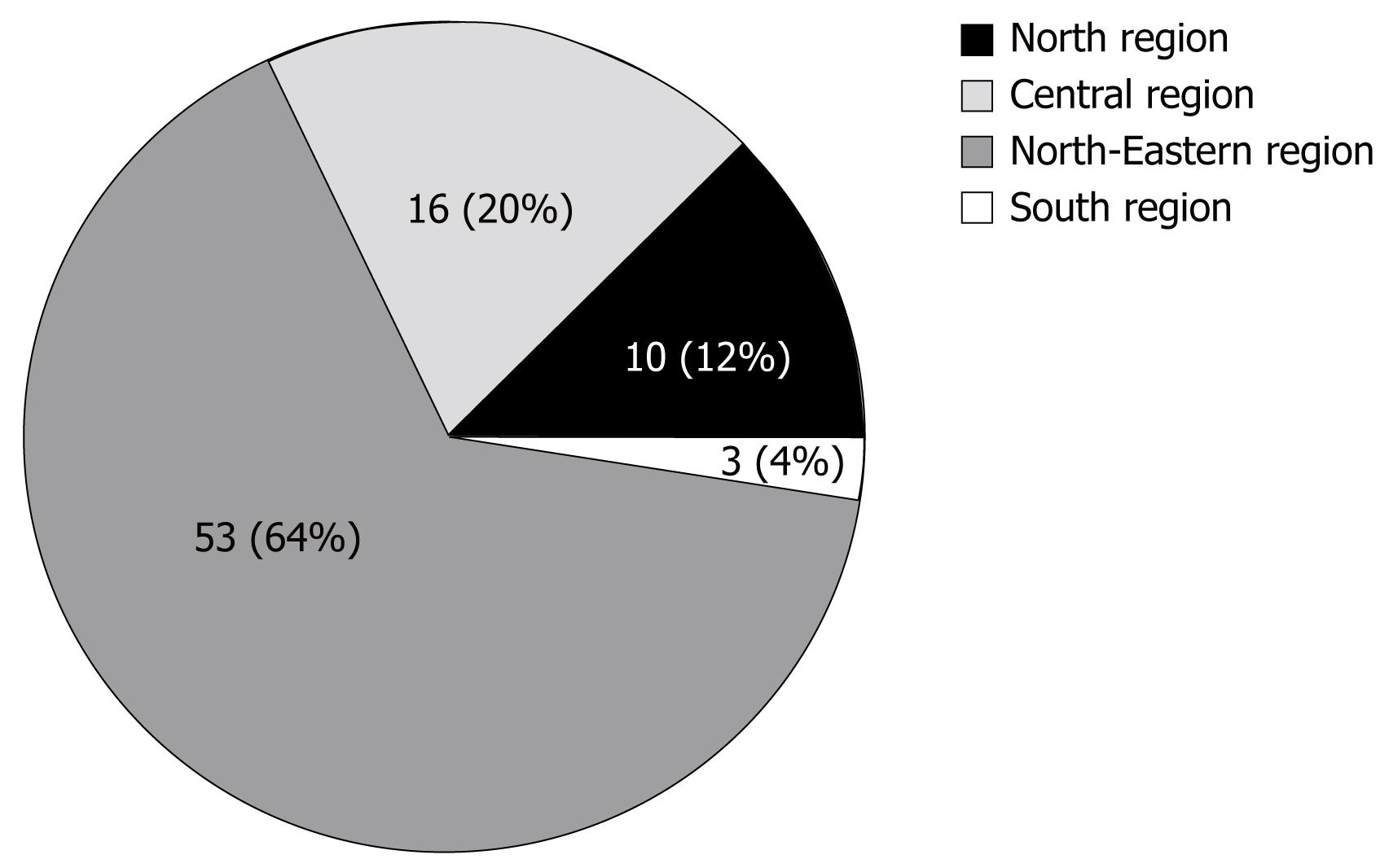

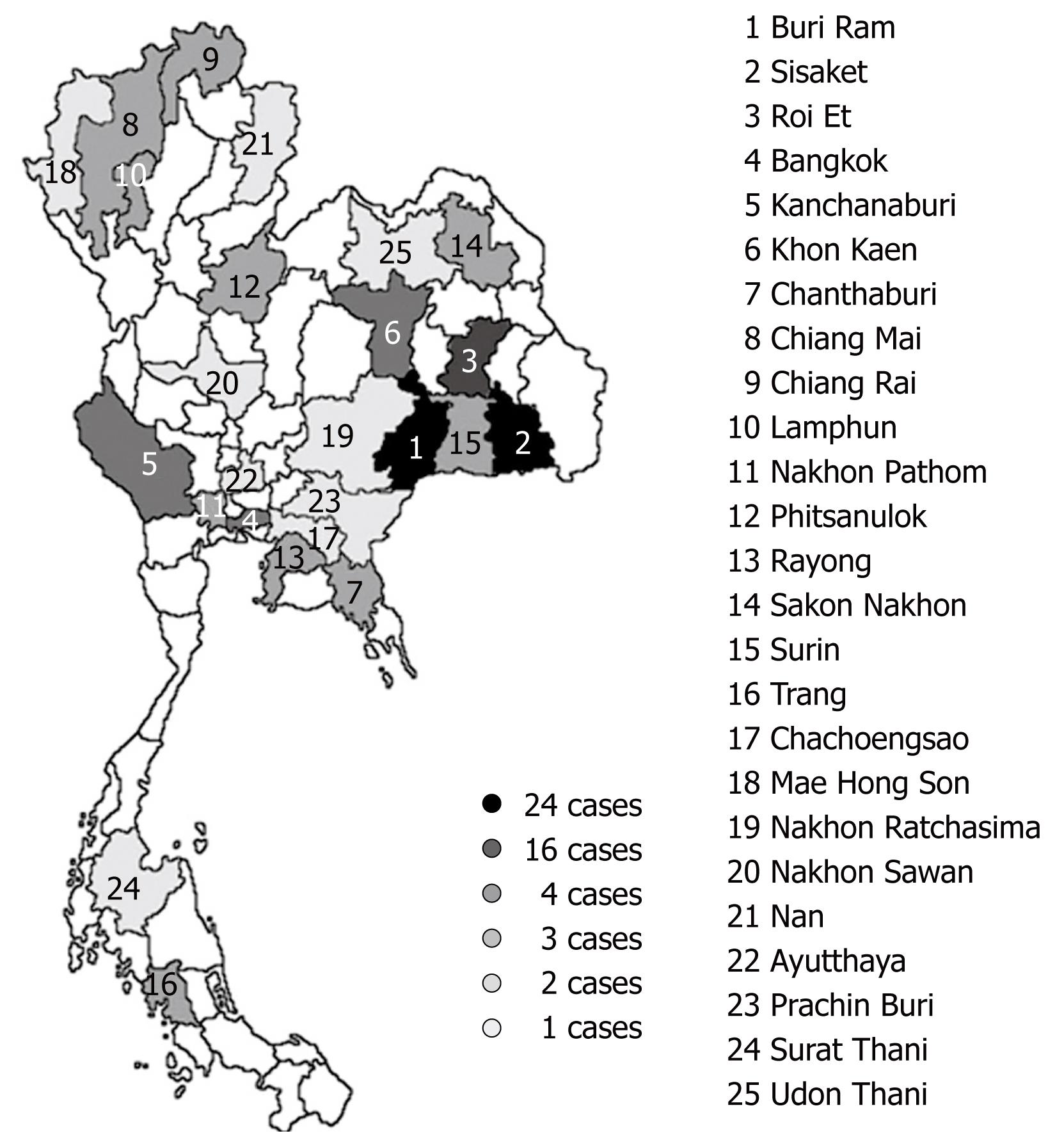

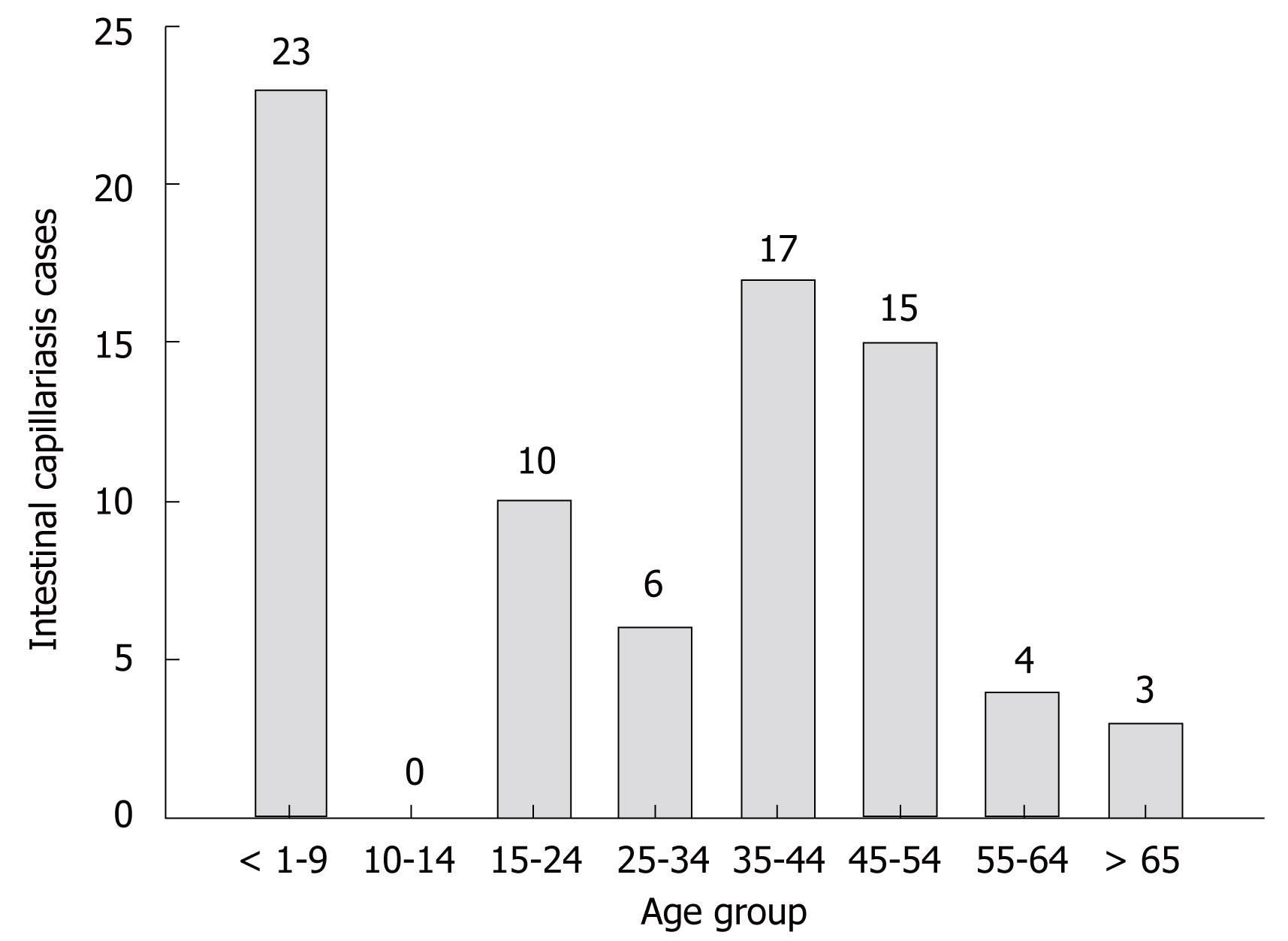

Human intestinal capillariasis has occurred in many parts of Thailand, but is more common in the northeastern area. Owing to the life style, most people in this area like to eat raw fish which is believed to be the source of C. philippinensis infection in the area. Interestingly, no intestinal capillariasis cases were reported from the southern region during 1999 to 2006 (Figure 1). From 1994 to 2006, most of the intestinal capillariasis accumulated cases were found in the northeastern region (53 cases) and the second highest was the central region (16 cases) (Figure 2). This report was similar to previous studies which found most of the intestinal capillariasis cases in the northeastern region[162123]. The provinces in the northeastern region which were found with C. philippinensis infection in 1994 to 2006 were Buri Ram, Khon Kaen, Nakhon Ratchasima, Roi Et, Sakon Nakhon, Surin and Udon Thani (Figure 3). Buri Ram was had the highest reported intestinal capillariasis cases which had 24 cases from 1994-2006. From 1995 through 2006, children ages less than 1 year to 9 years had been mostly infected by C. philippinensis (Figure 4). Contrarily, in the Philippines[3] and Egypt[35] most intestinal capillariasis cases were found in middle-aged or the active age group. This result might be caused by the child playing in the cooking area while their parent prepared food and the child eating small pieces of raw fish similarly reported by El-Dib and Doss[35]. However, working age groups (25-54 years) were still infected by C. philippinensis and had 38 reported cases from 1995-2006 (Figure 4).

Figure 2 Intestinal capillariasis cases (82) reported in Thailand by region from 1994 to 2006.

Figure 3 Twenty-five provinces in Thailand with intestinal capillariasis cases reported from 1994-2006.

Each number in the map represents each province.

Figure 4 Intestinal capillariasis cases in Thailand by age from 1995 to 2006.

DIAGNOSIS OF INTESTINAL CAPILLARIASIS IN THAILAND

The detection of C. philippinensis is based on the recovery of eggs, larvae and/or adult worms in the stool of the patients. Unembryonated C. philippinensis eggs are peanut-shaped with flattened bipolar plugs and a striated shell. Larvae are found in the feces but difficultly identified as C. philippinensis[3]. An inexperienced laboratory worker may confuse with Trichuris trichiura eggs which are prominent mucoid bipolar plugs. The eggs of C. philippinensis are excreted sporadically in feces that lead to delayed diagnoses as intestinal capillariasis. Therefore, multiple stool samples may be important to early diagnosis in some cases[3]. In most of the intestinal capillariasis cases reported in Thailand eggs, larvae or adult worms in feces were found[151618–2022], but there were some patients that died from C. philippinensis infection in whom Capillaria eggs or larvae were not found in the feces[31]. However, small intestinal aspiration or biopsy may be necessary to confirm Capillaria infection[3]. For example, gastroduodenoscopy in a 13-year-old boy from central Thailand showed C. philippinensis eggs in a jejunal biopsy[32]. Moreover, jejunal mucosal biopsy and microscopic jejunal content examinations were successfully used to identify intestinal capillariasis in a 27-year-old Thai man who had negative repeated stool tests[25]. Immunodiagnosis may be a supplementary diagnostic tool which helps to detect C. philippinensis infection. Recently, Intapan et al investigated the intestinal capillaries using Trichinella spiralis antigen[36]. The study revealed sera from intestinal capillariasis patients were positive with T. spiralis antigen. This may be useful for screening of persons who have intestinal capillariasis-like symptoms before discovering Capillaria eggs or larvae in their stool[36].

SOURCE OF INTESTINAL CAPILLARIASIS IN THAILAND

C. philippinensis infection is mostly found in raw fish eating areas. For example, the people in Ilocos Norte province, in the Philippines, like to eat raw bagsit (Hypseleotris bipartita), Capillaria larvae containing fish, in a single bite leads to infection by C. philippinensis[3]. Similarly in Thailand, Koi pla and Taab Kaab are common foods that cause infection with intestinal capillariasis. Koi pla is made from chopped raw fish mixed with lemon juice, finely cut red onion and chili. Taab Kaab is made from pounded raw whole fish mixed with lemon juice, finely cut red onion and chili. These foods are favorite dishes in agricultural areas because they are easy to prepare and fresh water fish are found plentiful chiefly in these regions. In experimental study, fresh water fish in Thailand such as C. carpio (Pla Nai), P. gonionotus (Pla Tapien Khao) and R. boraperensis (Pla Sew), which are used to prepare Koi pla and Taab Kaab, could serve as experimental intermediate hosts for C. philippinensis[27]. Moreover, some people usually chew the fish freshly caught because those fish are too small to eviscerate. So the raw fresh water fish eating behavior is a major factor associated with intestinal capillariasis in Thailand.

STRATEGY FOR INTESTINAL CAPILLARIASIS CONTROL

Intestinal capillariasis is a severe disease that may lead to death unless patients are treated. The symptoms of C. philippinensis infection are continuous or intermittent watery diarrhea associated with severe weight loss, severe protein-loss and severe electrolyte depletion. These lead patients to die from intestinal capillariasis, so the strategy to fight the disease consists of not eating raw fish, promoting a health education program and early diagnosis are necessary to minimize or eradicate C. philippinensis infection in Thailand.

The health education campaign aims to promote the consumption of cooked fish and to avoid defecation into a water resource in order to eliminate C. philippinensis infection. The early diagnosis is necessary for treating intestinal capillariasis patients, especially improving the experience of laboratory workers and multiple stool examination must be required.

Peer reviewer: Hitoshi Asakura, Director, Emeritus Professor, International Medical Information Center, Shinanomachi Renga Bldg.35, Shinanomachi, Shinjukuku, Tokyo 160-0016, Japan