Published online Oct 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6078

Revised: September 16, 2008

Accepted: September 23, 2008

Published online: October 21, 2008

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-guided biliary drainage was performed for treatment of patients who have obstructive jaundice in cases of failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). In the present study, we introduced the feasibility and outcome of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy in four patients who failed in ERCP. We performed the procedure in 2 papilla of Vater, including one resectable case, and 2 cases of cancer of the head of pancreas. Using a curved linear array echoendoscope, a 19 G needle or a needle knife was punctured transduodenally into the bile duct under EUS visualization. Using a biliary catheter for dilation, or papillary balloon dilator, a 7-Fr plastic stent was inserted through the choledochoduodenostomy site into the extrahepatic bile duct. In 3 (75%) of 4 cases, an indwelling plastic stent was placed, and in one case in which the stent could not be advanced into the bile duct, a naso-biliary drainage tube was placed instead. In all cases, the obstructive jaundice rapidly improved after the procedure. Focal peritonitis and bleeding not requiring blood transfusion was seen in one case. In this case, pancreatoduodenectomy was performed and the surgical findings revealed severe adhesion around the choledochoduodenostomy site. Although further studies and development of devices are mandatory, EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy appears to be an effective alternative to ERCP in selected cases.

- Citation: Itoi T, Itokawa F, Sofuni A, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Moriyasu F. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy in patients with failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(39): 6078-6082

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i39/6078.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6078

Endoscopic transpapillary biliary stenting is the most common procedure for biliary drainage in patients with obstructive jaundice. However, there are patients who failed to achieve bile duct access because of failed biliary cannulation or an inaccessible papilla due to severe duodenal stenosis caused by tumor invasion. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or surgical intervention is required in such cases. Both methods have a higher morbidity and mortality than endoscopic methods[1-5]. Recently, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-guided choledochoduodenostomy has been reported as an alternative biliary drainage technique[6-10]. The aim of the study is to evaluate the potential role of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy in the biliary drainage.

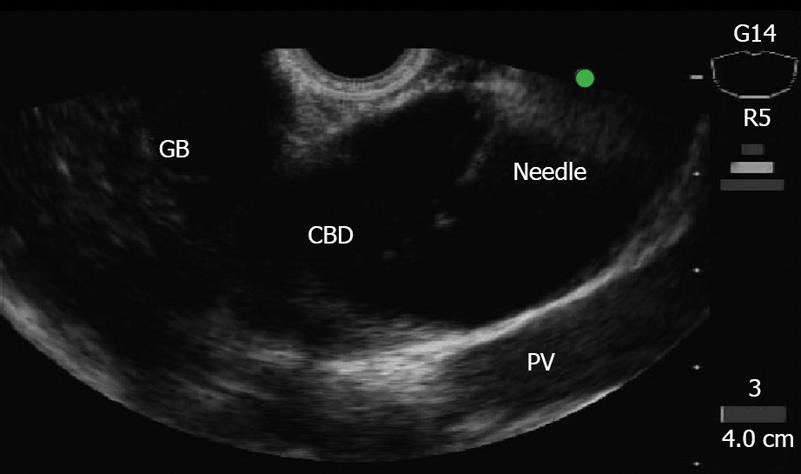

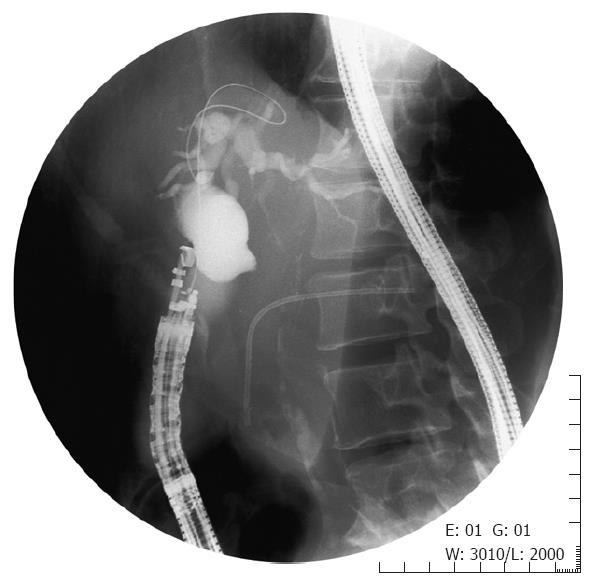

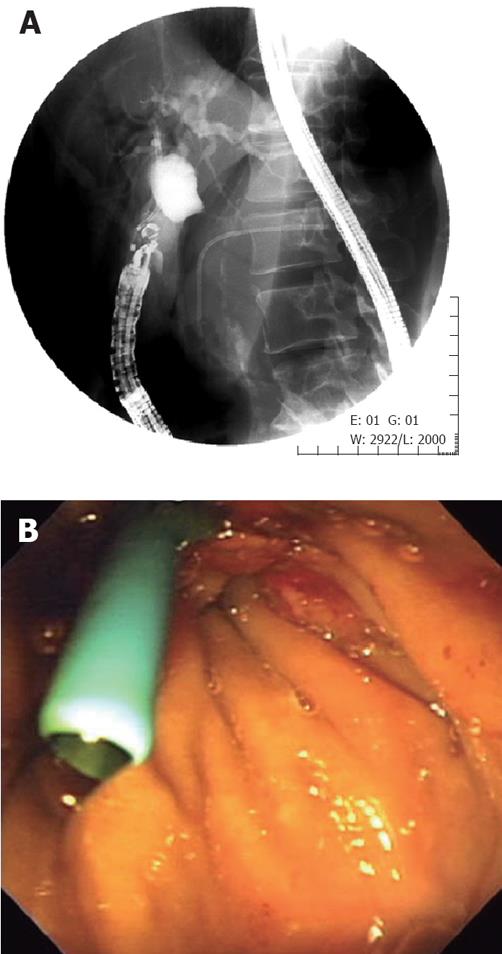

This series includes all procedures performed at our institution between June 2005 and January 2008. At first, we attempted endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) in all patients. If standard ERCP techniques failed, precut sphincterotomy was used for biliary cannulation. The EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy was performed only in case of failed biliary cannulation or inaccessible papilla due to severe duodenal stenosis caused by tumor invasion. Using an echoendoscope with a curved linear array transducer, and a 3.7-mm accessory channel with an elevator (GF-UCT2000-OL5, Olympus Medical Systems Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), the extrahepatic bile duct was visualized at the level of the duodenal bulb (Figure 1). A 19-gauge needle (EchoTip, Wilson-Cook, Winston-Salem, NC) without electrocoagulation, or a needle knife (Zimmon papillotomy knife, Wilson-Cook) with electrocoagulation (EndoCut ICC200, ERBE ELEKTROMEDIZIN GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) was inserted transduodenally into the bile duct under EUS visualization. After the central needle is removed, bile is aspirated and contrast medium is injected into the bile duct for cholangiography, and 450 cm long, a 0.035-inch guide wire is inserted into the outer sheath (Figure 2). If necessary, a biliary catheter for dilation, or papillary balloon dilator is used for dilation of duodenocholedochostomy site. Finally, a 7-Fr biliary plastic stent (FLEXIMA, Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted through the choledochoduodenostomy site into the extrahepatic bile duct (Figure 3).

After written informed consent was obtained from patients, all endoscopic procedures were performed with the patients under conscious sedation with intravenous flunitrazepam (5-10 mg). As for antibiotics, 1 g cefotiam hydrochloride was administered by intravenous drip infusion once on the test day and twice on the following day. This study was approved by the institutional review board of our institution.

An 80-year-old man was admitted for treatment of obstructive jaundice. Tumor invasion to the duodenal wall at the circumference of the major papilla was detected when the procedure was impossible. Biopsy specimens from the major duodenal papilla revealed adenocarcinoma of the papilla of Vater. Using a Zimmon needle knife, EUS-guide choledochoduodenostomy was performed. After dilation by a Soehendra dilator catheter (SBDC-7 and SBDC-9, Wilson-Cook), an indwelling 7-Fr plastic stent was placed across the choledochoduodenostomy site into the extrahepatic bile duct without any complications. The obstructive jaundice rapidly improved after insertion of the biliary stent. The stent did not occlude, and the patient died of pneumonia 3 mo after the procedure.

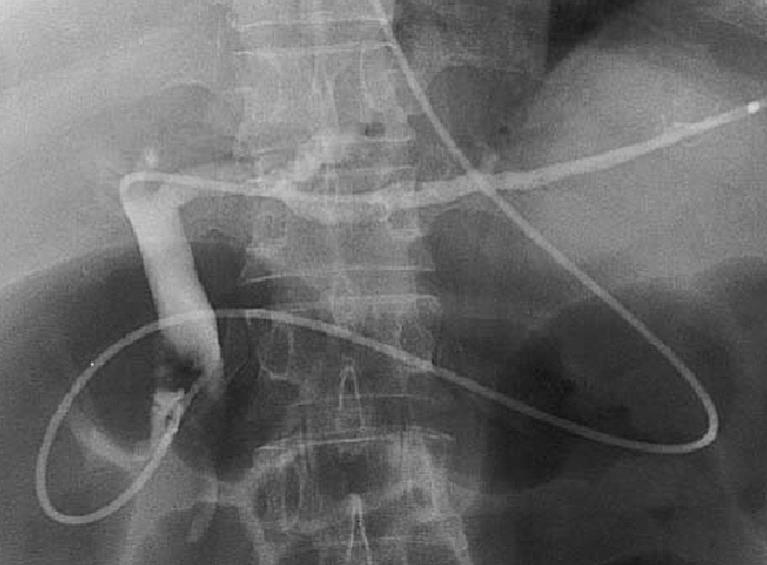

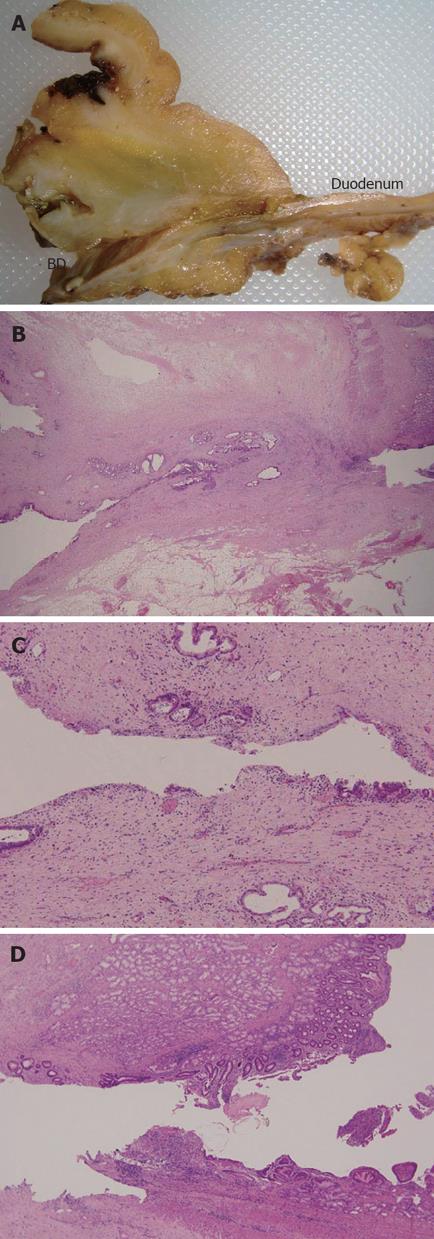

A 71-year-old man admitted for abdominal pain and obstructive jaundice. Computer tomography (CT) showed a huge papilla of Vater tumor with a dilated bile duct and mild pancreatitis. Biopsy specimens from the major duodenal papilla revealed adenocarcinoma of the papilla of Vater. Imaging revealed that the tumor was resectable. However, since the biliary cannulation for biliary decompression was impossible because the tumor occupied the duodenal lumen, EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy was performed. After puncture using a Zimmon needle knife, dilation of the choledochoduodenostomy site by a Soehendra dilator catheter was performed. Subsequently, we attempted to insert a 7-Fr plastic stent from the first portion of duodenum into the extrahepatic bile duct, but stent insertion was impossible because the tip of the stent became impacted in the bile duct site of choledochoduodenostomy. Although balloon dilation was performed across the choledochoduodenostomy site, a 7-Fr stent could not be inserted, therefore, a 5-Fr naso-biliary drainage tube was inserted into the left intrahepatic bile duct (Figure 4). Although the obstructive jaundice rapidly improved after the procedure, there was bleeding not requiring blood transfusion and smoldering focal peritonitis of choledochoduodenostomy site. No evidence of intra-abdominal bile leak was found by several cholangiography procedures via the naso-biliary drainage tube. Pancreatoduodenectomy 16 d after the procedure revealed severe adhesion around the choledochoduodenostomy site although choledochoduodenostomy was completed (Figure 5A). Histological examination revealed mild inflammatory cell infiltrate adjacent to the sinus tract in the duodenal and bile duct walls (Figure 5B-D). The patient is presently healthy 13 mo after surgery.

A 69-year-old man with a history of chronic pancreatitis and placement of pancreatic stent for the treatment of abdominal pain, was admitted with obstructive jaundice. ERCP was impossible because the duodenoscope could not pass through a severe stricture. EUS-FNA specimens from pancreas mass showed adenocarcinoma. Using a 19-gauge needle (EchoTip, Wilson-Cook), EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy was performed. After dilation by a Soehendra dilator catheter, a 7-Fr plastic stent was placed into the extrahepatic bile duct without any complications. The obstructive jaundice rapidly improved after insertion of the biliary stent. Since acute cholangitis occurred 2 wk after the procedure due to stent clogging, we replaced the plastic stent by a self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) using a guide wire plus snare forceps technique because the choledochoduodenal fistula seemed to be incomplete. Actually, after placement of the first 10-Fr uncovered SEMS (Niti-S, Teung Medical Co. Ltd. Seoul, Korea), contrast medium flowed out of the bile duct to the intra-abdominal space. A second 10-Fr covered SEMS (Combi-S, Teung Medical Co. Ltd.), therefore, was placed in the first SEMS. No complications occurred and the patient had no symptoms 3 mo later at follow-up.

An 86-year-old woman with unresectable cancer of the head of the pancreas who had undergone biliary stenting 1 mo previously, was admitted with obstructive jaundice. At initial ERCP, an indwelling 10-Fr plastic stent (FLEXIMA, Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was placed. ERCP was impossible because the duodenoscope could not pass through the tight stricture caused by cancer invasion. Then, EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy was performed. Using a 19-gauge needle (EchoTip, Wilson-Cook), EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy was performed. After dilation by a Soehendra dilator catheter, a 7-Fr plastic stent was placed into the extrahepatic bile duct without any complications. The obstructive jaundice rapidly improved after insertion of the biliary stent. No complications occurred and the patients had no related symptoms till she died 1 mo later.

Endoscopic biliary stent placement is the most well-established method for the treatment of obstructive jaundice[11]. When ERCP fails, usually, PTBD is chosen as an alternative method for treating biliary decompression[12]. Recently, EUS-guided biliary drainage using either direct access or a rendezvous technique, has attracted attention as an alternative procedure to ERCP or PTCS[6-10,13-17]. Until now, of these EUS-guided biliary drainage procedures, EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy has been performed in 17 cases consisting of 11 pancreatic cancer, 4 papilla of Vater cancer, 1 bile duct cancer, and 1 bile duct stone[6-10].

The methodology and devices of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy are not yet fully established. Therefore, there are several important factors during the procedure to ensure technical success. First, as Yamao et al[9] mentioned, the scope position and puncture site are very important. Theoretically, the scope pushing position at which the tip of the convex transducer is directed at the hepatic hilum, is promising because the access route to the bile duct is shorter from the duodenal bulb to the bile duct and the echoendoscope is stable when several devices are advanced into the bile duct through the working channel[9]. However, when there is duodenal stenosis due to tumor invasion, anatomically abnormal situation after surgery, the same scope position may not be always possible. Second, the type of puncture needle also may be one of the most important factors. Several reports describe that various types of needle knife are used for puncture in all but two cases (88%, 15/17)[6-10]. Although a needle knife could make a larger hole compared to a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) needle which needs dilators or balloon dilation for the subsequent procedure, a larger hole may lead to possible intra-abdominal bile leak. In the present series, we used both a FNA needle and a needle knife with electrical coagulation. Unfortunately, one case using a needle knife failed in stent insertion despite making a comparatively large hole and also using a dilator and balloon. The main reason for this may be that the tip of the convex transducer was directed not at the hepatic hilum but the distal bile duct. In this case, the direction of the guidewire was changed from distal bile duct to hepatic hilum to enable technical success. Therefore, it may be possible that the choledochoduodenostomy site became kinked and the stent could not torque adequately because of the instabilization of the scope. These data suggest that technical success of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy may depend not on the choice of needle, but mainly the scope position and direction of puncture.

Several investigators used various diameter plastic stents[6,7,9,10,18] or a SEMS[8]. Although the stent diameter depends on the echoendoscope used, large bore plastic stent may be better for long patency, similar to the conventional transpapillary plastic stent. Recently, Yamao et al[19] has reported that the mean stent patency of 7- 8.5-Fr plastic stents for EUS-guided chodedocho-duodenostomy was 211.8 d. Since there are few data on SEMS in this procedure, the usefulness of SEMS should be evaluated from the aspect of cost effectiveness including the issue of the use of uncovered or covered SEMS.

Previous data revealed that the procedure was successful in all but 2 cases (a total success rate of 88%) and once stents were placed, all patients had successful resolution of biliary decompression. In the present study, in all patients, the obstructive jaundice rapidly improved after insertion of the biliary stent. These data suggest that this procedure may be as effective as conventional transpapillary biliary drainage once the indwelling stent is placed.

Surprisingly, no serious procedure-related complications were found in several reports although there was 1 case of mild focal bile peritonitis and 3 of pneumoperitoneum[6-10]. In the current study, we encountered 1 focal peritonitis with bleeding without severe complications. However, we must be cautious in evaluating the safety of the procedure because previous published data may be biased towards successful cases.

In conclusion, we report four cases of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for the treatment of obstructive jaundice. This procedure was performed successfully, without severe complications and with highly effective biliary drainage. Although further studies and development of devices are necessary, EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy can be an effective alternative to ERCP.

Peer reviewer: Hsiu-Po Wang, Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, No 7, Chung-Shan South Rd, Taipei 10016, Taiwan, China

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Yin DH

| 1. | Guenther RW, Vorwerk DR. Perkutane Gallenwegsdrainage. Interventionelle radiology. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme 1996; 472-481. |

| 2. | Richter A, Brambs HJ. Interventionen an Gallengängen. Interventionelle minimal invasive Radiologie. 1st ed. New York: Thieme 2001; 58-64. |

| 3. | Smith AC, Dowsett JF, Russell RC, Hatfield AR, Cotton PB. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bileduct obstruction. Lancet. 1994;344:1655-1660. |

| 4. | Lai EC, Mok FP, Tan ES, Lo CM, Fan ST, You KT, Wong J. Endoscopic biliary drainage for severe acute cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1582-1586. |

| 5. | Pessa ME, Hawkins IF, Vogel SB. The treatment of acute cholangitis. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage before definitive therapy. Ann Surg. 1987;205:389-392. |

| 6. | Giovannini M, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, Bories E, Lelong B, Delpero JR. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided bilioduodenal anastomosis: a new technique for biliary drainage. Endoscopy. 2001;33:898-900. |

| 7. | Burmester E, Niehaus J, Leineweber T, Huetteroth T. EUS-cholangio-drainage of the bile duct: report of 4 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:246-251. |

| 8. | Kahaleh M, Hernandez AJ, Tokar J, Adams RB, Shami VM, Yeaton P. Interventional EUS-guided cholangiography: evaluation of a technique in evolution. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:52-59. |

| 9. | Yamao K, Sawaki A, Takahashi K, Imaoka H, Ashida R, Mizuno N. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for palliative biliary drainage in case of papillary obstruction: report of 2 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:663-667. |

| 10. | Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Ito K, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Nakahara K. Histological changes at an endosonography-guided biliary drainage site: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5512-5515. |

| 11. | Soehendra N, Reynders-Frederix V. Palliative bile duct drainage-a new endoscopic method of introducing a transpapillary drain. Endoscopy. 1980;12:8-11. |

| 12. | Takada T, Hanyu F, Kobayashi S, Uchida Y. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage: direct approach under fluoroscopic control. J Surg Oncol. 1976;8:83-97. |

| 13. | Giovannini M, Dotti M, Bories E, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, Danisi C, Delpero JR. Hepaticogastrostomy by echo-endoscopy as a palliative treatment in a patient with metastatic biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2003;35:1076-1078. |

| 14. | Mallery S, Matlock J, Freeman ML. EUS-guided rendezvous drainage of obstructed biliary and pancreatic ducts: Report of 6 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:100-107. |

| 15. | Kahaleh M, Yoshida C, Kane L, Yeaton P. Interventional EUS cholangiography: A report of five cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:138-142. |

| 16. | Bories E, Pesenti C, Caillol F, Lopes C, Giovannini M. Transgastric endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage: results of a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:287-291. |

| 17. | Will U, Thieme A, Fueldner F, Gerlach R, Wanzar I, Meyer F. Treatment of biliary obstruction in selected patients by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-guided transluminal biliary drainage. Endoscopy. 2007;39:292-295. |

| 18. | Puspok A, Lomoschitz F, Dejaco C, Hejna M, Sautner T, Gangl A. Endoscopic ultrasound guided therapy of benign and malignant biliary obstruction: a case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1743-1747. |