Published online Sep 28, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5595

Revised: August 18, 2008

Accepted: August 25, 2008

Published online: September 28, 2008

AIM: To investigate the frequency and risk factors for acute pancreatitis after pancreatic guidewire placement (P-GW) in achieving cannulation of the bile duct during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP).

METHODS: P-GW was performed in 113 patients in whom cannulation of the bile duct was difficult. The success rate of biliary cannulation, the frequency and risk factors of post-ERCP pancreatitis, and the frequency of spontaneous migration of the pancreatic duct stent were investigated.

RESULTS: Selective biliary cannulation with P-GW was achieved in 73% of the patients. Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in 12% (14 patients: mild, 13; moderate, 1). Prophylactic pancreatic stenting was attempted in 59% of the patients. Of the 64 patients who successfully underwent stent placement, three developed mild pancreatitis (4.7%). Of the 49 patients without stent placement, 11 developed pancreatitis (22%: mild, 10; moderate, 1). Of the five patients in whom stent placement was unsuccessful, two developed mild pancreatitis. Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed no pancreatic stenting to be the only significant risk factor for pancreatitis. Spontaneous migration of the stent was observed within two weeks in 92% of the patients who had undergone pancreatic duct stenting.

CONCLUSION: P-GW is useful for achieving selective biliary cannulation. Pancreatic duct stenting after P-GW can reduce the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis, which requires evaluation by means of prospective randomized controlled trials.

- Citation: Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Koshita S, Kanno Y. Pancreatic guidewire placement for achieving selective biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(36): 5595-5600

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i36/5595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.5595

| Characteristics and diagnosis | Number of patients |

| Mean age (range, yr) | 70 (33-90) |

| Male/Female | 63/50 |

| History of pancreatitis | 8 (7%) |

| History of post-ERCP pancreatitis | 0% |

| Normal bilirubin level | 67 (59%) |

| Duodenal diverticulum | 32 (28%) |

| Pancreatic duct stenosis | 7 (6%) |

| Mean procedure time (range, min) | 46 (17-98) |

| Procedure time > 45 min | 52 (46%) |

| Therapeutic ERCP | 75 (66%) |

| Pancreatic duct opacification | 100 (100%) |

| Pancreatic duct stenting | 64 (57%) |

| Biliary sphincterotomy | 39 (35%) |

| Precut | 8 (7.1%) |

| Intraductal ultrasonography | 25 (22%) |

| Biliary stent placement | 24 (21%) |

| Papillary balloon dilatation | 2 (1.8%) |

| Cytology of bile/pancreatic juice | 11 (9.7%) |

| Biopsy of the bile duct/pancreatic duct | 10 (8.8%) |

| Choledocholithiasis | 42 (37%) |

| Cholecystolithiasis | 26 (23%) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 9 (8.0%) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 8 (7.1%) |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 5 (4.4%) |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 4 (3.5%) |

| Ampullary cancer/adenoma | 4 (3.5%) |

| Risk factors | Pancreatitis (+) | Pancreatitis (-) | P | OR (95% CI) |

| (n = 14) | (n = 99) | |||

| Age (< 50 yr) | 2 (14) | 3 (3) | 0.22 | 5.3 (0.81-35) |

| Female gender | 8 (57) | 42 (42) | 0.45 | 1.8 (0.58-5.6) |

| History of pancreatitis | 0 | 8 (8) | 0.58 | - |

| Normal bilirubin level | 12 (86) | 55 (56) | 0.063 | 4.8 (1.0-23) |

| Duodenal diverticulum | 3 (21) | 29 (29) | 0.77 | 0.66 (0.17-2.5) |

| Pancreatic duct stenosis | 0 | 7 (7) | 0.66 | - |

| Procedure time > 45 min | 5 (36) | 47 (47) | 0.59 | 0.61 (0.19-2.0) |

| Therapeutic ERCP | 7 (50) | 68 (69) | 0.28 | 0.46 (0.15-1.4) |

| PD opacification | 14 (100) | 99 (100) | - | - |

| No PD stenting | 11 (79) | 38 (38) | 0.011 | 5.9 (1.5-22) |

| Failure in PD stenting | 2 (14) | 3 (3) | 0.22 | 5.3 (0.81-35) |

| Unsuccessful BD cannulation | 4 (29) | 27 (27) | 0.83 | 1.1 (0.31-3.7) |

| Biliary sphincterotomy | 3 (21) | 36 (36) | 0.42 | 0.48 (0.12-1.8) |

| Precut | 2 (14) | 6 (6) | 0.57 | 2.6 (0.47-14) |

| Intraductal ultrasonography | 3 (21) | 22 (22) | 0.78 | 0.95 (0.24-3.7) |

| Biliary stent placement | 2 (14) | 22 (22) | 0.74 | 0.58 (0.12-2.8) |

| Papillary balloon dilatation | 1 (7) | 1 (1) | 0.58 | 7.5 (0.44-128) |

| Cytology of bile/pancreatic juice | 1 (7) | 10 (10) | 0.89 | 0.68 (0.081-5.8) |

| Biopsy of the BD/PD | 1 (7) | 9 (9) | 0.79 | 0.77 (0.090-6.6) |

| Choledocholithiasis | 5 (36) | 37 (37) | 0.86 | 0.93 (0.29-3.0) |

| Cholecystolithiasis | 5 (36) | 21 (21) | 0.39 | 2.1 (0.62-6.8) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 1 (7) | 8 (8) | 0.68 | 0.88 (0.10-7.6) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 0 | 8 (8) | 0.58 | - |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 0 | 5 (5) | 0.87 | - |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 1 (7) | 3 (3) | 0.99 | 2.5 (0.24-25) |

| Ampullary cancer/adenoma | 0 | 4 (4) | 0.99 | - |

| P | |

| Age (< 50 yr) | 0.9 |

| Female gender | 0.97 |

| Normal bilirubin level | 0.12 |

| Therapeutic ERCP | 0.63 |

| Biliary sphincterotomy | 0.81 |

| No PD stenting | 0.017 |

| Unsuccessful BD cannulation | 0.65 |

| Cholecystolithiasis | 0.44 |

Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP), which was first reported in the late 1960’s[1], is a well-accepted technique for evaluating pancreato-biliary diseases. Although selective cannulation of the bile duct is mandatory for therapeutic ERCP of biliary diseases, anatomical difficulties or papillary spasm sometimes preclude it. Numerous techniques have been developed for selective biliary cannulation[2,3]. Pancreatic guidewire placement (P-GW) has been reported to be effective in patients with difficult cannulation of the bile duct[4-7]. Since P-GW is usually attempted in patients with difficult cannulation of the bile duct, this technique entails a possible increased risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis. The aim of this study was to investigate the frequency and risk factors for acute pancreatitis after P-GW in achieving cannulation of the bile duct during ERCP.

Between December, 2001 and January, 2008, 3955 ERCPs were performed at Sendai City Medical Center. P-GW was performed in patients with pancreato-biliary diseases in whom cannulation of the bile duct was difficult and guidewire insertion into the pancreatic duct was achieved. Difficult cannulation of the bile duct was defined as unsuccessful cannulation with a cannula or a sphincterotome within 15 min. Wire-guided cannulation was not performed in this study. Patients in whom an insertion of a guidewire into the pancreatic duct could not be achieved were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the procedure. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sendai City Medical Center. Prophylactic pancreatic stenting was performed in selected patients after P-GW. Indication for pancreatic duct stenting was determined by each operator during the procedure. Established criteria for pancreatic duct stenting after P-GW was not determined in this study.

Before endoscopic procedures, all patients were given a standard premedication consisting of intravenous administration of pentazocine (7.5-15 mg) and diazepam (3-10 mg) or midazolam (3-10 mg), the doses depending on age and tolerance. The procedures were carried out with side-viewing duodenoscopes (JF200, 230, 240, 260V: Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan). When selective biliary cannulation with a cannula or a sphincterotomy was regarded as difficult, P-GW was attempted. A 0.025-inch or 0.035-inch guidewire (Jagwire: Microvasive, Boston Scientific Corp., Natick, MA, USA) was inserted into the pancreatic duct via the cannula in order to stabilize the papilla of Vater and straighten the bile duct terminal. Alongside the guidewire, a second cannula was passed into the same working channel of the scope with the two-devices-in-one-channel method[8], and cannulation of the bile duct was attempted. After successful cannulation of the bile duct, additional procedures such as endoscopic sphincterotomy, biliary stent placement, intraductal ultrasonography, biopsy of the bile duct, and so on were performed as necessary. Pancreatic duct stenting was performed for prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. The pancreatic duct stent used was a 5 Fr, 4-cm-long stent with a single duodenal pigtail (Pit-stent: Cathex, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). All procedures were performed by operators with experience in more than 500 ERCPs. Abdominal radiographs were obtained to assess the stent position after deployment within 14 d after the ERCP. Endoscopic stent removal was performed if necessary.

Patients continued to fast after the procedure for a minimum of 24 h with drip infusion of 2000 mL and remained in the hospital for at least 48 h. They received 8-h infusion of protease inhibitor (nafamostat mesilate, 20 mg/d) and antibiotics (SBT/CPZ, 2 g/d) for 2 d. Serum amylase levels were measured before the procedure and 3 h, 6 h and 24 h afterwards. The reference range was 42-130 IU/L for the amylase. Symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea, etc.) and physical findings (abdominal tenderness) were clinically evaluated.

The success rate of bile duct cannulation, the frequency and risk factors of post-ERCP pancreatitis, and the frequency of spontaneous migration of the pancreatic duct stent were investigated.

A diagnosis of post-ERCP pancreatitis was made based on the presence of abdominal pain 24 h after the procedure and an increase in serum amylase level greater than three times the upper normal limit[9]. The severity of pancreatitis was classified as mild if prolongation of fasting was within 1-3 d, moderate for fasting 4-10 d long, and severe for fasting more as 10 d, as well as in cases of hemorrhagic pancreatitis, phlegmon, or pseudocyst.

Fisher’s exact probability test was used for statistical analyses where appropriate. Variables found to be possibly significant (P < 0.5) in univariate analysis were chosen for entry into a multiple logistic regression. A P value less than 0.05 was regarded as significant. Statistical analysis was performed with StatMate III (ATMS Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and StatView Ver.5.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

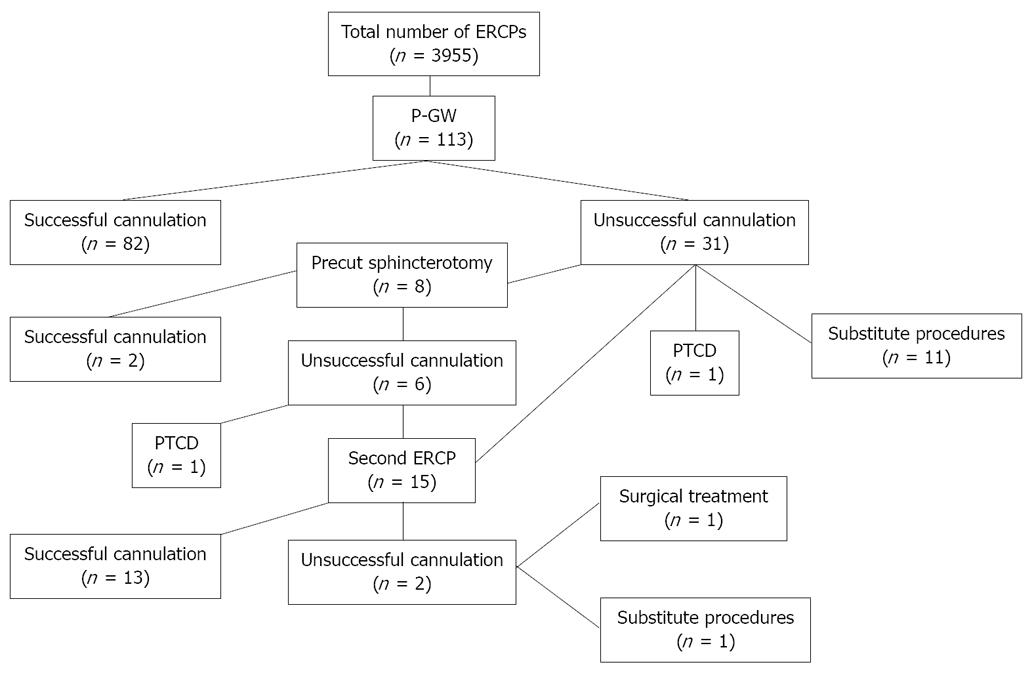

Table 1 shows the characteristics and diagnoses of the patients. Selective biliary cannulation with P-GW was achieved in 73% of the patients (82 patients, Figure 1). Of the remaining 31 patients with unsuccessful biliary cannulation, eight underwent precut sphincterotomy in the same session, biliary cannulation being subsequently achieved in two of them. The other patients underwent a second ERCP including precut sphincterotomy, percutaneous biliary drainage, surgical treatment, or substitute diagnostic procedures. Selective biliary cannulation was finally achieved in 86% of the patients (97 patients).

Prophylactic pancreatic duct stenting was attempted in 59% of the patients (69 patients). Although stenting was successful in all patients, five developed migration of the stent during the procedure.

Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in 12% (14 patients: mild, 13; moderate, 1). All of them improved with conservative therapy in a few days. Of the 64 patients who successfully underwent pancreatic duct stenting, three developed mild pancreatitis (4.7%). Of the remaining 49 patients without a stent, 11 developed pancreatitis (22%: mild, 10; moderate, 1). Of the five patients with stent migration, two developed mild pancreatitis (40%).

Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in 13% of the 31 patients with unsuccessful biliary cannulation. Of the patients with unsuccessful biliary cannulation, pancreatic duct stenting was performed in 24 patients. The frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis of the patients without pancreatic duct stenting was significantly higher than that of the patients with pancreatic duct stenting (43% vs 4.2%, P = 0.041; odds ratio, 17; 95% CI, 1.4-210).

Hyperamylasemia at 24 h after ERCP was observed in 68% (68 patients) of the 100 patients with normal serum amylase level before the procedure. Of these patients, the peak serum amylase level was seen at 3 h after ERCP in 8.8% (6 patients), at 6 h in 50% (34), and at 24 h in 41% (28). All of them showed a decrease in serum amylase level at 48-72 h after ERCP. Of the 14 patients who developed post-ERCP pancreatitis, none showed a peak serum amylase level at 3 h after ERCP, six patients showed a peak at 6 h, and eight patients showed a peak at 24 h after ERCP.

Univariate analysis revealed no pancreatic stenting to be the only significant risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis (P = 0.011; odds ratio 5.9; 95% CI, 1.5-22; Table 2). Multivariate analysis also revealed no pancreatic stenting to be the only significant risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis (P = 0.017, Table 3).

Among the 64 patients who underwent pancreatic duct stenting, five patients who required additional ERCP due to various reasons underwent endoscopic removal of the stent at the time of the procedure. Estimation of stent passage was not performed in six patients. Spontaneous migration of the pancreatic stent was observed within two weeks in 92% (49/53) of the patients who had undergone pancreatic duct stenting. In the four patients without passage of a pancreatic stent, two underwent additional endoscopy for removal of the stent. The other two patients refused additional endoscopy. No complications concerning spontaneous passage of the stent occurred.

Selective biliary cannulation is mandatory for therapeutic ERCPs in patients with biliary diseases. Since difficulties in selective cannulation are sometimes encountered due to anatomical constraints or papillary spasm, numerous techniques (papillotome cannulation, precut sphincterotomy, or guidewire cannulation) and pharmacologic aids (cholecystokinin or nitroglycerine spray) have been developed for this purpose[2,3].

Dumonceau et al[4] first reported P-GW for selective biliary cannulation in a patient with surgically altered anatomy. Gotoh et al reported a second case of successful biliary cannulation with P-GW in a patient with a tortuous common channel[5]. P-GW serves several functions advantageous for selective bile duct cannulation, including opening a stenotic papillary orifice, stabilizing the papilla and lifting it up towards the working channel, straightening the pancreatic duct and the common channel, draining the pancreatic duct, potentially minimizing repeated injections into the pancreatic duct, and providing access for placement of a pancreatic stent if necessary[2].

Maeda et al[7] carried out a randomized controlled trial with 53 patients in whom conventional cannulation failed within 10 min, these patients being were assigned to either P-GW (n = 27) or continuation of ordinary techniques (n = 26). Successful biliary cannulation was achieved in 93% of the patients with P-GW compared with 58% in the group of continuation of ordinary techniques (P = 0.0085). They reported a significantly high frequency of hyperamylasemia in the P-GW group, with no incidence of acute pancreatitis. We retrospectively estimated the efficacy and safety of P-GW for biliary cannulation. Although the success rate of biliary cannulation with P-GW in our study was inferior to that of their study (73% vs 93%), the final cannulation rate (86%) in our study was comparable. Patients included in our study were only 2.9% of the patients who underwent ERCP during the same period, and thus they were considered to be extremely difficult cases for biliary cannulation, thus allowing the assessment of success rate of biliary cannulation to be acceptable. It is often emphasized that precut sphincterotomy, which is generally followed by conventional sphincterotomy, should be performed only by expert endoscopists. On the other hand, P-GW can be performed even by endoscopists with less experience in both diagnostic and therapeutic ERCPs without the need for sphincterotomy. Although it entails a potential risk of failure to place a guidewire deeply in a tortuous main duct, P-GW is worth attempting in patients with difficult biliary cannulation before precut sphincterotomy or other invasive techniques are undertaken.

Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in 12% of the patients in our study, in contrast to 0% in Maeda’s study[7]. This is thought to be due to the number of patients included, differences in study population, and definitions of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Deviere commented in his review that Maeda’s data are not sufficient to claim that the risk of pancreatitis will not be increased by this technique because of the small number of patients and the use of confounding medications such as isosorbide dinitrate and urinastatin[10]. One of the major mechanisms of post-ERCP pancreatitis is insufficient pancreatic duct drainage as a result of papillary edema after repetitive manipulation or contrast injections. Therefore, difficult cannulation of the bile duct is given as a risk factor[11]. Since P-GW is attempted in patients with difficult biliary cannulation, it entails a possible increased risk of this particular complication. The efficacy of prophylactic pancreatic stent placement to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis has been reported by prospective randomized controlled trials[12-16]. Fazel et al[13] reported that pancreatic stent (5 Fr, 2 cm or 5 Fr nasopancreatic catheter) insertion reduced the frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis from 28% to 5% in patients at high risk for this complication following difficult cannulation, sphincter of Oddi manometry, and/or sphincterotomy. In our study, post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in 4.7% of patients with pancreatic duct stenting in contrast to 22% of patients without stenting. Non-performance of pancreatic duct stenting was found to be the only significant risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis by univariate and multivariate analysis. Based on these results, we suggest that pancreatic duct stenting is indispensable for P-GW in order to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. Of course, our study had some limitations. First, it was not a randomized or prospective study. Second, routine administration of protease inhibitor might have influenced the frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Third, the usefulness of P-GW was not compared with other methods such as precut sphincterotomy, guidewire cannulation, and so on. Forth, repeated attempts at entering the pancreatic duct with a wire might increase pancreatitis risk. Unfortunately, this study cannot evaluate the risk as patients in whom insertion of a guidewire into the pancreatic duct cannot be achieved were excluded. Further randomized controlled trials are necessary for the evaluation of these points. Nevertheless, our study yielded significant information as regards prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis by pancreatic duct stenting in patients who undergo P-GW.

In conclusion, P-GW is useful for achieving selective cannulation of the bile duct. Pancreatic duct stenting after P-GW can reduce the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis, which should be verified by prospective randomized controlled trials.

Selective biliary cannulation is mandatory for therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) in patients with biliary diseases. Since difficulties in selective cannulation are sometimes encountered due to anatomical constraints or papillary spasm, numerous techniques (papillotome cannulation, precut sphincterotomy, or guidewire cannulation) and pharmacologic aids (cholecystokinin or nitroglycerine spray) have been developed for this purpose.

Pancreatic guidewire placement (P-GW) is reported to be effective in patients with difficult cannulation of the bile duct. However, this technique entails a possible increased risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

In a single-center, retrospective study, selective biliary cannulation with P-GW was achieved in 73% of the patients. Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in 12% after P-GW. Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed no pancreatic stenting to be the only significant risk factor for pancreatitis. Pancreatic duct stenting after P-GW may reduce the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

P-GW is useful for achieving selective biliary cannulation. Pancreatic duct stenting after P-GW can reduce the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis, which requires evaluation by means of prospective randomized controlled trials.

It's an interesting paper. The authors clarified that pancreatic P-GW is useful for achieving selective biliary cannulation in patients with difficult cannulation of the bile duct.

| 1. | McCune WS, Shorb PE, Moscovitz H. Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of vater: a preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1968;167:752-756. |

| 2. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112-125. |

| 3. | Artifon EL, Sakai P, Cunha JE, Halwan B, Ishioka S, Kumar A. Guidewire cannulation reduces risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis and facilitates bile duct cannulation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2147-2153. |

| 4. | Dumonceau JM, Deviere J, Cremer M. A new method of achieving deep cannulation of the common bile duct during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S80. |

| 5. | Gotoh Y, Tamada K, Tomiyama T, Wada S, Ohashi A, Satoh Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Ido K, Sugano K. A new method for deep cannulation of the bile duct by straightening the pancreatic duct. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:820-822. |

| 6. | Hayashi H, Maeda S, Hosokawa O, Dohden K, Hattori M, Tanikawa Y, Watanabe K, Ibe N, Tatsumi S. A technique for selective cannulation of the common bile duct in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Insertion of guidewire into the pancreatic duct. Gastroenterol Endoscopy. 2001;43:828-832. |

| 7. | Maeda S, Hayashi H, Hosokawa O, Dohden K, Hattori M, Morita M, Kidani E, Ibe N, Tatsumi S. Prospective randomized pilot trial of selective biliary cannulation using pancreatic guide-wire placement. Endoscopy. 2003;35:721-724. |

| 8. | Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Kimura K, Yago A. ERCP for intradiverticular papilla: two-devices-in-one-channel method. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatograph. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:517-520. |

| 9. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. |

| 11. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. |

| 12. | Tarnasky PR, Palesch YY, Cunningham JT, Mauldin PD, Cotton PB, Hawes RH. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518-1524. |

| 13. | Fazel A, Quadri A, Catalano MF, Meyerson SM, Geenen JE. Does a pancreatic duct stent prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? A prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:291-294. |

| 14. | Harewood GC, Pochron NL, Gostout CJ. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial of prophylactic pancreatic stent placement for endoscopic snare excision of the duodenal ampulla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:367-370. |

| 15. | Tsuchiya T, Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Kawai T, Moriyasu F. Temporary pancreatic stent to prevent post endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography pancreatitis: a preliminary, single-center, randomized controlled trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:302-307. |

| 16. | Sofuni A, Maguchi H, Itoi T, Katanuma A, Hisai H, Niido T, Toyota M, Fujii T, Harada Y, Takada T. Prophylaxis of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis by an endoscopic pancreatic spontaneous dislodgement stent. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1339-1346. |

Peer reviewer: William Dickey, Altnagelvin Hospital, Londonderry, BT47 6SB, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom

S- Editor Zhong XY L- Editor Rippe RA E- Editor Ma WH