Published online Aug 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4690

Revised: July 4, 2008

Accepted: July 11, 2008

Published online: August 7, 2008

A 53-year old previously healthy male underwent a screening colonoscopy for detection of a potential colorectal neoplasm. The terminal ileum was intubated and a mass was noted. Examination of the colon was normal. The biopsy of the ileal mass was consistent with an adenocarcinoma arising from the terminal ileum. His father who had never been previously ill from gastrointestinal disease died of natural causes, but was found to have Crohn’s disease postmortem. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy and a right hemicolectomy with a 30 cm section of terminal ileum in continuity. Findings were consistent with ileal adenocarcinoma in the setting of Crohn’s disease. The patient made an uneventful recovery. The pathology was stage 1 adenocarcinoma. This is a unique case in that on a screening colonoscopy, a favorable ileal adenocarcinoma was discovered in the setting of asymptomatic, undiagnosed ileal Crohn’s disease in a patient whose father had Crohn’s disease diagnosed postmortem.

- Citation: Reddy VB, Aslanian H, Suh N, Longo WE. Asymptomatic ileal adenocarcinoma in the setting of undiagnosed Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(29): 4690-4693

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i29/4690.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.4690

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is increasing with rates of around 6/100 000 for Crohn’s disease with a marked rise in the age group between twenty to forty years[1]. Small bowel carcinomas are uncommon representing less than 5% of all gastrointestinal malignancies[2–7]. Prognosis is unfavorable with 1 and 2 year survival of 30%-60%, depending on the stage of the cancer[8–12]. Crohn’s disease has been associated with an elevated risk for the development of small bowel adenocarcinoma[913–20] and chronic inflammation is implicated in this neoplastic progression[21]. Although most adenocarcinomas arise in the duodenum, those associated with Crohn’s disease generally occur in the ileum 20 years or more after the onset of Crohn’s disease[91112]. In most cases, detection of small bowel carcinoma associated with Crohn’s disease is at operation for other reasons or due to obstructive symptoms[22–25].

Neither the risk factors nor screening for early diagnosis of small bowel adenocarcinoma in patients with Crohn’s disease have been established. Here we report on an asymptomatic patient who on routine screening colonoscopy was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the terminal ileum which eventually led to the establishment of his Crohn’s disease.

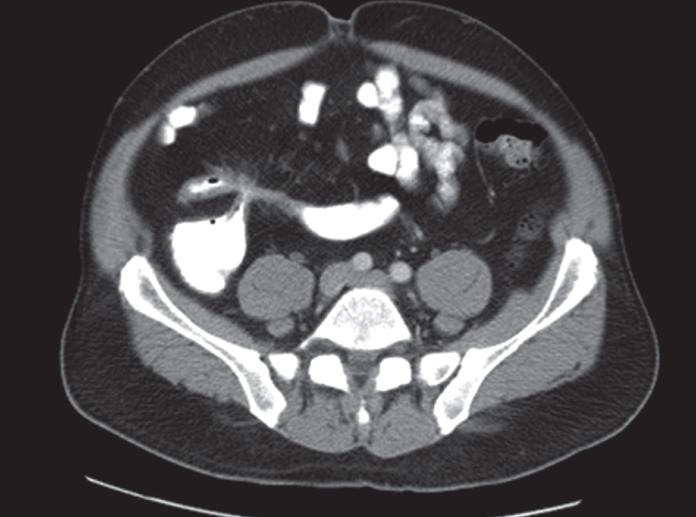

A 53-year old man presented for evaluation of a small bowel mass found on a screening colonoscopy. He denied any episodes of abdominal pain or diarrhea. He noted that his father had been diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at the time of his death. He subsequently underwent a computed tomography (CT) examination of his abdomen and pelvis with both oral and intravenous contrast which revealed a thickened and spiculated wall of the terminal ileum with fistulization from the terminal ileum to the cecum (Figure 1). Given these findings, he was taken to the operating room for exploration.

On exploration, he was found to have a dense inflammatory mass in the right lower quadrant with multiple adhesions to the abdominal wall and bladder. Further exploration revealed a mass in the terminal ileum with dense adhesions involving the terminal ileum and cecum. Given these findings, a right hemicolectomy with a concomitant terminal ileal resection was performed. The surgical specimen consisted of a 20 cm segment of the cecum and a 53 cm segment of the terminal ileum with pericolic fat averaging 9 cm in diameter.

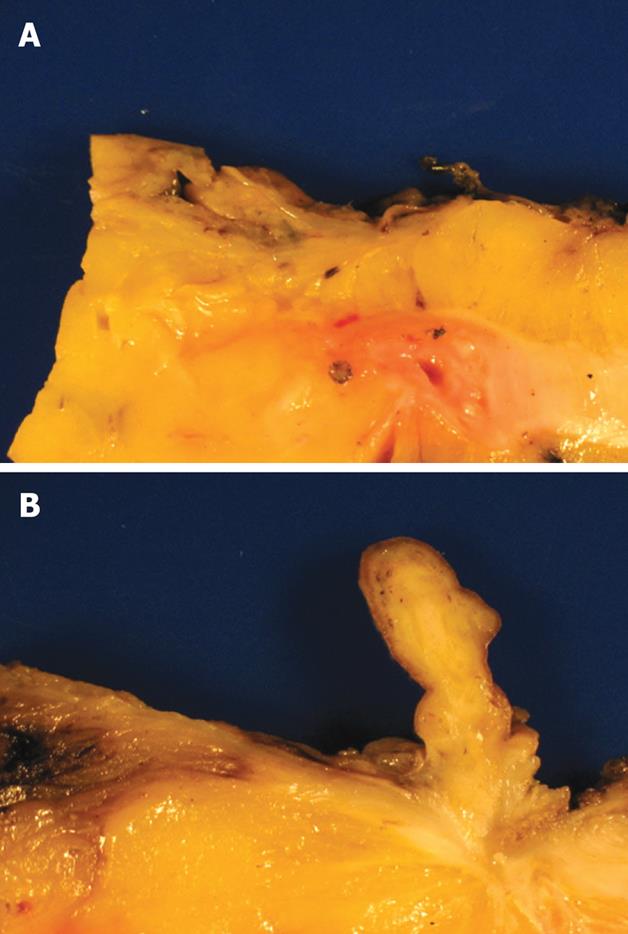

Macroscopic examination revealed Crohn’s disease involving the distal most segment of the terminal ileum with a stricture adjacent to the ileocecal valve (Figure 2A). Adjacent to the stricture was a 3 cm polyp, sections of which revealed a white spiculated area that extended into the underlying fat (Figure 2B).

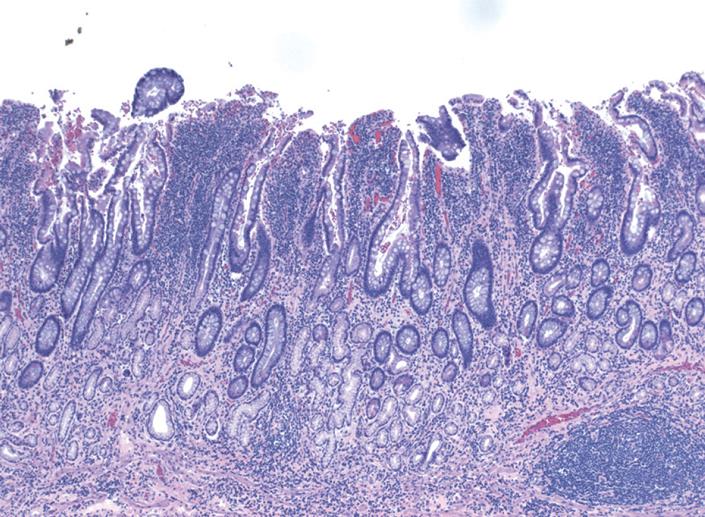

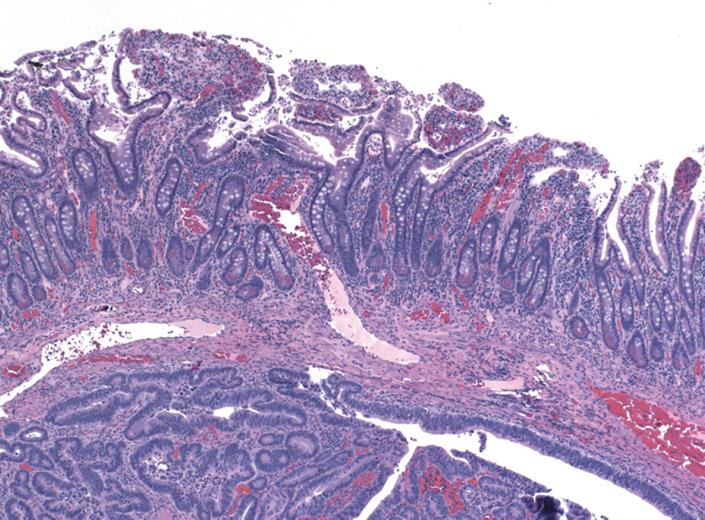

Histopathological examination in the area of the stricture revealed areas of chronic inflammatory change with marked architectural distortion and extensive pseudo-pyloric metaplasia in the mucosa. Extensive transmural lymphoid aggregates, muscular hypertrophy, neural hyperplasia, and submucosal fibrosis, compatible with Crohn’s disease were also noted (Figure 3). In many areas, the mucosa was sitting directly in contact with the muscularis propria without any intervening submucosa. In the background of this inflammation, areas of low and high grade dysplasia were identified. Scattered glands were seen infiltrating into the markedly hypertrophic and disorganized muscularis mucosa. Isolated tumor glands were also seen in the submucosa and as discussed above, in some areas, there were hardly any intervening submucosa with the tumor glands infiltrating the muscularis propria (Figure 4). The size of the tumor was difficult to estimate, as grossly no obvious mass was identified. However, from microscopic sections, it was estimated that the intramucosal carcinoma extended over a 2.0 cm area. The staging of this tumor was also difficult due to complex architecture and histological changes in the bowel wall. However, due to the presence of occasional tumor glands in the muscularis propria, it was staged as pT2. Twenty-nine lymph nodes were harvested and all were negative for carcinoma. The patient recovered well from surgery.

A thorough search of the worldwide literature has revealed that the case presented here is the first ever of a patient with ileal adenocarcinoma as the first manifestation of Crohn’s disease in an otherwise asymptomatic patient. There are, however, other reports of ileal adenocarcinoma as the first manifestation of Crohn’s disease in patients with vague abdominal complaints[2627].

In 1956, Ginzburg et al first described carcinoma as a rare complication of small bowel Crohn’s disease[28]. To date, several cases of small bowel carcinoma in Crohn’s disease have been reported[29]. The most common small bowel carcinoma is adenocarcinoma, and risk factors include long-standing disease, surgically bypassed loops, male sex, onset of disease before the age of 30 years, and associated chronic active disease with strictures and fistulas[1130–32].

Munkholm et al reported an incidence of 0.54% of small bowel cancer in Crohn’s disease compared to an expected rate of 0.04% (P = 0.0001)[30]. In a later study, the same group reported a more than 60-fold increased risk of small bowel adenocarcinoma independent of age and sex in patients with Crohn’s disease[33]. The lifetime prevalence of small bowel adenocarcinoma in patients with Crohn’s disease is 1%-3%[34]. The combination of genetic susceptibility, mechanical irritation and surgery has been suggested as possible etiologies for this elevated risk in Crohn’s disease. Small bowel carcinomas are also mostly localized to strictures[223536]. Immunosuppression has also been implicated[32].

These occult carcinomas pose a challenge to conventional diagnostic investigations such as upper or lower gastrointestinal endoscopy and small bowel series. CT has now emerged as the imaging modality of choice[37–40]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[41], double-contrast enteroclysis[42], and video wireless capsule endoscopy[4344] have also been promising.

Survival rates for small bowel malignancies are much worse than for large bowel cancers with a mean survival of 6 mo as compared to 65 mo for the latter[9]. Mortality rates range from 30%-60% depending on the stage of the carcinoma[8–12]. Poor prognostic factors include positive resection margins, extramural venous spread, lymph node metastases, poor tumor differentiation, depth of tumor, and a history of Crohn’s disease[45].

Only small studies have evaluated adjuvant therapy for small bowel adenocarcinoma[4647]. These studies are not in patients with Crohn’s disease and randomized controlled trials are definitely needed.

We report a patient with ileal adenocarcinoma as the first manifestation of Crohn’s disease. The patient had no symptoms of Crohn’s disease and had only a family history of Crohn’s disease. This case report, as well as others discussed above, highlight the need for a higher index of suspicion in screening for Crohn’s disease and initiating a regular follow-up with ileocolonoscopy.

| 1. | Ekbom A. The epidemiology of IBD: a lot of data but little knowledge. How shall we proceed? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10 Suppl 1:S32-S34. |

| 2. | Wilson JM, Melvin DB, Gray GF, Thorbjarnarson B. Primary malignancies of the small bowel: a report of 96 cases and review of the literature. Ann Surg. 1974;180:175-179. |

| 5. | Cooper MJ, Williamson RC. Enteric adenoma and adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 1985;9:914-920. |

| 7. | Veyrieres M, Baillet P, Hay JM, Fingerhut A, Bouillot JL, Julien M. Factors influencing long-term survival in 100 cases of small intestine primary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 1997;173:237-239. |

| 8. | Solem CA, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Loftus EV Jr. Small intestinal adenocarcinoma in Crohn’s disease: a case-control study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:32-35. |

| 9. | Michelassi F, Testa G, Pomidor WJ, Lashner BA, Block GE. Adenocarcinoma complicating Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:654-661. |

| 10. | Dabaja BS, Suki D, Pro B, Bonnen M, Ajani J. Adenoca-rcinoma of the small bowel: presentation, prognostic factors, and outcome of 217 patients. Cancer. 2004;101:518-526. |

| 11. | Ribeiro MB, Greenstein AJ, Heimann TM, Yamazaki Y, Aufses AH Jr. Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine in Crohn’s disease. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;173:343-349. |

| 12. | Hawker PC, Gyde SN, Thompson H, Allan RN. Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine complicating Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1982;23:188-193. |

| 13. | Nesbit RR Jr, Elbadawi NA, Morton JH, Cooper RA Jr. Carcinoma of the small bowel. A complication of regional enteritis. Cancer. 1976;37:2948-2959. |

| 14. | Beachley MC, Lebel A, Lankau CA Jr, Rothman D, Baldi A. Carcinoma of the small intestine in chronic regional enteritis. Am J Dig Dis. 1973;18:1095-1098. |

| 15. | Frank JD, Shorey BA. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel as a complication of Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1973;14:120-124. |

| 16. | Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Kliewer E, Wajda A. Cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Cancer. 2001;91:854-862. |

| 17. | Torres C, Antonioli D, Odze RD. Polypoid dysplasia and adenomas in inflammatory bowel disease: a clinical, pathologic, and follow-up study of 89 polyps from 59 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:275-284. |

| 18. | Munkholm P. Review article: the incidence and prevalence of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18 Suppl 2:1-5. |

| 19. | Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Colorectal cancer risk and mortality in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1444-1451. |

| 21. | Jess T, Loftus EV Jr, Velayos FS, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Smyrk TC, Schleck CD, Tremaine WJ, Melton LJ 3rd, Munkholm P. Risk of intestinal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study from olmsted county, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1039-1046. |

| 22. | Marchetti F, Fazio VW, Ozuner G. Adenocarcinoma arising from a strictureplasty site in Crohn’s disease. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1315-1321. |

| 23. | Senay E, Sachar DB, Keohane M, Greenstein AJ. Small bowel carcinoma in Crohn‘s disease. Distinguishing features and risk factors. Cancer. 1989;63:360-363. |

| 24. | Cooper DJ, Weinstein MA, Korelitz BI. Complications of Crohn‘s disease predisposing to dysplasia and cancer of the intestinal tract: considerations of a surveillance program. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6:217-224. |

| 25. | Bachwich DR, Lichtenstein GR, Traber PG. Cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Med Clin North Am. 1994;78:1399-1412. |

| 26. | Christodoulou D, Skopelitou AS, Katsanos KH, Katsios C, Agnantis N, Price A, Kappas A, Tsianos EV. Small bowel adenocarcinoma presenting as a first manifestation of Crohn’s disease: report of a case, and a literature review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:805-810. |

| 27. | Mohan IV, Kurian KM, Howd A. Crohn’s disease presenting as adenocarcinoma of the small bowel. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:431-432. |

| 28. | Ginzburg L, Schneider KM, Dreizin DH, Levinson C. Carcinoma of the jejunum occurring in a case of regional enteritis. Surgery. 1956;39:347-351. |

| 29. | Koga H, Aoyagi K, Hizawa K, Iida M, Jo Y, Yao T, Oohata Y, Mibu R, Fujishima M. Rapidly and infiltratively growing Crohn’s carcinoma of the small bowel: serial radiologic findings and a review of the literature. Clin Imaging. 1999;23:298-301. |

| 30. | Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Intestinal cancer risk and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1716-1723. |

| 31. | Bernstein D, Rogers A. Malignancy in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:434-440. |

| 32. | Lashner BA. Risk factors for small bowel cancer in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:1179-1184. |

| 33. | Jess T, Winther KV, Munkholm P, Langholz E, Binder V. Intestinal and extra-intestinal cancer in Crohn’s disease: follow-up of a population-based cohort in Copenhagen County, Denmark. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:287-293. |

| 34. | Kaerlev L, Teglbjaerg PS, Sabroe S, Kolstad HA, Ahrens W, Eriksson M, Guenel P, Hardell L, Launoy G, Merler E. Medical risk factors for small-bowel adenocarcinoma with focus on Crohn disease: a European population-based case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:641-646. |

| 35. | Partridge SK, Hodin RA. Small bowel adenocarcinoma at a strictureplasty site in a patient with Crohn’s disease: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:778-781. |

| 36. | Barwood N, Platell C. Case report: adenocarcinoma arising in a Crohn’s stricture of the jejunum. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:1132-1134. |

| 37. | Furukawa A, Saotome T, Yamasaki M, Maeda K, Nitta N, Takahashi M, Tsujikawa T, Fujiyama Y, Murata K, Sakamoto T. Cross-sectional imaging in Crohn disease. Radiographics. 2004;24:689-702. |

| 38. | Horton KM, Fishman EK. Multidetector-row computed tomography and 3-dimensional computed tomography imaging of small bowel neoplasms: current concept in diagnosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:106-116. |

| 39. | Buckley JA, Siegelman SS, Jones B, Fishman EK. The accuracy of CT staging of small bowel adenocarcinoma: CT/pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1997;21:986-991. |

| 40. | Chen S, Harisinghani MG, Wittenberg J. Small bowel CT fat density target sign in chronic radiation enteritis. Australas Radiol. 2003;47:450-452. |

| 41. | Schreyer AG, Geissler A, Albrich H, Scholmerich J, Feuerbach S, Rogler G, Volk M, Herfarth H. Abdominal MRI after enteroclysis or with oral contrast in patients with suspected or proven Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:491-497. |

| 42. | Zhan J, Xia ZS, Zhong YQ, Zhang SN, Wang LY, Shu H, Zhu ZH. Clinical analysis of primary small intestinal disease: A report of 309 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2585-2587. |

| 43. | Voderholzer WA, Ortner M, Rogalla P, Beinholzl J, Lochs H. Diagnostic yield of wireless capsule enteroscopy in comparison with computed tomography enteroclysis. Endoscopy. 2003;35:1009-1014. |

| 44. | Jungles SL. Video wireless capsule endoscopy: a diagnostic tool for early Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2004;27:170-175. |

| 45. | Abrahams NA, Halverson A, Fazio VW, Rybicki LA, Goldblum JR. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: a study of 37 cases with emphasis on histologic prognostic factors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1496-1502. |

| 46. | Jigyasu D, Bedikian AY, Stroehlein JR. Chemotherapy for primary adenocarcinoma of the small bowel. Cancer. 1984;53:23-25. |

| 47. | Polyzos A, Kouraklis G, Giannopoulos A, Bramis J, Delladetsima JK, Sfikakis PP. Irinotecan as salvage chemotherapy for advanced small bowel adenocarcinoma: a series of three patients. J Chemother. 2003;15:503-506. |