Published online Jul 14, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4222

Revised: May 12, 2008

Accepted: May 19, 2008

Published online: July 14, 2008

AIM: To identify the predictive clinicopathological factors for lymph node metastasis (LNM) in poorly differentiated early gastric cancer (EGC) and to further expand the possibility of using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for the treatment of poorly differentiated EGC.

METHODS: Data were collected from 85 poorly-differentiated EGC patients who were surgically treated. Association between the clinicopathological factors and the presence of LNM was retrospectively analyzed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses.

RESULTS: Univariate analysis showed that tumor size (OR = 5.814, 95% CI = 1.050 - 32.172, P = 0.044), depth of invasion (OR = 10.763, 95% CI = 1.259 - 92.026, P = 0.030) and lymphatic vessel involvement (OR = 61.697, 95% CI = 2.144 - 175.485, P = 0.007) were the significant and independent risk factors for LNM. The LNM rate was 5.4%, 42.9% and 50%, respectively, in poorly differentiated EGC patients with one, two and three of the risk factors, respectively. No LNM was found in 25 patients without the three risk factors. Forty-four lymph nodes were found to have metastasis, 29 (65.9%) and 15 (34.1%) of the lymph nodes involved were within N1 and beyond N1, respectively, in 12 patients with LNM.

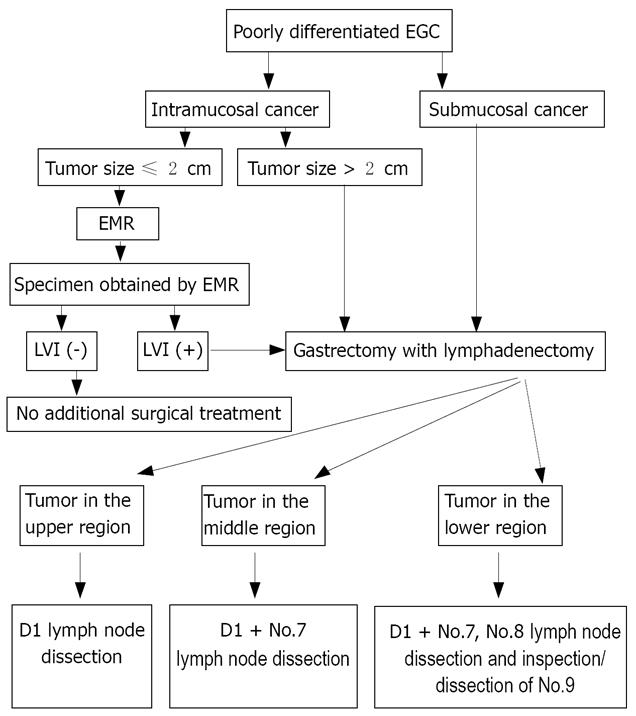

CONCLUSION: Endoscopic mucosal resection alone may be sufficient to treat poorly differentiated intramucosal EGC (≤ 2.0 cm in diameter) with no histologically-confirmed lymphatic vessel involvement. When lymphatic vessels are involved, lymph node dissection beyond limited (D1) dissection or D1+ lymph node dissection should be performed depending on the tumor location.

- Citation: Li H, Lu P, Lu Y, Liu CG, Xu HM, Wang SB, Chen JQ. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in poorly differentiated early gastric cancer and their impact on the surgical strategy. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(26): 4222-4226

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i26/4222.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.4222

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is widely accepted as an alternative treatment for early gastric cancer (EGC)[1–3]. The application of EMR has been limited to differentiated EGC because of the higher risk of lymph node metastasis (LNM) in undifferentiated EGC, compared to differentiated EGC[4–6]. Therefore, gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy is considered an essential treatment for patients with undifferentiated EGC. Undifferentiated gastric cancers include poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma[7]. However, almost all (96.6%) surgical cases of poorly differentiated EGC confined to the mucosa have no LNM[8], suggesting that gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy may be an overtreatment for these cases.

We carried out this retrospectively study to determine the predictive clinicopathological factors for LNM in poorly differentiated EGC. Furthermore, we established a simple criterion for the use of EMR in the treatment of poorly differentiated EGC.

Patients who underwent a radical operation due to EGC in Department of Oncology, First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University (Shenyang, China) between January 1980 and December 2002, were included in this retrospective study.

The inclusion criteria were (1) possible lymph node dissection beyond limited (D1) dissection (i.e. D1 dissection + dissection of lymph nodes along the left gastric artery, D1 dissection + dissection of lymph nodes along the common hepatic artery, D1 dissection + dissection of lymph nodes along the celiac artery) or extended (D2) dissection, (2) pathological analysis of the resected specimens and lymph nodes and poorly differentiated EGC diagnosed according to the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma (JCGC)[7], and (3) availability of medical record of patients from the database.

During the past 23 years, operation was performed in 243 EGC patients. Of the 115 patients who were histologically diagnosed as undifferentiated EGC, 87 had poorly differentiated EGC and 28 had undifferentiated EGC. Among the 87 patients with poorly differentiated EGC, complete medical record of 2 patients was not available. Thus, 85 poorly differentiated EGC patients (60 males, 25 females, mean age of 54 years, range 19-78 years) met the inclusion criteria for further analysis.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University.

Lymph nodes were meticulously dissected from the enbloc specimens, and the dissected lymph nodes by a surgeon after he/she carefully reviewed the excised specimens based on the JCGC[7]. Briefly, lymph nodes were classified into two groups: group 1 as the perigastric lymph nodes and group 2 as the lymph nodes along the left gastric artery, the common hepatic artery, and the splenic artery or around the celiac axis[7].

Accordingly, lymphadenectomy was classified as D1 (i.e. dissection of all the group 1 lymph nodes, D1 + (i.e. dissection of all the lymph nodes along the left gastric artery, lymph nodes along the common hepatic artery, or lymph nodes along the celiac artery), and D2 (i.e. dissection of all the lymph nodes in groups 1 and 2).

The resected lymph nodes were cut into sections which were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined by pathologists for metastasis and lymphatic vessel involvement (LVI).

For classification of LNM, the symbol “No.” was used to indicate the lymph node station number while “N” was used to indicate the lymph node group. For example, No. 1 indicates the right paracardial lymph nodes (Table 1). No. indicates that there was no evidence of LNM. N1 indicates that metastasis was limited to lymph nodes in group 1. N2 indicates that metastasis extended to group 2 lymph nodes (Table 1).

| Lymph node station | Tumor location in the stomach | |||

| Upper | Middle | Lower | Overall | |

| Group 1 (N1) | 1 | 3 | 25 | 29 |

| No. 1, right paracardial nodes | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| No. 2, left paracardial nodes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No. 3, lesser curvature nodes | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| No. 4, great curvature nodes | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| No. 5, suprapyloric nodes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No. 6, infrapyloric nodes | 0 | 0 | 15 | 15 |

| Group 2 (N2) | 0 | 3 | 12 | 15 |

| No. 7, leftt gastric artery nodes | 0 | 3 | 8 | 11 |

| No. 8, common hepatic nodes | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| No. 9, celiac artery nodes | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

The following clinicopathological parameters covered in the JCGC[7] were included in this study, namely the gender (male and female), age (< 60 years, ≥ 60 years), family medical history of gastric cancer, number of tumors (single or multitude), tumor location (upper, middle, or lower of the stomach), tumor size (maximum diameter ≤ 2 cm, or > 2 cm), macroscopic types including protruded (type I), superficially elevated (type IIa), flat (type IIb), superficially depressed (type IIc), or excavated (type III), depth of invasion (mucosa, submucosa), lymphatic vessel involvement.

The associations between various clinicopathological factors and LNM was examined as described below.

All data were analyzed using SPSS13.0 statistical software (Chicago, IL, United States). Differences in the clinicopathological parameters between patients with and without LNM were determined with chi-square test. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed subsequently in order to identify the independent risk factors for LNM. Hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

LNM was histologically confirmed in 12 (14.1%) of the 85 patients. Forty-four metastatic lymph nodes were found in these 12 patients, of which 29 (65.9%) were classified as N1 and 15 (34.1%) as N2. LNM was located in the upper stomach of 1 patient and the observed metastatic lymph nodes belonged to N1. LNM was located in the middle stomach of 2 patients. Of the six observed metastatic lymph nodes, three (50%) belonged to N1 and three (50%) belonged to N2. Of the 37 metastatic lymph nodes observed in the lower stomach of 9 LNM patients, 25 (67.6%) belonged to N1 and 12 (32.4%) belonged to N2 (Table 1).

The association between various clinicopathological factors and LNM was first analyzed with chi-square test (Table 2). Tumor larger than 2.0 cm in diameter (P = 0.007), submucosal invasion (P = 0.009), and the presence of LVI (P < 0.001) were significantly associated with a higher incidence rate of LNM.

| Factor | Lymph node metastasis n (%) | P |

| Sex | ||

| Male (n = 60) | 7 (11.7) | 0.315 |

| Female (n = 25) | 5 (20) | |

| Age (yr) | ||

| < 60 (n = 53) | 9 (17.0) | 0.329 |

| ≥ 60 (n = 32) | 3 (9.4) | |

| Family medical history | ||

| Positive (n = 6) | 1 (16.7) | 0.852 |

| Negative (n = 79) | 11 (13.9) | |

| Number of tumors | ||

| Single (n = 82) | 12 (14.6) | 0.475 |

| Multitude (n = 3) | 0 (0) | |

| Location | ||

| Upper (n = 5) | 1 (20.0) | 0.925 |

| Middle (n = 14) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Lower (n = 66) | 9 (13.6) | |

| Tumor size in diameter | ||

| ≤ 2 cm (n = 45) | 2 (5.1) | 0.007 |

| > 2 cm (n = 40) | 10 ( 21.7) | |

| Macroscopic type | ||

| I (n = 2) | 1 (50.0) | 0.183 |

| II (n = 70) | 8 (11.4) | |

| III (n = 13) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Depth of invasion | ||

| Mucosa (n = 44) | 2 (4.5) | 0.009 |

| Submucosa (n = 41) | 10 (24.4) | |

| Lymphatic vessel involvement | ||

| Positive (n = 4) | 3 (75.0) | < 0.001 |

| Negative (n = 81) | 9 (11.1) |

However, gender, age, family medical history of gastric cancer, number, location, and macroscopic type were not associated with LNM.

Univariate analysis showed that tumor size (OR= 5.814, 95% CI = 1.050 - 32.172, P = 0.044), depth of invasion (OR = 10.763, 95% CI = 1.259 - 92.026, P = 0.030) and LVI (OR = 61.697, 95% CI = 2.144 - 175.485, P = 0.007) were significantly associated with LNM, while multivariate analysis revealed that they were the significant and independent risk factors for LNM.

The LNM rate was 5.4%, 42.9% and 50%, respectively, in poorly differentiated EGC patients with one, two and three of the risk factors, respectively. No LNM was detected in 25 patients without the three risk factors.

One of the critical factors in choosing EMR for EGC would be the precise prediction of whether the patient has LNM. To achieve this goal, several studies have attempted to identify the predictive risk factors for LNM of EGC[9–11]. Few reports, however, have focused on the applicability of endoscopic treatment for poorly differentiated EGC[1213].

In the present study, multivariate analysis revealed that tumor larger than 2.0 cm in diameter, submucosal invasion, and the presence of LVI were the significant predictive factors for LNM in patients with poorly differentiated EGC, which is in consistent the reported findings[9–13].

We then attempted to identify a subgroup of poorly differentiated EGC patients in whom the risk of LNM could be ruled out. As a result, no LNM was found in patients with intramucosal cancer if the tumor is less than or equal to 2.0 cm in diameter without LVI, indicating that EMR is sufficient to treat these patients.

We further examined the relationship between the three predictive factors and the LNM rate in order to establish a simple criterion for the treatment of poorly differentiated EGC. In the present study, the LNM rate was 5.4%, 42.9% and 50%, respectively, in poorly differentiated EGC patients with one, two and three of the risk factors, suggesting that gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy can be performed for these patients with the risk factors.

All the information on these predictive factors, particularly LVI, became evident after histological assessment of the entire specimen. Thus, an accurate histological examination of the endoscopically resected specimen was required to determine whether EMR alone can achieve curative effect. The new EMR technique, complete removal of a large lesion in a single fragment using an insulation-tipped diathermic knife[14–16], is a promising procedure for this purpose.

According to the results of this study, a treatment strategy was proposed for the poorly differentiated EGC patients (Figure 1). EMR alone may be sufficient to treat poorly differentiated intramucosal EGC if it is less than or equal to 2.0 cm in diameter with no LVI. When LVI is found in specimens, an additional gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy should be recommended, with the tumor location taken into consideration. For example, for patients with EGC in the upper stomach, D1 should be performed. However, for patients with EGC in the middle stomach, No.7 lymph nodes should be dissected. For patients with EGC in the lower stomach, No.7 and No.8 lymph nodes should be dissected and No.9 lymph node should be inspected carefully and dissected if LNM is suspected.

In conclusion, EMR alone may be sufficient to treat poorly differentiated intramucosal EGC if it is less than or equal to 2.0 cm in diameter with no LVI. When LVI is found in specimens, D1 or D1+ lymph node dissection should be performed depending on the tumor location.

Gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy is the standard therapy for poorly differentiated early gastric cancer (EGC) with lymph node metastasis (LNM). However, because approximately 96.6% of poorly differentiated intramucosal EGC have no LNM, gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy may be an overtreatment for such patients. We attempted to identify a subgroup of poorly differentiated EGC patients in whom the risk of LNM can be ruled out and treated with endoscopic mucosal resection, which may serve as a breakthrough management of poorly differentiated EGC.

Many clinicians and researchers are undertaking studies of the predictive factors for LNM in EGC. It is widely accepted that lymph node involvement and depth of invasion are closely correlated with LNM. However, the relationship between metastasis and diameter of tumor, histological type and macroscopic type is still controversial. Since LNM remains one of the most important predictors for survival, reduction in lymphadenectomy will probably result in residue of metastatic lymph nodes. Unnecessarily extended resection will induce complications, thus resulting in a poor quality of life.

Tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymphatic vessel involvement are the independent risk factors for LNM. Lymph node dissection is the treatment of choice for poorly differentiated EGC.

Based on the predictive factors for LNM, Lymph node dissection is the treatment of choice for poorly differentiated EGC.

This manuscript presents a rational surgical therapy for poorly differentiated EGC with lymph node dissection and is of interest to clinicians and researchers.

| 1. | Makuuchi H, Kise Y, Shimada H, Chino O, Tanaka H. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 1999;17:108-116. |

| 2. | Ishikawa S, Togashi A, Inoue M, Honda S, Nozawa F, Toyama E, Miyanari N, Tabira Y, Baba H. Indications for EMR/ESD in cases of early gastric cancer: relationship between histological type, depth of wall invasion, and lymph node metastasis. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:35-38. |

| 3. | Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929-942. |

| 4. | Hyung WJ, Cheong JH, Kim J, Chen J, Choi SH, Noh SH. Application of minimally invasive treatment for early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2004;85:181-185; discussion 186. |

| 5. | Abe N, Watanabe T, Sugiyama M, Yanagida O, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y. Endoscopic treatment or surgery for undifferentiated early gastric cancer? Am J Surg. 2004;188:181-184. |

| 6. | Nasu J, Nishina T, Hirasaki S, Moriwaki T, Hyodo I, Kurita A, Nishimura R. Predictive factors of lymph node metastasis in patients with undifferentiated early gastric cancers. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:412-415. |

| 7. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition -. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10-24. |

| 8. | Park YD, Chung YJ, Chung HY, Yu W, Bae HI, Jeon SW, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO. Factors related to lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic mucosal resection for treating poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Endoscopy. 2008;40:7-10. |

| 9. | Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219-225. |

| 10. | Abe N, Watanabe T, Suzuki K, Machida H, Toda H, Nakaya Y, Masaki T, Mori T, Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Risk factors predictive of lymph node metastasis in depressed early gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2002;183:168-172. |

| 11. | Li C, Kim S, Lai JF, Oh SJ, Hyung WJ, Choi WH, Choi SH, Zhu ZG, Noh SH. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in undifferentiated early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:764-769. |

| 12. | Ichikura T, Uefuji K, Tomimatsu S, Okusa Y, Yahara T, Tamakuma S. Surgical strategy for patients with gastric carcinoma with submucosal invasion. A multivariate analysis. Cancer. 1995;76:935-940. |

| 13. | Maehara Y, Orita H, Okuyama T, Moriguchi S, Tsujitani S, Korenaga D, Sugimachi K. Predictors of lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1992;79:245-247. |

| 14. | Gotoda T, Kondo H, Ono H, Saito Y, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Yokota T. A new endoscopic mucosal resection procedure using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for rectal flat lesions: report of two cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:560-563. |

| 15. | Ohkuwa M, Hosokawa K, Boku N, Ohtu A, Tajiri H, Yoshida S. New endoscopic treatment for intramucosal gastric tumors using an insulated-tip diathermic knife. Endoscopy. 2001;33:221-226. |

| 16. | Miyamoto S, Muto M, Hamamoto Y, Boku N, Ohtsu A, Baba S, Yoshida M, Ohkuwa M, Hosokawa K, Tajiri H. A new technique for endoscopic mucosal resection with an insulated-tip electrosurgical knife improves the completeness of resection of intramucosal gastric neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:576-581. |