INTRODUCTION

Chronic viral hepatitis is a common disease in the general population. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection affects 350 million individuals globally, and approximately 15%-40% may develop serious complications, including end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma[1]. Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is also an important cause of chronic hepatitis, data from World Health Organization (WHO) suggesting that 170 million people are infected world-wide with HCV, 10 million of them in Western Europe[2]. It is estimated that at least 3.9 million persons (1.8% of the population) in the United States are anti-HCV seropositive, and that 2.7 million are chronically viremic[3].

At the same time, alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are frequent in the developed countries. Regarding NASH, long-term follow up studies on obese patients showed increased cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality[4]. Also, studies on cohorts of diabetic patients showed increased incidence of non-alcoholic chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma[5].

The complete evaluation of a patient with diffuse liver diseases requires: clinical evaluation, biological evaluation and morphopathological exam-liver biopsy (LB), for the grading and staging of the liver disease. The clinical evaluation is often irrelevant, only the presence of spider naevi on the anterior thorax or an enlarged and firmer liver could suggest that the patient already has liver cirrhosis (suspicion that has to be confirmed or infirmed by further tests). The biological evaluation by means of the usual tests is also often irrelevant, especially in chronic hepatitis C, known to induce sometimes severe hepatic lesions, while the aminotransferases are normal or only slightly elevated. Thus, it is considered that the liver biopsy has a key role for the diagnosis and follow-up of chronic diffuse hepatopathies, especially for the staging of chronic hepatitis C[6–9].

So, what is the utility of LB in chronic liver disease? Fontolliet[6] stated that LB has the following roles: to confirm the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis; to assess the necro-inflammatory activity (grading) and the severity of fibrosis (staging); to exclude another hepatopathy or an associated disease; to certify the diagnosis of cirrhosis (when present).

A review of the short history of LB shows us that: Paul Ehrlich is credited with performing the first percutaneous LB in 1883 in Germany; Sheila Sherlock described the percutaneous LB technique in 1945 and after Menghini reported a technique for the “one-second needle biopsy of the liver” in 1958, the procedure became more widely used[10].

But did the LB become a method of diagnosis unanimously accepted by the patients and the doctors? To answer this question we will present the results of a French study, performed on 1177 general practitioners that showed that 59% of the patients infected with HCV refused the LB, opinion shared by 22% of the general practitioners[11].

All these being said, we would like to discuss in this paper several aspects concerning the LB, trying to answer the following questions: (1) Why? (2) Who? (3) How to perform the LB?

WHY TO PERFORM A LB IN CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE?

During chronic hepatitis, the prognosis and clinical management are highly dependent on the extent of liver fibrosis[12]. The fibrosis evaluation can be performed by means of: FibroTest-using serological markers; Elastography or FibroScan-a noninvasive percutaneous technique using the elastic property of the hepatic tissue; liver biopsy-that seems to be the “gold standard”.

FibroTest

The non-invasive tests for the assessment of the severity of chronic liver diseases are an interesting alternative, more and more evaluated in the last years, aimed to replace, maybe, the LB. After 2000, the non-invasive tests predictive of liver damage were studied more and more, especially in chronic hepatitis C[13] and, more recently, also in chronic hepatitis B[14] and NASH[15–17].

FibroTest-ActiTest (FT-AT) was developed using biochemical markers and repeatedly demonstrated a high predictive value for fibrosis and necroinflammatory histological activity, in patients with chronic hepatitis C[18–21]. In two separate studies the FT-AT has been proven valuable also in patients with chronic hepatitis B[1422].

FT-AT is a noninvasive blood test that combines the quantitative results of six serum biochemical markers (alfa2-macroglobulin, haptoglobin, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase, total bilirubin, apolipoprotein A1 and ALT) with patients’ age and gender in a patented artificial intelligence algorithm (USPTO 6631330) in order to generate a measure of fibrosis and necroinflammatory activity in the liver[14]. Previously validated FT-AT are used (Biopredictive, Paris, France; Fibro-SURE LabCorp, Burlington, NC), that provide an accurate measurement of bridging fibrosis and/or moderate necroinflammatory activity with AUROC (Area Under Receiver-Operating Characteristic Curve) predictive value between 0.70 and 0.80, when compared to the liver biopsy[23].

It is recommended that FibroTest-ActiTest should not be performed during Ribavirin therapy, because it can induce hemolysis and low haptoglobin levels, nor in patients with Gilbert's syndrome, with acute hepatitis or extra hepatic cholestasis[23], cases in which falsely elevated fibrosis and activity scores can be obtained.

In a recently published editorial in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, Paul Thuluvath[24] discusses the FibroTest, stating that it was extensively studied only by Poynard et al and that there are only few independent studies. It is also considered that there are significant inter-laboratory variations, thus some studies demonstrated that significant fibrosis can be over-looked or over-rated in approximately 15%-20% of the cases. As a conclusion of this editorial, Paul Thuluvath considers that “we may be approaching a time when serum biomarkers may become an integral part of the assessment of patients with chronic liver disease, but published evidence suggests that these markers are not yet ready for prime time”.

Elastography or FibroScan

Another non-invasive method of assessment of liver fibrosis is transient elastography. This technique enables the assessment the liver's stiffness and it is performed by a device called FibroScan (Echosens). The main component of the FibroScan is an ultrasound probe mounted on a vibrating device (piston). The patient to be examined lies down on his back and the ultrasound probe is applied to the skin surface between the ribs, thus examining the right liver lobe. The piston induces elastic vibrations, with low frequency and small amplitude that propagate through the liver. The reflected waves are captured by the transducer, their velocity being directly related to the elasticity (stiffness) of the liver. After several elastographic measurements are performed, the mean value must be calculated, thus enabling a correct assessment of the fibrosis.

This method of evaluation is totally painless and lasts only a few minutes. The stiffness of the liver is measured up to 2 cm in depth and on a surface with the diameter of approximately 1 cm (thus enabling the evaluation of a portion of the liver 500 times bigger than by LB)[25]. In the study performed by Foucher et al[26] the stiffness of the liver was measured up to a depth of 4 cm and on a surface with the diameter of 1 cm, so that 1/500 of the liver was evaluated. However the FibroScan device is exceedingly expensive rising to more than 60 000 Euros.

The value of the FibroScan method for the assessment of the severity of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis is under evaluation, but in the last 2 years several papers were published that demonstrate that this non-invasive method is precise enough to be compared to LB[1225–28].

In the study performed by Castera et al, the elasticity of the liver, measured with the FibroScan device, varied between 2.4 and 75.4 kilopascals (kPa), with a median of 7.4 kPa[27]. When comparing the FibroScan to the LB in patients with chronic hepatitis C, the cut-off values were 7.1 kPa for F ≤ 2; 9.5 kPa for F ≤ 3 and 12.5 kPa for F = 4[27]. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of FibroScan was 0.83 for F ≤ 2; 0.90 for F ≤ 3 and 0.95 for F = 4[27]. The same authors demonstrated that, when combined with FibroTest, FibroScan was more precise than the LB, the AUROC values reaching 0.88, 0.95 and 0.95 respectively, for fibrosis ≤ 2, ≤ 3 or 4.

In a study performed by Ziol et al[12] the AUROC value of FibroScan as compared to the LB was 0.79 for F ≤ 2; 0.91 for F ≤ 3 and 0.97 for F = 4. Thus, the authors concluded that transient elastography appears reliable to detect significant fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

The majority of studies that compared the FibroScan to the FibroTest and to the LB showed a slight superiority of FibroScan vs FibroTest[2728].

Starting from the encouraging results of FibroScan in patients with chronic hepatitis C, this method was also used to evaluate the severity of fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B and in patients with primary billiary cirrhosis (PBC)[2930].

It is probable that in a not too far future, the combination of FibroScan with FibroTest could avoid biopsy in most patients with chronic hepatopathies[27].

FibroTest and Elastography have a good value for the cases with no fibrosis or with important fibrosis (cirrhosis), but for the intermediate stages the value is low. This is the reason why LB is still the most used method of assessment of the severity of liver lesions in chronic hepatitis, several guidelines recommending that the decision to treat should be made after liver biopsy[3132].

Liver biopsy

At this moment LB is still the “gold standard” for the evaluation of chronic hepatitis[33], but the method is not perfect. There are some problems regarding the diagnosis of cirrhosis by LB[33] and regarding the differences of the severity of fibrosis when twin LB are performed in both liver lobes[34]. This is why we consider appropriate a review of the advantages of LB, of its limits, of the best techniques to perform LB and also of the possible complications.

How representative can be a needle biopsy? The size of a biopsy specimen, which varies between 1 cm and 4 cm in length and between 1.2 mm and 1.8 mm in diameter, represents 1/50 000 of the total mass of the liver[31]. The British guideline about LB[31] considers that most hepatologists are satisfied with a biopsy specimen containing at least six to eight portal triads. A critical review of the literature reveals that biopsy samples 2 cm or more in length, containing at least 11 complete portal tracts, should be reliable for grading and staging chronic viral hepatitis[35]. Another study, concerning the dimensions of the biopsy specimen needed in order to perform an accurate pathological diagnosis, demonstrated that a fragment of at least 10 mm is enough for a correct staging and grading[36].

But which is the main reason to perform liver biopsy? The answer is: chronic hepatitis C. In our Department of Gastroenterology, the last 1500 LB were performed to evaluate: chronic C viral infection in 56.0% of the cases; chronic B viral infection in 34.2% of the cases; chronic viral coinfection in 3.2% of the cases; NASH and ASH in 4.5% of the cases and other liver diseases in 1.7% of the cases[37].

In France, in a nationwide survey, Cadranel et al[38] showed that 54% of the LB were performed for chronic C viral infection. The total number of LB performed each year in France is approximately 16 000[39].

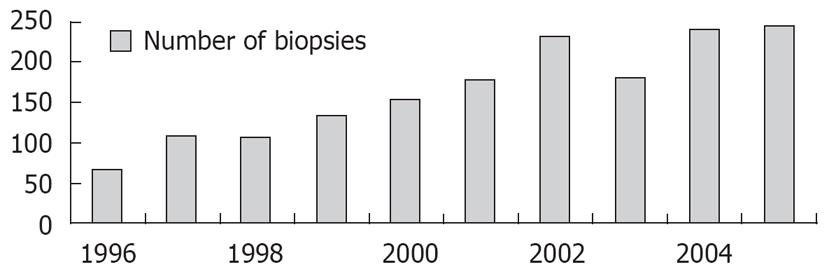

The number of LB performed in every department increased in the last 15 years, mainly due to the increasing number of cases with chronic hepatitis C discovered in the last period, but we do not know the future trend, in connection to the introduction of non-invasive tests of fibrosis. The evolution of the number of ultrasound guided LB in our department in the last 10 years is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Liver biopsies performed in our department in the last years (1996-2005).

WHO SHOULD PERFORM THE LIVER BIOPSY?

There are two main categories of specialists who perform LB: gastroenterologists/hepatologists and the radiologists. The specialty of the individual who performs the LB determines if the LB is performed under ultrasound (US) guidance or not.

In many countries the ultrasound examination is performed both by radiologists and by clinicians (Germany, Italy, Austria, Switzerland and Romania). In other countries, the ultrasound examination is performed only by radiologists (USA, UK, The Netherlands and Denmark).

Currently it is estimated that in the USA, 50% of the LB are performed by radiologists[40]. In the same country, a questionnaire regarding the LB practice, answered by 112 gastroenterologists/hepatologists, showed that 30% of them do not perform LB (due to concern about risks, low reimbursement and logistical issues)[41]. Another important fact is that in countries in which gastroenterologists do not perform US examinations, the LB performed by the clinician are “blind”, or done by the radiologist. It was suggested in USA that, by installing a US machine in the endoscopy unit, the cost of LB would decrease because a previous US examination in the Radiology Department would not be necessary before the LB, but that would require the gastroenterologist and hepatologist to become proficient in US technique and interpretation[40].

The European Diploma of Gastroenterology stipulates that, in order to become specialists, all the gastroenterologists should perform at least 300 US examinations[42]. In the opinion of Vautier’s team, issued years ago, “the ideal liver biopsy may be one that is performed in the ward by a gastroenterologist using ultrasonographic guidance”[43].

HOW TO PERFORM LB?

Currently, there are 3 techniques for performing a liver biopsy[31]: percutaneous, transjugular and laparoscopic. The percutaneous liver biopsy (PLB) can be performed: blind, US guided or US assisted.

The most important question regarding the percutaneous liver biopsy that should be addressed is: blind or echo-guided techniques? The answer depends on the skills of the gastroenterologist (hepatologist) and on the technical possibilities (accessibility to the ultrasound machine).

However, it is still debatable whether ultrasound-guided LB has an advantage over the blind one or not[4344]. In a prospective study in France, Cadranel et al[38] showed that from 2084 liver biopsies, only 56% were echo-guided. Also, many studies showed that the complications of LB seem to be related to the type of the technique, blind or echo-guided, respectively: (1) Younossi et al[45] showed that the complications appeared in 4% of the cases with “blind” biopsies and in 2% of the cases with “ultrasound-guided” biopsies (the study revealed the cost-effectiveness of echo-guided biopsy); (2) Farrell et al[46] showed complications in 1.8% of the cases with “ultrasound-guided” biopsies and in 7.7% of the cases with “blind” biopsies (P < 0.05); (3) Pasha et al[44] showed that severe complications occurred in 0.5% of the cases with “ultrasound-guided” biopsies and in 2.2% of the cases with “blind” biopsies (P < 0.05). The same author revealed that the pain appeared more often (50% of the cases) in the “blind” biopsy group as compared to the “ultrasound-guided” biopsy group (37% of the cases, P = 0.003).

But how often does the ultrasound guidance change the liver biopsy site? In a prospective study, Riley[47] showed that by ultrasound examination the site of biopsy was changed in 15.1% of the cases (21/165 patients). The reasons for changing the place of biopsy were the interposition of: lung, gall bladder, large central vessel, ascites, colonic loop, and slim liver edge.

Considering all these facts, it is reasonable and cost-efficient to perform the LB under US guidance[4045], recent data suggesting a decrease in severe postbiopsy complications by up to 30% and less postbiopsy pain[40].

Type of needle

There are two types of biopsy needles used to perform a LB: “cutting needles” (Tru-Cut, Vim-Silverman) and “suction needles” (Menghini needle, Klatzkin needle, Jamshidi needle). Regarding how we use the needle, we can perform the LB manually or automatic, using spring-loaded devices (the so called “gun system”).

Data from literature showed that there is a correlation between the rate of complications and the type of the needle used for biopsy: 3.5‰ for the Tru-Cut needle and 1‰ for the Menghini type needle[48].

Usually the choice of the biopsy instrument/needle is based on operator preference, instrument availability and clinical scenario[40]. The choice between the automatic biopsy gun vs manual activated needle depends on the experience of the center (operator). In a Dutch study[49] that compared standard Tru-Cut needle with a new automatic biopsy gun (Acecut), the performance of the automatic needle was superior and more consistent with respect to tissue yield, but post-biopsy pain and post-biopsy use of analgesics was superior after automatic biopsy gun. Thus, the authors[49] conclude that the automatic Tru-Cut needle offers an advantage, particularly for physicians with no or limited experience in liver biopsy.

Another group[50] did not find either type of needle to offer more safety when comparing the Tru-Cut needle with an automatic biopsy needle.

In a personal prospective study[37], we compared the number of portal spaces obtained after PLB performed with a modified Menghini needle (manual activated needle) to the number of portal spaces obtained by PLB performed with an automatic needle (Auto Vac). The mean number of portal spaces obtained by Menghini needle biopsy was 14.03 ± 7.48, and by automatic needle biopsy was 8.81 ± 4.35 (P < 0.0001).

The size of the needle

Usually the size of the biopsy needle used for LB in chronic hepatopathies varies between 1.2 and 1.8 mm. Gazelle’s group[51] showed that larger needles produce more bleeding after LB in anaesthetized pigs (by comparing 2.1 mm with 1.6 mm needles and also by comparing 1.6 mm with 1.2 mm needles). Another study performed by Plecha et al[52], using cutting needles of 14, 18 and 22 gauge on porcine models, showed that the larger is the caliber of the needle, the greater is the absolute blood loss, but the conclusion of the study was that the use of larger-caliber needles is more efficient, despite the greater amount of blood loss, because more tissue can be recovered and because fewer passes are necessary, thus reducing the chance of complications.

However, other studies concerning the size of the needle in connection with the rate of hemorrhagic complications, performed in humans, did not show any difference[46].

The number of passes of the needle into the liver

It has been demonstrated that taking more than one biopsy can increase the diagnostic value, but may have an effect on morbidity[3839475354]. In a study performed by Riley[47] on 165 patients, only in 1.8% of cases multiple passes were necessary (noting that a low multiple pass rate was observed when applying ultrasound guidance), but in another study[55], two needle passes were required in 20% of the patients and 3 needle passes in 0.2% of the cases.

From our point of view, after a long experience in performing PLB, we consider that the visual inspection of the hepatic fragment obtained by LB represents the guarantee that enough histological material was obtained. If we are unhappy with the size of the specimen, we perform another hepatic pass in the same session, rather than make a new biopsy later.

The experience of the operator

There are controversial results regarding this issue. In one study, Gilmore et al[55] showed that the rate of complications in PLB was 3.2% if the operator had performed less than 20 biopsies and only 1.1% if the operator had performed more than 100 biopsies. In the study of Chevalier’s group[56] the operator’s experience did not influence either the final histological diagnosis or the degree of pain suffered by the patients.

The safety of PLB

In a very large multicentric retrospective study concerning 98 445 liver biopsies, Poynard et al[57] showed that the LB was followed by severe adverse events in 3.1‰ of the cases and by mortality in 0.3‰ of the cases. In another large study the mortality rate from fatal hemorrhage after PLB was 0.11%[58]. In the well-known retrospective study performed by Piccinino et al[48] on 68 276 PLB, death was infrequent (0.09/1000 biopsies). The rate of major complications after PLB ranges from 0.09% to 2.3%[40], while in a French study, severe complications appeared in 0.57% of cases[38].

Another important question is: when did the post biopsy complications appear? From the retrospective multicentric study of Piccinino[48] we found that 61% of the complications appeared in the first 2 hours after the biopsy, 82% in the first 10 hours and 96% in the first 24 hours after biopsy. Some studies showed that the rate of complications is similar in out or inpatients[5859].