Published online May 28, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3224

Revised: March 11, 2008

Accepted: March 18, 2008

Published online: May 28, 2008

AIM: To study the factors that may affect survival of cholangiocarcinoma in Lebanon.

METHODS: A retrospective review of the medical records of 55 patients diagnosed with cholangio-carcinoma at the American University of Beirut between 1990 and 2005 was conducted. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to determine the impact of surgery, chemotherapy, body mass index, bilirubin level and other factors on survival.

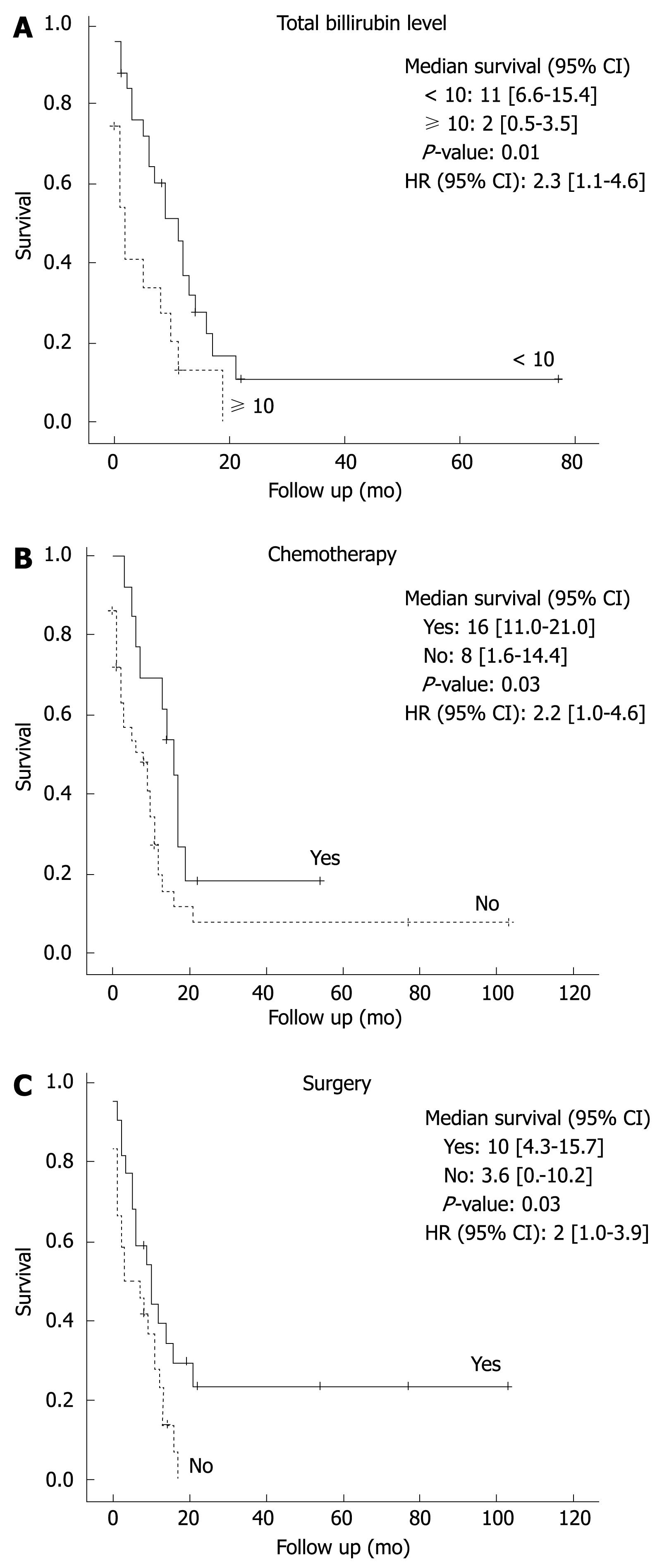

RESULTS: The median survival of all patients was 8.57 mo (0.03-105.2). Univariate analysis showed that low bilirubin level (< 10 mg/dL), radical surgery and chemotherapy administration were significantly associated with better survival (P = 0.012, 0.038 and 0.038, respectively). In subgroup analysis on patients who had no surgery, chemotherapy administration prolonged median survival significantly (17.0 mo vs 3.5 mo, P = 0.001). Multivariate analysis identified only low bilirubin level < 10 mg/dL and chemotherapy administration as independent predictors associated with better survival (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Our data show that palliative and postoperative chemotherapy as well as a bilirubin level < 10 mg/dL are independent predictors of a significant increase in survival in patients with cholangiocarcinoma.

- Citation: Farhat MH, Shamseddine AI, Tawil AN, Berjawi G, Sidani C, Shamseddeen W, Barada KA. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma: Role of surgery, chemotherapy and body mass index. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(20): 3224-3230

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i20/3224.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.3224

Cholangiocarcinoma is a rare and highly fatal neoplasm that arises from biliary epithelium. It constitutes approximately 2% of all reported cancer[1], and accounts for about 3 percent of all gastrointestinal malignancies[2]. Up to date, radical surgery remains the optimal therapy for cholangiocarcinoma offering a potential for cure[134]. In surgical patients with negative margins, five-year survival rates approach 20%-35% as compared to zero in those with positive margins[5]. However, most patients present with advanced disease precluding surgery[6–8]. Overall prognosis in these patients is poor and survival is limited to a few months[9]. Thus, it is crucial to identify factors that would improve survival in such patients.

The role of chemotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma is yet to be determined, with conflicting data regarding its effect on survival. This is due to lack of randomized clinical trials, and absence of a standard chemotherapeutic regimen[10]. While some authors believe that chemotherapy prolongs survival in cholangiocarcinoma[1112], others deny this survival benefit[13–15].

The impact of excess body weight on survival in patients with different cancers is variable. While it is associated with improved survival in patients with cancers of the gastric cardia[16], less aggressive disease in renal cell cancers[17], and lower malignant potential in ovarian tumors[18], it was found to increase mortality in early stage breast cancers[19], cancer of the esophagus, colon and rectum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and kidney[20]. However, the relationship of increased body mass index (BMI) and survival in cholangiocarcinoma has not been thoroughly investigated.

Many factors are well known to increase the risk of cholangiocarcinoma; these include age, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), hepatolithiasis, and liver flukes[6].

Several studies have provided evidence that excess body weight and obesity increase the risk of overall cancers. In a study by Lee et al, overweight people had a one and a half times increased risk of cancer compared to those with normal weight in both sexes[21]. Similarly, obese people had a 33% increase in overall cancer incidence[22]. In cancers of the biliary tract, cancer of the gall bladder was linked previously with increased BMI in women[2324]; whether increased BMI is a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma is not known yet. In our study, the effect of increased BMI was given special emphasis to investigate its role as a risk factor and as a prognostic indicator.

In this study, we sought to determine the clinico-pathologic characteristics of patients with cholangio-carcinoma. We also tried to identify the determinants of prognosis and survival in those patients with special emphasis on the role of surgery, chemotherapy and BMI.

Patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma at the American University of Beirut-Medical Center during the 15 year period between 1990 and 2005 were identified. Patients’ demographics, clinical data, radiological and histopathologic findings, surgical intervention, chemotherapy administration, and survival data were obtained retrospectively from hospital medical charts and by contacting patients or their family members. All histopathology slides and radiographic studies were reevaluated by a pathologist and a radiologist to obtain data about tumor location, grade, stage, lymphatic spread, vascular invasion and metastasis.

Tumors were classified as intrahepatic if originating from intrahepatic ductules (proximal to the bifurcation of the right and left hepatic ducts), and extrahepatic if perihilar (involving the confluence of the right and left bile ducts) or distal (if originating distal to the confluence of hepatic ducts).

AJCC 2003 criteria were used for TNM staging of the tumor[25].

The impact of high bilirubin level at presentation, tumor location, size, grade, metastasis, presence of vascular or perineural invasion, positive surgical margins, type of treatment including palliative stenting, surgery and chemotherapy on survival was examined.

Parameters examined as possible risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma were age, gender, diabetes, BMI, history of cholelithaisis, Hepatitis B and C infection, smoking, alcohol consumption, presence of cirrhosis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), PSC, and parasitic infestations.

To determine if increasing BMI is a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma, patients were compared to controls of the same age groups that were selected from a large study about obesity in the Lebanese population[26]. According to WHO standards[27], subjects were categorized according to their body mass index (normal: < 25, overweight: 25-30, and obese: ≥ 30 kg/m2).

All data was coded and entered using SPSS 14.0 computer program. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival which was measured from time of presentation to AUB-MC to the date of death or date of last follow up. Differences in survival between subgroups were compared using the log-rank test. Univariate analysis was performed using the chi-squared testing. Multivariate analysis was performed with the Cox proportional hazards model. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

During the 15-year period, a total of 55 patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma were studied. The demographic and clinical data of all patients are listed in Table 1. There were 34 males (60.7%) and 22 (39.3%) females. The mean age for all patients was 62.6 ± 13.0 years and ranged from 28 years to 91 years. Seventeen patients were older than 70 years (11 females and 8 males). In males, the incidence of the tumor was highest in the age group of 50-59 years, while in females it was in the older than 70 years age group.

| Number of patients (%) | ||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 62.6 ± 13 | |

| Range (yr) | 28-91 | 61/39 |

| Male/Female | 34/22 | |

| Diabetes (Yes/No) | 14/41 | 25/75 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| < 25 | 18 | 35 |

| 25-30 | 16 | 31 |

| ≥ 30 | 18 | 35 |

| Not available | 3 | |

| History of cholelithiasis (Yes /No) | 17/38 | 31/69 |

| Clinical manifestations | ||

| Jaundice | 40 | 72.7 |

| Dark urine | 34 | 61.8 |

| Weight loss | 24 | 43.6 |

| Abdominal pain | 24 | 43.6 |

| Total bilirubin | ||

| < 10 mg/dL | 27 | 49 |

| ≥ 10 mg/dL | 17 | 31 |

| Missing | 11 | 20 |

| AJCC staging | ||

| I | 1 | |

| II | 1 | |

| III | 0 | |

| IV | 49 | 89 |

| Missing | 4 | |

| Surgery | ||

| Yes | 21 | 38 |

| No | 34 | 62 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 14 | 25 |

| No | 41 | 75 |

The most common presenting symptoms were jaundice (72.7%), dark urine (61.8%), weight loss (43.6%), abdominal pain (43.6%), pruritus (36.4%), and fever (10.9 %).

None of the patients had primary sclerosing cholangitis or any evidence of parasitic infestation on histological examination. One patient had inflammatory bowel disease (1.8%). One patient had a history of hepatitis B infection and two had liver cirrhosis of unknown etiology (3.6%). Ten patients had a history of cholecystectomy (17.8%) and 17 had a history of cholelithiasis (30.9%). Fifteen patients had a history of diabetes mellitus (25.5%) and one third (33%) were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). One patient had a family history of cholangiocarcinoma (1.8%).

Tissue diagnosis was obtained on 30 patients (54.5%). Histopathologic findings are listed in Table 2. Tumors larger than 3 cm, as measured in resected specimens and by radiology, comprised 34.5%, compared to 23.6% for those less than 3 cm. The most common morphological type was intraductal growing (n = 34, 61.8%) followed by mass forming (n = 21, 38%). Mass forming morphology was present in 63% and 35% of intrahepatic and extrahepatic tumors, respectively, with periductal infiltrating morphology comprising the rest of the patients.

| n | Median survival (95% CI) | P | |

| Location | |||

| Intrahepatic | 10 | 6.23 (0.76-11.7) | 0.68 |

| Perihilar | 18 | 11.47 (6.73-16.2) | |

| Distal | 21 | 9.17 (0.52-17.8) | |

| Not available | 6 | ||

| Size | |||

| < 3 cm | 19 | 3.47 (1.9-5.0) | 0.31 |

| ≥ 3 cm | 13 | 11 (4.13-17.87) | |

| Not available | 23 | 13 | |

| Grade | |||

| Poor | 4 | 16.96 (8.9-25.0) | 0.31 |

| Moderate | 15 | 11 (2.77-19.2) | |

| Well | 8 | 13 (0-31) | |

| Missing | 28 | ||

| Margin status | |||

| Positive | 7 | 9.9 (4.6-15.19) | 0.90 |

| Negative | 14 | 14.3 (5.5-23.1) | |

| Vascular invasion | |||

| Yes | 7 | 22 (4.9-39.2) | 0.78 |

| No | 14 | 10.2 (4.04-16.42) | |

| Perineural involvement | |||

| Yes | 10 | 6.2 (4.9-7.5) | 0.66 |

| No | 13 | 11 (5.8-16.2) |

Tumor grade was available on 27 patients. They were mostly moderately (55.6%) and poorly differentiated (29.6%). Vascular involvement on histology was evident in 12 patients (21.8%), while perineural invasion was found in 10 patients (18.2%).

Tumors presented at stage IV in 49 out of 55 patients (89%).

Distribution of tumor could be obtained on 48 patients (Table 2). Thirty-seven tumors (67.2%) were extrahepatic versus 11 intrahepatic (20%).

Of the extrahepatic tumors, 19 were distal (34.5%) and 18 were perihilar (32.7%). Nineteen patients had metastatic disease. The most common sites of metastases were the liver (25.4%, n = 14/55), followed by the peritoneum (10.9%, n = 6/55). Two patients had lymph node metastasis. One patient had brain metastasis and another had bone metastasis.

The resection rate of the tumor was low (21/55, 31.8%). Rate of radical operation was only 11% (6/55). Extrahepatic tumors were more resectable (n = 13, 23.6%) as compared to intrahepatic tumors (n = 6, 10.9%). In 2 surgical patients, location of tumor could not be ascertained.

Of the twenty one patients who underwent surgery: 6 had Whipple procedure, 6 hepatic resection, and 9 enbloc resection of bile ducts and gall bladder. Two patients had positive lymph nodes. Surgical margins were positive in 7 patients (n = 7/21, 33%). Thirty-four patients had unresectable disease because of gross vascular involvement, locally advanced disease, or peritoneal metastasis discovered by imaging or during surgical exploration.

Twenty-four patients underwent palliative stenting, 9 had endoscopic stenting (37.5%), 14 had percutaneous radiological stenting (58.3%), and only one patient underwent surgical stenting (4.2%).

Fourteen patients received chemotherapy in the form of postoperative chemotherapy (n = 6) or as palliative in the setting of non-resectable disease (n = 8). Chemotherapy regimens consisted of gemcitabine or 5-Fu. Gemcitabine was given mainly as a single agent. As part of combination therapy, it was co-administered with other drugs such as oxaliplatin, 5-Fu, or CPT-11. 5-Fu was given as part of combination therapy at all times.

The median survival for all patients was 8.57 mo (0.03-105.2), with 1-year, 3-year and 5-year survival rates of 10.8%, 5.4%, and 5.4%, respectively.

The longest survival time among all patients was 103 mo.

Multiple clinical, tumor-related and treatment parameters were evaluated by univariate analysis to determine their impact on survival in cholangiocarcinoma (Table 3). Parameters that did not influence survival were age, gender, diabetes, history of cholelithiasis, type of operation, resection margin status, presence of metastasis, and stenting. Tumor size, grade, location, vascular and perineural invasion also did not impact survival (Table 2). Increasing BMI was associated with a non-significant decrease in

| Variable (n) | Median survival (mo) | P (Univariate) |

| Age | ||

| < 50 (11) | 10.23 (1.87-18.6) | 0.410 |

| ≥ 50 (44) | 9.17 (3.9-14.4) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male (33) | 9.17 (3.8-14.5) | 0.386 |

| Female (22) | 9.9 (0.4-19.4) | |

| Bilirubin | ||

| < 10 (27) | 9.9 (3.1-16.7) | 0.012 |

| ≥ 10 (17) | 2.87 (1.2-4.5) | |

| BMI | ||

| < 25 (18) | 13.0 (8.5-17.6) | 0.412 |

| 25-30 (16) | 7.0 (3.2-10.8) | |

| ≥ 30 (18) | 4.0 (0.5-7.6) | |

| Surgery | ||

| Yes (21) | 10.23 (4.82-15.64) | 0.038 |

| No (34) | 8.7 (1.8-15.6) | |

| Type of surgery | ||

| Whipple (6) | 16.6 (0.0-39.4) | 0.988 |

| Hepatic lobectomy (6) | 10.2 (3.9-16.6) | |

| Bile duct excision (9) | 14.3 (8.5-20.1) | |

| Metastasis | ||

| Yes (19) | 7.07 (0.0-15.83) | 0.256 |

| No (36) | 9.09 (6.05-13.75) | |

| Stenting | ||

| Yes (24) | 9.9 (0.45-19.35) | 0.930 |

| No (32) | 9.16 (4.6-13.7) | |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes (14) | 16.96 (11.5-22.4) | 0.038 |

| No (41) | 6.2 (0-12.9) | |

| Chemotherapy in unresected patients | ||

| Yes (8) | 17 (12.76-21.18) | 0.001 |

| No (25) | 3.5 (1.12-5.8) | |

survival.

On univariate analysis, parameters that did influence survival included bilirubin level less than 10 mg/dL at presentation, surgical resection, and chemotherapy administration (Table 3). Since 49 out of 55 patients were stage IV, only these patients were included in Kaplan Meier survival (Figure 1) and multivariate analysis. Using Cox regression, a multivariate analysis was performed and only two were identified as independent predictors of increased survival: bilirubin level less than 10 mg/dL (Figure 1A) and chemotherapy administration (Figure 1B). Compared to patients with bilirubin levels less than 10 mg/dL, patients with higher bilirubin levels had a more than 2-fold increase in death risk from cholangiocarcinoma (P < 0.05). Although the risk of dying was less in patients who underwent surgery, results did not attain statistical significance. On the contrary, patients who received chemotherapy had better survival (P < 0.05, Table 4).

| Hazard’s ratio | 95% CI | P | |

| Bilirubin | |||

| < 10 | 1 | 1.13-0.52 | 0.023 |

| ≥ 10 | 2.421 | ||

| Surgery | |||

| No | 1 | 0.27-1.38 | 0.238 |

| Yes | 0.611 | ||

| Chemotherapy | |||

| No | 1 | 0.16-0.92 | 0.038 |

| Yes | 0.383 |

This is the first report of cholangiocarcinoma from Lebanon, a small country in the Middle East, with a population of 3.4 million people. Our study shows the positive impact of surgery, chemotherapy, and low bilirubin level on survival in patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma.

In previous studies, variables such as low preoperative bilirubin[4142829], radical resection[2829], negative resection margin[1130] and well-differentiated tumor histology[131] were found to be predictors of improved outcome. On the other hand, less-differentiated histology[32], perineural involvement, positive surgical margins, vascular or lymphatic invasion were associated with worse prognosis[3032–37].

The findings of our study emphasize the importance of increased bilirubin level upon presentation as an independent predictor of decreased survival in cholangio-carcinoma. Due to the small number of patients, we could not confirm the impact of the previously proposed variables on survival.

Radical surgery is considered as the most effective therapy for cholangiocarcinoma[5]. Only 20% of patients present with resectable disease[1]; yet surgery remains the only potential chance of cure. Without surgery, cholangiocarcinoma is a rapidly fatal disease with 5-year survival rates of less than 5%[9], while in curative resections 5-year survival approaches 20%-35% with negative surgical margins[5]. In our findings, we could not document an improved survival after surgical resection which can be explained by the advanced stage at which all patients presented and the small number of the study group.

The significance of chemotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma is still not clear especially with the low response rates[5], disappointing efficacy results and lack of a superior standard chemotherapeutic regimen[738]. Conflicting data exist regarding the role of chemotherapy in cholangiocarcinoma. Some studies suggest that chemotherapy, whether given in a setting of non-resectable disease or postoperatively, has little or no impact on the course of the disease or on survival outcome[13–152939–41] and is therefore considered palliative more than curative[42]. Other studies report survival benefit from chemotherapy[111243]. Recently, a pooled analysis of all clinical trials from 1985 to 2007 concluded that the combination of gemcitabine with oxaliplatin or cisplatin may improve survival in cholangiocarcinoma[10].

Our study adds further evidence to the previously published reports showing that chemotherapy improves survival in cholangiocarcinoma. We found that chemotherapy markedly improves survival in patients with either resected or unresected cholangiocarcinoma (17.0 mo vs 6.0 mo; P < 0.01). Additionally, chemotherapy prolonged survival significantly in patients with unresectable tumors (17.0 mo vs 3.5 mo; P = 0.001). Thus, in patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma who are not surgical candidates, Gemcitabine and/or 5-Fu based chemotherapy might offer a survival advantage.

Our results also show a non-significant decrease in survival with increasing BMI. The median survival for patients with BMI < 25 was 17.0 mo (8.5-17.6), 7.0 mo (3.2-10.8) for patients with BMI 25-29.99, and 4 mo (0.5-7.6) for patients with BMI ≥ 30 (P = 0.412). The fact that these results did not attain statistical significance may be attributed to the small sample size. Further prospective studies are needed to determine the effect of increased body mass index on prognosis in cholangiocarcinoma.

In line with other reports, cholangiocarcinoma in Lebanon affected older patients[4445] and more males than females[44–46], except in the above 70-year-old group where females were more commonly affected. However, the mean age of our patients was higher than that of patients in the USA[47]. The clinical symptoms and signs observed in Lebanese patients with cholangiocarcinoma were mostly of biliary obstruction and abdominal pain, as was previously reported[28].

Most of the tumors in our study were distal extrahepatic lesions, whereas perihilar lesions are the most common type usually reported[5648]. A moderate degree of differentiation was noted in the majority of tumors in our patients, while well-differentiated histology is more commonly reported[56].

Similar to other reports[4], this series did not identify any risk factors associated with cholangiocarcinoma, which is different from reports of biliary tract cancers elsewhere. In Asian countries, well-established risk factors are hepatolithiasis and liver fluke infestations[49], while in western countries hepatitis B and C infection, HIV, cirrhosis, diabetes, alcohol consumption, and IBD were recently implicated as potential risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma[444750].

Our patients might have had some of the known risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma that might have been missed at the time of patient presentation. Therefore, absence of those risk factors can not be ascertained due to the retrospective design of our study.

The prevalence of diabetes in our patients was 33% with the highest incidence being observed in patients over the age of 65, which was very close to the 29% prevalence rate of diabetes in the general Lebanese population older than 65 years[51]. Therefore, diabetes can not be considered a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma in our population, unlike other populations where diabetes increased the risk 2-3 folds[445052].

Cholelithiasis was present in 30% of our patients. Prevalence of cholelithaisis in cholangiocarcinoma patients was previously reported to fall in the 30% to 48% range[53]. It was described as a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma in a number of studies[505354]. However, a definitive cause-effect relationship has not been established yet.

Few reports addressed the association between BMI and bile duct cancer; Samonic et al showed that obese black men are at a significant risk of extrahepatic bile duct cancers[55]. On the other hand, Welzel et al showed that obesity was not a risk factor for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma[50]. Others suggested that increased body mass index was associated only with cancer of the extrahepatic duct[54]. Furthermore, in a large Korean cohort, a significant positive linear relationship was found between increasing BMI and risk of cholangiocarcinoma[56]. The risk of cholangiocarcinoma increased approximately 1.6 folds in patients with BMI > 30 kg/m2[56]. In our study, 68% of all patients with cholangiocarcinoma had excess BMI (median BMI was 26.9 kg/m2). In the Lebanese adult population, 53% are overweight (BMI ≥ 25), 17% are obese (BMI ≥ 30) and the mean BMI is estimated to be 25.9 kg/m2[26], which is comparable to the mean BMI of our study group.

There are several limitations in our study. The first is the small sample size, which is due to the rarity of the disease under investigation. Second, the study represents cases seen at a single tertiary care center, which may limit its utility in patients with cholangiocarcinoma in general. Third, our study is limited by its retrospective design; a key limitation resulting from such a design is the missing data, which may result in fewer patients included in multivariable models, generally increasing the risk for both type one and type two errors. Fourth, our study is non-randomized and lacks a control group. Despite the limitations of retrospective studies, absence of prospective and controlled data in the current literature makes the results of our study of more interest.

In conclusion, bilirubin levels less than 10 mg/dL at presentation and chemotherapy administration both in advanced disease and in postoperative adjuvant settings are associated with better prognosis and prolonged survival in patients with cholangiocarcinoma. None of the well-established or the potential risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma could be identified in the Lebanese population due to the above mentioned limitations. High body mass index was not found to be a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma; however, increments were associated with a trend towards a decrease in median survival.

Cholangiocarcinoma is an infrequent malignancy that involves the biliary epithelium. It has a poor prognosis with a survival less than 5% at five years. Radical surgery is the only potentially curative treatment modality, while the impact of chemotherapy on survival remains controversial. Due to small number of patients, determinants of prognosis in cholangiocarcinoma are not well characterized.

A retrospective review of the medical records of 55 patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma at the American University of Beirut between 1990 and 2005 was conducted. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to determine the impact of surgery, chemotherapy, body mass index, bilirubin level and other factors on survival.

Bilirubin levels less than 10 mg/dL at presentation and chemotherapy administration both in advanced disease and in postoperative adjuvant settings are associated with better prognosis and prolonged survival in patients with cholangiocarcinoma. High body mass index was not found to be a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma; however, increments were associated with a trend towards a decrease in median survival.

Palliative and postoperative chemotherapy as well as a bilirubin level < 10 mg/dL are independent predictors of a significant increase in survival in patients with cholangiocarcinoma. Large prospective controlled studies are needed to verify these results.

This article reports interesting epidemiological data on cholangiocarcinoma in Lebanon and the effects of surgical resection and chemotherapy on survival. Multivariate analysis identified only a bilirubin level < 10 mg/dL and chemotherapy as independent predictors of better survival.

| 1. | Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Gonen M, Burke EC, Bodniewicz BS J, Youssef BA M, Klimstra D, Blumgart LH. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507-517; discussion 517-519. |

| 2. | Vauthey JN, Blumgart LH. Recent advances in the management of cholangiocarcinomas. Semin Liver Dis. 1994;14:109-114. |

| 3. | Jarnagin WR, Shoup M. Surgical management of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:189-199. |

| 4. | Su CH, Tsay SH, Wu CC, Shyr YM, King KL, Lee CH, Lui WY, Liu TJ, P'eng FK. Factors influencing postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1996;223:384-394. |

| 5. | Patel T, Singh P. Cholangiocarcinoma: emerging approaches to a challenging cancer. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:317-323. |

| 6. | Malhi H, Gores GJ. Review article: the modern diagnosis and therapy of cholangiocarcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1287-1296. |

| 7. | Lee GW, Kang JH, Kim HG, Lee JS, Lee JS, Jang JS. Combination chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin as first-line treatment for immunohistochemically proven cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:127-131. |

| 8. | Khan SA, Taylor-Robinson SD, Toledano MB, Beck A, Elliott P, Thomas HC. Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours. J Hepatol. 2002;37:806-813. |

| 9. | Farley DR, Weaver AL, Nagorney DM. "Natural history" of unresected cholangiocarcinoma: patient outcome after noncurative intervention. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:425-429. |

| 10. | Eckel F, Schmid RM. Chemotherapy in advanced biliary tract carcinoma: a pooled analysis of clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:896-902. |

| 11. | Yoshida T, Matsumoto T, Sasaki A, Morii Y, Aramaki M, Kitano S. Prognostic factors after pancreatoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for distal bile duct cancer. Arch Surg. 2002;137:69-73. |

| 12. | Kelley ST, Bloomston M, Serafini F, Carey LC, Karl RC, Zervos E, Goldin S, Rosemurgy P, Rosemurgy AS. Cholangiocarcinoma: advocate an aggressive operative approach with adjuvant chemotherapy. Am Surg. 2004;70:743-748; discussion 748-749. |

| 13. | Takada T, Amano H, Yasuda H, Nimura Y, Matsushiro T, Kato H, Nagakawa T, Nakayama T. Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma? A phase III multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:1685-1695. |

| 14. | Yi B, Zhang BH, Zhang YJ, Jiang XQ, Zhang BH, Yu WL, Chen QB, Wu MC. Surgical procedure and prognosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2004;3:453-457. |

| 15. | Thongprasert S. The role of chemotherapy in cholangio-carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2005;16 Suppl 2:ii93-ii96. |

| 16. | Zhang J, Su XQ, Wu XJ, Liu YH, Wang H, Zong XN, Wang Y, Ji JF. Effect of body mass index on adenocarcinoma of gastric cardia. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2658-2661. |

| 17. | Parker AS, Lohse CM, Cheville JC, Thiel DD, Leibovich BC, Blute ML. Greater body mass index is associated with better pathologic features and improved outcome among patients treated surgically for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2006;68:741-746. |

| 18. | Wright JD, Powell MA, Mutch DG, Rader JS, Gibb RK, Gao F, Herzog TJ. Relationship of ovarian neoplasms and body mass index. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:595-602. |

| 19. | Enger SM, Greif JM, Polikoff J, Press M. Body weight correlates with mortality in early-stage breast cancer. Arch Surg. 2004;139:954-958; discussion 958-960. |

| 20. | Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625-1638. |

| 21. | Lee J, Wang H, Chia KS, Koh D, Hughes K. The effect of being overweight on cancer incidence and all-cause mortality in Asians: a prospective study in Singapore. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:875-876. |

| 22. | Wolk A, Gridley G, Svensson M, Nyren O, McLaughlin JK, Fraumeni JF, Adam HO. A prospective study of obesity and cancer risk (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:13-21. |

| 23. | Bergstrom A, Pisani P, Tenet V, Wolk A, Adami HO. Overweight as an avoidable cause of cancer in Europe. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:421-430. |

| 24. | Zatonski WA, Lowenfels AB, Boyle P, Maisonneuve P, Bueno de Mesquita HB, Ghadirian P, Jain M, Przewozniak K, Baghurst P, Moerman CJ. Epidemiologic aspects of gallbladder cancer: a case-control study of the SEARCH Program of the International Agency for Research on Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1132-1138. |

| 25. | American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual. Springer: Philadelphia 2002; 145-150. |

| 26. | Sibai AM, Hwalla N, Adra N, Rahal B. Prevalence and covariates of obesity in Lebanon: findings from the first epidemiological study. Obes Res. 2003;11:1353-1361. |

| 27. | Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i-xii, 1-253. |

| 28. | Zhang BH, Cheng QB, Luo XJ, Zhang YJ, Jiang XQ, Zhang BH, Yi B, Yu WL, Wu MC. Surgical therapy for hiliar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of 198 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:278-282. |

| 29. | Cheng Q, Luo X, Zhang B, Jiang X, Yi B, Wu M. Predictive factors for prognosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: postresection radiotherapy improves survival. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:202-207. |

| 30. | Silva MA, Tekin K, Aytekin F, Bramhall SR, Buckels JA, Mirza DF. Surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma; a 10 year experience of a tertiary referral centre in the UK. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:533-539. |

| 31. | Todoroki T. Chemotherapy for bile duct carcinoma in the light of adjuvant chemotherapy to surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:644-649. |

| 32. | Kawarada Y, Yamagiwa K, Das BC. Analysis of the relationships between clinicopathologic factors and survival time in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2002;183:679-685. |

| 33. | Harrison LE, Fong Y, Klimstra DS, Zee SY, Blumgart LH. Surgical treatment of 32 patients with peripheral intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1068-1070. |

| 34. | Hanazaki K, Kajikawa S, Shimozawa N, Shimada K, Hiraguri M, Koide N, Adachi W, Amano J. Prognostic factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after hepatic resection: univariate and multivariate analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:311-316. |

| 35. | Havlik R, Sbisa E, Tullo A, Kelly MD, Mitry RR, Jiao LR, Mansour MR, Honda K, Habib NA. Results of resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma with analysis of prognostic factors. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:927-931. |

| 36. | Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Ohge H, Sueda T. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and surgical margin status for distal cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:207-212. |

| 37. | Ramacciato G, Di Benedetto F, Cautero N, Masetti M, Mercantini P, Corigliano N, Nigri G, Lauro A, Ercolani G, Del Gaudio M. [Prognostic factors and long term outcome after surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Univariate and multivariate analysis]. Chir Ital. 2004;56:749-759. |

| 38. | Malka D, Boige V, Dromain C, Debaere T, Pocard M, Ducreux M. Biliary tract neoplasms: update 2003. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16:364-371. |

| 39. | Mazhar D, Stebbing J, Bower M. Chemotherapy for advanced cholangiocarcinoma: what is standard treatment? Future Oncol. 2006;2:509-514. |

| 40. | Takada T, Nimura Y, Katoh H, Nagakawa T, Nakayama T, Matsushiro T, Amano H, Wada K. Prospective randomized trial of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and mitomycin C for non-resectable pancreatic and biliary carcinoma: multicenter randomized trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:2020-2026. |

| 41. | Nakeeb A, Pitt HA. Radiation therapy, chemotherapy and chemoradiation in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2005;7:278-282. |

| 42. | Price P. Cholangiocarcinoma and the role of radiation and chemotherapy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:51-52. |

| 43. | Glimelius B, Hoffman K, Sjoden PO, Jacobsson G, Sellstrom H, Enander LK, Linno T, Svensson C. Chemotherapy improves survival and quality of life in advanced pancreatic and biliary cancer. Ann Oncol. 1996;7:593-600. |

| 44. | Shaib YH, El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Morgan R, McGlynn KA. Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a case-control study. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:620-626. |

| 45. | Liu XF, Zhou XT, Zou SQ. An analysis of 680 cases of cholangiocarcinoma from 8 hospitals. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4:585-588. |

| 46. | Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1655-1667. |

| 47. | Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463-473; discussion 473-475. |

| 49. | Shaib YH, El-Serag HB, Nooka AK, Thomas M, Brown TD, Patt YZ, Hassan MM. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a hospital-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1016-1021. |

| 50. | Welzel TM, Mellemkjaer L, Gloria G, Sakoda LC, Hsing AW, El Ghormli L, Olsen JH, McGlynn KA. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in a low-risk population: a nationwide case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:638-641. |

| 51. | Salti IS, Khogali M, Alam S, Nassar , N , Abu Haidar N, Masri A. The epidemiology of diabetes mellitus in relation to other cardiovascular risk factors in Lebanon. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 1997;3:462-471. |

| 52. | Wideroff L, Gridley G, Mellemkjaer L, Chow WH, Linet M, Keehn S, Borch-Johnsen K, Olsen JH. Cancer incidence in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized with diabetes mellitus in Denmark. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1360-1365. |

| 53. | Khan ZR, Neugut AI, Ahsan H, Chabot JA. Risk factors for biliary tract cancers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:149-152. |

| 54. | Chow WH, McLaughlin JK, Menck HR, Mack TM. Risk factors for extrahepatic bile duct cancers: Los Angeles County, California (USA). Cancer Causes Control. 1994;5:267-272. |

| 55. | Samanic C, Chow WH, Gridley G, Jarvholm B, Fraumeni JF Jr. Relation of body mass index to cancer risk in 362,552 Swedish men. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:901-909. |

| 56. | Oh SW, Yoon YS, Shin SA. Effects of excess weight on cancer incidences depending on cancer sites and histologic findings among men: Korea National Health Insurance Corporation Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4742-4754. |