INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) is an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory disorder of the intestines with no known cure. Traditionally, the principal goal of treatment has been symptom control. Upon diagnosis, patients are usually started on medications based on the severity of the presenting symptoms. Patients with mild or moderate symptoms are often started on medications such as 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASA) or antibiotics. Though the efficacy of mesalamine is limited in CD[1], therapy with mesalamine is initiated because of its minimal toxicity and excellent safety profile. For sicker patients, physicians often initiate therapy with corticosteroids, because of their superior ability to control symptoms[2]. In this setting, the short-term toxicities of steroids are tolerated with the hope that the patient will enter a durable symptomatic remission and stop steroid therapy before any long-term steroid-related complications develop. Therapy with the immunomodulators, azathioprine (AZA) or methotrexate, or biological agents, such as infliximab or adalimumab, is reserved for patients who either fail to respond to steroids or fail to enter a steroid free remission. Despite the recognized efficacy of the immunomodulators and biological agents to both induce and maintain remission in CD[34], early use of these drugs is tempered by the fear of their complications, such as life threatening infections or malignancy. Symptom abatement with the least toxic drug regimen is the guiding principle of this type of “step-up” approach to the management of CD. However, recent studies and emerging expert opinion have begun to question these traditional treatment goals and approaches[56].

Not only can medical therapies lead to symptom control, but they may actually alter the natural history of CD by reducing the rates of surgery, hospitalizations and disability. In fact, using “aggressive” therapy earlier in the disease course, i.e. immunomodulators and/or biological agents, may be the best approach to prevent irreversible damage to the bowel. Currently, this relationship between medical therapy, mucosal healing and improved clinical outcomes is being investigated. Standard “step-up” therapies fail to induce mucosal healing in many patients, and the overall morbidity, and even mortality, of Crohn’s patients may be reduced by a more timely use of immunomodulators and biological agents[6–8]. This treatment paradigm in which immunomodulators and/or biological agents are used immediately in newly diagnosed Crohn’s patients to induce a rapid remission has been labeled the “top-down” approach. Once remission has been achieved, an attempt is made to reduce the maintenance therapy to the medications with the least presumed toxicity. The more potent medications are used again if the patient flares, on an on-demand basis. However, for many patients, tapering down these therapies may not be possible, or even prudent to try. Therefore, it is unclear if a top-down approach is practical; perhaps the optimal treatment approach is actually “top and STAY PUT”.

Ultimately, we must weigh the safety and efficacy of the therapies with the risks of the disease itself. The purpose of this paper is to review the data regarding the differing treatment approaches to CD and to synthesize these data into an optimal treatment approach circa 2008.

NATURAL HISTORY OF CD

The natural history of CD remains poor for many, if not most, patients. Symptomatic flares, leading to reduced quality of life, are inevitable for almost all patients over a ten year period[9]. Steroid use is common, often incompletely effective, and is associated with many side-effects and complications[10]. For most patients there is an inexorable progression of bowel injury culminating in the need for intestinal resection in upwards of 80% of patients during their lifetime[1112]. Hospitalization and surgery account for the majority of the direct cost of caring for patients with CD[1314]. Unfortunately, surgery is not curative, with endoscopic recurrence in 75% of patients at 1 year after surgery, and symptomatic recurrence in 50% of patients at 5 years[15].

WHAT SHOULD BE THE GOALS OF THERAPY: SYMPTOM CONTROL OR MUCOSAL HEALING?

The traditional goal of therapy in CD in the clinical setting has been relief of symptoms, such as abdominal pain and diarrhea, with restoration of a general sense of well-being. In research studies, the CD Activity Index (CDAI) has been used to define treatment responses and remission. However, many of the factors in the CDAI are considered subjective measures of patient symptoms, and more objective therapeutic endpoints, such as mucosal healing, are being evaluated.

The major morbidity from CD is a result of uncontrolled inflammation of the intestines and perianal area, leading to ulceration. Intestinal ulceration can lead to bleeding and anemia, perforation with abscess or fistula formation, or subsequent fibrosis with obstruction. Presumably, if the mucosa is healed, then these complications cannot occur. Interestingly, there appears to be a disconnect in CD between symptoms and mucosal healing. For example, in the endoscopic substudy of A Crohn's Disease Clinical Trial Evaluating Infliximab in a New Long-Term Treatment RegimenI(ACCENTI), mucosal healing did not correlate with CDAI. At 10 wk, only 36% of patients with mucosal healing were in remission as defined by the CDAI, and 40% of patients in clinical remission by CDAI did not have endoscopic remission[16]. So what is the optimal endpoint of therapy in CD? Ideally, patients should feel well, but should they also be treated to reduce intestinal injury in the hope of reducing the need for surgery?

Symptom control may not be enough, but unfortunately there is still no definite evidence that pushing therapy to achieve mucosal healing modifies the natural history of CD, though there are emerging data that this may be the case. In the postoperative setting, seminal work by Rutgeerts and colleagues has demonstrated that endoscopic recurrence precedes and predicts clinical recurrence[15]. Patients with no or very mild lesions (few aphthous ulcers) at follow-up endoscopy one year after resection had a low risk of endoscopic progression or clinical recurrence, with clinical recurrence rates remaining less than 10% over 5-10 years of follow-up. However, patients with advanced lesions (diffusely inflamed mucosa or worse) seen at follow-up endoscopy one year after resection had a poor prognosis with further endoscopic progression and clinical recurrence occurring in upwards of 90% over time[15]. In the ACCENT I study, patients on maintenance infliximab with mucosal healing required fewer hospitalizations and surgical interventions[17]. Nine patients had evidence of mucosal healing at both 10 wk and 54 wk endoscopic evaluations, and no CD related hospitalizations were required in this group. Patients with evidence of mucosal healing at 1 visit (either 10 wk or 54 wk) required fewer CD related hospitalizations as compared to patients with no healing at either visit (18.8% vs 28%)[16]. In a Norwegian population-based cohort, mucosal healing after one year of treatment was associated with decreased disease activity during the follow-up period and decreased need for active treatment over five years[18].

Though the data to support mucosal healing as the optimal endpoint for CD therapies remains scant, one could argue that the reason we have not yet seen a change in the natural history of CD in the general population is because according to our standard treatment approaches, we are only using drugs with a good potential to heal mucosa, such as the immunomodulators or biological agents, on the most refractory patients. Often, this is when the chronic inflammation of the bowel has already led to irreversible injury, manifest as high-grade strictures or bowel perforation with abscess or fistula formation. These complications may be beyond the capacity of any medicine to rectify.

TO WHAT EXTENT DO THE CURRENT THERAPIES ACHIEVE THESE GOALS OF TREATMENTS?

First line therapies often include treatment with 5ASA or antibiotics as these are presumed to have low or limited toxicity. However, multiple studies have failed to demonstrate robust clinical efficacy for 5-ASA agents, particularly in patients with small bowel or ileocolic disease[1219]. Limited data exist on the efficacy of antibiotics, as well. But, the use of antibiotics in CD has been poorly studied[20]. pH release formulations of budesonide (Entocort), a corticosteroid with limited systemic bioavailability, and therefore, less short term side-effects than prednisone, can be used to induce remission in right sided colonic and ileal disease, but at 1 year is unlikely to maintain remission[2122]. For moderate to severe disease activity, systemic corticosteroids, such as prednisone, are often used, but are known to have significant short and long-term side effects. In addition, studies indicate that although steroids are effective at suppressing acute inflammation quickly, they have shown no benefit in maintaining a remission, preventing new flares or inducing mucosal healing[23]. Population based studies from Olmstead County have shown that 43% of CD patients required treatment with steroids; of these, the majority (85%) were able to achieve complete or partial response at one mo. However, at one year only one-third of patients had a sustained response: 28% patients were steroid dependent and 38% patients required surgical intervention[10]. In addition, less than one third of patients in a clinical remission on steroids had evidence of mucosal healing at 7 wk[24]. Steroids may also worsen disease, especially in patients with fistula, leading to higher rates of abscess formation and sepsis[25].

Immunomodulators, such as azathioprine (AZA) or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), have a slow onset of action in CD, so their utility for the rapid induction of remission is limited[26]; however, they have been shown to maintain a remission in CD, and are able to induce mucosal healing[8]. Treatment with AZA/6MP results in an approximately 40% steroid-free remission rate at 1 year[27]. A study of 20 patients with Crohn’s colitis or ileocolitis treated with azathioprine demonstrated that in the colon, 70% of patients had complete mucosal healing, while in the ileum, 54% had complete healing[28]. Even with their demonstrated ability to heal mucosa and be steroid sparing in CD, Cosnes et al did not find a decrease in rates of operations for Crohn’s over the past two decades, despite an increased use of AZA/6-MP over this time period[29]. One major caveat to this finding is that the majority of patients on immunosuppression were on therapy for less than 3 mo prior to their operation, which is often too short a treatment period to expect any real benefit from immunomodulators. Studies from the pediatric literature suggest that immunomodulators can have longstanding effects on CD that may alter the natural history. In one randomized controlled trial of children aged 13 (+/-2) years with moderate to severe CD on steroids and within 8 wk of CD diagnosis, immunomodulator use was able to induce a durable steroid-free remission, with a long term remission rate of 89% at 18 mo[30].

The data is even more compelling for infliximab, an anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agent. In ACCENT I, regularly scheduled infusions of infliximab led to superior remission and response rates, superior mucosal healing, and decreased need for hospitalizations and surgery compared with placebo or episodic infusions of infliximab[17]. In the scheduled treatment group, 31% of patients had evidence of complete mucosal healing at 10 wk and 50% of patients had complete mucosal healing at wk 54[16]. Currently, these medications are often reserved for patients who are steroid refractory or steroid dependent, who are either not responding or too sick to wait for the effects of immunomodulators. The main reason for reserving anti-TNF therapy for sicker patients is the presumed risk-benefit profile.

DOES TOP-DOWN THERAPY EXPOSE PATIENTS TO AN INCREASED RISK OF MEDICATION-RELATED COMPLICATIONS? THE RATIONALE FOR STEP-UP THERAPY

A small number of CD patient’s will have a very mild course, requiring only treatment with 5-ASAs, antibiotics or a short course of budesonide, without further need for systemic steroids or immunomodulators. A top-down approach would unnecessarily expose these patients to the side effects of the immunomodulators and biologics. Immunomodulator use has been associated with an increased risk of infection, hepatitis, bone marrow suppression, pancreatitis and lymphoma[31]. Two to five percent of patients will experience bone marrow suppression secondary to azathioprine/6MP, and even in the absence of leukopenia, there is a risk of serious infection[4]. A recent meta-analysis suggests a four-fold increased risk of lymphoma in IBD patients treated with azathioprine/6-MP[32]. Side effects of the biologics can include infectious complications, malignancy, demyelinating disorders, autoimmunity and worsening of CHF[3]. Anti-TNF agents are associated with a 2.8%-4% increased risk of serious infections[3]. Analysis of the Crohn’s Therapy, Resource, Evaluation and Assessment Tool (TREAT) registry demonstrated a relative risk of lymphoproliferative disorders of 1.3[14]. Recently, the risk of a rare form of lymphoma, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, has been seen in association with infliximab and concomitant immunomodulator use. This type of lymphoma predominantly affects patients age 10-30 (the oldest reported patient is 31), and has not been seen in patients on infliximab alone[33]. This list of serious and potentially life-threatening side effects has resulted in the limited use of biologic therapy to only the most severe cases of CD, which are resistant to conventional therapies. The recent American Gastroenterological Society (AGA) technical review on corticosteroids, immunomodulators and infliximab in IBD specifies that current indications for infliximab include severely active CD resistant to medical therapy or intolerant of medical therapy[4].

Given these potential toxicities, a recent decision analysis evaluated the risks and benefits of infliximab as compared to standard therapy. This model suggested that despite an increased risk of lymphoma and death, infliximab results in increased quality of life years secondary to clinical response and remission rates and decreased surgical rates, and in properly selected patients, the benefits outweigh the risks[7]. The modeling likely underestimated the response and remission rates, and overestimated the mortality rates as data from the TREAT registry were excluded[34]. Interestingly, analysis of the TREAT registry revealed that infliximab, in multivariate, logistic regression analysis, was not an independent predictor of serious infections. Factors independently associated with serious infection included prednisone use, narcotic analgesic use, and moderate to severe disease activity. No increased risk of malignancy was associated with infliximab use, and the only factor associated with increased mortality was use of prednisone[14]. It is important to note that exposure to prednisone is likely greater over time with the step-up treatment approach.

CAN THE TIMING AND ORDER OF MEDICINES CHANGE THE NATURAL HISTORY OF CD? THE RATIONALE FOR TOP-DOWN THERAPY

Studies in the pediatric population suggest that early treatment may alter the course of CD, and response to therapy may be related to disease duration. In a prospective, placebo controlled trial of newly diagnosed pediatric CD patients with moderate to severe disease on steroids, early (within 8 wk of initial diagnosis) treatment with 6-MP resulted in a 85% sustained steroid-free remission as compared to 54% of patients receiving placebo[30]. In a small study of 15 patients, Kugathesan et al treated 15 children with medically refractory CD in a prospective, open-label trial of a single, 5 mg/kg infliximab infusion. Fourteen of fifteen children responded. Of the 14 patients who responded, six had early CD (< 2 years from time of diagnosis) and eight had late CD (> 2 years from time of diagnosis). Three of six children with early disease maintained clinical response through the 12-mo trial period, compared to none of the eight children with late disease[35]. What is most remarkable about this study is that a single infusion of infliximab was able to induce such a profound and prolonged clinical response. This was a small study, but the positive findings suggest that there is something different about the newly presenting CD patient versus the relapsing/remitting CD patient. Based on this and other studies, there has been some speculation that earlier in the disease, medications such as infliximab may be able to change the natural history of CD.

In the REACH (Response and Remission Related to Infliximab in Pediatric Patients with Moderate to Severe CD) trial, pediatric patients on concurrent immunomodulators, with mean disease duration of only 1.6 years, were given an infliximab induction regimen. Responders were randomized to infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 wk or every 12 wk. At 10 wk there was an 88% clinical response and 59% clinical remission rate. At 54 wk, subjects receiving every 8 wk infliximab had a 64% response rate and 56% remission rate[36]. These response and remission rates are superior to those seen in ACCENTIstudy of infliximab in adults with a median disease duration of > 7 years, where the 10 wk remission rate was 40% and 54 wk remission rate was 30%[17].

Retrospective analysis of data from Pegylated Antibody Fragment Evaluation in Crohn’s Disease Safety and Efficacy 2 (PRECiSE 2) and Crohn’s trial of the fully Human antibody Adalimumab for Remission Maintenance (CHARM) have demonstrated similar results. In PRECiSE 2, a higher percentage of patients were able to achieve a clinical response or remission with monthly certolizumab if they had < 1 year of disease activity versus those who had a longer duration of disease (> 2 years)[37]. A subanalysis of the CHARM study presented at DDW 2007 evaluated patients who responded to treatment with adalimumab at a 4 wk evaluation, and randomized these wk-4 responders to a maintenance regimen of placebo, adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous weekly or adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous every other week. In logistic regression analysis controlling for age, gender, CRP, concomitant therapies, presence of fistulas and active treatment with adalimumab, patients with disease duration of less than 2 years achieved the highest remission rates, confirming that disease duration had a significant effect on ability to achieve and maintain a remission[38].

The potential for biologics to induce mucosal healing and potentially change the natural history of CD has been further illustrated by the Top Down/Step Up trial, which is currently awaiting publication, but has been presented in abstract form at DDW 2006[3940]. This is an open-label, multicenter trial in 26 centers in the Netherlands and Belgium. Patients with active CD of less than 4 years duration were eligible for enrollment. Subjects were randomized to a top-down arm (infliximab induction 0, 2, 6 wk with AZA maintenance, with on-demand infliximab for flares; systemic steroids were added only if patients did not respond to the combination of infliximab and AZA) or a step-up arm (Prednisone 40 mg daily; permitted 2 steroid tapers before starting AZA; and then infliximab if failed treatment with immunomodulators). Co-primary endpoints were steroid-free remission and need for surgery at 6 and 12 mo. All patients underwent endoscopy at baseline with blinded scoring of ulcers. At 6 and 12 mo, significantly more top-down patients were in a steroid-free remission without resection as compared to the step-up arm (60% vs 36% at 6 mo, 62% vs 42% at 12 mo). At 24 mo, no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups. The most remarkable finding in this cohort was the results of the endoscopic substudy, in which 44 patients were evaluated at 2 years after study initiation. 71% (17/24) of patients in the top-down arm achieved mucosal healing versus 30% (6/20) in the step-up arm. Some of the patients in the top-down arm had only received an induction dose of infliximab[3940].

Why might earlier use of immunomodulators or biological drugs lead to better long-term outcomes in CD? Later exposure to these potent therapies may be less effective because irreversible bowel injury may have occurred, with transformation of an inflammatory phenotype to a stricturing or penetrating phenotype, which is beyond the ability of medical therapy to repair. Alternatively, the immune dysregulation may be more difficult to reverse in long-standing disease, maybe more so in patients previously exposed to corticosteroids[41].

ONCE YOU START BIOLOGICAL THERAPY, CAN YOU EVER STOP IT? IS THE NOTION OF TOP-DOWN THERAPY A MYTH?

The idea of top-down therapy would be more palatable if many patients exposed to these more potent, but potentially toxic therapies can have these treatments tapered or discontinued over time. However, it is not clear if this is possible for many patients. ACCENT I data clearly support the use of scheduled infliximab therapy as compared to episodic therapy[17], and this has become the standard of care when treating with infliximab. In the Top Down/Step Up trial, patients randomized to the Top-Down arm were given infliximab as induction therapy, and maintained with immunomodulators. Infliximab was given on-demand for symptom relapse[40]. Practically, it is rare for practitioners to use biologic agents as a bridge to other therapies or to use biologics episodically. Is a top-down approach realistic, or is it really a top and stay therapy?

Infliximab has been evaluated as a bridge to azathioprine therapy in steroid-dependent CD[42]. Patients received an induction regimen of infliximab or placebo, and all patients were given either Azathioprine or 6 MP; relapse was treated with steroids. At 52 wk, 40% of patients receiving infliximab induction followed by AZA/6MP were in a steroid-free remission as compared to 22% of patients who received placebo and then AZA/6MP. Although there is a statistically significant difference favoring induction with infliximab, a gradual loss of efficacy was seen when compared to the wk 12 steroid-free remission rates: 75% in the infliximab group and 38% in the placebo group[42].

Data from the Step-Up/Top-Down trial also indicate that a substantial proportion of patients started on biologics have to remain on them. At one year, 41% of patients in the Top-Down group required at least one additional dose of infliximab , with a median interval of infusion of 16 wk[40].

The association of combination infliximab and immunomodulator use (specifically AZA/6MP) with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma[33] has led many practitioners to move towards monotherapy, but most clinicians are choosing biologic monotherapy over immunomodulator monotherapy. Initial results from the Infliximab Maintenance Immunosupression Discontinuation (IMID) trial demonstrated no clinically significant benefit of combined therapy with infliximab and immunomodulator as compared to infliximab alone[43]. Patients in clinical remission on combination infliximab and immunomodulator (AZA/6MP) therapy were randomized to continue or discontinue immunomodulators after at least 6 mo of concomitant therapy. There was no difference in percent of patients requiring a change in infliximab dosing or discontinuation of infliximab therapy due to loss of response or intolerance between the two groups, and no difference in mucosal healing rates (61% in combination therapy group and 67% in infliximab monotherapy group). The only significant findings were that patients on combination therapy had higher median infliximab levels, higher trough serum infliximab levels, and lower incidence of antibodies to infliximab, although the clinical significance of these findings was unclear[43]. Additionally, data from ACCENT I and CHARM did not show any difference in remission rates with or without concomitant immunomodulator therapy at one year[4445].

IS ONE TREATMENT PARADIGM APPROPRIATE FOR ALL CROHN’S PATIENTS?

A proportion of patients will have only very mild disease activity, and some may never have a flare requiring treatment with steroids. How do we differentiate patients who will never have a progressive, complicating disease course, in order to avoid the unnecessary exposure and the increased expense that would be associated with a top-down strategy? Ideally, we would apply a top-down approach to the subset of patients with the most aggressive disease, before the disease may become more resistant to treatment with biologics.

A retrospective study of 1123 CD patients at a tertiary referral center found a disabling disease course in 85% patients over 5 years of follow-up[46]. Disabling disease course was defined as greater than 2 steroid courses or steroid-dependence, hospitalizations, disabling chronic symptoms, need for immunosuppressive treatment, and intestinal resection or surgery for perianal disease. Clinical factors associated with a disabling disease course included: young age at onset of disease, presence of perianal lesions, early need for systemic steroids, and isolated small bowel involvement[46]. A second retrospective, cohort study of 83 patients undergoing surgery within the first three years of CD diagnosis found that smoking, isolated ileal involvement and oral corticosteroid use within the first 6 mo of diagnosis were associated with an increased risk of surgery[47]. Additional prognostic information may be attained from evaluation of serum markers such as ASCA, anti-OmpC, Anti-CBir1 and anti-I2. In a prospective study of 196 pediatric patients, the frequency of internal penetrating and/or stricturing disease increased with the number of positive markers, and the odds of developing internal penetrating and/or stricturing disease was highest in patients with all four immune markers[48]. Genetic markers show promise; CARD15 mutations are thought to be responsible for approximately 20% of the genetic predisposition to CD[49].

Ultimately, our ability to risk stratify patients remains crude. There is an urgent need for the ability to assess prognosis at the time of diagnosis, in order to personalize treatment options by targeting the patients who are at greatest risk of progressing to complicated disease with earlier, more potent anti-inflammatory therapy.

MAKING PRACTICAL SENSE OF THE TREATMENT PARADIGMS: HOW MIGHT THEY BE IMPLEMENTED?

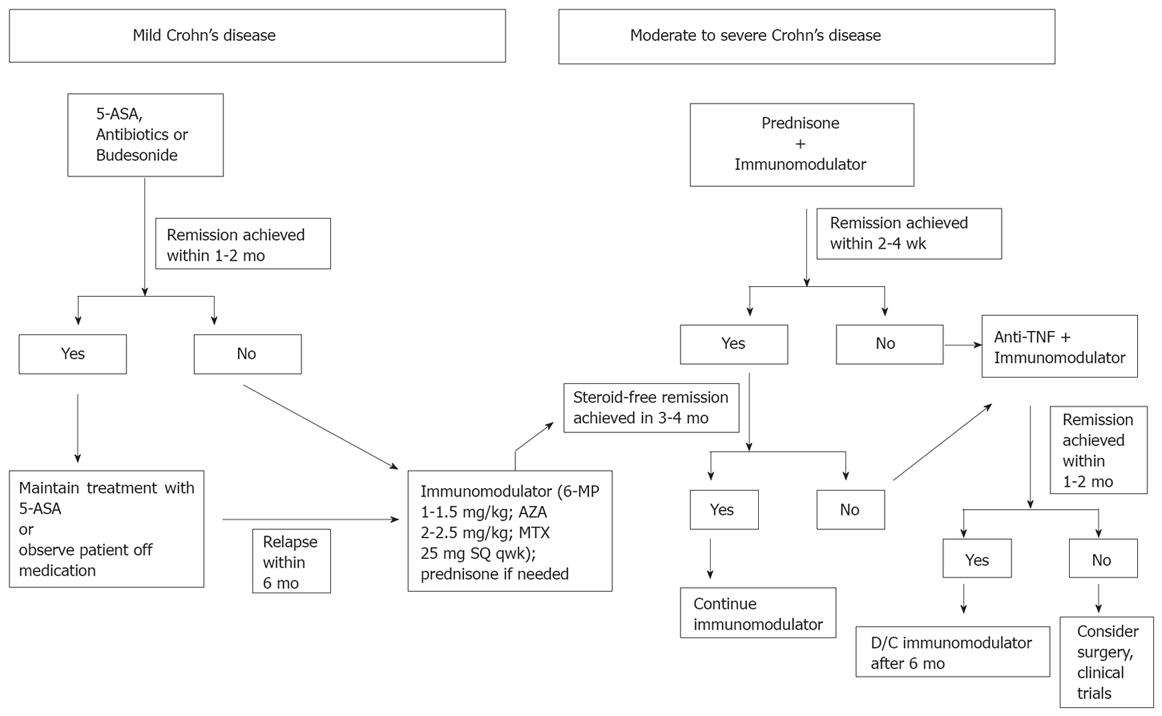

For now it seems that both the step-up and top-down treatment approaches, as they are conventionally defined, are lacking for many patients. It does not make sense to attempt to treat patients with severe symptoms at presentation with mesalamine, nor does it make sense to allow two attempts at a steroid taper before escalating therapy to an immunomodulator, as was done in Hommes’ StepIUp/Top-Down study. At the same time, it makes little sense to expose all newly diagnosed patients to treatment with a biological drug, and it is increasingly unclear if patients treated with a biological drug should be treated concurrently with an immunomodulator. Based on the current data, we believe that a hybrid treatment approach, one that still “steps-up” therapy, but does so aggressively, is best. This approach can be described as an “accelerated” step-up strategy (Figure 1).

Figure 1 “Accelerated” step-up treatment algorithm.

The accelerated step-up treatment approach preserves the tactic of matching disease severity with treatment potency, but keeps in mind that earlier use of these potent therapies may have better outcomes. For patients with mild presenting symptoms, we still seek to achieve remission with mesalamine, antibiotics or budesonide. If remission is achieved within 1-2 mo, then options are to attempt to maintain remission with mesalamine, or observe the patient off medications. If the initial remission is not achieved within this short period of time, or for patients who relapse within 6 mo, therapy is started with an immunomodulator (6-MP with target dose of 1-1.5 mg/kg per day, AZA with target dose of 2-2.5 mg/kg per day or MTX with dose of 25 mg sq per week). Therapy with prednisone is initiated for patients with moderate or severe symptoms that do not permit one to wait the 2-4 mo required for the immunomodulators to take effect, though steroid use is avoided in patients with known perforating/fistulizing disease. Patients started on an immunomodulator are expected to be in a steroid free remission within 3-4 mo. For those that do not achieve this goal within that time frame, therapy with one of the anti-TNF drugs is initiated. At the present time, therapy with the immunomodulator is continued at the outset of therapy with a biological agent, but once the patient enters remission, concomitant therapy with the immunomodulator is stopped in most cases. For patients receiving infliximab infusions, intravenous hydrocortisone 200 mg is given as a premedication.

Biologics, i.e. anti-TNF drugs, are started even earlier if steroids are not able to induce a remission within 2-4 wk, if a patient is intolerant of steroids or if a patient is intolerant of an immunomodulator. In addition, steroids are not used at all in patients with fistulizing or perforating disease, even at the outset. These patients are treated immediately with antibiotics, and in all but the mildest cases, one of the immunomodulators. If the patient is too ill to wait for the immunomodulators to take effect, then therapy is initiated immediately with a biological drug. In all cases therapy with immunomodulators and/or biological agents is not initiated until it is clear there is no infection that requires therapy and there is no indication for immediate operative intervention. With all of these therapies, the treatment endpoint remains symptom resolution. Though the authors concede the potential importance of mucosal healing in addition to symptom relief as a treatment goal, the authors do not yet document mucosal healing in all patients, nor do they push therapy in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients if persistent inflammation is seen on endoscopy or imaging studies.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The ideal treatment approach in CD remains uncertain, as does the optimal endpoint of therapy. Since CD is heterogeneous with respect to phenotype and severity, it is unlikely that one approach will be best for all patients. Nevertheless, it is the authors’ opinion that many physicians are not aggressive enough with therapy, delaying the use of potentially disease-modifying agents, such as the immunomodulators and/or biological agents, in patients with moderated to severe CD. In addition, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests that mucosal healing, which is most rapidly achieved with biologic therapy, is an appropriate treatment endpoint in CD patients. It does appear that earlier therapy with biologic drugs results in an increased response to therapy. Although no clear prospective study has been able to show that either mucosal healing or early biologic therapy are associated with a long-term change in the natural history of CD, there is a documented association with decreased hospitalizations and decreased need for surgery over one year of therapy. The greatest burden of CD comes from hospitalizations and surgeries, and thus early, aggressive therapy may have improved outcomes at an individual as well as a societal level. For now the authors recommend the “accelerated step-up” approach to therapy as outline above as the best way to induce and maintain CD remission while minimizing the risk of unnecessary medication toxicities. What is urgently needed are studies to improve the ability of clinicians to risk stratify patients upon diagnosis, and to predict response to therapies, so that treatment approaches can be individualized and optimized. Additional studies also are needed to demonstrate conclusively that mucosal healing, in addition to symptom control, should be a primary goal of therapy in CD.

Peer reviewers: General Surgery, University of South Florida

College of Medicine, 21st Century Oncology Chair in Colorectal

Surgery, Chairman Department of Colorectal Surgery, Chief of

Staff, Cleveland Clinic Florida, 2950 Cleveland Clinic Boulevard,

Weston, Florida 33331, United States; Rainer J Duchmann,

Professor, Medizinische Klinik I, Campus Benjamin Franklin,

Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Hindenburgdamm 30,

D-12200 Berlin, Germany