CASE REPORT

A 20-year-old female had a history of itching in arms and legs which began in February 2005. She had no fever, diarrhea, weight loss, hematuria, vision problems, or headache. Anti-allergic medications did not show any favorable effects on the symptoms. Meanwhile, multiple reddish-brown macular lesions developed on her heels spreading upwards to legs and buttocks. She was treated with oral prednisolone at a dose of 20 mg/d. Although old lesions seemed to subside following treatment, new lesions appeared on the back, neck, and arms. Light brown macular lesions united to form plaque-like non-blanching lesions with erythema at the center. Skin biopsy was consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Figure 1A and B demonstrate the histologic characteristics of the skin biopsy specimen. Although, the dose of prednisolone was increased to 40 mg/d, she did not respond to it, thus, it was discontinued.

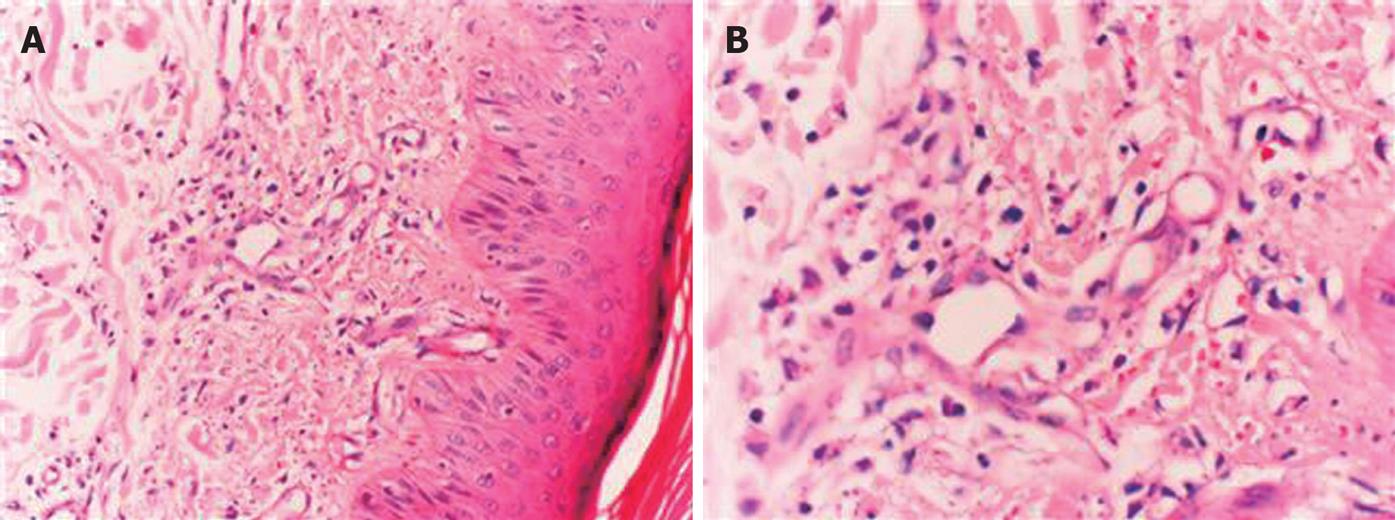

Figure 1 Skin biopsy specimen (HE, × 200) showing polymor-phonuclear cells and lymphocyte infiltration in and around the vessels of dermis beneath the multilayered keratinized squamous epithelium with some nuclear debris in the interstitium (A) and fibrin deposits in the vessel wall and nuclear debris (B).

She was admitted to our clinic with the complaint of bloody diarrhea in September 2005, eight months after the first appearance of skin lesions. She reported that she passed bloody stool containing mucus, 8-10 times a day. Apart from the scars of old lesions and new light-brown macular lesions around the ankles, physical examination yielded normal results. Results of the laboratory investigations included the followings: 9.870/mm3 white blood cells, 10.6 g/dL hemoglobin, 72 fL MCV, 409.800/mm3 platelets. Peripheral blood smear showed hypochromia, microcytosis and anisocytosis, 29 mm/h of erythtrocyte sedimentation rate, 34 C-reactive proteins, 75 U/L ALT (normal: 0-50 U/L), 64 U/L AST (normal: 0-40 U/L), 159 U/L ALP (normal: 40-150 U/L), 272 U/L GGT (normal: 5-64 U/L), and 0.81 mg/dL total bilirubin (normal: 0.2-1.2 mg/dL). Urine analysis was normal. Blood fasting glucose, urea, creatinine, total protein, albumin levels and electrolyte (albumin, sodium, potassium, chloride, and calcium) concentration were within normal limits. HBsAg (-), anti-HCV (-), anti-HIV (-), thyroid function tests, anti-TPO antibody, and anti-TG antibody were normal. Other selected laboratory tests showed serum folic acid of 4.82 ng/mL (normal > 3.00 ng/mL), vitamin B12 of 226 pg/mL (normal: 160-980 pg/mL), ferritin of 3.3 ng/mL (normal: 5-148 ng/mL), serum iron of 6 g/dL (normal: 40-170 g/dL), and serum iron binding capacity of 470 g/dL (normal: 250-425 g/dL).

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a mild edematous appearance in intestinal walls with no other abnormalities. Colonoscopic examination of the terminal ileum revealed a normal mucosa and lumen. The ileocecal valve appeared to be normal. However, mucosa of the entire colon was diffusely hyperemic and edematous with disappearance of the submucosal vascular network, and scattered shallow ulcerations. Histopathological examination of colonic specimen showed chronic mucosal inflammation with cryptic abscesses and distortion, suggestive of ulcerative colitis. Treatment with mesalazine (5-ASA) at a dose of 2 g/d was commenced and the patient was asked to visit one month later.

One month later, her bloody diarrhea and skin lesions disappeared and she passed formed stools once a day. However, liver function tests remained elevated (67 U/L AST, 92 U/L ALT, 165 U/L ALP, and 224 U/L GGT). Thus, quantitative serum immunoglobulin tests were as follows: ANA (-), anti-ds DNA (-), AMA (-), ASMA (-), anti LKM-1 (-), SLA/LP M2 (-), p-ANCA (+), 1.33 g/L C3 (normal: 0.9-1.8 g/L), 0.15 g/L C4 (normal: 0.1-0.4 g/L), 19.10 g/L IgG (normal: 7-16 g/L), 1.56 g/L IgM (normal: 0.4-2.3 g/L), and 3.01 g/L IgA (normal: 0.7-4 g/L).

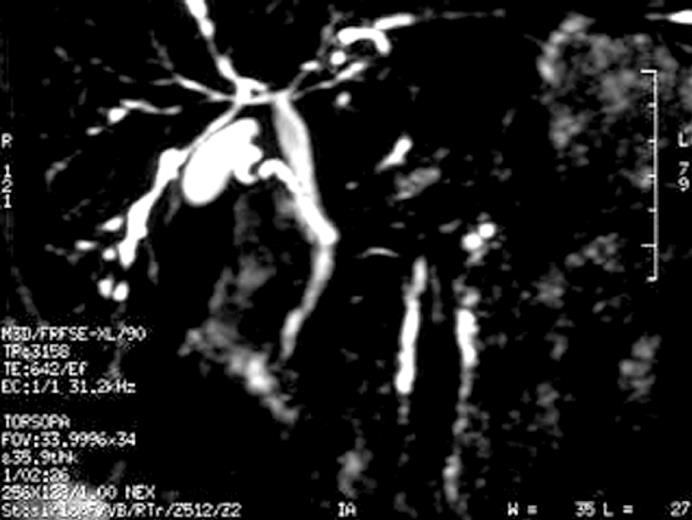

Since serum ALP and GGT values were high and p-ANCA was positive, a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography (MRCP) was performed with the suspicion of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). MRCP revealed ductal irregularities at distal branches of the right and left hepatic canals (Figure 2). Thus, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was started at a dose of 20 mg/kg, once a day, with a presumptive diagnosis of PSC. Following the treatment, her liver function tests returned to normal within two months. She was still well with oral 5-ASA and UDCA treatment at the time when we wrote this paper.

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography demonstrating ductal irregularities and beading appearence in the distal branches of the right and left hepatic canals.

DISCUSSION

Various skin findings can accompany inflammatory bowel disorders[2]. Skin manifestations occur in about 15% of patients with inflammatory bowel disorders[4]. Most frequently accompanying skin manifestations are pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum, while necrotizing vasculitis, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa and granulomatous perivasculitis are less frequently seen[5–8]. Although the etiopathogenesis of extra-intestinal manifestations is not clear, a partial defect of immunity common to the skin and intestines has been suggested[5].

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is a disorder characterized by neutrophilic infiltration and nuclear debris in postcapillary venules[19]. It is believed to be an immune-complex disorder triggered by various drugs, infections, malignancies, and systemic and autoimmune disorders[10–13]. Although it usually involves the skin, systemic manifestations such as fever, arthralgia, myalgia or asthenia may also develop[2]. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is less frequently seen in patients with ulcerative colitis as compared to other skin manifestations[14–18]. Clinically, it is generally synchronous with ulcerative colitis. Three previous ulcerative colitis cases who presented leukocytoclastic vasculitis before onset of the intestinal disease have been reported[315]. As reported by Newton et al[15], vasculitic symptoms appear 1 to 6 mo before the onset of intestinal symptoms. Iannone et al[3] reported another case whose intestinal disease occurred 2 years after appearance of vasculitic skin lesions. In our case, leukocytoclastic vasculitis developed 8 mo before the appearance of intestinal symptoms.

One possible explanation of the association between these two disorders can be that the pathogenesis of both is based on immune mechanisms and deposition of immune complexes in the vascular wall and intestinal mucosa for leukocytoclastic vasculitis and ulcerative colitis, respectively[19]. Another possible explanation might be that IBD is a systemic disorder involving different tissues (skin, joints, intestine) at different episodes[3].

Skin lesions of leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be treated with corticosteroids, dapsone, colchicine, or immunosuppre-sive agents[1]. The treatment can be directed to the underlying cause (i.e., drugs, infections, malignancies, autoimmune diseases), if it is present. As previously mentioned, cases of leukocytoclastic vasculitis accompanying ulcerative colitis can be effectively treated with colchicine and sulfasalazine. In our case, both intestinal symptoms and skin lesions were successfully treated with 5-ASA.

The other diagnosis of our patient was PSC. It was reported that the prevalence of PSC in patients with uncera-tive colitis is 5.5%[20]. ANCA positivity in patients with PSC is 56%-88%. Patients with PSC can be asymptomatic (25%-45%) at the time of diagnosis[21]. In our case, it is possible that PSC developed synchronously with leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Not any case in the literature presented PSC along with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

In conclusion, IBD should be kept in mind as a cause of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, although it is a rare occasion. A careful follow-up of such cases may improve both vasculitis and IBD.