Published online Apr 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2115

Revised: February 2, 2008

Published online: April 7, 2008

Castleman’s disease (CD) of the pancreas/peripancreas is extremely rare. The recently introduced, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-guided trucut biopsy (TCB) is a useful diagnostic modality for obtaining tissue samples from peripancreatic lesions. However, its role in diagnosing CD remains unknown. We report a case of localized, peripancreatic, hyaline-vascular CD biopsied using EUS. The pathology results were initially interpreted as an extranodal, marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma. However, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) study for the IgH gene rearrangement revealed a polyclonal pattern. We also reviewed the relevant literature. To our knowledge, this is the first illustrated report on EUS-TCB findings of CD with its pathology results of EUS-TCB mimicked a B-cell lymphoma.

- Citation: Rhee KH, Lee SS, Huh JR. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided trucut biopsy for the preoperative diagnosis of peripancreatic castleman’s disease: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(13): 2115-2117

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i13/2115.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.2115

Castleman’s disease (CD) of the pancreas/peripancreas is a very uncommon disease. The differential diagnosis of peripancreatic masses includes pancreatic cancer, tuberculous lymphadenopathy, lymphoma, neurogenic tumors such as paraganglioma, and CD. The initial challenge in CD is to establish its correct diagnosis. Radiology-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) of deep-seated masses is a standard means of obtaining a tissue diagnosis, but fails to make a definitive distinction from lymphoma[1]. Recently, the efficacy of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-guided TCB in diagnosing intra-abdominal/retroperitoneal benign lymph node enlargement or lymphoid malignancies has been reported. Herein, we present the EUS morphologic findings, microscopic examinations, and the advantage of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for IgH gene rearrangement in a case of peripancreatic CD which was initially sampled by EUS-TCB.

A previously healthy, 50-year-old woman was referred to our institution for further evaluation of a pancreatic mass which was incidentally detected on an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan performed at another hospital.

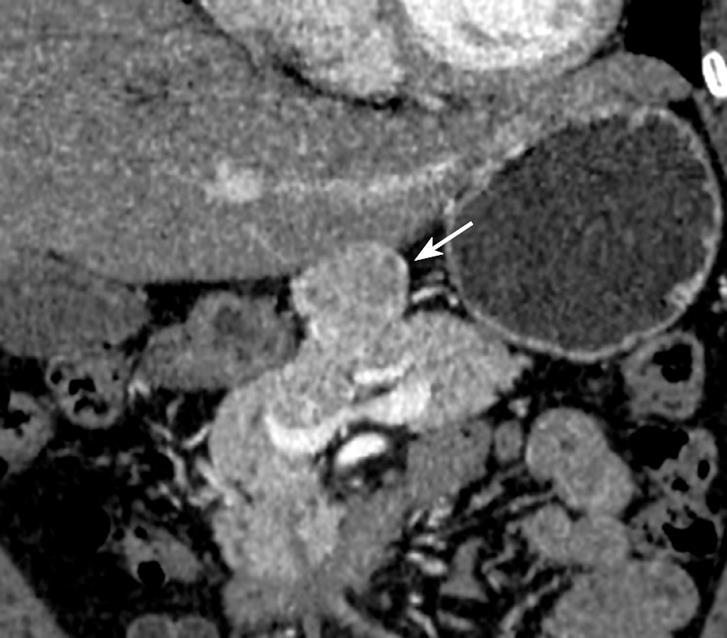

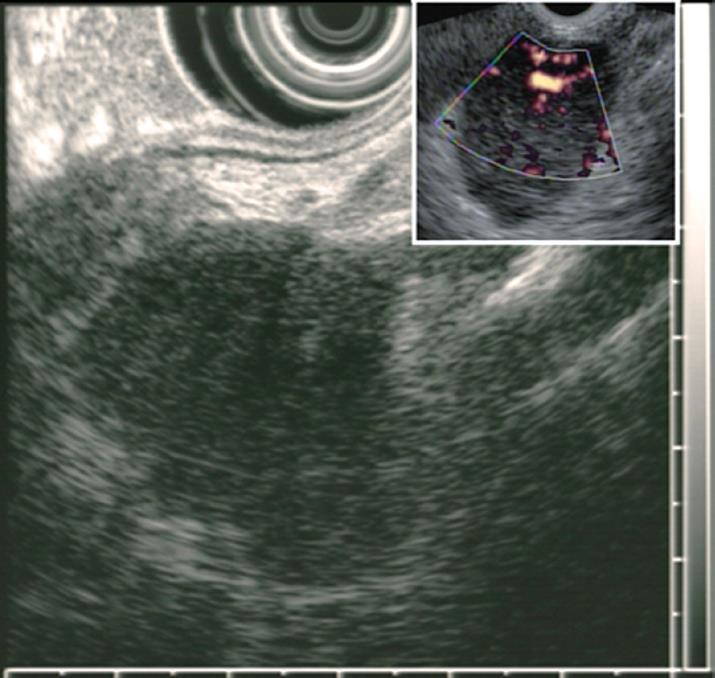

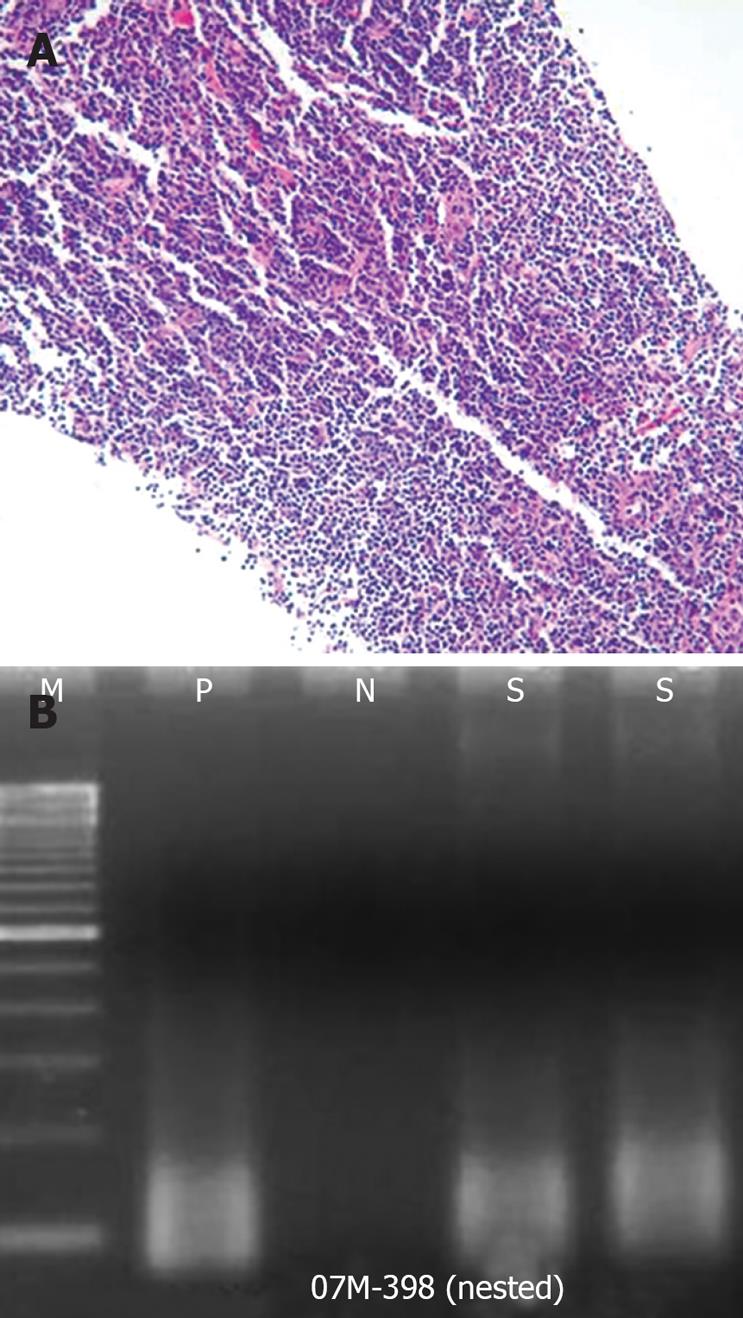

Dynamic CT scans of her pancreas disclosed an arterial, enhancing mass measuring 3.9 cm in the upper portion of the pancreas body (Figure 1). EUS (GF-UM2000; Olympus, Japan) demonstrated a homogenous, elongated, and well-delineated hypoechoic mass between the left lobe of liver and the body of the pancreas. The vascularity of the mass was high on Doppler US (Figure 2). A core biopsy specimen of the lesion was obtained using a 19-gauge, trucut needle (EUSN-19-QC, Cook) under the guidance of a linear-array echoendoscope (GF-UCT2000; Olympus, Japan). After the procedure, the patient had no immediate complications, such as bleeding, perforation or peritonitis. The size of the core biopsy specimen was about 1.1 cm in length, but it was fragmented into five pieces while putting into a tissue container. Microscopic examination showed expanded follicles replaced by dense infiltration of small, mature lymphocytes devoid of follicular center cells which caused an initial suspicion of low-grade, extranodal, marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma. However, according to PCR study for IgH gene rearrangement, the mass was seen to have a polyclonal pattern (Figure 3A and B).

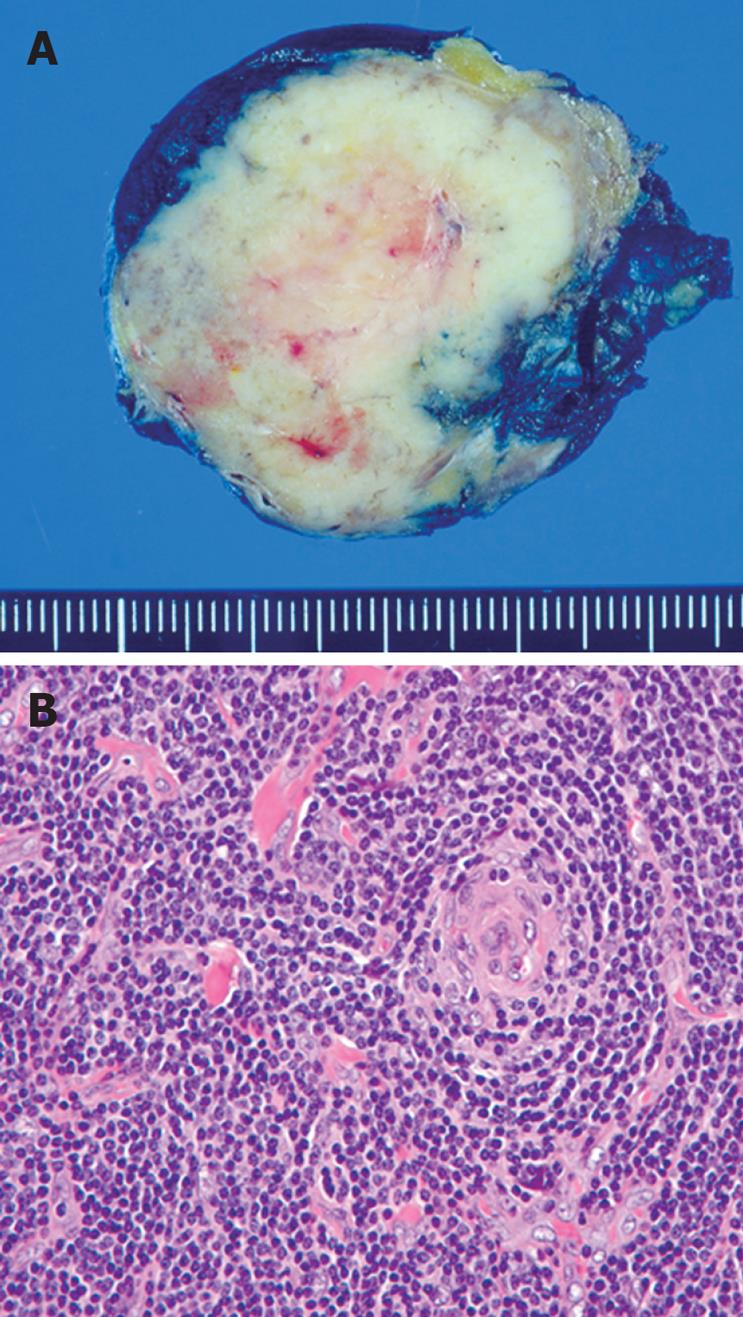

The patient underwent laparoscopic mass excision with curative intent as well as pathologic confirmation. The resected lesion was found to be a well-demarcated, lobulated, rubbery, firm mass (Figure 4A). Microscopically, the lesion was a markedly enlarged lymph node composed of numerous, prominent, lymphoid follicles with atrophic germinal centers devoid of follicle center cells (Figure 4B).

The final diagnosis was CD (angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia) of a hyaline-vascular (HV) variant. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and remained disease-free at the time when this report was prepared.

CD has been identified in a series of patients with solitary, hyperplastic, mediastinal lymph nodes with small germinal centers resembling Hassall’s corpuscles of the thymus[2]. CD can be divided into hyaline vascular type, plasma cell type, and mixed type or into unicentric or localized type and multicentric or generalized type[34]. The HV type accounts for 90% of all localized disease[5] and is often asymptomatic or, as in our patient, has symptoms caused by the mass effect of the lesion.

The clinical challenge in CD is to establish its correct diagnosis. Many imaging modalities, including CT, magnetic resonance (MR), angiography and FDG-PET, have been used to diagnose CD[6–9]. Nevertheless, it is the mainstay to obtain and analyze tissue samples for its final diagnosis.

EUS-, US- or CT- guided FNA of deep-seated masses are the standard means of obtaining tissue diagnosis, but cytomorphologic, flow cytometric, and immunohistochemical studies have failed to make a definitive distinction from certain kinds of lymphoma[1]. The reason is that FNA specimen is largely restricted in morphologic and immunohistochemical study for the shortage of sample size. On the other hand, EUS-TCB has a higher diagnostic yield and accuracy because it may obtain more adequate core specimens than FNA. It was reported that EUS-TCB has been used in diagnosing gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), leiomyoma, and lymphoma[1011].

Although the initial microscopic morphology of our case was similar to that of B-cell lymphoma, lymphoma was mostly excluded and CD was strongly suspicious prior to surgery with the help of PCR for IgH gene rearrangement.

In conclusion, peripancreatic CD is rare but should be considered in the differential diagnosis of peripancreatic lesions. The discrimination of CD from lymphoma could be difficult, but we believe that EUS-TCB is more useful in preoperative diagnosis than FNA.

| 1. | Meyer L, Gibbons D, Ashfaq R, Vuitch F, Saboorian MH. Fine-needle aspiration findings in Castleman's disease. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21:57-60. |

| 2. | Castleman B, Iverson L, Menendez VP. Localized mediastinal lymphnode hyperplasia resembling thymoma. Cancer. 1956;9:822-830. |

| 3. | Keller AR, Hochholzer L, Castleman B. Hyaline-vascular and plasma-cell types of giant lymph node hyperplasia of the mediastinum and other locations. Cancer. 1972;29:670-683. |

| 4. | Magrini U, Lucioni M, Incardona P, Boveri E, Paulli M. Castleman’s disease: update. Pathologica. 2003;95:227-229. |

| 5. | Frizzera G. Castleman’s disease and related disorders. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:346-364. |

| 6. | Kim TJ, Han JK, Kim YH, Kim TK, Choi BI. Castleman disease of the abdomen: imaging spectrum and clinicopathologic correlations. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:207-214. |

| 7. | Meador TL, McLarney JK. CT features of Castleman disease of the abdomen and pelvis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:115-118. |

| 8. | Chaulin B, Pontais C, Laurent F, De Mascarel A, Drouillard J. Pancreatic Castleman disease: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:160-161. |

| 9. | Soler R, Rodriguez E, Bello MJ, Alvarez M. Pancreatic Castleman's disease: MR findings. Eur Radiol. 2003;13 Suppl 4:L48-L50. |

| 10. | Eloubeidi MA, Mehra M, Bean SM. EUS-guided 19-gauge trucut needle biopsy for diagnosis of lymphoma missed by EUS-guided FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:937-939. |

| 11. | Saftoiu A, Vilmann P, Guldhammer Skov B, Georgescu CV. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided Trucut biopsy adds significant information to EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration in selected patients: a prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:117-125. |