INTRODUCTION

Nesidioblastosis is a term originally conceived by Laidlaw[1] who described the neoformation of the islets of Langerhans from the pancreatic ductal epithelium. This disease is a rare disorder of infants characterized by persistent hypoglycemia as a result of hypersecretion of insulin from β-cell hyperplasia of the pancreas[2]. First described in neonates, it is widely recognized as the primary cause of persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in infants[3]. However, in adults, hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia is caused mostly by an insulinoma, and onset nesidioblastosis in adults represents 0.5%-5% of cases of organic hyperinsulinemia[45]. Since the first reported series of onset nesidioblastosis in adults by Harness et al in 1981[6], limited cases have been reported to date[7–9].

We report herein a very rare case of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of an elderly man, which was negative in a localizing test for mass and positive in a selective arterial calcium infusion (SACI) test. He was found to have nesidioblastosis during a partial pancreatectomy.

CASE REPORT

A 71-year-old man was admitted to our hospital due to intermittent general weakness, abdominal pain, and mild dyspnea. The patient underwent a subtotal gastrectomy for a gastric adenocarcinoma 2 years ago. He had no history of diabetes mellitus or hypoglycemia. The patient had discomfort of the abdomen accompanying general weakness several months ago. After 5 d of admission, the patient showed abrupt symptoms of cold sweating, chilling, and hypotension 30 min after eating. These symptoms were relieved after intravascular administration of 50% glucose. Thereafter, the patient frequently showed similar symptoms accounting for hypoglycemia regardless of food consumption.

Laboratory findings determined when the symptoms were present revealed a low fasting blood glucose level (25-48 mg/dL), and a high insulin level (38-47 &mgr;IU/mL). A 72-h fasting glucose study failed because of the occurrence of hypoglycemic shock 4 h after commencement of the test.

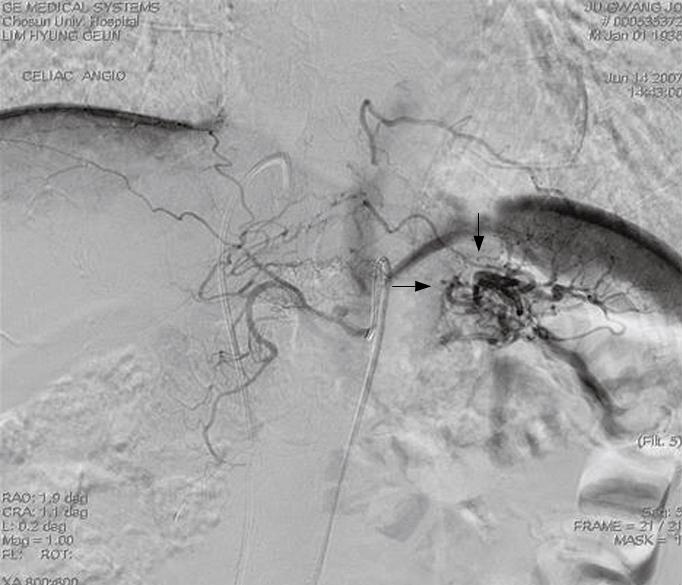

Endocrine examinations to exclude other causes of hypoglycemia, such as hypopituitarism and adrenal insufficiency, were within the normal range. The above-described symptoms and the results of serological tests were consistent with those of insulin-producing lesions including an insulinoma. However, imaging studies including computed tomography and a sonogram of the abdomen failed to detect a mass except for a highly vascularized area in pancreatic tail (Figure 1). To exclude any possible occult insulinoma, selective intra-arterial calcium stimulation with hepatic venous sampling (ASVS) was performed. After calcium gluconate (0.05 mg/kg body weight) was injected into the splenic, hepatic, gastroduodenal, and superior mesenteric arteries, blood samples were collected from the right hepatic vein every 30 s for 120 s. A selective arterial calcium injection test (SACI) to the left splenic artery increased the insulin level of about 4-fold over the pre-stimulated level. In contrast to the left splenic artery, no significant increment was induced by the SACI to the hepatic, gastroduodenal, and superior mesenteric arteries, suggesting the presence of an insulinoma in the tail of pancreas. Under the assumptive diagnosis of an insulinoma of pancreatic tail based on the ASVS test, a distal pancreatectomy was performed. Neither intraoperative exploration nor a frozen biopsy specimen detected any mass-forming lesion. Grossly, the resected pancreas appeared normal, and there was no mass lesion in serial section specimens.

Figure 1 Celiac angiography showing a hypervascular mass-like lesion in the pancreatic tail area (arrows).

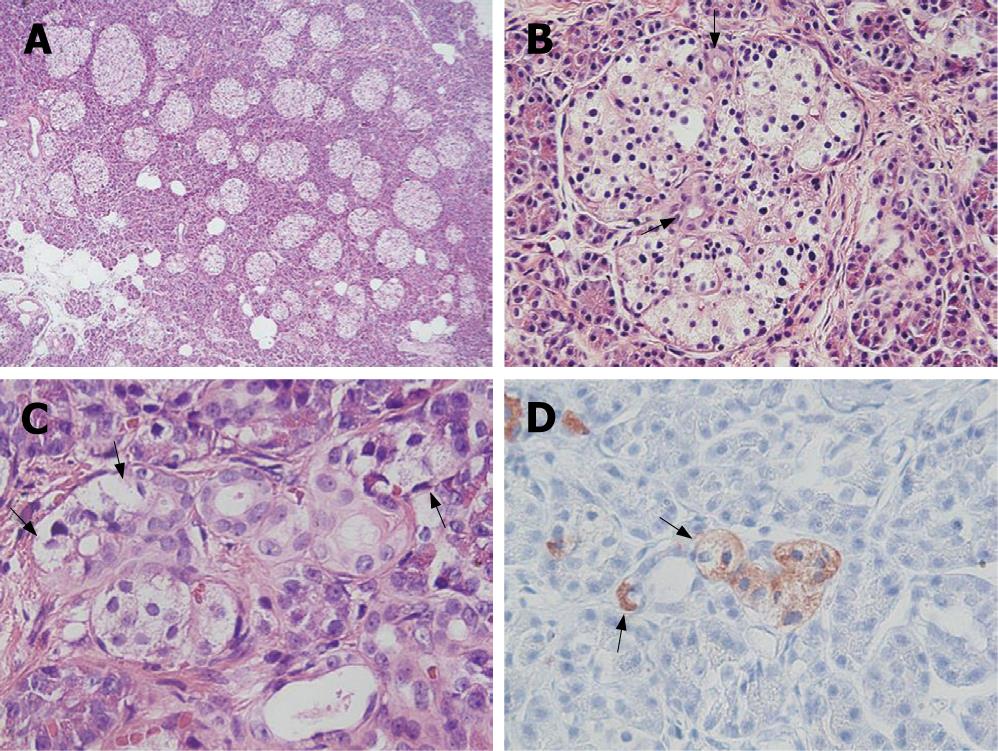

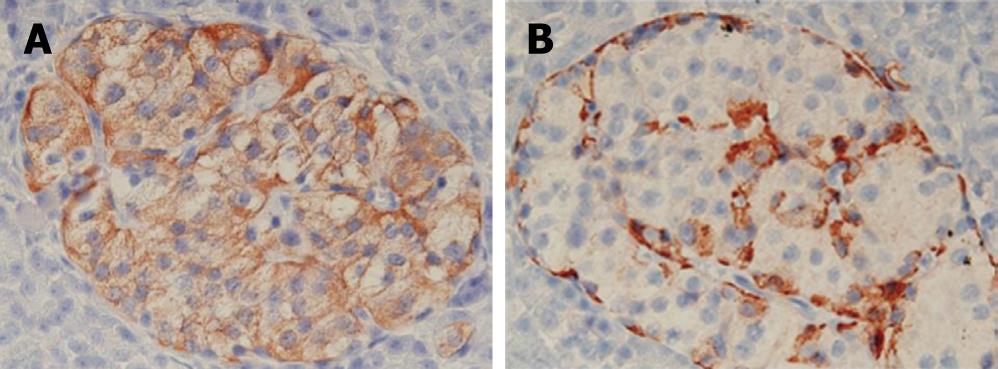

In a histopathological study, a number of dysplastic islets were randomly scattered throughout the pancreatic parenchyma, and their contour and size were markedly variable as compared to the normal pancreatic parenchyma. Ductuloinsular complexes and insulin-positive cells budding off the duct epithelium were also observed (Figure 2). Focally, the distribution of islets was densely crowded. In the majority of islets, multiple β-cells with enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant clear cytoplasm were identified (Figures 2 and 3). Immunohistochemically, the number of insulin-secreting β-cells was increased, and the number of glucagon-secreting α-cells was decreased (Figure 3). These clinical, radiological, histopathological, and immunohistochemical findings were consistent with those of nesidioblastosis.

Figure 2 Irregularly sized-dysplastic islets scattering randomly throughout the pancreas (A), islets in intimate association with ducts forming a so-called ductulo-insular complex (arrows indicate ductules within the islet) (B), islet cells (arrows) budding off the duct epithelium (C), insulin-positive islet cells (arrows) budding off the duct epithelium (immunohistochemical stain for insulin) (D).

Figure 3 An immunohistochemical study showing increased insulin producing β-cells (A), glucagon producing α-cells (B).

In the post-operative course, the glucose and insulin levels in the patient were well controlled and uneventful for two weeks after surgery. However, beyond that time, the patient repeatedly showed hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia with no response to medication.

DISCUSSION

Nesidioblastosis is the name given to the presence of islets in intimate association with ducts, formation of so-called ductulo-insular complexes[1011]. In adults, an insulinoma accounts for most cases of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia[412]. Nesidioblastosis has mainly been described in neonates[3]. Since Harness et al[6] first described nesidioblastosis in adults, it has only been reported in association with other diseases, such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, multiple endocrine adenomatosis, β-cell adenomatosis, Lindau’s disease, cystic fibrosis, insulinomas, pancreatic transplantation, orbital lymphoma with hypopituitarism and adrenal insufficiency, familial adenomatous polyposis, hypergastrinemia, and pancreatic polypeptidemia[7].

The morphological criteria[1314] for establishing its diagnosis are the presence of differently-sized islets often with somewhat irregular outline, and irregularly sized and poorly defined endocrine cell clusters scattered in the acinar parenchyma and often intimately connected with small or large ducts (ductuloinsular complexes). Another feature is a distinct islet cell hypertrophy with nuclear enlargement, often resulting in the presence of giant and bizarre nuclei. As seen by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy, these cells are found to be insulin-producing cells. The histopathological findings in the present case were compatible with these criteria. Nesidioblastosis is classified into focal and diffuse types characterized by different clinical outcomes[15]. Focal nesidioblastosis exhibits nodular hyperplasia of islet-like cell clusters, including ductuloinsular complexes and hypertrophied insulin cells with giant nuclei. In contrast, diffuse nesidioblastosis involves the entire pancreas with irregularly sized islets[10].

Sporadic hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia is the main clinical feature of nesidioblastosis. The present patient had frequently hypoglycemic episodes mostly in the afternoon and night, independent of food consumption. It should be noted that a gastrectomy may evoke hypoglycemia, which is sometimes severe enough to cause loss of consciousness as a neurologlycopenic symptom[16]. However, postprandial hypoglycemia following a gastrectomy usually occurs 1.5 to 3 h after food digestion[17]. The present case did not show characteristic postprandial hypoglycemia and the hypoglycemic symptoms improved during the two weeks after surgery, suggesting that this kind of hypoglycemia results from nesidioblastosis rather than from gastrectomy. Additionally, it is assumed that past history of a gastrectomy may have partly aggravated the hypoglycemia in addition to the effect of nesidioblastosis.

When clinical examinations including ASVS suggest nesidioblastosis, a partial pancreatectomy is usually performed. Even if a frozen biopsy confirms the diagnosis of nesidioblastosis, the extent of pancreatic resection remains questionable. A distal pancreatectomy which can control the symptoms of the majority of patients, is well tolerated, and does not induce endocrine or exocrine insufficiency. Recovery after a partial pancreatectomy can remove enough abnormal proliferative tissue to achieve normoglycemia[418]. However, some investigators recommend an initial near-total pancreatectomy. Such extensive resections lead to an increased risk of post-surgical diabetes and pancreatic insufficiency. It seems that the best recommendation is a 70%-80% pancreatectomy, administration of diazoxide when hypoglycemia persists post-operatively, and a more extensive resection when previous measures fail[19–21].

In summary, we report here a case of nesidioblastosis of a patient having a history of a subtotal gastrectomy based on a diagnosis of a gastric adenocarcinoma. ASVS can detect a hyperinsulinemic lesion of the distal pancreas. However, sporadic hypoglycemia may occur after surgery, and is refractory to medication. Further study is needed to improve its treatment.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Yin DH