CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old woman presented with acute-onset, sharp abdominal pain. The pain had developed 4 d prior to referral to our department from a local hospital for further evaluation of abdominal pain. On admission, her vital signs were normal. She denied other gastrointestinal symptoms and signs such as nausea, vomiting, abnormal bowel habits, melena or hematochezia, except for sharp abdominal pain. She also denied weight loss, fever, or other systemic symptoms. She had no medical or family history. Physical examination showed mild abdominal tenderness in the hypogastrium, but no palpable abnormal abdominal mass. Her laboratory findings, including tumor markers, were unremarkable, except for a normocytic, normochromic anemia: hemoglobin, 9.86 g/dL; hematocrit, 28.6%; mean corpuscular volume, 100.4 fL; and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 54 mm/h. The chest and abdominal X-ray films revealed no abnormal findings. Abdominal CT demonstrated a mass of approximately 8 cm in the gastrocolic ligament or gastric wall (Figure 1), and abdominal MRI showed a heterogeneous mass of approximately 8 cm in the gastrocolic ligament or gastric wall (Figure 2).

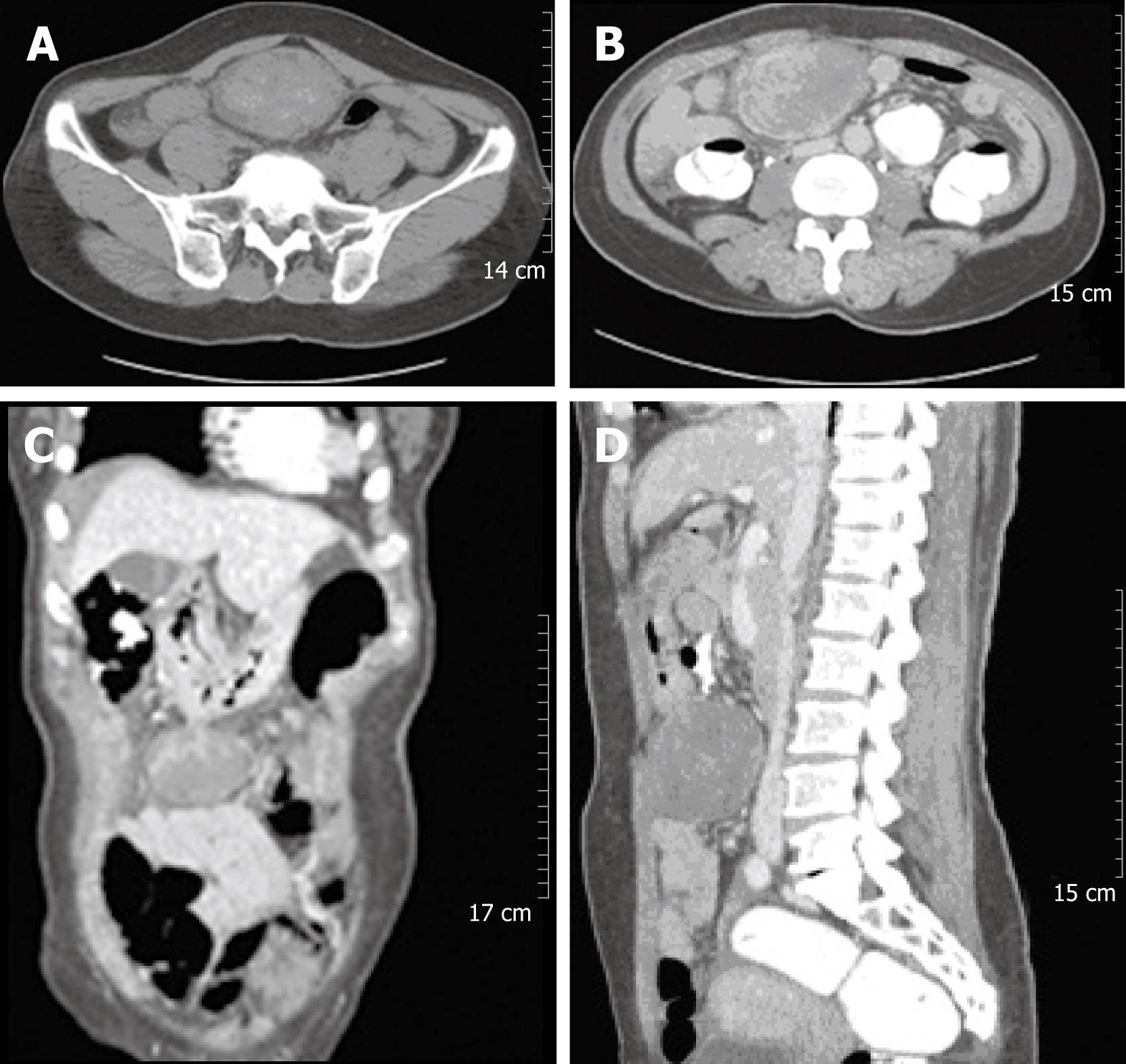

Figure 1 Abdominal CT revealed a large solid mass at the gastrocolic ligament or the gastric wall, which showed heterogeneous density on an non-enhanced image (A).

The 8 cm mass showed internally enhanced vessels on the arterial phase of CT and delayed peripheral enhancement of the mass on the venous phase (B-D).

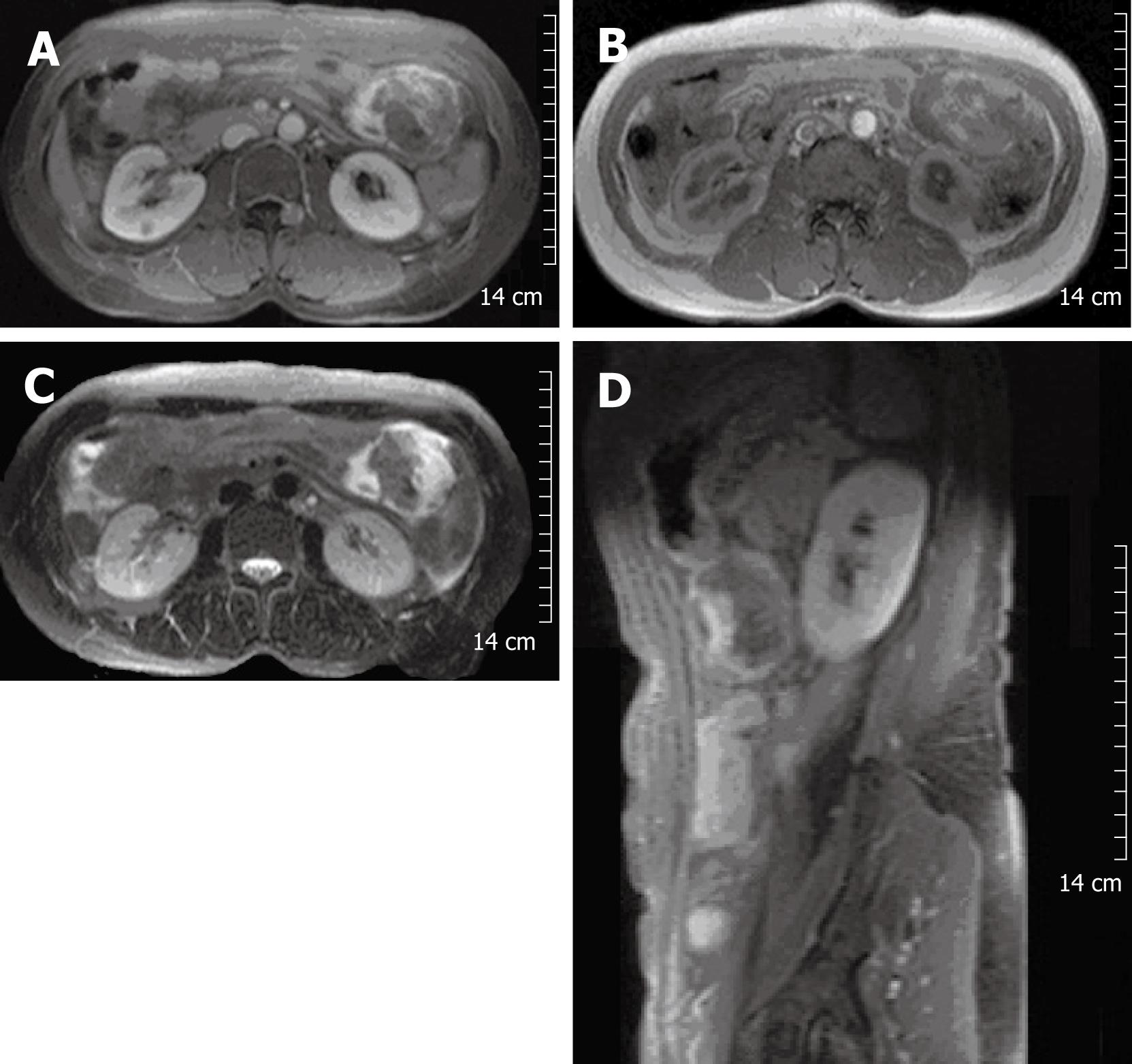

Figure 2 Contrast-enhanced MRI of the abdomen showed a mass of approximately 8 cm, seen at the left upper quadrant of the abdomen.

The margin of the mass was lobulating, and it was attached to the greater curvature of the stomach. It contained a peripheral enhanced solid portion and a central non-enhancing portion (A). Signal intensity of the central non-enhancing portion was low on T1WI (B) and T2WI (C and D), which suggested internal hemorrhage within the tumor.

Endoscopic examination, including colonoscopy, showed no luminal or mucosal lesion and no remarkable findings, except chronic atrophic gastritis with Helicobacter infection. Routine gynecological evaluation was unremarkable. After the work up for the intra-abdominal mass, her abdominal pain completely subsided at the time of operation.

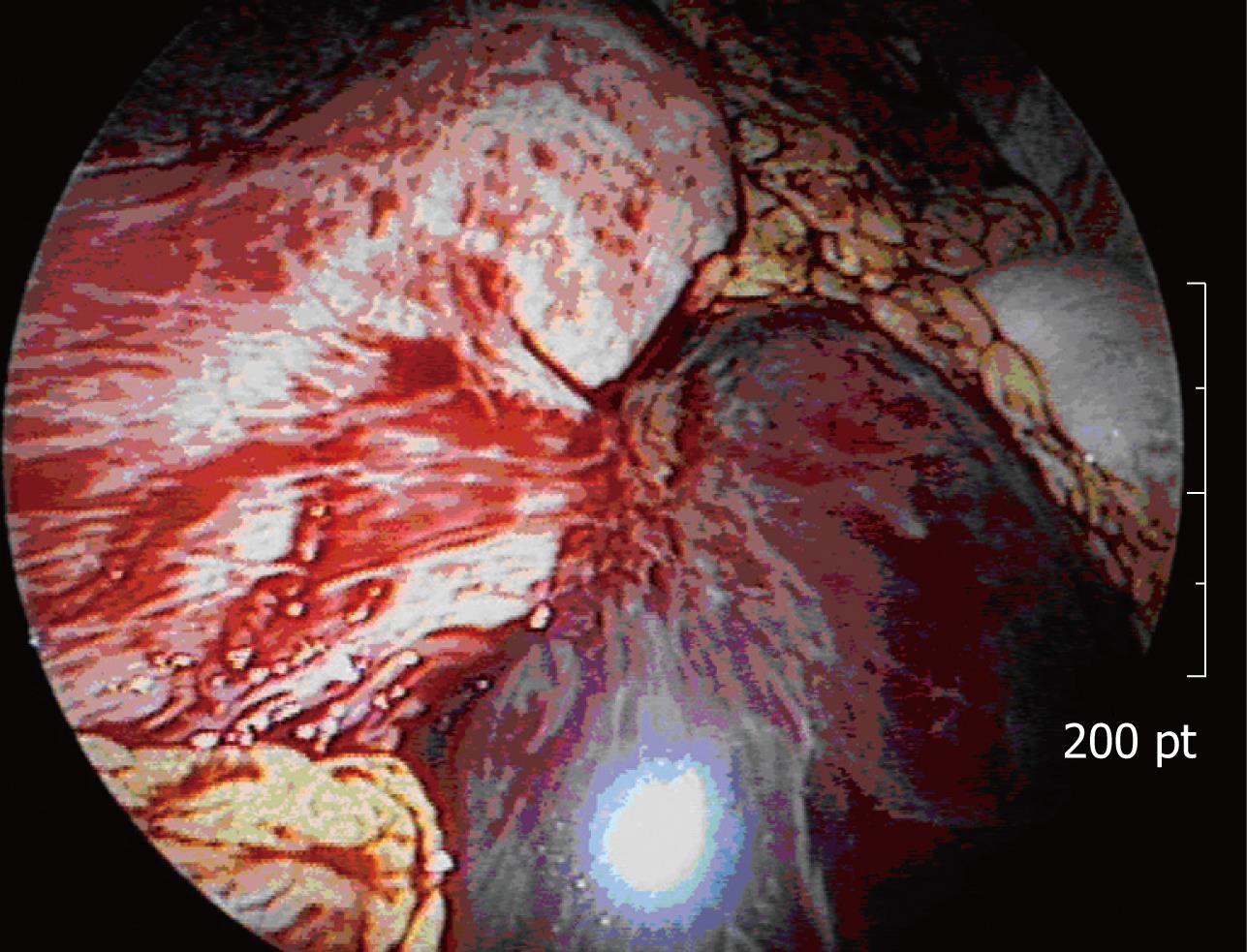

The patient underwent laparoscopic exploration. Unexpected hemoperitoneum of approximately 1.5 L of non-clotting blood was found. An exophytic gastric mass from the anterior wall of the gastric body along the greater curvature appeared, similar in appearance to the spleen or a hematoma, approximately 10 cm in size (Figure 3). Laparoscopic diagnosis was massive intra-abdominal hemorrhage from the gastric tumor or ectopic spleen. Since further evaluation of the precise cause of hemoperitoneum was needed, and because it would have been difficult to remove the large friable tumor from the abdominal cavity, even after a safe laparoscopic resection we decided to convert to open surgery.

Figure 3 Laparoscopic view of the exophytic gastric mass with a large amount of intra-abdominal non-clotting hemorrhage.

After evacuation of blood, the abdominal cavity was thoroughly explored for any other source of bleeding, but none was found; the permeated or ruptured exophytic gastric mass was the cause of hemoperitoneum, because preoperative imaging studies, including gynecologic evaluation during admission, showed no evidence of intra-abdominal fluid, and also no other identified focus of bleeding upon surgical exploration. The tumor showed a dark reddish pedunculated mass with a stalk that originated from the gastric wall, but there was no blood vessel directly into the tumor. During dissection, we could not find any tear or rupture on the exophytic tumor. Gastric wedge resection, including the tumor and greater omentum, was conducted.

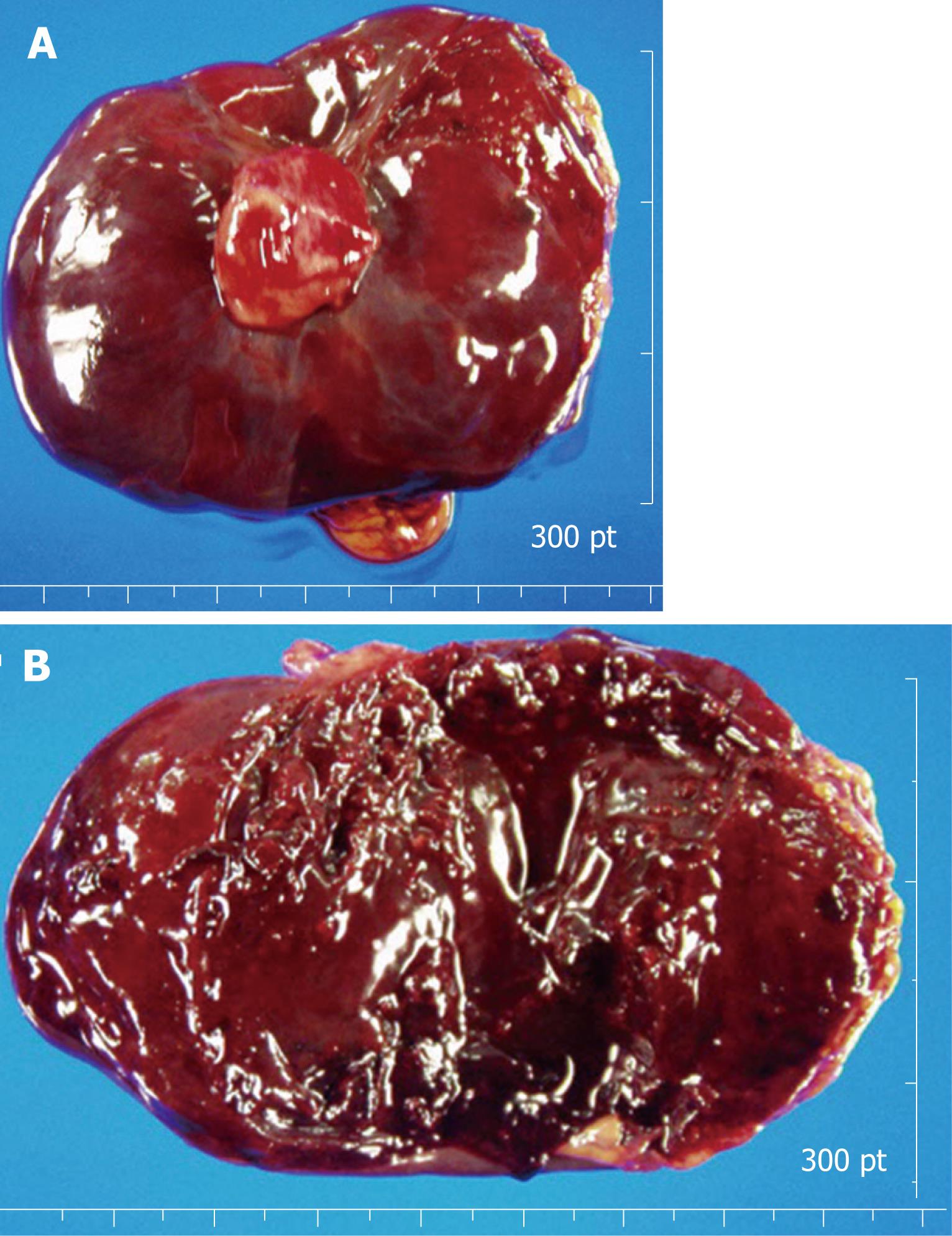

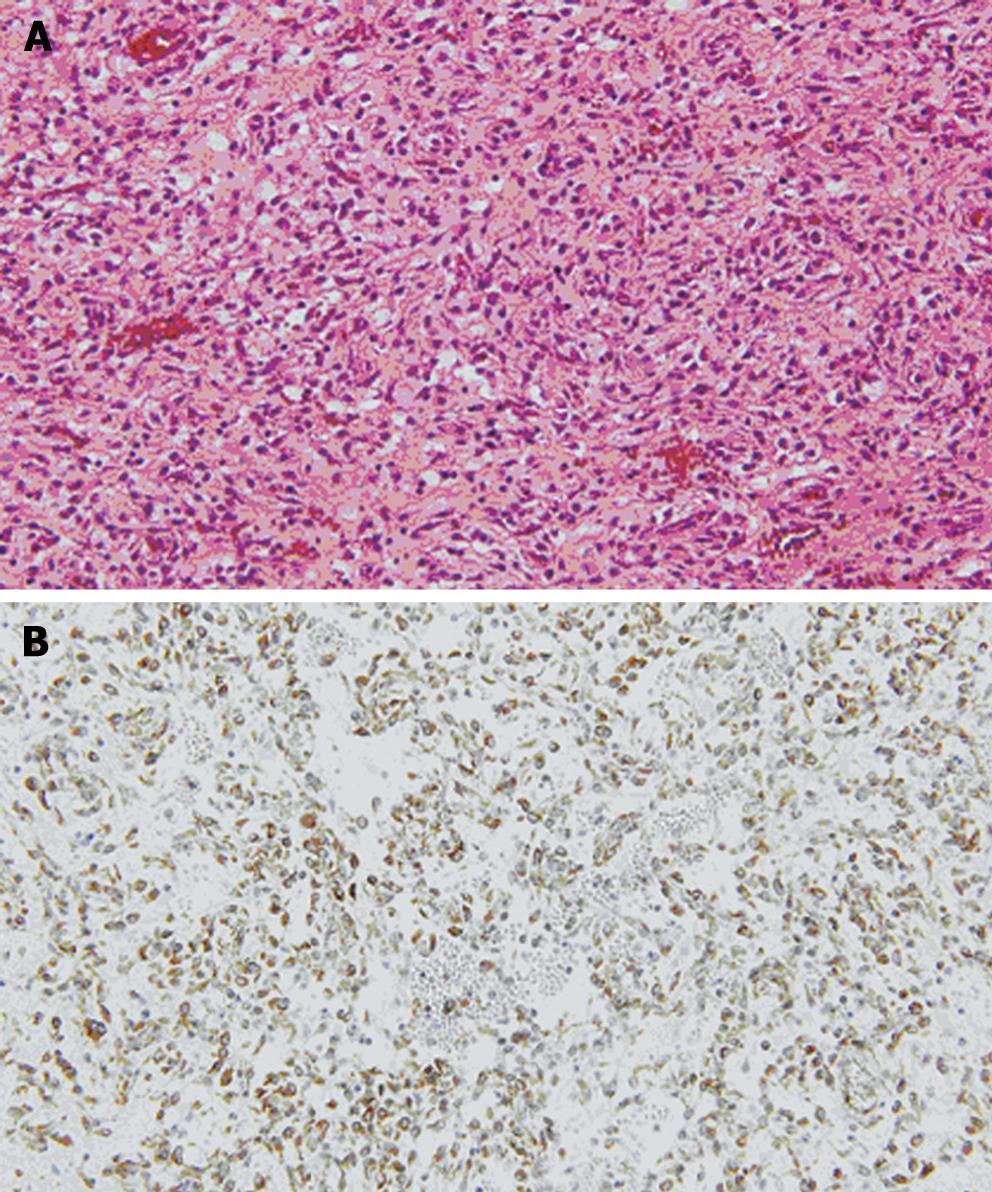

Grossly, the external surface of a well-encapsulated lump of soft solid tumor was smooth and glistening, but there was no gastric mucosal lesion (Figure 4A). The tumor measured 8.5 cm × 7.1 cm × 3.6 cm and weighed 88.1 g, and its stalk measured 2.0 cm × 1.2 cm × 1.9 cm. On serial sectioning, the cut surface was characterized by several amorphous fragments of parenchymal tissue, which were separated by the cystic spaces (Figure 4B). Histologically, the tumor was composed of round and spindle-shaped myofibroblastic cells, diffusely scattered inflammatory cells, and many vascular structures (Figure 5A). The mitotic count was 1/10 high power fields (HPF). The tumor cells showed positive immunoreactivity for vimentin (Figure 5B), while being negative for c-kit, CD34, desmin, smooth muscle actin (SMA), S-100, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), β-catenin, and CD31. Ki-67 labeling index was approximately 10%. Lymph nodes found along the gastroepiploic vessels in the omentum were all negative for tumor. The final pathologic diagnosis was consistent with IMT that originated from the gastric wall.

Figure 4 The external surface of a well-encapsulated lump of soft solid tumor, weighing 88.

1 g, was smooth and glistening, but showed no gastric mucosal lesion (A). Cross-sectional surface of the tumor was characterized by several amorphous fragments of parenchymal tissue, which were separated by the cystic spaces (B).

Figure 5 A: The tumor was composed of round and spindle-shaped myofibroblastic cells.

Diffusely scattered inflammatory cells and many vascular structures are seen (HE, × 400); B: The tumor cells showed positive immuno-reactivity for vimentin (× 400).

The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and has been followed up, including positron emission tomography, for any recurrence.

DISCUSSION

IMT is a rare, distinctive disease. Various terms such as inflammatory pseudotumor, plasma cell granuloma, inflammatory myofibroblastoma, and inflammatory myofibrohistioblastic proliferation have previously been used to describe the disease[3], which indicates that the exact nature of IMT is not yet fully understood. It has been debated whether IMT is a tumor or inflammation, and also whether it is benign or malignant[1]. However, recent studies on cytogenetic abnormalities, such as rearrangements of the ALK gene on chromosome 2p23[45], clonal chromosome abnormalities[6–8], and DNA aneuploidy[9], and the role of oncogenic viruses[1011] in the pathogenesis of IMT suggest that it is a true neoplasm. According to the current classification of the World Health Organization[12], IMT is a neoplasm with a tendency for local recurrence and a very low rate of metastasis, and is histopathologically composed of myofibroblastic spindle cells, with inflammatory cell infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes and eosinophils.

It was once accepted that IMT is primarily a disease of children and young adults and commonly occurs in the lungs[1314]. However, a recent study by Coffin et al has shown that IMT may span the entire age range and can occur in any site of the body[1]. Nevertheless, gastric IMT in adults is still a very rare disease. Only four case reports of gastric IMT in adults exist in the English literature: Kim et al have reported a gastric IMT with peritoneal dissemination in a young adult[15]; Al-Taie et al have reported a rapidly growing inflammatory tumor after triple therapy for benign gastric ulcer[16]; Leon et al have experienced an IMT of the gastric remnant in a 50-year-old woman with a prior gastrectomy[3]; and Kojimahara et al have described a large, poorly demarcated, elevated IMT with infiltrative proliferation of spindle cells over the full thickness of the gastric wall in a 19-year-old woman[17].

This is believed to be the first case report of an exophytic gastric IMT that spontaneously bled into the peritoneal cavity and developed into hemoperitoneum. The present case can be compared with other intra-abdominal IMTs that present with an abdominal mass and related compressive symptoms, such as abdominal pain and vomiting[315–18].

Most IMTs require surgery to obtain definite diagnosis and cure. Complete resection is the preferred option, because incomplete excision has been shown to be a risk factor for recurrence[13]. As evident in this case, microrupture of the solid tumor might be another risk factor for early recurrence.

The main difficulty in the management of IMT lies in the unpredictable postoperative course. There are no definitive clinical, histopathological, or genetic features to predict recurrence or metastasis. Recently, reactivity of ALK has been reported to be a favorable prognostic indicator[1]. Differentiation between aggressive and non-aggressive forms of IMT remains to be further clarified.

We reported a case of gastric IMT that spontaneously bled into the peritoneal cavity during admission. The patient is currently undergoing careful follow-up, because it is not clear whether gastric IMT is benign.