Published online Mar 7, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i9.1427

Revised: January 18, 2007

Accepted: February 9, 2007

Published online: March 7, 2007

AIM: To investigate the long-term results of liver transplantation (LT) for non-acetaminophen fulminant hepatic failure (FHF).

METHODS: Over a 20-year period, 29 FHF patients underwent cadaveric whole LT. Most frequent causes of FHF were hepatitis B virus and drug-related (not acetaminophen) liver failure. All surviving patients were regularly controlled at the out-patient clinic and none was lost to follow-up. Mean follow-up was 101 mo.

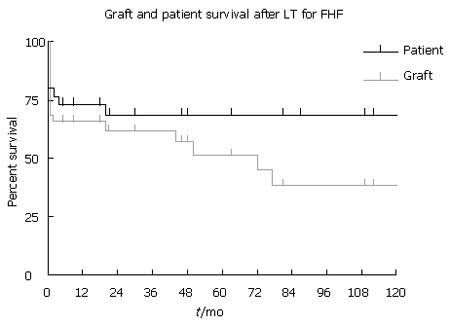

RESULTS: One month, one-, five- and ten-year patient survival was 79%, 72%, 68% and 68%, respectively. One month, one-, five- and ten-year graft survival was 69%, 65%, 51% and 38%, respectively. Six patients needed early (< 2 mo) retransplantation, four for primary non-function, one for early acute refractory rejection because of ABO blood group incompatibility, and one for a malignant tumor found in the donor. Two patients with hepatitis B FHF developed cerebral lesions peri-transplantion: One developed irreversible and extensive brain damage leading to death, and one suffered from deep deficits leading to continuous medical care in a specialized institution.

CONCLUSION: Long-term outcome of patients transplanted for non-acetaminophen FHF may be excellent. As the quality of life of these patients is also particularly good, LT for FHF is clearly justified, despite lower graft survival compared with LT for other liver diseases.

- Citation: Detry O, Roover AD, Coimbra C, Delwaide J, Hans MF, Delbouille MH, Monard J, Joris J, Damas P, Belaïche J, Meurisse M, Honoré P. Cadaveric liver transplantation for non-acetaminophen fulminant hepatic failure: A 20-year experience. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(9): 1427-1430

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i9/1427.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i9.1427

Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) is a rare but a dreadful disease affecting mostly young patients. FHF is mainly managed based on symptoms and the identification of the FHF causes requiring specific treatment and supportive care, as FHF patients have chances of recovery[1]. The main causes of death of FHF patients are intracranial hypertension leading to brain stem death, and sepsis with multiple organ failure (MOF)[2]. Many liver support systems have been tried, but the ideal and efficient artificial liver has still to be designed and its efficacy to be proven[3]. In the sickest cases, when established predicting factors of death are reached, liver transplantation (LT) has been established as the standard treatment for FHF patients[4]. However, the results of LT for FHF may be disappointing, especially compared with the results of LT for chronic liver diseases since FHF patients often suffer from risk factors for graft failure or high morbidity or/and mortality[5].

In the United States of America (USA) and in the United Kingdom (UK), FHF is very frequently caused by acetaminophen intoxication[6-9]. However this etiology is far less frequent in other Western countries. The aim of this study is to report the 20-year experience and the results of LT for non-acetaminophen FHF of the liver transplantation program of the University of Liège, Belgium, a transplantation center working within the Eurotransplant allocation system. As many variables changed during such a long period of time, the authors focused this report on the outcome of FHF patients who underwent LT.

The liver transplantation program of the University of Liège started in 1986[10]. From 1986 to December 2005, 345 cases of LT were performed, mostly in adult patients, including 7 adult-to-adult living-related LT[11]. Among this series, 58 patients were listed for Hyper Urgent (HU) LT, meaning patients with FHF, or patients requiring urgent retransplantation for primary non-function (PNF) or vascular thrombosis after LT. Thirty-two patients were registered for FHF. All these patients were suffering from FHF as defined by the occurrence of encephalopathy within 8 wk after jaundice development in patients without previous histories of liver disease[12]. All reached the established criteria for bad prognosis as established by the Clichy’ s group (non-acetaminophen FHF group) or the King’s College (acetaminophen FHF group)[13,14]. Three patients who suffered from acetaminophen FHF and who met the King’s College criteria for bad prognosis, recovered under medical therapy and intravenous N-acetylcysteine therapy. They were removed for subsequent analysis.

All patients were hospitalized in the intensive care unit and underwent standard medical therapy[1]. None but one patient received liver support with the Molecular Adsorbents Recirculating System (MARS). Patients in encephalopathy stage III were intubated for airway protection, if necessary. Continuous veno-venous hemofiltration was used for renal support. No patient underwent intracranial pressure monitoring.

All patients were registered for HU cadaveric LT in the Eurotransplant allocation system. Until 1992, transplantation of an ABO non-compatible liver graft was authorized for recipient life-saving purpose. As results of the non-compatible LT were not satisfactory in terms of graft survival, ABO compatible LT was required after 1992. All patients were transplanted with cadaveric whole liver. Orthotopic whole LT with veno-venous bypass was performed as the standard LT procedure from 1986 to 1994. After 1995 the standard surgical procedure for LT was the Belghiti’s technique, i.e. a piggy-back LT with temporary surgical porto-caval shunt, without use of veno-venous bypass and with large cavo-caval side-to-side anastomosis as venous reconstruction[15,16]. During this 20-year period, many other variables changed in the management of patients with FHF and of LT recipients. Immunosuppressive protocols in triple therapy regimens included cyclosporine/tacrolimus, Imuran/Cellcept and steroids. Steroids were progressively weaned, and most patients were under calcineurin inhibitor monotherapy at one-year follow-up. Patients transplanted for hepatitis B virus (HBV) FHF received life-long immunoprophylaxis with intravenous anti-HBs antibodies (10 000 UI every 3-4 mo, aiming at a minimum blood level > 100 mUI/mL).

All surviving patients were regularly controlled at the out-patient clinic and none was lost to follow-up. Mean follow-up was 101 mo (range: 5-204 mo). Statistical analysis was undertaken using patient and graft survival as endpoints. Survival was calculated using the method of Kaplan-Meier.

Twenty-nine patients (nine males, twenty females; mean age 39 years, range: 14-66 years) who developed non-acetaminophen FHF, were listed for cadaveric LT and underwent transplantation. The etiology of FHF is presented in Table 1. Most frequent causes of FHF in this group were hepatitis B virus (HBV) and drug-related. Three patients were in encephalopathy stage II, 10 in stage III and 16 in stage IV, at time of LT listing. Mean factor V level was 16% (range: 5%-31%). Mean waiting time between listing for HU LT and availability of a liver graft was 23 h (range: 4-49 h). Twenty patients were mechanically ventilated at time of listing and until LT. Nineteen developed acute renal failure and needed hemofiltration. Mean cadaveric donor age was 40 years (range: 14-57 years). Mean total graft ischemia was 417 min (range: 245-750 min). One month, one-, five- and ten-year survival was 79%, 72%, 68% and 68%, respectively (Figure 1). All patients who survived the first two years were alive at follow-up. Causes of early death (< 2 mo) were MOF, PNF (1 case) and peri-operative brain death (1 case). The only patient who died after 2 mo was not compliant to medical therapy after transplantation, suffered from chronic allograft rejection but was denied for re-transplantation (died at 18 mo of follow-up).

| Causes | No. |

| Viral infection | 12 (HBV: 11, HAV: 1) |

| Drug induced | 5 |

| Miscellaneous | 7 |

| Budd-Chiari | 1 |

| Wilson | 2 |

| Ischemic | 2 |

| Alcohol | 1 |

| Autoimmune | 1 |

| Undetermined | 5 |

Six patients needed early (< 2 mo) re-LT, 4 for PNF, 1 for early acute refractory rejection because of ABO blood group incompatibility, and 1 for a malignant tumor found in the donor[17]. Three patients needed late (> 2 mo) re-tranplantation due to chronic rejection or chronic graft dysfunction due to ABO blood group incompatibility in two cases and to non-compliance in one case. One patient needed a third transplantation because of chronic cholangitis on the second graft. One month, one-, five- and ten-year graft survival was 69%, 65%, 51% and 38%, respectively (Figure 1).

In the group of long-term survivors, two young females later enjoyed a total of three normal pregnancies. Among the patients transplanted for HBV FHF, one developed HBV graft reinfection treated first by lamivudine, and afterwards adefovir when the virus became resistant to lamivudine. This patient is well at follow-up, with graft fibrosis at biopsy. Two patients with HBV FHF, developed cerebral lesions during the peri-transplantation period: one developed irreversible and extensive brain damage leading to death, and one suffered from deep deficits leading to the continuous medical care in a specialized institution.

FHF is nowadays a well-admitted indication for urgent liver transplantation if the King’s College or Clichy’s criteria are met. According to the European Liver Transplant Registry (http://www.eltr.org), 9% of the LT performed in Europe are performed for FHF. In our experience at the University of Liège, FHF represents 8.5% of the indications of LT. If acetaminophen intoxication is one of the main indications in the USA and UK, this etiology is rare in other Western countries. In the authors’ experience, only three patients were listed for LT because of liver failure due to acetaminophen overdose in a 20-year period, and these three patients recovered on medical therapy including intravenous N-acetylcysteine, while listed for urgent LT. It is therefore important to assess the results of LT in patients with liver failure due to other causes, to confirm long-term survival despite a very unstable medical condition at the time of listing and at the time of transplantation. This is the case, as 68% of the patients transplanted for FHF were alive at the 10-year follow-up.

In our experience, HBV infection represents the main cause of FHF leading to LT (38%). In the 1990’s, systematic vaccination against HBV was initiated in Belgium. This policy reduced the frequency of HBV FHF in the native population, but recent immigrants still face HBV-related FHF. Drug-related FHF represents the second identified cause of FHF in this series (17%), and in five other cases we were not able to define the causative factor, as it was frequently reported in other series[18].

In our series the patients who underwent LT for FHF enjoyed excellent long-term survival, 68% of them were alive and well at 10-year follow-up. These results compare favorably to other series of the literature[4,13,18-21]. Moreover, as our experienced showed, if the patients survived the peri-operative period, they would have a good hope of survival with a low risk of late death. They also enjoy a very good quality of life with a low risk of liver disease recurrence or chronic rejection if they are compliant to the medical treatment. However, these good results in terms of graft survival are obtained at the price of a high rate of re-transplantation, as graft survival rate was 38% at 10 years.

The main cause of death in our series was MOF. This is certainly linked to medical status of these instable patients who often suffered from kidney and respiratory failure at the time of transplantation. This is also related to the high rate of PNF and the urgency for LT in this indication. This series also showed the efficiency of the Eurotransplant organization in providing rapidly a cadaveric liver graft for these urgent patients. In the early period of this experience, transplantation of an ABO uncompatible graft was allowed as a life-saving bridge to a later compatible graft. However, this policy was not prolonged because it consumes two grafts at a time of organ shortage. However, the change of policy did not have a significant impact on the waiting time of these urgent patients, and to our view, there is no need for a living-related liver program for FHF in resident patients within the Eurotransplant area. In recent series of the literature, creatinine levels, body mass index, recipient age and history of life support have been established as significant risk factors for post-LT death in FHF patients[5,18].

At least two patients of this series developed neurological lesions during the peri-transplantation period. This is certainly due to intracranial hypertension, a frequent complication of FHF, promoted by brain edema and increased blood flow[2]. We demonstrated that during LT for FHF the dissection and reperfusion phases are particularly at risk of intracranial hypertension[22]. On the contrary, the anhepatic phase, even if prolonged, may be associated with good neurologic outcome[23]. The development of neurological lesions during the peri-transplantation period has also been reported in larger series[18,24].

In conclusion, this series confirmed that long-term outcome of patients transplanted for non-acetaminophen FHF may be excellent. As the quality of life of these patients is also particularly good, these results proved that LT for FHF is clearly justified, despite a lower graft survival compared to LT for other liver diseases.

| 1. | Detry O, Honoré P, Meurisse M, Jacquet N. Management of fulminant hepatic failure. Acta Chir Belg. 1998;98:235-240. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Detry O, De Roover A, Honore P, Meurisse M. Brain edema and intracranial hypertension in fulminant hepatic failure: pathophysiology and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7405-7412. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Arkadopoulos N, Detry O, Rozga J, Demetriou AA. Liver assist systems: state of the art. Int J Artif Organs. 1998;21:781-787. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bismuth H, Samuel D, Gugenheim J, Castaing D, Bernuau J, Rueff B, Benhamou JP. Emergency liver transplantation for fulminant hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:337-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Barshes NR, Lee TC, Balkrishnan R, Karpen SJ, Carter BA, Goss JA. Risk stratification of adult patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure. Transplantation. 2006;81:195-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, Reisch JS, Schiødt FV, Ostapowicz G, Shakil AO. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2005;42:1364-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1326] [Cited by in RCA: 1295] [Article Influence: 61.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiødt FV, Larson A, Davern TJ, Han SH, McCashland TM, Shakil AO, Hay JE, Hynan L. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1562] [Cited by in RCA: 1483] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schiodt FV, Atillasoy E, Shakil AO, Schiff ER, Caldwell C, Kowdley KV, Stribling R, Crippin JS, Flamm S, Somberg KA. Etiology and outcome for 295 patients with acute liver failure in the United States. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bernal W, Wendon J, Rela M, Heaton N, Williams R. Use and outcome of liver transplantation in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Hepatology. 1998;27:1050-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lejeune G, Limet R, Meurisse M, Honoré P, Defraigne JO, Detry O, De Roover A. History of solid organ transplantation at the University of Liège. Acta Chir Belg. 2003;103:32-36. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Detry O, De Roover A, Delwaide J, Coimbra C, Kaba A, Joris J, Damas P, Meurisse M, Honoré P. Living related liver transplantation in adults: first year experience at the University of Liège. Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104:166-171. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Trey C, Davidson CS. The management of fulminant hepatic failure. Prog Liver Dis. 1970;3:282-298. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bernuau J, Goudeau A, Poynard T, Dubois F, Lesage G, Yvonnet B, Degott C, Bezeaud A, Rueff B, Benhamou JP. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in fulminant hepatitis B. Hepatology. 1986;6:648-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | O'Grady JG, Alexander GJ, Hayllar KM, Williams R. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:439-445. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Belghiti J, Noun R, Sauvanet A. Temporary portocaval anastomosis with preservation of caval flow during orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Surg. 1995;169:277-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Belghiti J, Noun R, Sauvanet A, Durand F, Aschehoug J, Erlinger S, Benhamou JP, Bernuau J. Transplantation for fulminant and subfulminant hepatic failure with preservation of portal and caval flow. Br J Surg. 1995;82:986-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Detry O, Honoré P, Jacquet N, Meurisse M. Management of recipients of hepatic allografts harvested from donors with malignancy diagnosed shortly after transplantation. Clin Transplant. 1998;12:579-581. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Farmer DG, Anselmo DM, Ghobrial RM, Yersiz H, McDiarmid SV, Cao C, Weaver M, Figueroa J, Khan K, Vargas J. Liver transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure: experience with more than 200 patients over a 17-year period. Ann Surg. 2003;237:666-675; discussion 675-676. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Bismuth H, Samuel D, Castaing D, Williams R, Pereira SP. Liver transplantation in Europe for patients with acute liver failure. Semin Liver Dis. 1996;16:415-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ascher NL, Lake JR, Emond JC, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure. Arch Surg. 1993;128:677-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McCashland TM, Shaw BW, Tape E. The American experience with transplantation for acute liver failure. Semin Liver Dis. 1996;16:427-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Detry O, Arkadopoulos N, Ting P, Kahaku E, Margulies J, Arnaout W, Colquhoun SD, Rozga J, Demetriou AA. Intracranial pressure during liver transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure. Transplantation. 1999;67:767-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Detry O, De Roover A, Delwaide J, Hans MF, Canivet JL, Meurisse M, Honoré P. 60 h of anhepatic state without neurologic deficit. Transpl Int. 2006;19:769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Zhou T