INTRODUCTION

The cause of mechanical small bowel intestinal obstruction includes gallstones, foreign bodies, bezoars, tumors, adhesions, congenital abnormity, intussusceptions, and volvulus[1]. Among these causes, a gallstone-induced intestinal obstruction is also referred to as a “gallstone ileus”. Gallstone ileus is a rare and potentially serious complication of cholelithiasis[2]. It accounts for 1%-4% of all cases of mechanical intestinal obstruction, but for up to 25% of those in patients over 65 years of age with a female to male ratio of 3.5-6.0:1[3-6]. The morbidity and mortality rate of gallstone ileus remain very high, partly because of misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis[7]. Thus, early diagnosis and prompt treatment could reduce the mortality rate. Here, we report two cases of gallstone ileus and review the literature of this rare disease.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

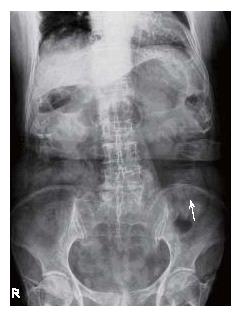

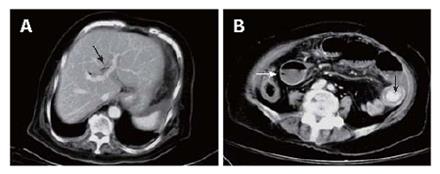

A 78-year old woman presented to our emergency department (ED) with a 2-d history of vomiting and epigastric pain. She had a past medical history of hypertension and underwent a hystectomy for a myoma at the age of 38. On physical examination, her abdomen was mildly distended without tenderness or rebound or Murphy’s sign. The white blood count was 16 630/μL with 87.6% neutrophils, blood urea nitrogen 67 mg/dL, 2.3 mg/dL creatinine 2.3 mg/dL and k 2.7 mmol/L. The other tests were unremarkable. A plain abdominal film demonstrated mildly dilated bowel loops, but a vague stone was not identified in the left iliac fossa (Figure 1). The diagnostic impression was ileus due to adhesions. Abdominal ultrasound (US) disclosed a shrunken gallbladder with internal air, but without stones. An abdominal computed tomography was performed, demonstrating air in the biliary tree (Figure 2A). Moreover, an ectopic stone impacted in the jejunal lumen was seen in the left lower quadrant along with dilatation of the proximal small bowel (Figure 2B). The diagnosis of gallstone ileus was made and she underwent an emergent laparotomy. At operation a small shrunken gallbladder with dense adhesion to the stomach was found. After lysis of adhesion, a fistula between the gallbladder dome and the lesser curvature of gastric antrum was confirmed. Moreover, a stone was palpated in the jejunum about 140 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz causing total obstruction of the lumen. When the jejunum was opened, the stone was laminated and cylinder shaped, measuring 3 cm × 3 cm × 2 cm in diameter. Enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy and repair of the cholecystogastric fistula were performed. The pathology showed chronic cholecystitis and a fistula walled by granulation tissue. The postoperative course was uneventful except for mild wound infection, and she remained in good health after one-year follow-up.

Figure 1 Plain abdominal film showing a vague stone not identified in the left iliac fossa (arrow).

Figure 2 Abdominal computed tomography scan showing air in the biliary tree (arrow) (A) and an ectopic stone (arrow) impacting the jejunal lumen accompanying dilatation of proximal small bowel loops (white arrow) (B).

Case 2

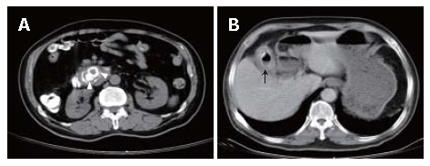

A 76-year old man was brought to our ED because of epigastric pain for one week. He denied any history of abdominal surgery or biliary disease. On physical examination his abdomen was soft, but tender in the epigastric area. Laboratory tests were unremarkable. Abdominal X-ray showed two round calcified stones in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen (Figure 3). An EGD disclosed a deep hole in the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb, but no stone was identified. Fistulography confirmed the presence of a cholecystoduodenal fistula. An abdominal CT was performed, showing two round calcified stones located in the proximal third portion of the duodenum causing dilatation of proximal bowel lumen (Figure 4A). There was a thickened wall gallbladder with internal gas and small calcified content was also discovered (Figure 4B). Duodenoscopy was performed again, showing two stones impacted in the proximal third portion of the duodenum. We attempted to catch the stones with a Dormia basket, but failed because of their larger size. Therefore, he was referred to our department of surgery for emergent laparotomy. Laparotomy displayed that the gallbladder was adhered to the duodenum accompanying a cholecystoduodenal fistula. A large black stone, measuring 5 cm × 4 cm × 3 cm in diameter, impacted the proximal third portion of the duodenum. No other stones were found in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy, duodenorrhaphy, feeding jejunostomy, and repair of the cholecystoduodenal fistula were performed. Microscopically, the gallbladder showed cholelithiasis with acute and chronic inflammation and a fistula walled by fibrous and granulation tissue. The postoperative course was complicated by a wound infection, and he was discharged 2 mo later.

Figure 3 Plain abdominal film showing two round calcified stones in the right upper quadrant of abdomen (arrow).

Figure 4 Abdominal computed tomography scan showing two round calcified stones impacting the proximal third portion of the duodenum (arrowhead) (A) and a thickened wall gallbladder with internal air and small calcified content (arrow) (B).

DISCUSSION

Gallstone is a common disease with a prevalence in 10% of the adult population in the United States[8]. However, it is only symptomatic in 20%-30% of patients, with biliary colic being the most common symptom[9]. The most common complications of gallstone disease include acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, choledocholithiasis with or without cholangitis, and a gangrenous gallbladder. Other uncommon complications include Mirizzi syndrome, cholecystocholedochal fistula, and gallstone ileus[2,10].

The term “gallstone ileus” was first coined by Bartolin in 1654 and referred to the mechanical intestinal obstruction due to impaction of one or more large gallstones within the GI tract. Biliary-enteric fistula is the major pathologic mechanism of gallstone ileus[11]. The gallstone enters the GI tract through a fistula between a gangrenous gallbladder and the GI tract. Occasionally a stone may enter the intestine through a fistulous communication between the common bile duct and the GI tract. Although the gallstone can impact anywhere in the GI tract, its size should be at least 2 cm to 2.5 cm in diameter to cause obstruction[6]. Reisner and Cohen[5] reviewed 1001 cases of gallstone ileus and reported that the most common locations of impaction of gallstone are the terminal ileum and the ileocecal valve because of the anatomical small diameter and less active peristalsis. They also found that the less common locations for impaction are the jejunum, the ligament of Treitz, and the stomach, while the duodenum and colon are the rare locations for impaction[5].

The clinical manifestations of gallstone ileus are variable and usually depend on the site of obstruction. The onset may be manifested as acute, intermittent or chronic episodes[12]. The most common symptoms include nausea, vomiting and epigastric pain. Moreover, a small portion of patients may present with hematemesis secondary to duodenal erosions. Laboratory studies may show an obstructive pattern with elevated values of bilirubin and alkaline phosphophatase.

The diagnosis of gallstone ileus is difficult, usually depending on the radiographic findings. In 50% of cases the diagnosis is often only made at laparotomy[5]. The classic Rigler’s triad of radiography includes mechanical bowel obstruction, pneumobilia, and an ectopic gallstone within bowel lumen. However, air in the gallbladder is also a frequent finding in gallstone ileus[13]. Plain abdominal films usually show non-specific findings because only 10% of gallstones are sufficiently calcified to be visualized radiographically. For example, in our first case, although the ectopic gallstone appeared on the initial plain abdominal film, it was misdiagnosed as fecal material due to insufficient calcification. But in our second case, two gallstones were definitely identified on a plain abdominal film. Upper or lower GI barium studies occasionally identify the site of obstruction or fistula. Abdominal US is useful to confirm the presence of cholelithiasis and may identify fistula, if present[14]. Abdominal CT becomes the more important modality in diagnosing gallstone ileus because of its better resolution. By comparing with plain abdominal film and abdominal US, it can provide a more rapid and specific diagnosis in emergency use. Lassandro et al[15] compared the clinical value of plain abdominal film, abdominal US and abdominal CT in diagnosing 27 cases of gallstone ileus, and found that the Rigler’s triad presents 14.81% in plain abdominal film, 11.11% in abdominal US, and 77.78% in abdominal CT, respectively. Additionally, Yu et al[16] studied the value of abdominal CT in the diagnosis and management of gallstone ileus and concluded that the abdominal CT offers crucial evidence not only for the diagnosis of gallstone ileus but also for decision making in management strategy[16]. Rarely, laparoscopy is used to diagnose this disease[17].

Gallstone ileus usually requires emergent surgery to relieve intestinal obstruction. Bowel resection is only indicated when there is intestinal perforation or ischemia[18]. There is no uniform surgical procedure for this disease because of its low incidence. Although enterolithotomy alone remains the popular operative method in most reports, the one-stage procedure composed of enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy and repair of fistula is necessary, if indicated[19]. Tan et al[20] compared the two surgical strategies of enterolithotomy alone and enterolithotomy with cholecystectomy for the emergent treatment of gallstone ileus, and concluded that both procedures are safe with no mortality, but the better surgical option is enterolithotomy. Doko et al[21] agreed that the one-stage procedure should be reserved only for highly selected patients with absolute indications. Recently, laparoscopy-guided enterolithotomy has become the preferred surgical approach in treating gallstone ileus[22]. Additionally, the non-surgical treatment of gallstone ileus has been suggested, including endoscopic removal and shockwave lithotripsy, but this depends on the location of obstruction[23,24]. In our second case, the two stones were detected by radiography preoperatively, but they were not found on the first EGD. The second duodenoscopy revealed two stones impacting the third portion of the duodenum. We attempted to remove them endoscopically, but failed due to their larger size.

The prognosis of gallstone ileus is usually poor and worsens with age. Previous studies reported that the mortality rate is 7.5%-15%[5,6], largely due to delayed diagnosis and concomitant conditions such as cardiorespiratory disease, obesity and diabetes mellitus. The postoperative recurrence rate of gallstone ileus is 4.7% and only 10% of patients require secondary biliary surgery for recurrent biliary symptoms[5,25].

In conclusion, gallstone ileus is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction. It must be considered in intestinal obstruction patients with a past history of gallstone, especially in elderly females. Abdominal CT is the preferred modality because of its rapid diagnosis of gallstone ileus. Surgical treatment is emergent when the radiological finding is highly or even suspicious or confirmed.