Published online Nov 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i42.5659

Revised: August 21, 2007

Accepted: October 14, 2007

Published online: November 14, 2007

A 54-year-old man presented with rectal pain and bleeding secondary to ulcerated, necrotic rectal and cecal masses that resembled colorectal carcinoma upon colonoscopy. These masses were later determined to be benign amebomas caused by invasive Entamoeba histolytica, which regressed completely with medical therapy. In Western countries, the occurrence of invasive protozoan infection with formation of amebomas is very rare and can mistakenly masquerade as a neoplasm. Not surprisingly, there have been very few cases reported of this clinical entity within the United States. Moreover, we report a patient that had an extremely rare occurrence of two synchronous lesions, one involving the rectum and the other situated in the cecum. We review the current literature on the pathogenesis of invasive E. histolytica infection and ameboma formation, as well as management of this rare disease entity at a western medical center.

- Citation: Hardin RE, Ferzli GS, Zenilman ME, Gadangi PK, Bowne WB. Invasive amebiasis and ameboma formation presenting as a rectal mass: An uncommon case of malignant masquerade at a western medical center. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(42): 5659-5661

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i42/5659.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i42.5659

Amebiasis is an infectious disease caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. Infection rarely, but potentially may evolve into invasive colitis and formation of ameboma, which can closely resemble colorectal carcinoma. In general, the clinical spectrum of colorectal amebiasis ranges from asymptomatic carrier to severe fulminant necrotizing colitis with bleeding and perforation[1]. As previously reported, focal ileocolonic intussusceptions from ameboma formation serving as the lead point, although rare, can occur[2].

The experience with invasive amebiasis is largely from endemic countries. From documentation dating back to 1933, to date 2970 cases of invasive amebiasis have been reported in the United States, mostly comprising recent immigrants from Mexico, Central and South America, plus Asians and Pacific Islanders[3]. With increasing patterns of immigration and travel in and out of the US, continued recognition of this disease is required. Therefore, the roles of the gastroenterologist and surgeon are to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion in patients at increased risk for this disease entity, and to distinguish this from other more common causes of gastrointestinal masses, as well as instituting appropriate therapy. In this report, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment of this rare clinical entity from a western medical center are reviewed.

A 54-year-old man of Middle Eastern decent, without significant medical history, presented to a community hospital complaining of rectal pain and bleeding for about 2 d. The patient described the pain as constant, without aggravating or alleviating factors. In addition, the patient complained of constipation that led to mild, crampy abdominal pain. He denied nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or fever. The patient also denied any history of weight loss. Pertinent to the patients' presentation was that he had no history of recent travel abroad, anoreceptive intercourse, or family history of carcinoma.

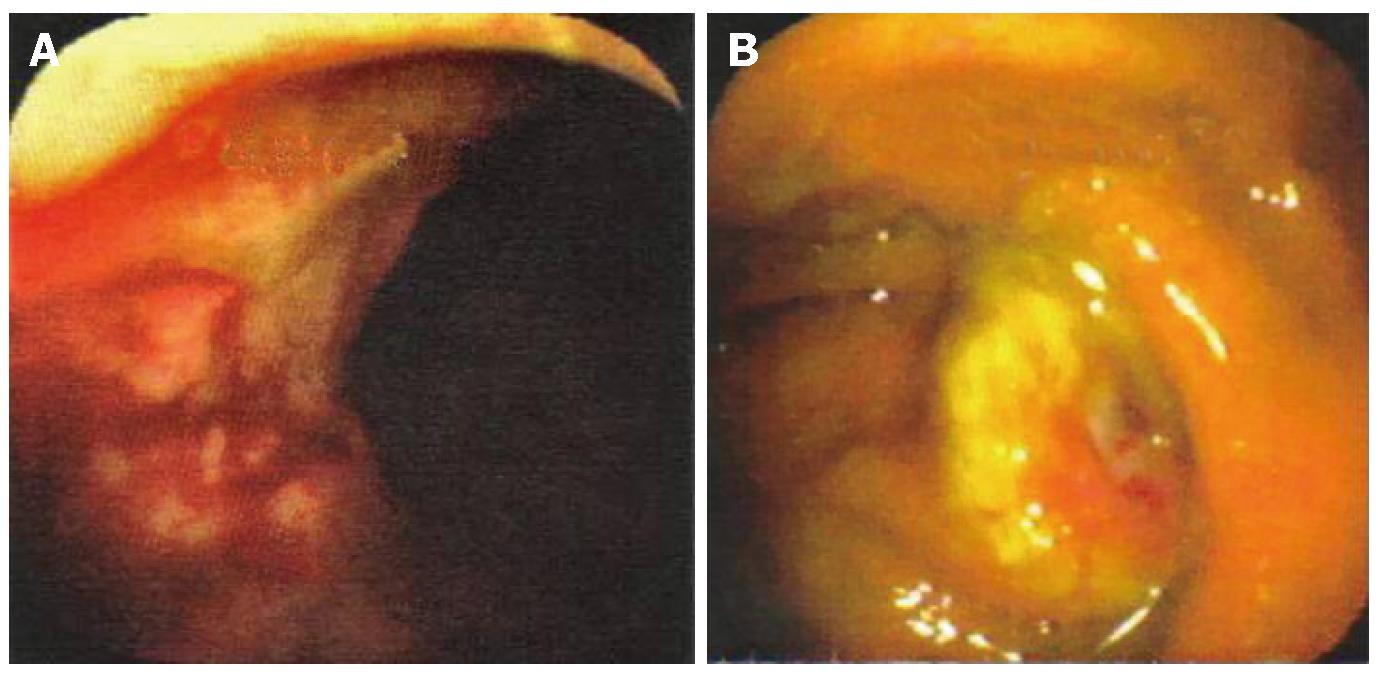

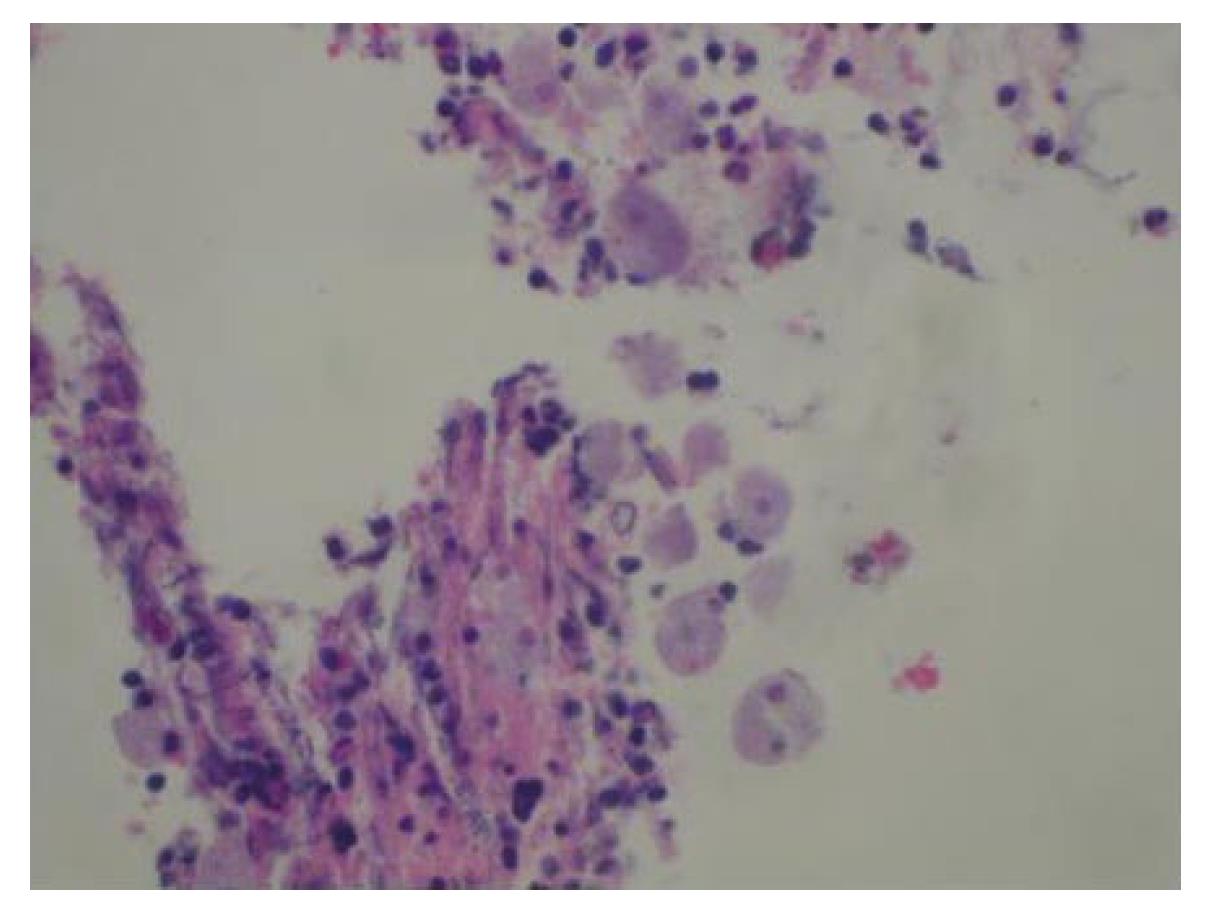

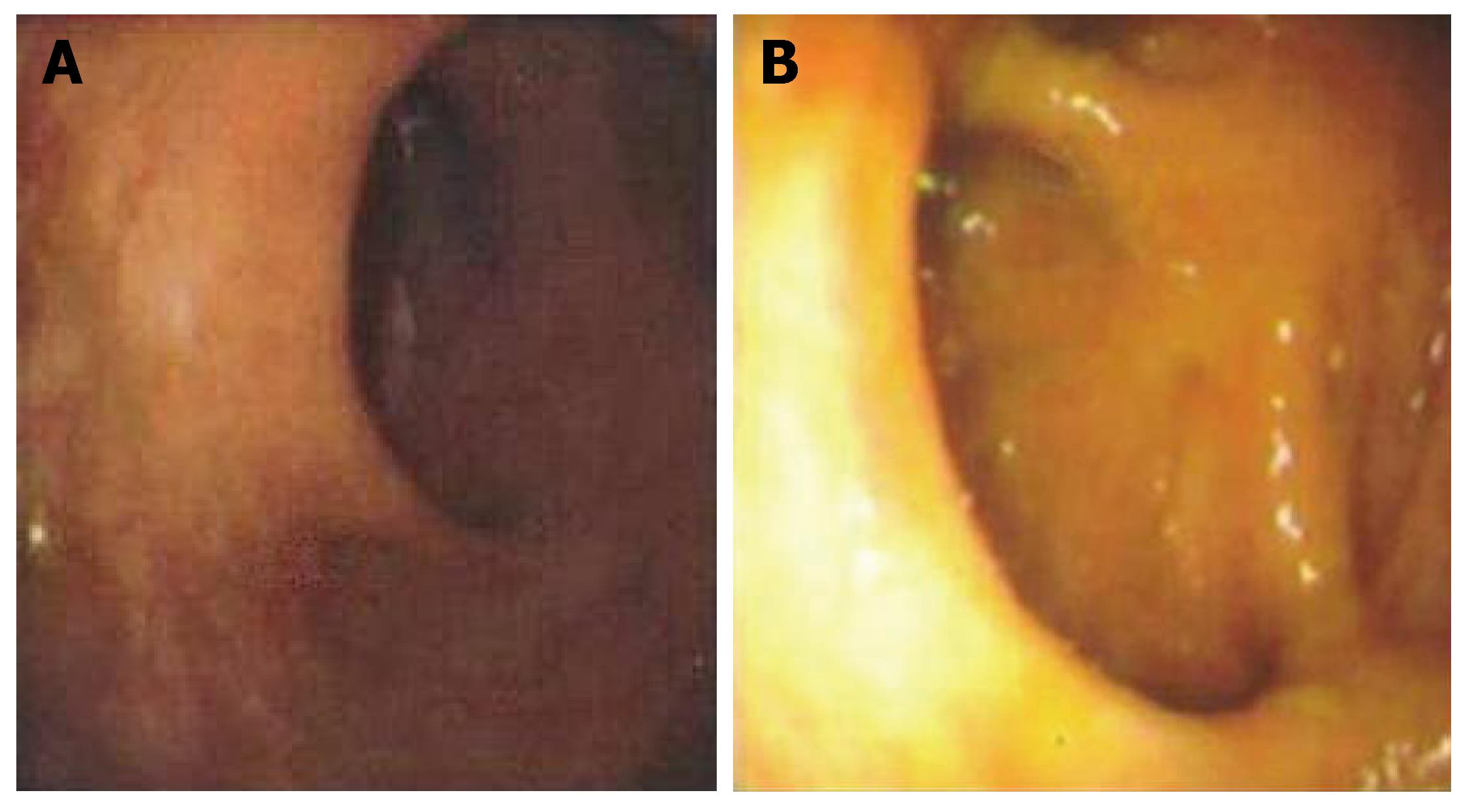

Physical examination revealed a healthy, well-nourished man who was normothermic with normal hemodynamic parameters. His abdominal examination was unremarkable: soft and non-tender, without any appreciable organomegaly. External anal inspection was normal. Rectal examination revealed a large, firm mass in the left lateral position, about 3 cm from the anal verge, with gross blood. Rigid proctosigmoidoscopy was performed, which revealed an ulcerated mass starting at the dentate line (Figure 1A). The surface of the lesion appeared necrotic and highly suggestive of carcinoma, which was the preliminary diagnosis. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse, non-specific thickening of the rectal wall without intra-abdominal pathology. A colonoscopy was performed that demonstrated an additional ulcerated lesion involving the cecum (Figure 1B). Both lesions were biopsied and were consistent with lymphocytic colitis. Importantly, protozoan organisms, consistent with amebiasis were identified (Figure 2). Serology for Entamoeba histolytica infection was also confirmed. The rectal and cecal lesions were determined to be amebomas as a result of invasive amebiasis. The patient was given a course of oral antibiotic therapy with metronidazole for 4 wk, with complete resolution of his symptoms. A follow-up surveillance colonoscopy and CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated complete regression of both the rectal and cecal lesions (Figure 3A and B).

The intestinal protozoan parasite E. histolytica is the causative organism responsible for human amebiasis and amebic dysentery. Of epidemic proportions, it afflicts millions of people worldwide in developing countries, and about 40000-100000 people die annually from this disease[4]. Transmission is mostly by ingestion of contaminated food and water; however, venereal transmission via the fecal-oral route can occur[5].

Trophozoites are responsible for invasive disease and may lead to colonic mucosal ulceration. The gastrointestinal tract and liver are the two main organ systems affected by the parasite. Rarely, patients with long-standing infection develop ulcerative, exophytic, inflammatory masses that are indistinguishable from carcinomas and can become a considerable size, reportedly up to 15 cm in diameter[5]. Such lesions are referred to as amebomas. Moreover, colonic amebomas may present with synchronous amebic liver abscesses, which can also masquerade as advanced carcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract.

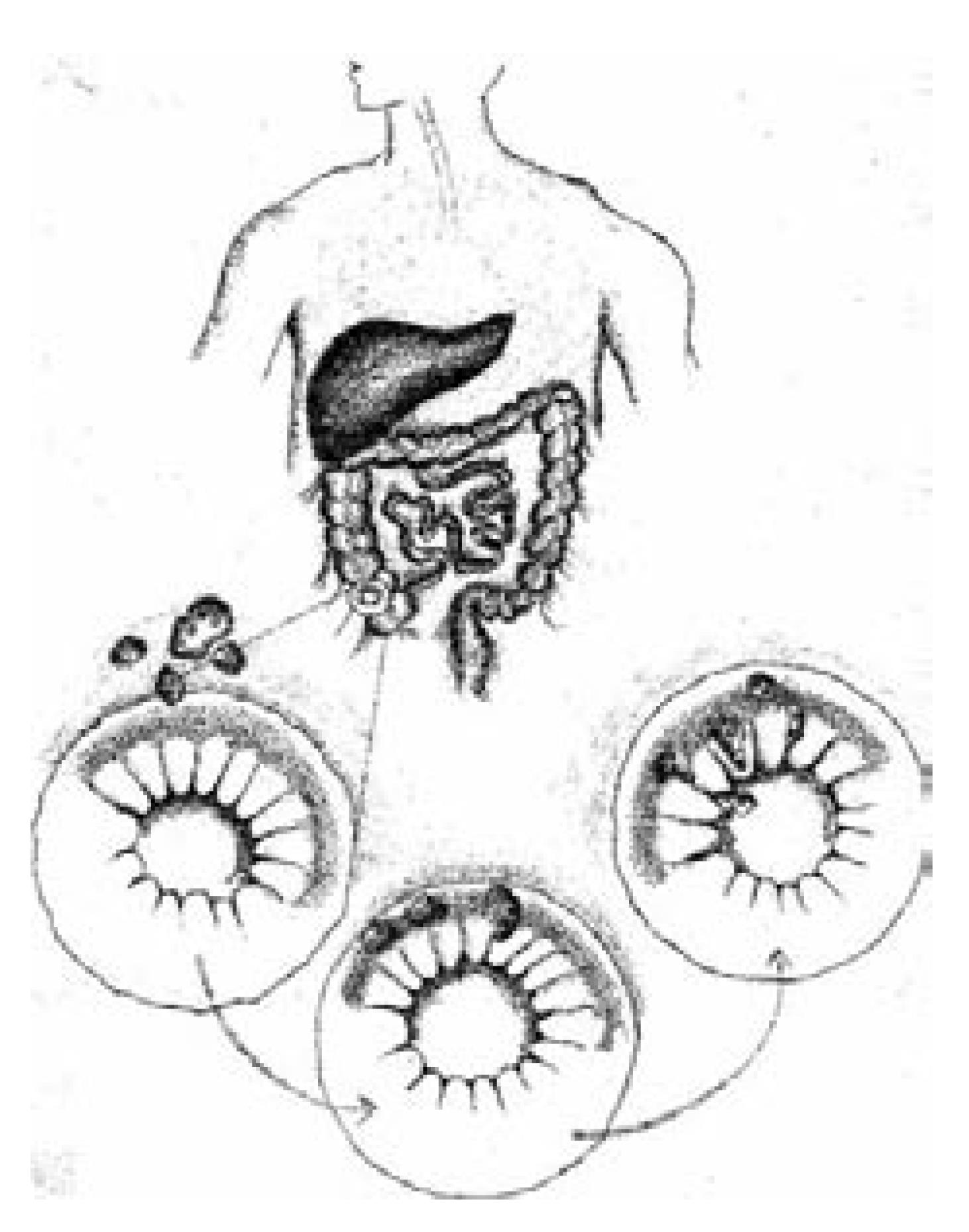

Amebomas result from the formation of annular colonic granulation tissue at single or multiple sites, usually within the cecum or ascending colon (Figure 4). Formation of an ameboma is an uncommon complication of invasive amebiasis. It occurs in 1.5% of all cases with invasive amebiasis[6]. Amebomas usually develop in the untreated or inadequately treated patients with amebiasis years after the attack of dysentery[5]. The current report is atypical, as our patient denied any history of antecedent symptoms suggestive of dysentery or foreign travel. Clinically, amebomas can also cause obstructive symptoms. Patients may also present with diarrhea or constipation and associated systemic symptoms, including weight loss and fever. In areas in which infection is prevalent, crampy abdominal pain plus a palpable mass usually suggests the diagnosis. In contrast, in western countries, a similar presentation alternatively raises suspicion of malignancy. The differential diagnosis for this clinical picture may also include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), lymphoma, enterocolitis and intestinal tuberculosis[6]. In most cases in western countries, a diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma or IBD is considered more likely than a parasitic infection. Interestingly, there has been only a single E. histolytica outbreak in the United States, which occurred in Chicago in 1933 when sewage pipes contaminated tap water pipes in a hotel, which led to 800 cases of amebiasis[3].

The pathological range of amebic colitis extends from mucosal thickening with discrete ulcer formation, separated by regions of normal colonic mucosa, to diffusely inflamed and edematous mucosa. Severe forms of invasive amebiasis may progress to frank necrosis and perforation of the intestinal wall[3]. These findings are grossly similar to those found with IBD, in particular Crohn's colitis. Parasitic colitis results when the trophozoite penetrates the intestinal mucosal layer. Subsequent invasion occurs as a result of epithelial, neutrophil and lymphocyte cellular destruction by trophozoites[7].

The standard method for diagnosis of intestinal amebiasis is examination of stools by microscopy. However, the reported sensitivity of this method for identifying amebic organisms ranges from 25% to 60%[4]. False-positive results may also occur because E. histolytica is morphologically identical to non-pathological species, namely, Entamoeba dispar and Entameba moshkovskii[4]. Currently, more sensitive and specific methods, including antigen detection in stools and serum, and polymerase chain reaction techniques are now utilized[4].

The primary treatment for amoebic colitis is oral metronidazole therapy. Affected patients should be treated with metronidazole for 5-10 d. Longer intervals of therapy may be warranted in cases with ameboma formation, as in our patient. Treatment with metronidazole may be followed by a luminal agent such as paromomycin, iodoquinol or diloxanide furoate for 5-20 d to eradicate colonization[4]. Surgical intervention is rarely indicated except for rare instances of acute necrotizing colitis with bowel perforation, or if the patient fails to respond to anti-amebic therapy. Although amebiasis is a clinical entity rarely encountered in developed western countries, it should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with bloody diarrhea and a colon mass, with a history of dysentery along with travel to endemic areas. A high index of suspicion is required for appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Unfortunately, there are no pathognomonic radio-graphic or endoscopic features suggestive of invasive ameboma formation; therefore, pathologic confirmation is crucial, as well as appropriate serology. Multiple biopsies may often be required to confirm the diagnosis. Two important caveats are essential to consider when managing patients with invasive amebomas: (1) follow up sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy after completion of medical therapy to assure complete resolution of disease; and (2) persistent disease or incomplete regression should raise the suspicion for an underlying malignancy as the two entities may coexist[1].

In summary, the equivocal clinical symptoms (i.e., pain, bleeding and obstruction) that differentiate invasive amebiasis presenting as an ameboma from carcinoma may prove problematic. Notwithstanding, in a high-risk patient, clinical suspicion is warranted to assure appropriate diagnostic evaluation. Differentiating amebiasis from colorectal carcinoma by endoscopy with biopsy, serology, and other novel modes of antigen detection provides essential information. Therapeutic intervention with oral anti-parasitic medications rather than surgical management should then occur.

| 1. | Ooi BS, Seow-Choen F. Endoscopic view of rectal amebiasis mimicking a carcinoma. Tech Coloproctol. 2003;7:51-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Steer D, Clarke DL, Buccimazza I, Thomson SR. An unusual complication of intestinal amoebiasis. S Afr Med J. 2005;95:845. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Stanley SL. Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 915] [Cited by in RCA: 831] [Article Influence: 36.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ng DC, Kwok SY, Cheng Y, Chung CC, Li MK. Colonic amoebic abscess mimicking carcinoma of the colon. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12:71-73. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Simşek H, Elsürer R, Sökmensüer C, Balaban HY, Tatar G. Ameboma mimicking carcinoma of the cecum: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:453-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Misra SP, Misra V, Dwivedi M. Ileocecal masses in patients with amebic liver abscess: etiology and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1933-1936. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA. Amebiasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1565-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 640] [Cited by in RCA: 576] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lu W