Published online Jan 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i4.643

Revised: November 3, 2006

Accepted: December 14, 2006

Published online: January 28, 2007

We report a case of pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis, and inflammation in the neo-terminal ileum proximal to the pouch, developed after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. A 35-year old female presented with fever and abdominal pain five weeks after ileostomy closure following proctocolectomy. Computed tomography showed collection of feces in the pouch and proximal ileum. A drainage tube was placed in the pouch perianally, and purulent feces were discharged. With antibiotic treatment, her symptoms disappeared, but two weeks later, she repeatedly developed fever and abdominal pain along with anal bleeding. Pouchscopy showed mucosal inflammation in both the pouch and the pre-pouch ileum. The mucosal cytokine production was elevated in the pouch and pre-pouch ileum. With antibiotic and corticosteroid therapy, her symptoms were improved along with improvement of endoscopic inflammation and decrease of mucosal cytokine production. The fecal stasis with bacterial overgrowth is the major pathogenesis of pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis in our case.

- Citation: Iwata T, Yamamoto T, Umegae S, Matsumoto K. Pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis developed after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(4): 643-646

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i4/643.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i4.643

Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis has become the surgical procedure of choice for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC)[1-3]. Pouchitis is the most common complication following restorative proctocolectomy for UC[1-5]. Patients with UC may develop inflammation in the neo-terminal ileum (pre-pouch ileum) proximal to the pouch, so called pre-pouch ileitis. So far, there has been only one study reporting the details of pre-pouch ileitis. Bell and colleagues[6] retrospectively investigated the clinicopathological characteristics of pre-pouch ileitis using their pouch database, however the pathogenesis of pre-pouch ileitis is unknown. We have recently experienced one patient in whom both pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis developed after restorative proctocolectomy for UC. The purpose of this article is to report the case of our patient, and to discuss the pathogenesis of pre-pouch ileitis based on the clinicopathological and immunological findings.

In July 2005, we received a 35-year old female with a six-year history of UC requiring surgical treatment. Small bowel follow-through, barium enema and ileocolonoscopy with histological examinations confirmed UC but not Crohn’s disease. She had a history of allergy to sulfasalazine and mesalazine. She was treated with long-term corticosteroid therapy, and the cumulative dose of prednisolone administered before operation was more than 20 g. Selective granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis therapy was not effective. She had no history of extraintestinal manifestations. Endoscopically, the extent of disease was pancolitis without backwash ileitis. The indication for surgery was steroid-dependency and chronic continuous disease. A laparoscopic-assisted proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal canal anastomosis was performed. The J-shaped pouch (15 cm in length) was constructed using a linear stapler. A stapled ileo-anal canal anastomosis was performed at approximately 2 cm from the dentate line. There was no difficulty in mobilizing the ileal pouch sufficiently to achieve a tension-free anastomosis. The covering ileostomy was constructed to protect the anastomosis. After operation, she developed no serious complications, and was doing well with her ileostomy. Histological diagnosis of the colectomy specimen was UC, and there were no findings of inflammation in the terminal ileum.

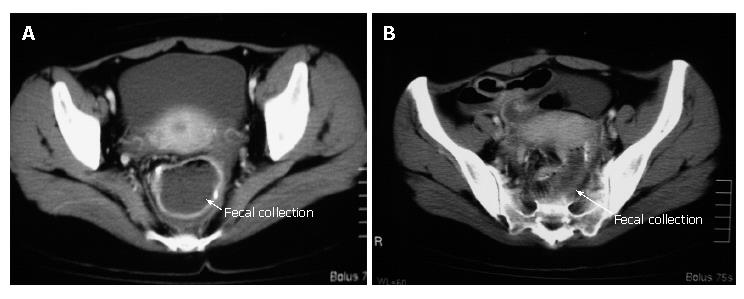

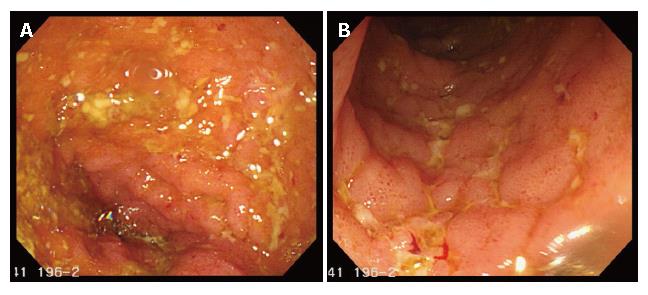

Before ileostomy closure, a pouchgram, pouchscopy with biopsy, and manometric study were performed. The pouchgram showed no findings of anastomotic leak, fistulae and strictures, decreased pouch compliance, a long efferent loop, or decreased pouch emptying. Both endoscopically and histologically, there were no findings of inflammation in the pouch and proximal ileum. In the manometric study, the resting anal pressure was 42 mmHg compared with 65 mmHg before pouch construction. The squeezing pressure was 110 mmHg compared with 128 mmHg before pouch construction. In March 2006, she had her ileostomy closed. Postoperatively, she was doing well, and on a normal diet. However, five weeks after operation, she developed high fever (40°C) and severe abdominal pain. Retrospectively, the number of defecations did not change (7-10 times/d), but the fecal volume on each defecation remarkably decreased for several days before her symptoms occurred. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a massive collection of feces in the pouch and proximal ileum (Figure 1). A drainage tube was placed in the pouch perianally, and a large amount of purulent feces were discharged. In fecal culture, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli O157, Yersinia, Vibrio and Clostridium difficile were negative, whereas Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus were positive. She was managed with total parenteral nutrition in combination with intravenous antibiotic administration (imipenem, 1.0 g/d for one week). Her symptoms disappeared after the five-day drainage of the feces, and she was back on a normal diet. However, two weeks later, she repeatedly presented with fever (40°C) and severe abdominal pain along with mild anal bleeding. Pouchscopy showed inflammatory conditions such as edema, granularity, friability, loss of vascular pattern, and erosions in both the pouch and the pre-pouch ileum (continuous 30 cm proximal to the pouch, Figure 2). The inflammation was milder more proximally. Biopsies were taken for histological examination and mucosal cytokine measurement. Histologically, moderate leukocyte infiltration without crypt abscess formation was observed in both the pouch and the pre-pouch ileum. According to the pouchitis disease activity index by Sandborn[5], her score was 12, and she was diagnosed as having pouchitis (≥ 7 points). Antibiotics (cefmetazone sodium, 2.0 g/d for one week), and prednisolone (30 mg/d for one week) were administered intravenously. Her symptoms were rapidly improved, and pouchscopy after the one-week treatment revealed improvement in mucosal inflammation. Thereafter, predonisolone was orally given (15 mg/d for two weeks, and then 10 mg/d for two weeks). Four months after ileostomy closure following pouch operation, she was doing well with normal bowel function (defecation, 5-7 times/d; soiling, 1 time/2 wk).

Using the biopsy specimens obtained during pouchscopy, the mucosal cytokine (interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) levels were measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as previously reported (Table 1)[7]. In this patient, the mucosal cytokine levels were examined before ileostomy closure, at the time of diagnosis of pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis, and one week after the treatment for inflammation, and compared with those in 28 patients without pouchitis or pre-pouch ileitis three months after ileostomy closure following ileal pouch construction for UC in our previous study[7]. At the diagnosis of pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis, the mucosal cytokine levels were remarkably elevated in both the pouch and the pre-pouch ileum compared with those before ileostomy closure. White blood cell (WBC) count was 12 300/mm3, platelet cont was 443 000/mm3, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 19.34 mg/dL. After the one-week administration of antibiotics and prednisolone, the mucosal cytokine levels markedly decreased along with endoscopic improvement of mucosal inflammation. At that time, WBC count was 10 800/mm3, platelet count was 506 000/mm3, and CRP level was 0.09 mg/dL.

| Beforeileostomyclosure | At the diagnosisofpouchitis andpre-pouch ileitis | Aftertreatment | Patients withoutpouchitis orpre-pouch ileitis1 | |

| Pouch (pg/mg of tissue) | ||||

| IL-1β | 25 | 730 | 98 | 34.5 (26-39) |

| IL-6 | 590 | 14 000 | 2700 | 900 (580-1480) |

| IL-8 | 31 | 840 | 290 | 58 (34-76) |

| TNF-α | 10 | 350 | 67 | 38.5 (27-60) |

| Pre-pouch ileum (pg/mg of tissue) | ||||

| IL-1β | 17 | 560 | 91 | 10.5 (5-22) |

| IL-6 | 600 | 17 000 | 3600 | 570 (420-720) |

| IL-8 | 22 | 710 | 190 | 19.5 (10-41) |

| TNF-α | 13 | 270 | 82 | 12 (5-18) |

The etiology of pouchitis is still unknown. A variety of factors such as fecal stasis, bacterial overgrowth, immune alternation, bile acid toxicity, short-chain fatty acid deficiency, and ischemia may affect the development of pouchitis[4,8,9]. In our research[7], to examine the impact of the fecal stream and stasis on immunological reactions in the pouch and proximal ileum, mucosal cytokine production was measured before and after ileostomy closure following proctocolectomy for UC. No patients developed pouchitis or pre-pouch ileitis during the study period. We found that immunological reactions in the pouch occurred soon after ileostomy closure, and continued thereafter[7]. In contrast, cytokine production was not elevated in the proximal ileum, where the fecal stasis does not often occur. Thus, the fecal stasis may play an important part in the pathogenesis of immunological reactions in the pouch[7].

Bell and colleagues[6] reported that 15 (2.6%) of 571 inflammatory bowel disease patients undergoing restorative proctocolectomy developed pre-pouch ileitis. However, this incidence may be underestimated because their study was retrospective, and the pre-pouch ileum was not routinely examined. The median age of the 15 patients (eight females) was 36 years, and the median duration from pouch construction to diagnosis of pre-pouch ileitis was three years. The most common clinical presentations were frequency of defecation (40%) and bowel obstruction (40%). Preoperatively, backwash ileitis was observed in 18% of the patients, and 27% had a history of extraintestinal manifestations. All patients had continuous disease from the neo-terminal ileum-pouch junction for a distance of 1 cm to more than 50 cm proximally becoming milder more proximally. Concomitant pouchitis was observed in 47% of the patients. Nine patients had narrowing of the lumen in the pre-pouch ileum, and in two of these there was a severe stricture. One patient had a fistula from the pre-pouch ileum to the vagina. Eleven patients with symptoms were treated, of whom eight required surgery (resection in six, strictureplasty in one, defunctioning ileostomy in one).

In the study by Bell and colleagues[6], there were no statements about the pathogenesis of pre-pouch ileitis. Only half of their patients with pre-pouch ileitis had concomitant pouchitis. Several patients presented with tight stricture, deep ulcerations or fistula. We suspect that these patients may have Crohn’s disease, although the histological diagnosis based on the colectomy specimen was confirmed as UC[6]. Wolf et al[10] reported that afferent limb ulcers predict Crohn’s disease in patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. In our case, findings suggesting Crohn’s disease were not observed.

The pathogenesis of pre-pouch ileitis is also unknown. Our patient developed a massive collection of feces in the pouch and pre-pouch ileum in the early postoperative period after ileostomy closure, which was detected by CT. Before her symptoms (fever and abdominal pain) occurred, the fecal volume remarkably decreased, although the number of defecations did not change. The cause of fecal collection is unknown. Before ileostomy closure, pouchgram showed no evidence of anastomotic strictures, decreased pouch compliance, or decreased pouch emptying. The results in our manometric study were similar to those in patients with normal pouch function after restorative proctocolectomy in the previous study[11]. Although a longer follow-up was necessary, she had neither evacuation problems nor impaired pouch emptying at the time of our report (four months after ileostomy closure). If she had the similar symptoms such as fever and abdominal pain along with a decrease in volume of feces, further studies were needed to examine her pouch function.

In our case, endoscopic and histological features of mucosal inflammation were similar in the pouch and pre-pouch ileum, although the inflammation was milder more proximally. Bell and colleagues[6] also found that the histological findings of pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis are similar. In our institution, mucosal cytokine production is routinely investigated before and after ileostomy closure following restorative proctocolectomy for UC[7]. In this report, at the diagnosis of pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis, the mucosal IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α levels were remarkably elevated in both the pouch and the pre-pouch ileum compared with those before ileostomy closure, which were much higher than those in patients without pouchitis or pre-pouch ileitis in our previous study (Table 1)[7], suggesting that both pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis are associated with increased mucosal cytokine production. There seemed to be no significant difference in cytokine production between pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis. These cytokine levels remarkably decreased after antibiotic and steroid medication. Purulent feces were discharged through a drainage tube placed in the pouch. In fecal culture, E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus were detected, which may have caused severe clinical symptoms such as high fever and abdominal pain.

In conclusion, fecal stasis along with subsequent bacterial overgrowth is the major pathogenesis of both pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis. The pathogenesis may be similar in pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis due to the similar endoscopic, histological and immunological features. Further studies are needed to fully understand the pathogenesis of pouchitis and pre-pouch ileitis after restorative proctocolectomy for UC.

| 1. | Bach SP, Mortensen NJ. Revolution and evolution: 30 years of ileoanal pouch surgery. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:131-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Michelassi F, Lee J, Rubin M, Fichera A, Kasza K, Karrison T, Hurst RD. Long-term functional results after ileal pouch anal restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: a prospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2003;238:433-441; discussion 442-445. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Delaney CP, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Hammel J, Church JM, Hull TL, Senagore AJ, Strong SA, Lavery IC. Prospective, age-related analysis of surgical results, functional outcome, and quality of life after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2003;238:221-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pardi DS, Sandborn WJ. Systematic review: the management of pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1087-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a Pouchitis Disease Activity Index. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:409-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 550] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bell AJ, Price AB, Forbes A, Ciclitira PJ, Groves C, Nicholls RJ. Pre-pouch ileitis: a disease of the ileum in ulcerative colitis after restorative proctocolectomy. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:402-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamamoto T, Umegae S, Kitagawa T, Matsumoto K. The impact of the fecal stream and stasis on immunologic reactions in ileal pouch after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: a prospective, pilot study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2248-2253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sandborn WJ. Pouchitis following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: definition, pathogenesis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1856-1860. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Yantiss RK, Sapp HL, Farraye FA, El-Zammar O, O'Brien MJ, Fruin AB, Stucchi AF, Brien TP, Becker JM, Odze RD. Histologic predictors of pouchitis in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:999-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wolf JM, Achkar JP, Lashner BA, Delaney CP, Petras RE, Goldblum JR, Connor JT, Remzi FH, Fazio VW. Afferent limb ulcers predict Crohn's disease in patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1686-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Morgado PJ, Wexner SD, James K, Nogueras JJ, Jagelman DG. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: is preoperative anal manometry predictive of postoperative functional outcome? Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:224-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Bai SH