Published online Jan 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i4.639

Revised: November 13, 2006

Accepted: December 18, 2006

Published online: January 28, 2007

An 81-year-old Japanese man with jaundice was strongly suspected clinically of having primary sclerosing cholangitis based on clinical examinations and later died of hepatic failure. The entire course of the disease lasted about 10 mo. The autopsy revealed extensive fibrinoid necrosis in the liver, kidney, spleen, pancreas, lung, lymph nodes, and pleura. Particularly extensive fibrinoid necrosis in the portal tracts of the liver induced severe stenoses of the intrahepatic bile ducts, resulting in cholestasis in association with prominent liver injury. There were no findings indicating primary sclerosing cholangitis. The hepatic lesions in this case did not coincide with any known disease including collagen diseases. To clarify the cause of irregular stenoses of the intrahepatic biliary trees on cholangiographic findings, we postulate that some form of immunological derangement might be involved in pathogenesis of fibrinoid necrosis. However, the true etiology remains unknown.

- Citation: Hano H, Takagi I, Nagatsuma K, Lu T, Meng C, Chiba S. An autopsy case showing massive fibrinoid necrosis of the portal tracts of the liver with cholangiographic findings similar to those of primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(4): 639-642

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i4/639.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i4.639

We herein present an unusual autopsy case showing systemic fibrinoid necroses in various organs. The case was strongly suspected clinically of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) based on the cholangiographic findings; however, the autopsy disclosed systemic fibrinoid necroses instead of histological features of PSC. Particularly noteworthy was the presence of fibrinoid necrosis in the portal tracts of the liver caused stenoses of the biliary trees in association with cholestasis. We could not find any similar case reported in the literature. Presently, the etiology remains unknown.

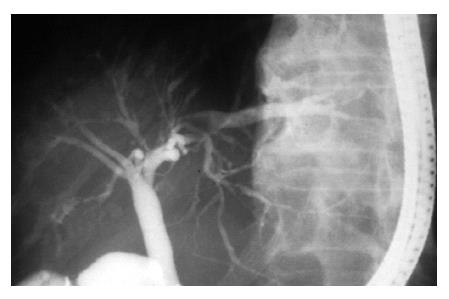

About 10 mo before admission to our hospital, an 81-year-old Japanese man was admitted to a local hospital because of jaundice. Laboratory examinations revealed elevated levels of serum total bilirubin and other serum enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase, leucine aminopeptidase. Serum autoantibodies such as anti nuclear antibody, anti mitochondrial antibody and anti smooth muscle antibody were negative. Endoscopical retrograde cholangiogram showed characteristic irregularity and beading of the intrahepatic biliary tree (Figure 1). No extrahepatic involvement was found. The patient was strongly suspected clinically of PSC. The pathologic diagnosis of the liver biopsy specimen was liver damage with cholestasis. Concentric fibrosis around the bile ducts suggesting PSC was not found. The patient was transferred to our hospital 18 d before death because of aggravation of jaundice, anorexia and easy fatigability. Chronological laboratory data is shown in Table 1. Serum fibrinogen was within normal lower limit. Plasminogen and D-dimer in serum were not examined. Serologic markers for hepatits B and C viral hepatitis were negative. These findings indicated that the liver cell damage rapidly worsened with aggravation of cholestasis, especially in end stage. Despite symptomatic and supportive treatment, the jaundice became progressively worse, and ascites and hepatic encephalopathy developed. The patient eventually died of hepatic failure.

| d 1 | d 38 | d 48 | d 54 | |||||||

| Peripheral blood | Serological tests | |||||||||

| WBC | /μL | (4500-8500) | 8400 | 8800 | 9200 | 16900 | IgG | mg/dL | (800-1800) | 1629 |

| Hemoglobin | g/dL | (13.5-16.5) | 12.1 | 12.9 | 11.5 | 11.4 | IgA | mg/dL | (130-290) | 182 |

| Platelet | × 104/μL | (15.0-35.0) | 26.8 | 26.6 | 20.8 | 18.6 | IgM | mg/dL | (100-180) | 68 |

| C3 | mg/dL | (70-100) | 99 | |||||||

| Coagulation tests | C4 | mg/dL | (11-44) | 46.5 | ||||||

| Prothrombin time | % | (> 70%) | 55 | 37 | 52 | 26 | CH50 | U/mL | (28-45) | 44.6 |

| Hepaplastin test | % | (> 70%) | 90 | 44 | 57 | 38 | Serum-Cu | μg/dL | (78-131) | 247 |

| Fibrinogen | mg/dL | (150-400) | 158 | 176 | 160 | |||||

| Viral markers | ||||||||||

| Blood chemistry | HBsAg | (-) | ||||||||

| AST | IU/L | (10-30) | 185 | 134 | 98 | 422 | HCVAb | (-) | ||

| ALT | IU/L | (6-40) | 126 | 91 | 59 | 174 | ||||

| LDH | IU/L | (160-325) | 450 | 646 | 439 | 812 | Auto antibodies | |||

| ALP | IU/L | (120-400) | 1359 | 834 | 692 | 556 | Anti nucleic antibody | (-) | ||

| LAP | IU/L | (105-235) | 528 | 472 | 425 | LE test | (-) | |||

| γ-GTP | IU/L | (4-70) | 296 | 151 | 119 | 73 | Anti DNA antibody | (-) | ||

| T-Bil | mg/dL | (0.1-0.8) | 10.7 | 15.8 | 16.2 | 18.5 | Anti SMA antibody | (-) | ||

| D-Bil | mg/dL | (0-0.3) | 5 | 9.1 | 10.9 | Anti mitochondrion antibody | (-) | |||

| TP | g/dL | (6.7-8.3) | 6.4 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 4.9 | ||||

| Alb | g/dL | (3.5-5.2) | 3.3 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.6 | Tumor markers | |||

| TC | mg/dL | (120-220) | 260 | 319 | 193 | 158 | AFP | ng/mL | (1-15) | 2 |

| BUN | mg/dL | (8-20) | 32 | 68 | 150 | CEA | ng/mL | (5.8↓) | 6.1 | |

| Cr | mg/dL | (0.5-1.1) | 1.2 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 7.7 | CA19-9 | U/mL | (37↓) | 2470 |

| Serological test | mg/dL | |||||||||

| CRP | (0-0.5) | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 8.8 |

An autopsy was performed about two hours after his death. The diagnoses at autopsy except for systemic fibrinoid necrosis were cholestatic liver damage, acute renal swelling, acute pancreatitis, mild cardiac hypertrophy (350 g) and latent adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Pathologic findings concerning fibrinoid necrosis are described as follows.

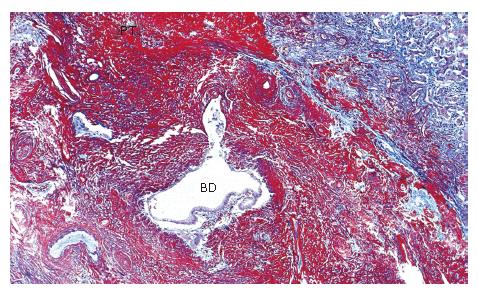

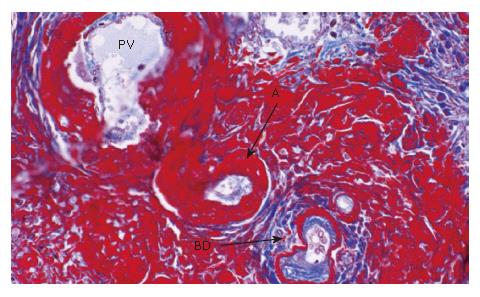

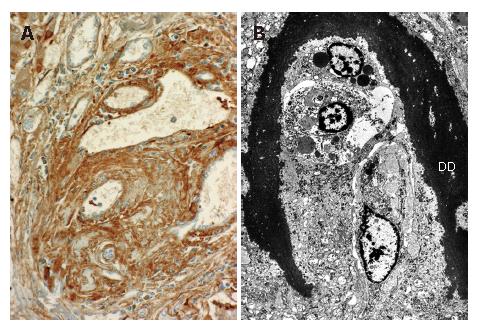

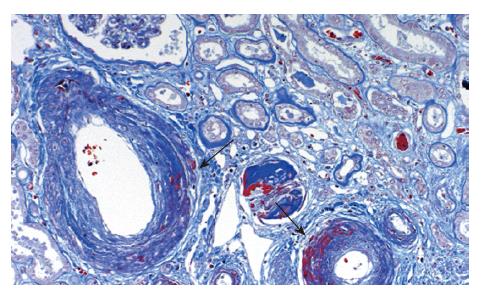

The liver (1380 g) showed a deeply yellow-brown cut-surface due to cholestasis with scattered simple small cysts. Gross examination could not detect remarkable changes of the common bile duct and bilateral hepatic ducts. Microscopically the most striking feature was a massive deposition of homogeneous material stained scarlet with Masson's trichrome in the portal tracts (Figure 2). Careful examinations disclosed that the material was deposited in the walls of arteries and portal veins as well as in the connective tissue (Figure 3). In the bile ducts the deposits circumscribed the lumen leaving the epithelial lining intact and caused marked stenosis. The area of the involved vessels and ducts extended from the distal interlobular portion to the proximal septal portion (Figures 2 and 3). The material was stained violet with PTAH and immunohistochemically was positive for fibrinogen and negative for immunoglobulins such as IgG, IgM, and IgA, C3 and C1q (Figure 4A). Electron microscopic findings of the liver were electron dense materials deposited in the involved tissue (Figure 4B). The results of these stainings and electronmicrogram suggested that the lesion with homogeneous material deposition was fibrinoid necrosis. In addition, the portal tracts were enlarged and infiltrated with lymphocytes and plasma cells with an occasional intermingling of polymorphonuclear cells, ductular proliferation and fibrosis. The histologic features were biliary interface activity, resulting from cholestasis. However, it was noted that the lesion with fibrinoid necrosis was scarcely accompanied by inflammatory reactions. Cholestasis also caused conspicuous paren-chymal damage including feathery degeneration or necrosis. Although the liver was extensively examined histologically, there were no detectable features of PSC.

The kidney (250 g, respectively) showed marked swelling. Histologically fresh fibrinoid necrosis was found in various degrees mainly in the wall of the interlobular arteries (Figure 5). However, it was not accompanied by any inflammatory reaction. Elastica-Van Gieson stain also demonstrated the destructive changes of the arterial walls suggestive of old vascular lesions. Occasionally, focal fibrinoid necrosis involved tubules and connective tissue.

Intensive fibrinoid necrosis was noticed in lymph nodes and the spleen. Old vascular lesions were also found frequently in the spleen. The pancreas, lung and pleura showed scattered foci of fresh fibrinoid change.

On re-examination of the liver biopsy specimen, the same fibrinoid necrosis as observed on autopsy materials was seen in the portal tracts.

The case reported here is characterized with unusual systemic fibrinoid necroses in the walls of blood vessels and connective tissue in various organs, especially in the liver. It is clear that massive fibrinoid material around the bile ducts compressed the lumen and caused various degrees of stenoses. It was considered that such stenosis of the bile ducts resulted in the findings similar to those of PSC on the cholangiogram[1,2]. Obstructive jaundice over time aggravated and severely damaged the liver parenchyma. This was considered to reflect the progressive deposition of fibrinoid material in the portal tracts.

Klemperer proposed the term, collagen diseases, to describe systemic connective tissue disorders that are characterized histologically by fibrinoid necrosis of the connective tissue[3,4]. Thereafter many studies clarified that fibrinoid material is composed mainly of fibrins, while other minor components are immunoglobulins. Although the pathogenesis of fibrinoid necrosis has not yet been fully elucidated, it is assumed to result from the insudation of immunoglobulins into blood vessel walls, leading to activation of the coagulation cascade and deposition of fibrins[5]. Furthermore, fibrinoid necrosis of blood vessels is also known to develop in non-autoimmune diseases like malignant hypertension[6,7]. In our case laboratory findings or symptoms were not suggestive of any autoimmune disease or malignant hypertension. The liver pathology was also quite different from that of reported cases with collagen diseases[8-10]. On a search of the literature using key words such as fibrinoid necrosis, vasculitis, we could not find any case similar to ours.

It is well known that the main cholangiographic features of PSC are a beaded appearance, very short strictures, and diverticulum-like outpourchings[11]. Cholangiographic differential diagnosis of PSC involves cholangiocarcinoma, cirrhosis, acute cholangitis, and advanced primary biliary cirrhosis in general[12]. In addition, it might be necessary, in diagnosing PSC, to keep in mind that the lesions severely involving the portal tracts like our case also cause severe damage, besides stenosis of the biliary tracts.

| 1. | Elias E, Summerfield JA, Dick R, Sherlock S. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the diagnosis of jaundice associated with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1974;67:907-911. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lindor KD, Larusso NF. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Schiff's Diseases of the liver 9th ed. Philadelphia: Liptoncott Williams & Wilkins 2003; 673-684. |

| 3. | Klemperer P, Pollack AD, Baehr G. Landmark article May 23, 1942: Diffuse collagen disease. Acute disseminated lupus erythematosus and diffuse scleroderma. By Paul Klemperer, Abou D. Pollack and George Baehr. JAMA. 1984;251:1593-1594. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Klemperer P. The concept of collagen diseases. Am J Pathol. 1950;26:505-519. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Moor S, Jennette JC, Rosen S. Vascular system. In Damjanov I, Linder J, editors. Anderson's pathology. 10th ed. St. Louis: Mosby 1996; 1397-1445. |

| 6. | Heptinstall RH. Malignant hypertension; a study of fifty-one cases. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1953;65:423-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Olson FG. Hypertension: Essential and secondary forms. Heptinstall's pathology of the kidney. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven 1998; 943-1002. |

| 8. | Matsumoto T, Kobayashi S, Shimizu H, Nakajima M, Watanabe S, Kitami N, Sato N, Abe H, Aoki Y, Hoshi T. The liver in collagen diseases: pathologic study of 160 cases with particular reference to hepatic arteritis, primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis and nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver. Liver. 2000;20:366-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cowan RE, Mallinson CN, Thomas GE, Thomson AD. Polyarteritis nodosa of the liver: a report of two cases. Postgrad Med J. 1977;53:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Burt AD, Portmann BC, MacSween RNM. Liver pathology associated with disases of other organs or systems. In MacSween RNM, Burt AD, Portmann BC, Ishak KG, Scheuer PJ, Anthony PP, editors. Pathology of the liver. 4th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone 2002; 827-883. |

| 11. | LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH, Ludwig J, MacCarty RL. Current concepts. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:899-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gulliver DJ, Baker ME, Putnam W, Baillie J, Rice R, Cotton PB. Bile duct diverticula and webs: nonspecific cholangiographic features of primary sclerosing cholangitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:281-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Ma WH