CASE REPORT

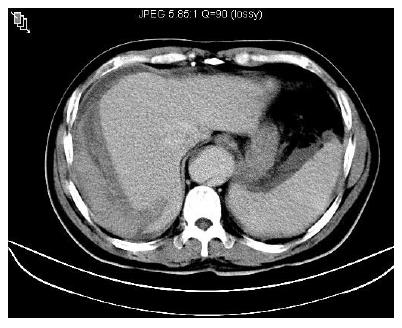

This 43-year-old male taxi driver was diagnosed to have aortic dissection and underwent ascending aortic graft surgery at a medical center 8 years ago, with sequellae of paraplegia and urine incontinence. He had diabetes mellitus and hypertension with regular medication control at our hospital and was found to be seropositive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) during the past 10 years, but he paid no attention to it. Unfortunately, he was admitted because of nausea, vomiting and intermittent right upper abdominal dull pain for one week. The pain could radiate to right upper back and neck, 10-20 min in duration, not related to exercise and relieved spontaneously. He denied any trauma history prior to admission. The pain became more severe with sharp and tearing like features in the midnight prior to admission. On arrival, he was sick, pale and mild short of breath. His blood pressure was 106/66 mmHg, heart rate 102 beats/min, temperature 35.7°C, and respiratory rate 24/min. Tenderness on epigastric and right upper quadrant of abdomen without rebound pain or shift dullness was demonstrated. The liver span was 12 cm in right middle clavicle line. The laboratory tests at emergency room showed 12.9 g/dL hemoglobin, 38.9% hematocrit, 23.8 × 109/L leukocytes, 80 × 109/L platelets, 38 U/L (normal < 34 U/L) aspartate transaminase, 59 U/L (normal < 36 U/L) alanine transaminase, 1.2 mg/dL (normal < 1.3 mg/dL) total bilirubin, 85 U/L (normal 28-94 U/L) alkaline phosphatase, 147 U/L (normal < 26 U/L) γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, 13.3 s (control: 10.8 s) prothrombin time, 2.5 g/dL albumin, 83 U/L (normal < 137 U/L) amylase, 230 U/L (normal < 190 U/L) lipase, 17.9 mg/dL blood urea nitrogen, 2.4 mg/dL creatinine, and 5 ng/mL α-fetoprotein by radioimmunoassay. Unfortunately, fever, chills and hypotension occurred 12 h after admission. His blood pressure dropped to 64/43 mmHg, heart rate was 120 beats/min, respiratory rate was 25/min and central venous pressure was 4 cm H2O. Follow-up hemoglobin fell to 5.8 g/dL, and hematocrit to 18%. HBsAg and antibody to hepatitis delta virus were positive by radioimmunoassay (Ausria II, and Anti-Delta, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA). Antibody to hepatitis C virus by the third generation enzyme immunoassay kit (AxSYM® HCV. Version 3.0 Abbott Lab) was negative. Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed intra-abdominal fluid collection and a 15 cm right subcapsular hematoma over a non-cirrhotic liver. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a right subcapsular hematoma and a ruptured at the right posterior-superior segment of liver (Figure 1) besides a type B aortic dissecting aneurysm. No hepatic aneurysmal lesions were detected in abdominal CT or MRI studies. Coronary arteriography revealed coronary arterial disease. Aortogram revealed chronic complex aortic dissection without rupture. Selective catheterization of the bleeding branch of the hepatic artery was unsuccessful due to tortuous vessels. US guided paracentesis from the right subcapsular hematoma revealed fresh blood with clotting immediately. The patients’ general conditions, including hemogram, body temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate and blood pressure gradually improved after blood transfusion and intravenous fluid resuscitation. He was discharged 13 d after symptoms subsided, and followed up at our outpatient clinic regularly. Follow-up CT 5 mo later showed a 3.5 cm low density liver mass over the right posterior-superior segment (Figure 2). Biopsy of the mass showed only hematoma component without malignancy. The pathology of liver rather than the mass showed chronic persistent hepatitis with the histological activity index (necro-inflammatory score 3 and fibrosis score 0). Liver biochemical tests and alpha-fetoprotein value were normal. The liver hematoma became smaller (1 cm) one year later by CT study. Now, he enjoys his life 4 years after initial diagnosis and no hepatic lesion was detected during the subsequent follow-up.

Figure 1 Abdominal CT on admission showing a subcapular hematoma and a ruptured cleft at the right posterior-superior segment of liver.

Figure 2 Follow-up CT 5 mo later showing the decreased size of subcapsular hematoma (3.

5 cm).

DISCUSSION

Hepatic rupture is mostly caused by trauma. Clinical conditions inducing hepatomegaly, for example, amyloidosis, malaria, venous stasis and enlarged liver tumors, predispose to traumatic rupture[2]. Atraumatic liver rupture is a rare condition with serious consequences, if not recognized and treated in time. Strictly speaking, it is pathologic if the patient has an underlying disease. Otherwise, it is spontaneous[3]. However, in the literature regardless of underlying disease, atraumatic liver rupture is synonymous with spontaneous liver rupture. The clinical manifestations of atramatic acute hemoperitoneum, right subcapsular hematoma of liver, and evidence of chronic hepatitis without HCC in the present case strongly suggest that he was a victim of spontaneous liver rupture. Certainly, it is very difficult to distinguish between atraumatic spontaneous rupture and rupture following trivial trauma.

HCC rupture is the most frequently reported cause of spontaneous liver rupture[4,5]. From a review of 70 Chinese patients with spontaneous liver rupture reported by Chen et al[5], the major cause is HCC (85.7%) followed by adenoma (5.7%), cirrhosis (4.3%), hemangioma (2.9%), and metastatic liver tumor (2.9%)[5]. Review of the literature disclosed that other conditions associated with spontaneous liver rupture include other benign and malignant liver tumors, pregnancy related disorders (acute fatty liver, preeclampsia and eclampsia of pregnancy[6,7], amyloidosis[2], peliosis hepatitis, autoimmune diseases (systemic lupus erythematous, rheumatoid arthritis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa)[8,9], anticoagulant therapy, liver transplantation[1], aortic aneurysm surgery[10], peritoneal hemodialysis[11], and perforated gastric ulcer[12].

Atraumatic liver rupture is usually preceded by subcapsular hematoma[6]. Epigastric or right upper quadrant abdominal pain is the most common symptom of subcapsular hepatic hemorrhage. Patients may suffer from pain for several days or weeks before rupture of the capsule. Physical examination usually reveals hepatomegaly, right upper quadrant tenderness. Abdominal distention, peritoneal signs and shock are usually present when rupture Occurs[2,4]. The diagnosis of spontaneous liver rupture is often confirmed by imaging studies in a stable patient because initial clinical suspicion is low. In a hemodynamically unstable patient, an abdominal US in an emergency room may demonstrate ascites in the peritoneal cavity and a mass lesion in liver. Hepatic subcapsular hematoma can be diagnosed by abdominal US, MRI or nuclear scan, but abdominal CT is the most sensitive and specific imaging examination[13]. Abdominal US can usually distinguish liver rupture from biliary tract disease, and can diagnose a subcapsular hematoma. However, it is difficult to distinguish hepatic hematoma from liver abscess by US only and these two entities should be differentiated by other methods such as abdominal CT or paracentesis. Paracentesis can also document blood in the peritoneal cavity when rupture occurs[6]. Control of bleeding is the crucial management in patients with spontaneous liver rupture. Treatment options include conservative treatment, transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization, or surgery. In patients with spontaneous HCC rupture, surgery can achieve hemostasis in more than 95% of cases[5] and selective surgical intervention is better than an aggressive surgical approach[14]. Transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization gives usually only temporary effect with surgical intervention in ruptured amyloid livers[2]. However, the mortality is the highest with surgery and the lowest with transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization of a bleeding hepatic artery when rupture occurs in pregnant women[7]. These reports suggest that the best choice of treatment depends on the underlying etiology and individualized patient’s condition.

The exact mechanism of spontaneous liver rupture is controversial. Spontaneous liver rupture in amyloidosis has been thought to be due to liver enlargement, rigidity of hepatic parenchyma, and vascular fragility from amyloid involvement[15]. Spontaneous liver rupture in pregnancy may be due to hepatic infarction resulting from gross ischemia and obstruction to the sinusoidal blood flow by deposited fibrin and relative hypovolemia[6]. In HCC or other malignant liver tumors, the pathogenesis of spontaneous liver rupture may be attributed to the overlying normal liver parenchyma splitting from the expanding tumor growth, a tear in tumor surface, rupture of parasitic feeding artery, or hemorrhage caused by tumor necrosis locating near the liver surface[16]. Venous congestion secondary to obstruction of hepatic venous outflow of the tumor by thrombi, together with rich and fragile arterial supply may contribute to the rupture of HCC[17]. We have previously reported a spontaneous spleen rupture patient with hepatitis B virus related cirrhosis[18], and two cases of spontaneous liver rupture in cirrhosis were also mentioned by Chen et al[5]. Portal hypertension may play an important role in these 3 cases. To the best of our knowledge, the present case is the first case of spontaneous liver rupture in a non-cirrhotic liver disease. Liver biopsy of this patient showed fibrosis score 0 by histological activity index scoring system[19], excluding the possibility of liver cirrhosis, even though a possible sample bias was present. Li et al[9] speculated that spontaneous liver rupture in polyarteritis nodosa is due to massive bleeding from an aneurysmal intrahepatic artery. The present case suffered from chronic aortic dissecting aneurysm and perhaps concomitant vascular lesions, such as a small intrahepatic aneurysm along with hepatitis. However, abdominal CT and MRI revealed no hepatic aneurysmal lesions. Detailed history and careful physical examination excluded traumatic injury. The definite cause of liver rupture in our case remains unclear.

In summary, spontaneous liver rupture is a medical emergency. This case report suggests that the possibility of spontaneous liver rupture should be considered if a patient presents with acute hemoperitoneum. It is a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for the clinician because of its rarity and potential lethal entity. The optimal choice of treatment depends on the underlying etiology. Understanding the common causes of spontaneous liver rupture helps the clinician to make a correct judgment and management in time.