INTRODUCTION

An abnormally positioned liver is a rare developmental error, mostly found incidentally. It is classified into (1) ectopic liver, which is not connected to the mother liver and usually attached to the gallbladder or intra-abdominal ligaments, (2) microscopic ectopic liver found occasionally in the gallbladder wall, (3) a large accessory liver lobe attached to the mother liver by a stalk (pedunculated liver), and (4) a small accessory liver lobe attached to the mother liver[1]. In many cases, distinct separation of ectopic liver and accessory liver is difficult. The incidence of ectopic liver has been reported to be 0.24%-0.47%[2,3]. Ectopic liver is usually asymptomatic, but occasionally causes unexpected problems such as intra-abdominal bleeding and hepatocarcinogenesis[4,5]. Recently, we encountered a patient with a pancreatic tail tumor that was histologically diagnosed as ectopic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Herein we describe the case with a review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

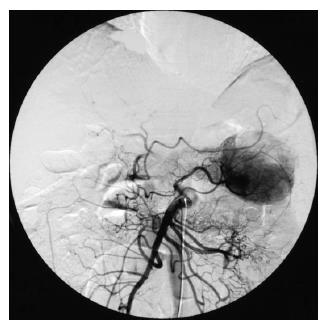

A 56-year-old man had been followed up at a nearby hospital for diabetes mellitus. In February 2004, he underwent an abdominal ultrasound examination during a routine check-up, which demonstrated a 65-mm tumor in the pancreatic tail. He was therefore, referred to our department for further investigation. Physical examination showed no abnormal findings. Blood chemistry on admission was all normal except for a high HbA1c level by 6.8%. All serum markers for hepatitis B or C virus were negative. Tumor marker levels in the serum were within the normal range: CEA 1.7 ng/mL (normal range: < 6), CA19-9 30 U/mL (normal range: < 37), DUPAN-2 < 25 U/mL (normal range: < 590), elastase 1180 ng/mL (normal range: < 400), CA-50 7.7 (normal range: < 40) and SPAN-1 15 U/mL (normal range: < 30). Serum AFP and PIVKA-2 levels were not measured. Abdominal ultrasound showed an encapsulated, rather heterogeneous, hypoechoic tumor, 6.5 cm in maximum diameter, with a beak sign (Figure 1). Plain CT showed a tumor with iso-density but partial low density in the pancreatic tail. Helical dynamic CT revealed an irregularly enhanced tumor with pooling of contrast medium in the delayed phase (Figure 2). MRI demonstrated that the tumor had low intensity in T1-phase and irregularly high intensity in T2-phase. Abdominal angiography showed a hypervascular tumor fed by both the splenic artery and dorsal pancreatic artery from the superior mesenteric artery (Figure 3). Pancreatic hormones, including insulin, gastrin and glucagons, were within the normal range. With a tentative diagnosis of non-functional islet-cell tumor, the patient underwent resection of the pancreatic body and tail with splenectomy. At laparotomy, the tumor was confirmed to be located in the pancreatic tail. The contour of the liver and its surface were normal.

Figure 1 Abdominal ultrasound examination, showing an encapsulated, rather heterogeneous, hypoechoic tumor, 6.

5 cm in maximum diameter, with a beak sign.

Figure 2 Helical dynamic CT, revealing an irregularly enhanced tumor with pooling of contrast medium in the delayed phase.

Figure 3 Abdominal angiography.

The tumor was hypervascular, fed by both the splenic artery and dorsal pancreatic artery from the superior mesenteric artery.

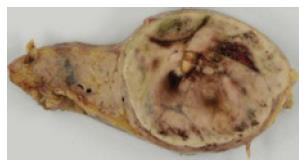

The gross specimen consisted of an elastic, hard and well-demarcated tumor, 6.3 cm × 6.2 cm in size, a spleen, and a partially resected pancreas. The cut surface of the mass was reddish-yellow and showed focal hemorrhage with a necrotic appearance (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Macroscopic findings.

The cut surface of the mass was reddish-yellow, with focal hemorrhage and a necrotic appearance.

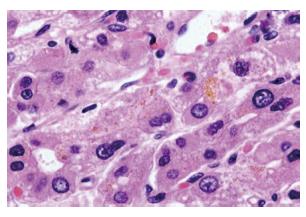

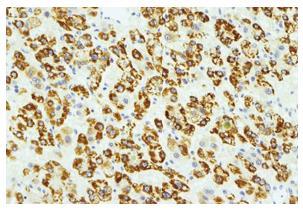

In microscopic examination, the tumor cells grew in trabeculae that were separated by sinusoid-like blood spaces. These tumor cells consisted of polygonal cells with fine granular eosinophilic cytoplasm resembling hepatocytes (Figure 5). Bile production was also observed. These findings supported a diagnosis of moderately differentiated HCC. Many cancer cells were positive for HEPPAR-1 (Figure 6), COX-2, CK18 and CAM5.2, but negative for AFP, MOC-31, MUC1, TTF-1, CK7, CK8, and CK20 in immunostaining. These findings strongly suggested that this tumor was a HCC without an adenocarcinoma component.

Figure 5 Histological findings (HE, x 400).

The tumor cells grew in trabeculae that were separated by sinusoid-like blood spaces. These tumor cells were polygonal with fine granular eosinophic cytoplasm, resembling hepatocytes.

Figure 6 Immunohistochemical staining (HEPPAR-1).

The tumor cells were positive for HEPPAR-1, suggesting that they had the nature of hepatocytes.

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful. He is currently doing well without any signs of recurrence in either the remaining pancreas or the liver three years after surgery.

DISCUSSION

Sites of ectopic liver include the gallbladder, spleen, retroperitoneum, pancreas, adrenal gland, portal vein, diaphragm, thorax, gastric serosa, testis and umbilical vein[6]. Only one case of ectopic liver in the pancreas has been reported previously[7]. Both the dorsal pancreatic bud and the hepatic diverticulum develop from the foregut almost at the same time in the 4th embryonic week[8]. It is suggested that liver tissue can migrate to various organs during embryogenesis[9]. This may explain the occurrence of ectopic liver in the dorsal part of the pancreas.

In ectopic liver, both benign and malignant lesions can develop. Benign lesions may be less frequent and up to now, 10 pedunculated hemangiomas, one adenoma and one focal nodular hyperplasia have been found[10-16]. On the other hand, HCC has been reported to develop in the ectopic liver in 34 cases, including the present one, 26 cases have been reported in Japan[4,5,17-28]. The ectopic HCCs were found in various sites including the chest wall, gastric wall, jejunum and pancreas. The affected patients comprised 27 men and 7 women with a mean age of 62.5 years (range: 34-77 years). When ectopic HCCs were detected, the mother liver showed cirrhosis in 7 patients and chronic hepatitis in 4, while in the remaining 22 patients, the liver was normal or non-cirrhotic. Although information on hepatitis viral status was not available in all cases, anti-HCV antibody was positive in two of 15 patients and hepatitis B surface antigen was positive in two of 25. It is likely that nonviral factors are involved in the carcinogenesis. In order to support a diagnosis of HCC in ectopic liver, non-cancerous liver parenchyma should persist around the HCC. However, non-cancerous liver parenchyma has not been present in most of the cases reported up to now, including the present one, and was presumed to have been completely replaced by the HCC. In one case reported by Arakawa et al[4], a part of the mass contained normal liver tissues with portal triad. It was suggested that ectopic liver may develop HCC much earlier than the mother liver, or that it is more prone to hepatocarcinogenesis. Small volumes of ectopic liver tissues do not have a complete functional architecture, and may be metabolically handicapped, thus facilitating carcinogenesis. The possibility of metastasis to the pancreas was ruled out because there was no HCC in 33 of the 34 patients with a clear description about the condition of the mother liver. In our patient, no HCC has been detected in the mother liver for 3 years since the operation. In 4 (12%) of the 34 patients, ectopic HCC was revealed because of rupture, presenting as a shock condition. The rupture rate for ectopic HCC is similar to that for HCC in the liver[29,30]. When abdominal crisis is encountered, this special condition should be borne in mind. In our patient, the tumor was detected at a routine check-up for diabetes mellitus. CT showed a heterogeneous mass with irregular enhancement, and abdominal angiography demonstrated a hypervascular tumor[24]. From these findings, non-functional islet cell tumor was suspected. Unfortunately, AFP and PIVKA-II were not measured, and a preoperative diagnosis of HCC was not considered. A similar case was described by Cardona et al[28]. In their case, the tumor was also diagnosed as an endocrine tumor and was confirmed to be a HCC by histological examination. In 8 of the 34 reported cases, HCC was suspected according to the diagnostic imaging, and a high level of AFP or biopsy findings helped establish the diagnosis. However, in most cases, HCC was diagnosed based on the postoperative histological examinations.

In addition to the histological findings, immuno-histochemistry is necessary for differentiation between hepatoid carcinoma and an ectopic HCC. Hepatoid carcinoma of the pancreas is a pancreatic acinar neoplasm showing foci of hepatocellular differentiation[31-33]. Venous invasion by tumor cells is a frequent feature of hepatoid adenocarcinoma, and may be associated with poor prognosis. In the present case, adenocarcinoma components were not present and there was no immuno-histochemical evidence of adenocarcinoma. Although non-cancerous liver tissue was not observed, all the findings supported the diagnosis of ectopic HCC.

In seven cases with a clear description about outcome, recurrent lesions developed in the liver, lung or brain, while 13 patients were alive without any signs of recurrence at 27.5 mo after surgery. Surgery, if possible, is the most preferable treatment option.

In summary, we have reported a rare case of ectopic HCC in the pancreas. When a heterogeneously enhanced solid tumor is observed in the abdomen, ectopic HCC should be borne in mind as a rare possibility, and measurement of AFP is recommended.