INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic cholecystitis is an infrequent form of cholecystitis[1,2]. In the clinical practice, eosinophilic cholecystitis is usually unsuspected and is clinically indistinguishable from the predominant form of calculous cholecystitis[2,3]. Although the etiology of eosinophilic cholecystitis is still obscure, the postulated causes include allergies, parasites, hypereosinophilic syndrome, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and local reaction to gallstones[4]. It sometimes shows a marked peripheral blood eosinophilia. Peripheral eosinophilia indicates that eosinophilic cholecystitis is likely to be a manifestation of a systemic hypereosinophilic disorder[4]. A marked peripheral blood eosinophilia is associated with several biological conditions, such as allergy, hypersensitivity diseases, parasitic infections, connective tissue disorders, blood dyscrasias, malignancies, and immunodeficiency status[5,6]. Eosinophilic infiltration can be associated with disorders of the lung, heart, gastrointestinal tract, biliary tract, and gall bladder[6]. Although eosinophilic cholecystitis sometimes accompanies other organ dysfunction, close temporal association with pericarditis has been very rarely reported so far.

Ascariasis, a helminthic infection of man, is the most common parasitic infection of the gastrointestinal tract, but invasion of worms into the gall bladder is rare (2.1% of the hepatobiliary ascariasis in endemic areas)[7,8]. Regarding the imaging modalities available for diagnosis of biliary ascariasis, recent studies have shown that abdominal ultrasonography (US) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) are very useful, sensitive, safe, and non-invasive[8-10]. Herein, we report a case that showed simultaneous onset of acute cholecystitis and pericarditis (diagnosed by abdominal US and MRCP) along with a marked eosinophilia caused by Ascaris lumbricoides infection.

CASE REPORT

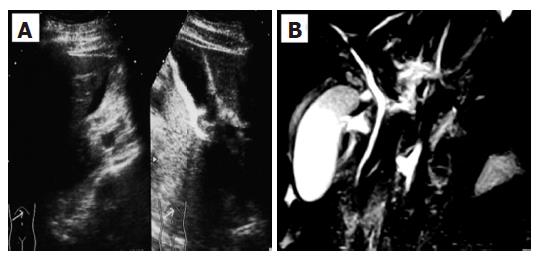

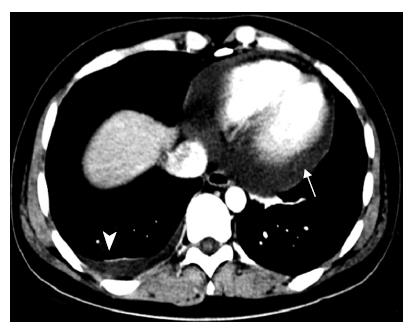

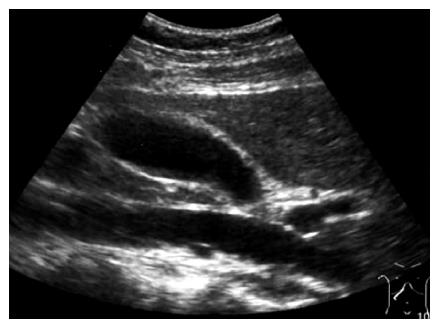

A 28-year-old woman was admitted into our hospital complaining of acute right hypocondrial pain and dyspnea associated with systemic eruption. She did not have specific past medical history including allergic reactions. Physical examination demonstrated a severe right hypocondrial tenderness, high-grade fever, and systemic eruption. The systemic eruption mainly consisted of wheal, and was diagnosed as urticaria. Laboratory examination revealed mild elevation of transaminases, biliary enzymes, and a marked eosinophilia along with elevation of IgE. Abdominal US revealed that a marked gall bladder swelling and wall thickness without stones or debris, indicating an acute cholecystitis (Figure 1A). Subsequently, MRCP was carried out for further confirmation of the US diagnosis. MRCP revealed similar findings as well as a free space around the gall bladder, suggesting exudates associated with severe inflammation (Figure 1B). Furthermore, chest computerized tomography (CT) scanning, in turn, revealed a massive pericardial effusion and moderate right pleural effusion (Figure 2). Echocardiography confirmed a massive pericardial effusion without asynergy or valvular disorder. Although we could not detect any worm lying either in the bile duct or gall bladder, we suspected parasitic infection because of marked eosinophilia and IgE elevation along with systemic urticaria [31% of leukocyte (7500/μL) and 246.6 U/mL, respectively]. Her serum had a high titer of antibody against Ascaris suum and Toxocara canis (pig ascaris and dog ascaris, respectively) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (generously measured by Dr. Hiromatsu; Department of Parasitology, Miyazaki University School of Medicine) (150-fold and 100-fold higher as compared with the control serum, respectively). Treatment with albendazole (600 mg/d) drastically improved all clinical manifestations along with normalization of the imaging findings, eosinophilia, and IgE elevation within a week after the treatment. Abdominal US revealed disappearance of the gall bladder swelling and wall thickness after only four days treatment with albenzasole (Figure 3). The free space around the gall bladder vanished, too. She discharged the hospital four-week after the treatment with albendazole.

Figure 1 A: Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed a marked gall bladder swelling and wall thickness without stones or debris, indicating an acute cholecystitis; B: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed a similar gall bladder thickness as well as free space around the gall bladder, suggesting exudate associated with severe inflammation.

Figure 2 A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showing massive pericardial effusion (arrow) and right pleural effusion (triangle).

Figure 3 After treatment with albendazole, abdominal US revealed disappearance of the gall bladder swelling and wall thickness.

DISCUSSION

Eosinophilic cholecystitis is an infrequent form of cholecystitis that was first described by Albot in 1949[1]. The physical and laboratory findings are not specific. Although the etiology of eosinophilic cholecystitis is still uncertain, the postulated causes include parasites, gallstones, and allergic hypersensitivity response to drugs such as phenytoin, erythromycin, cephalosporin, and herbal medications[4,11]. Eosinophilic cholecystitis may develop with several diseases, such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis, eosinophilic pancreatitis, and idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES)[6,12,13]. In the literature, we found only one report on a case of eosinophilic cholecystitis that developed almost simultaneously with eosinophilic appendicitis and eosinophilic pericarditis[4]. Our case is very rare because of the simultaneous onset of eosinophilic cholecystitis and pericarditis caused by parasite; namely, Ascaris lumbricoides.

Unlike eosinophilic gastritis, most patients with eosinophilic cholecystitis have no history of allergy as in our case[14]. Peripheral hypereosinophilia is not a constant finding, either, although the characteristic histologic feature of eosinophilic cholecystitis is transmural inflammatory infiltration of the gall bladder wall that is composed of more than 90% eosinophils[2]. In the current case, we did not have any histological evidence of eosinophilic cholecystitis since the patient did not undergo cholecystectomy. This is the main negative point of the final diagnosis of eosinophilic cholecystitis in our case. However, the patient exerted a marked peripheral eosinophilia and elevation of IgE along with confirmation of acute cholecystitis by several imaging modalities. It has been reported that a marked peripheral eosinophilia usually correlates with eosinophilic infiltration in the gall bladder wall[2,4,14], indicating that, at least, there was some infiltration of eosinophils in the gall bladder in our case. After treatment with albendazole, eosinophilia, IgE elevation, and all clinical manifestations drastically improved along with normalization of the imaging features.

Ascariasis is the most common helminthic infection, which occurs commonly in the tropical and/or developing countries, partly due to the poor sanitary and hygienic conditions that help maintain the infection cycles[15]. In addition to these areas, ascaris infection is sometimes observed even in the industrial countries because raw food may be contaminated with worms. From the duodenum, the worms can enter the biliary tract resulting in right hypocondrial pain. Our patient had eaten fresh vegetables on the day before admission and had severe right hypocondrial pain at admission.

Abdominal US is now recognized as a very useful modality for diagnosis of biliary ascariasis[10]. It can detect adult worms in the biliary tract as a longitudinal structure with inner parallel linear bands and undulating movements inside the gall bladder[8]. MRCP has been the latest innovation for examination of the biliary tract. MRCP has the advantage of providing three-dimensional images of the biliary tract without the risks of contrast allergy and invasiveness. On MRCP imaging, adult worms may be detected with round shape lying obliquely in the bile duct[9]. These modalities sometimes can monitor the slow movement of the worms inside the bile duct and gall bladder. Since we could not detect the worm with either modality, these movements could not be followed up in our case. Probably, only the larva of Ascaris lumbricoides migrated into the biliary tract and gall bladder, which were too small to be detected with these modalities in the current case.

In conclusion, herein we reported a rare case of simultaneous onset of acute cholecystitis and pericarditis associated with a marked eosinophilia caused by Ascaris lumbricoides. Since the physical findings of eosinophilic cholecystitis are indistinguishable from manifestations of the common acute cholecystitis, physicians should be aware of biliary ascariasis in patients with manifestations of acute cholecystitis, and should search for worms by abdominal US and MRCP.