Published online Jul 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3758

Revised: April 10, 2007

Accepted: April 16, 2007

Published online: July 21, 2007

We report a case of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) with benign lyphadenopathy which was diagnosed with endosonography guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA). A 65-year-old woman was admitted to Jikei University Hospital with severe jaundice. Although endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and liver biopsy revealed the findings consistent with PSC, abdominal computed tomography revealed numerous large perihepatic lymph nodes with a maximum diameter of more than 3 cm. Therefore, EUS-FNA was done in order to exclude malignant lymphadenopathy, and adequate specimens obtained by EUS-FNA showed reactive hyperplasia of lymphnode. The patients were scheduled to undergo liver transplantation.

- Citation: Tsukinaga S, Imazu H, Uchiyama Y, Kakutani H, Kuramoti A, Kato M, Kanazawa K, Kobayashi T, Searashi Y, Tajiri H. Diagnostic approach using endosonography guided fine needle aspiration for lymphadenopathy in primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(27): 3758-3759

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i27/3758.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3758

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a disease of unknown etiology that is associated with inflammatory bowel disease and with an increased risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma[1]. Although the course of PSC varies from one patient to another, the disease is generally progressive and usually leads to the development of liver cirrhosis. Advanced PSC is therefore considered to be an indication for liver transplantation. It has been reported that perihepatic lymphadenopathy occurs in approximately 70% of patients with PSC[2,3]. Although most of such lymphadenopathy is benign, it can also be caused by concomitant cholangiocarcinoma[2]. It is very important to detect malignant lymphadenopathy in PSC patients, because the existence of a malignant tumor, especially cholangiocarcinoma, has an adverse effect on survival after liver transplantation[1,2].

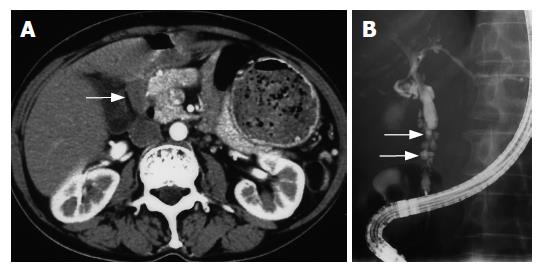

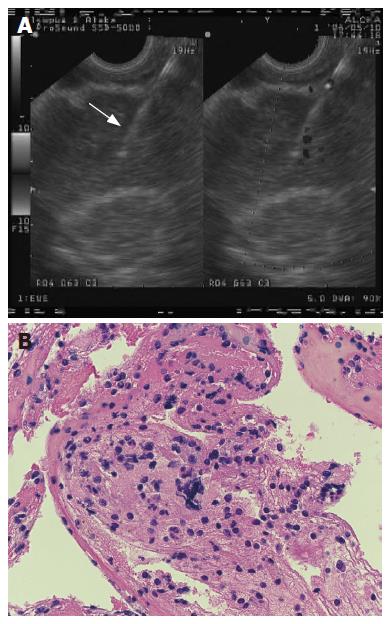

A 65-year-old woman was admitted to Jikei University Hospital (Tokyo, Japan) with severe jaundice. Laboratory tests revealed a serum albumin level of 2.0 mg/dL, while aspartate aminotransferase was 124 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase was 76 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase was 1373 IU/L, and CA19-9 was 114 U/L. Her total bilirubin level was 9.7 mg/dL, with a direct bilirubin level of 5.8 mg/dL. Abdominal computed tomography revealed numerous large perihepatic lymph nodes with a maximum diameter of more than 3 cm, although no mass lesion was seen (Figure 1A). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) showed a bile duct stricture associated with a diverticulum-like out pouching (Figure 1B), and brushing cytology was Class II. A diagnosis of PSC was made on the basis of liver biopsy and typical ERC findings, but the possibility of concomitant cholangiocarcinoma was also considered because of her lymphadenopathy and severe bile duct stricture. Therefore, EUS-FNA was conducted to obtain biopsy specimens of the enlarged lymph nodes and to investigate the presence of concomitant cholangiocarcinoma. A curvilinear echoendoscope (GF UCT240-AL5, Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) was advanced into the duodenum, and biopsy of enlarged lymph nodes was done through the duodenal wall using a 22-gauge echo-tipped needle (Willson-Cook, Winston) (Figure 2A). Adequate biopsy specimens were obtained for histological examination, which revealed reactive hyperplasia of the enlarged lymph nodes with infiltration of lymphocytes (Figure 2B). Since concomitant cholangiocarcinoma was excluded by this histological finding and brushing cytology under ERC, she was scheduled to undergo liver transplantation. Although she is waiting for liver transplantation for six months at present, malignant lesion including cholangiocarcinoma and additional lymphadenopathy has never been seen.

EUS-FNA has emerged as an effective method for obtaining tissue samples from the perigastric and periduodenal organs, such as the pancreas, and for the investigation of peri-intestinal and celiac lymphadenopathy[4]. Although a high sensitivity and specificity of EUS-FNA without any severe complications have been shown for the diagnosis of various diseases[4], there have been few information about its use for lymphadenopathy in patients with PSC. In our present patient with PSC, EUS-FNA was both convenient and effective for making a diagnosis of perihepatic lymphadenopathy. We recommend this diagnostic approach to lymphadenopathy in patients with PSC, especially prior to liver transplantation, to exclude concomitant malignancy. However, further studies will be needed to confirm the clinical value of EUS-FNA for patients with PSC.

| 1. | Burak K, Angulo P, Pasha TM, Egan K, Petz J, Lindor KD. Incidence and risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:523-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Johnson KJ, Olliff JF, Olliff SP. The presence and significance of lymphadenopathy detected by CT in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Br J Radiol. 1998;71:1279-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hirche TO, Russler J, Braden B, Schuessler G, Zeuzem S, Wehrmann T, Seifert H, Dietrich CF. Sonographic detection of perihepatic lymphadenopathy is an indicator for primary sclerosing cholangitis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:586-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Erickson RA. EUS-guided FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:267-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Lu W