INTRODUCTION

Basaloid-squamous cell carcinoma (BSC) is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which mostly arises in the aerodigestive tracts in the region of hypopharynx, oral cavity, and larynx[1-4]. Primary BSC of esophagus is an extremely rare tumor[5] and only about 0.1% out of esophageal carcinoma cases have been diagnosed as primary BSCs[6,7]. Reportedly BSC in the upper aerodigestive tract exhibited a more aggressive clinical course and worse outcomes than SCC[2]. This is because of its biologically malignant features characterized by a poor degree of differentiation, high proliferation activity, and high incidence of distant metastasis[3,4,8].

Localized esophageal BSCs without direct invasion to the surrounding organs or distant metastasis (stageIand II) had been treated by surgical operation, and the median survival time was similar to that of esophageal SCC[9]. On the other hand, for patients with distant metastasis or inoperative recurrence after surgical resection, systemic chemotherapy had been performed but the effectiveness of the therapy was not assured. Although several chemotherapeutic regimens have been conducted for patients with inoperable recurrent or metastatic BSCs[10,11], the standard chemotherapeutic regimen has not been established because of a limited number of those with the disease.

Here we report a case of recurrent esophageal BSC with liver, spleen, and lymph node metastases, which was successfully treated with a combination of 5-FU and CDDP. This regimen allowed partial response of the disease lasting for 6 mo.

CASE REPORT

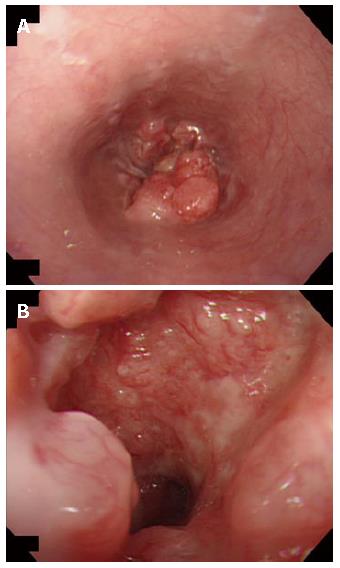

A 57-year-old woman suffering from dysphagia for 3 mo. was diagnosed with an irregular shadow of the esophagus by a barium meal examination in December 2002. Endoscopic examination of the esophagus revealed an elevated lesion with ulceration at the lower esophagus and esophago-gastric junction (Figure 1A and B). Histological diagnosis of the biopsy specimen was moderately to poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed thickening of the esophageal wall, but there was no evidence of either invasion to the adjacent structure or metastasis to distant organs. She underwent curative esophagectomy with lymph node dissection under the thoracoscope in February 2003, and the postoperative course was uneventful.

Figure 1 A: Preoperative endoscopy showing a protruding tumor of the lower esophagus; B: Close endoscopic view of the esophageal tumor with ulceration.

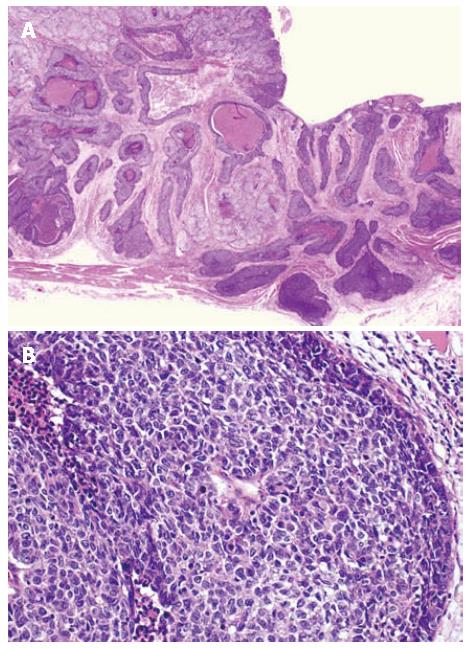

Macroscopically, the resected specimen showed an elevated lesion with ulceration, measuring 6.0 cm × 4.0 cm, located in the lower esophagus (Figure 2). Microscopically, the carcinoma invaded the whole layers of the esophagus with venous invasion but not lymphatic invasion. The proximal and distal margins were free of the carcinoma. The carcinoma was composed of solid nests of basaloid cells in a lobular configuration with peripheral palisading. The carcinoma cells are characterized by having scant cytoplasm, round to oval nuclei and a high nuclear cytoplasmic ratio. Foci of a squamous cell carcinoma in situ, central necrosis (comedo-type necrosis) and deposition of basement membrane-like material were also seen (Figure 3A and B). Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for a high molecular weight cytokeratin (CK14) and bcl-2 protein, but were negative for a low molecular weight cytokeratin (CAM5.2) and neuroendocrine markers (chromogranin A and CD56). The histological feature was compatible with BSC. All the regional lymph nodes were free of the carcinoma.

Figure 2 The resected specimen of esophagus having a protruding tumor with ulceration.

Figure 3 Histological finding of basaloid-squamous carcinomas (HE).

A: Lower magnification; B: Higher magnification.

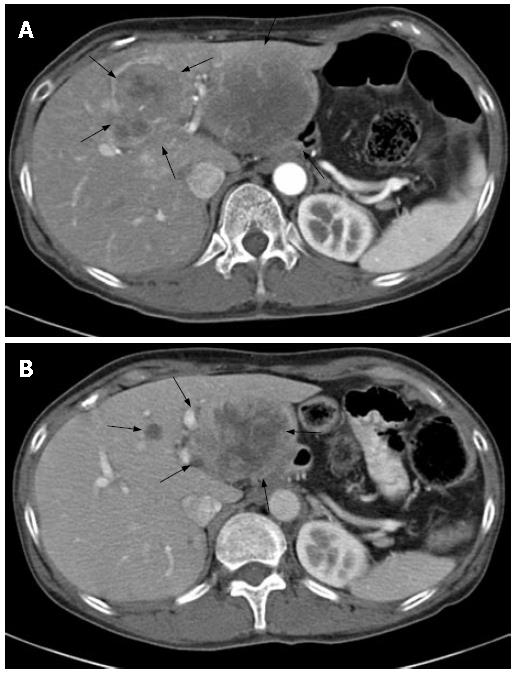

Five months post operation, the patient noticed a mass in the upper abdomen. A CT scan revealed multiple masses of the liver (Figure 4A), a single mass of the spleen, and a right paraclavicular lymph node swelling. Liver biopsy revealed a metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. The blood count and serum biochemical analysis showed no abnormalities except for slight hypochromic anemia and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 752 U/L (normal range: 119-229 U/L). The tumor markers including Squamous cell carcinoma related antigen (SCC), Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA) were within normal limits. The patient was then treated with systemic chemotherapy upon obtaining her agreement. The chemotherapy regimen consisted of continuous infusion of 800 mg/d of 5-FU and 3 h infusion of 20 mg/d of CDDP for 5 consecutive days, every 4 wk. After 2 courses of chemotherapy, the metastatic tumor of the spleen and the paraclavicular lymph node swelling disappeared and liver masses decreased in size. Consequently, the tumor regression rate was 55% evaluated by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), being considered as partial response (Figure 4B). Grade 2 thrombocytopenia was only at a hematological toxicity during these courses. The disappearance of the metastatic tumor of the spleen and the paraclavicular lymph node swelling was observed on the following CT. The tumor regression continued for 6 courses, with re-growth of the tumor afterwards. Therefore the second line chemotherapy using CPT-11 80 mg/d and CDDP 30 mg/d was initiated on d 1 and d 18. However, increased size of liver masses and appearance of new lesion in the liver and spleen were detected after the first course. The patient was further treated by docetaxel 100 mg/d and vinorelbine 26 mg/d on d 1, every 3 wk. Because of grade 4 myelosuppression after the first course, both docetaxel and vinorelbine were reduced by 20% from the second course. No serious adverse events were observed except for grade 3 myelosuppression after the second course. Disease remained stable for 4 courses without tumor progression. Thereafter, liver tumors increased in size and malignant peritonitis appeared invading the transversal colon. The patient died of these tumors in August 2004.

Figure 4 Abdominal computed tomography (CT) images.

A: CT image on admission revealing liver metastasis; B: CT image after 3 courses of 5FU/CDDP chemotherapy showing tumor regression (55%).

DISCUSSION

Since the first description of BSC by Wain et al[2] in 1986, BSCs has been thought to be rare malignant tumor and comprise approximately 0.1% of esophageal carcinoma in a Japanese study[6]. On the other hand, Sarbia et al[12] showed that 11.3% of the esophageal carcinoma were BSCs. This discrepancy of the incidence of BSC between races could be explained by difficulty of differential diagnosis by histological properties. Establishing a diagnosis of BSCs by preoperative biopsy was reported to be so difficult that only 10% of BSC cases, which were histologically confirmed by resected specimen, were correctly diagnosed and another 55% were misdiagnosed as SCC[13]. Although the present case was diagnosed as SCC before operation, resected specimens revealed the existence of solid nests of basaloid cells accompanied by well differentiated SCC and finally diagnosed as BSC. Interestingly, liver biopsy specimens after recurrence of the disease only possessed the features of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. This is probably because a limited amount of specimens were obtained for histological diagnosis or because metastatic liver tumors may derive from more malignant constitute of heterogeneous primary esophageal tumors.

BSC has been reported to be biologically malignant because of the poorly differentiated, highly proliferative activity, and high expression of angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor. Furthermore, it has been reported that the expression of Bcl-2 protein, which plays a role in the suppression of apoptosis, is weak in poorly differentiated SCC, but strong in BSC[14]. In addition to Bcl-2, high expression of c-myc, epidermal growth factor receptor, and pyrimidine nucleoside phosphorylase (PyNPase) may also be associated with the poor prognosis of the BSC[7,15,16].

In the chemotherapy for the most cases of BSC, 5FU/CDDP was employed either in neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings or for the advanced cases. Only Tukayama et al[7] reported neoadjuvant chemotherapy with 5FU/CDDP/VDS. Although, taxan[17] and nedaplatin[18] were often used for SCC, there was no report that these anticancer agents were used for BSC.

The synergistic effect of cytotoxicity in tumor cells has been well recognized in 5-FU and CDDP combination. 5-FU has been shown to augment the cytotoxicity of CDDP or even circumvent CDDP resistance by inhibiting the repair of platinum-DNA interstrand crosslinks as well as by reducing the content of glutathione, a detoxifying compound[19-21]. Combined chemotherapy using CDDP and 5-FU has been well established for advanced esophageal SCC, with response rates being approximately 50%-60%[22]. However the efficacy of this chemotherapy regimen for esophageal BSC has not yet been determined. Koide et al[10] reported that preoperative chemotherapy using 5-FU and CDDP showed tumor regression rate by 61.1%-84.6% against BSC. Tsuchiya et al[11] reported that this combination exhibited tumor regression in neoadjuvant settings and was also effective in the recurrent disease of BSC. While accumulating evidences revealed that postoperative chemotherapy improves disease free survival of patients with esophageal SCC[23,24], we do not have enough data yet for concluding that postoperative chemotherapy is beneficial for BSC. However, concerning the poor outcome after surgery because of its clinicopathologically aggressive behavior in several reports, it may be possible that postoperative chemotherapy for BSC would become a beneficial treatment. An accumulation of cases is required to establish the role of this combination in the therapy of esophageal BSC.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Li M E- Editor Wang HF