Published online Jun 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i24.3288

Revised: March 1, 2007

Accepted: March 7, 2007

Published online: June 28, 2007

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a relapsing and remitting disease characterised by chronic mucosal and submucosal inflammation of the colon and rectum. Treatment may vary depending upon the extent and severity of inflammation. Broadly speaking medical treatments aim to induce and then maintain remission. Surgery is indicated for inflammatory disease that is refractory to medical treatment or in cases of neoplastic transformation. Approximately 25% of patients with UC ultimately require colectomy. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) has become the standard of care for patients with ulcerative colitis who ultimately require colectomy. This review will examine indications for IPAA, patient selection, technical aspects of surgery, management of complications and long term outcome following this procedure.

- Citation: Bach SP, Mortensen NJ. Ileal pouch surgery for ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(24): 3288-3300

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i24/3288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i24.3288

Colectomy most often follows failure of medical treatment for severe and extensive colitis. Toxic dilatation (colon > 6 cm), perforation and haemorrhage are less common indications. The decision to operate is taken jointly and involves daily communication between gastroenterology and surgical teams. Patients receiving high dose intravenous steroids who have a stool frequency of > 8 per day on the third treatment day are likely to require colectomy[1]. Similarly those with a stool frequency of 3-8 stools per day who have a CRP > 45 mg/L are unlikely to settle. Failure to respond after 5-7 d or any significant deterioration during this period is an indication for colectomy. Patients who initially respond but promptly relapse with the reintroduction of diet are also likely to require colectomy. Pouch surgery should be avoided in the acute setting. It is customary to instead, perform subtotal colectomy with an end ileostomy. The colon is mobilized and vessels taken relatively close to the bowel wall. The sigmoid stump is stapled and left long allowing it to be secured with sutures in the subcutaneous space at the lower pole of the wound. Any stump dehiscence will then result in an easily manageable fistula rather than a pelvic abscess and the sigmoid will be easy to locate at reoperation. A Foley catheter is used to decompress the rectum for a period of 3 or 4 d.

Large bowel malignancy is ultimately thought to complicate UC in 5% of cases. Meta-analysis has estimated that 2% of those with colitis develop cancer at 10 years, increasing to 8% at 20 years and 18% at 30 years[2]. Magnitude of risk may be decreasing secondary to the effects of screening, prophylactic surgery and adoption of maintenance anti-inflammatory therapy[3]. Nonetheless a family history of colorectal cancer[4] and pan-colitis[5,6] currently mark subjects as high risk. Frequency and severity of relapse are also considered significant factors[7]. Those with PSC are at highest risk of colorectal cancer[8].

Discovery of dysplasia in large intestinal mucosal biopsies provides the best surrogate measure of malignant transformation. Patients judged to be at high risk are subject to colonoscopic surveillance with the aim of detecting dysplasia[9]. Dysplasia associated with UC is microscopically classified as either low (LGD) or high (HGD) grade depending upon the degree of cytological and architectural disturbance. Endoscopic classification defines lesions as flat or raised with further subdivision of raised lesions according to their macroscopic appearance. Raised areas resembling conventional adenomas but situated within an area of colitis are designated as adenoma-like lesions or masses (ALMs). These pedunculated or sessile polyps are usually amenable to endoscopic resection[10]. Areas that demonstrate pronounced irregularity are termed dysplasia-associated lesions or masses (DALMs). These include plaques, velvety patches, areas of nodular thickening and broad based masses. Such lesions are typically not endoscopically resectable in their entirety.

The vast majority of UC related lesions are macro-scopically visible, especially following indigo carmine dye-spray[11]. Complete local excision and surveillance yields a good prognosis, irrespective of the degree of dysplasia. Continued surveillance will identify further ALMs in 50%-60% of patients with flat dysplasia arising in only a small proportion (< 5%)[10,11]. DALMs are usually more challenging to endoscopically remove due to their irregular morphology but in cases where local resection is achieved with clear margins this may be all that is required[12]. Endoscopic assessment of the whole colon must be achieved by an experienced practitioner with facility to use dye-spray techniques in order to uncover otherwise ‘occult’ colonic lesions[11]. Indications for proctocolectomy following the discovery of a dysplastic mass in our practise are (A) incomplete excision of that mass or (B) discovery of multifocal flat dysplasia of any grade at sites either near to or remote from the index lesion. Biopsy samples must be taken beyond the perimeter of a sessile mass to uncover patients who possess a wider field change. The incidence of underlying malignancy in those who undergo proctocolectomy for DALM is in the order of 30%-40%[12].

The finding of HGD in otherwise flat mucosa is an indication for proctocolectomy as the risk of underlying malignancy is in the order of 40%[13]. This is a relatively unusual finding as isolated HGD is more often associated with some form of discernable lesion. Management of LGD in the absence of a macroscopic lesion is more controversial as its natural history is still hotly debated. It should be appreciated that there is significant inter-observer variability in the reporting of LGD even amongst experienced gastroenterological histopathologists[14]. One problem is that biopsies taken from regenerative mucosa following an exacerbation of UC may be mistaken for LGD. Some institutions favour immediate proctocolectomy for LGD based upon studies demonstrating a 20% risk of occult malignancy at presentation with 50% disease progression in 5 years[13]. We favour a more conservative approach that consists of intensified surveillance with colonoscopy at 6-monthly intervals even in cases of multifocal flat LGD. We believe that thorough endoscopic examination by an experienced clinician obviates the need for routine colectomy for LGD. This strategy has been safely adopted in specialist centres with rates of disease progression between 3% to 10% at 10 years[14,15].

Three operative strategies are in common use for the definitive surgical treatment of UC patients. (1) Proctocolectomy and end ileostomy removes all diseased tissue at the expense of a permanent stoma. This option is undertaken in patients with poor sphincter function. It is also used in those patients who are happy with their ileostomy following subtotal colectomy and do not wish to consider a pouch. (2) Subtotal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis (IRA) is a compromise procedure in which a minimally diseased rectum is retained. The rectum must be distensible and retain its capacity to act as a reservoir. This can be confirmed using flexible sigmoidoscopy or a contrast enema. There should be no evidence of colonic dysplasia or malignancy. These criteria are seldom met and this option is rarely used. Function is difficult to predict following IRA when one quarter of patients suffer from unacceptable stool frequency as a consequence of persistent rectal inflammation. Long-term endoscopic follow up of the retained rectum is essential due to the risk of malignant change. (3) Finally ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) has become the standard of care for patients with ulcerative colitis who ultimately require colectomy. This procedure was initially developed by Parks and Nichols during the 1970’s[16]. They combined elements of Kock’s continent pouch[17] with a technique of rectal mucosal excision, used for the removal of rectal adenomata and haemangiomata[18,19]. Their ileal pouch reservoir was anastomosed to the dentate line using a per-anal suturing technique[16]. In a relatively short period of time this technique had become the preferred surgical option for treatment of UC. The advent of stapling instruments greatly simplified IPAA surgery, but it remains a complex undertaking with the potential to cause significant morbidity[20]. This approach is popular with patients as it avoids the necessity for a long-term stoma. Pouch surgery aims to deliver 5 or 6 semi-formed bowel motions per day, with no night time evacuation and no incontinence. Successful outcomes are built upon sensible patient selection, clear pre-operative counselling, an operative strategy appropriate to the patient and expedient management of any complications.

‘Elderly’ sphincters were initially considered too weak to undergo the prolonged anal dilatation necessary for mucosectomy and per anal suturing of the IPAA. Introduction of the ‘double stapled’ IPAA technique meant that prolonged anal dilation could be avoided and reports emerged of IPAA in the 50-70 age group[21-26]. Delaney et al[27] found no difference in daytime stool frequency (5-6 stools per day) in 1410 patients < 45 years, compared to 485 over this age with a median follow up of 4.6 years. Nocturnal frequency was a little better in younger subjects (mean 1.4 versus 1.93) during the first year. At one year, episodes of incontinence were reported by one quarter of those below 45 and half of those > 55 years. Night time seepage occurred in one third and one half of patients respectively. Farouk et al[28] found that nocturnal stool frequency, faecal incontinence, protective pad usage and consumption of constipating medication were higher in patients aged 45 or more at the time of IPAA. Pouch function deteriorated over time in older but not younger patients. Nonetheless high levels of satisfaction were achieved amongst older patients despite inferior functional results. In summary, surgical complications and pouch preservation rates appear to be independent of age at operation, whilst continence and quality of life are generally a little worse with advancing years. IPAA surgery is routinely performed in well motivated elderly individuals without symptomatic disturbance of the anal sphincters.

A definitive histopathological diagnosis of UC or Crohn’s is not always possible following colectomy for colitis. In 10%-15% of surgical specimens a diagnosis of indeterminate colitis (IndC) is made[29-31]. Differentiation between UC and Crohn’s is usually made difficult by the presence of severe inflammation. For example transmural ulceration in fulminant UC may mimic that normally associated with Crohn’s disease[32]. Examination of pre-operative biopsy specimens may yield an accurate diagnosis. Alternatively, the behaviour of the retained rectum may be followed. In UC, florid inflammatory changes are typical while in Crohn’s the rectum will tend to improve following diversion[33-36]. Appendiceal orifice inflammation sometimes termed the appendiceal ‘skip lesion’ can be an additional source of confusion[37-39]. This is considered to be a normal variant of UC being found in 24/94 patients (26%) with active subtotal ulcerative colitis[40].

A diagnosis of Crohn’s disease will subsequently be made in 4% to 15% of patients initially labelled as IndC[41]. Clinicians make every effort to define this population prior to embarking upon ileal pouch surgery. While the majority of patients with IndC obtain good results from IPAA surgery, pelvic sepsis and pouch failure may occur more frequently. This is largely due to the emergence of patients with Crohn’s disease. At 10 years 85% of those with IndC retain their pouch. The issue of outcome following IPAA for IndC has been addressed in two major studies. The Mayo Clinic compared outcome after IPAA for patients with IndC (n = 82), versus UC (n = 1355)[41]. More Crohn's disease emerged in those with IndC (15% vs 2%); median follow-up of 7 years. As a consequence pouch failure was significantly higher for the IndC group (27% vs 11%; P < 0.001). Outcome in patients with IndC who did not convert to Crohn’s was similar to those with UC; although more non-Crohn’s IndC patients did manifest pouch fistulas. 85% of pouches were retained at 10 years. Pre-operative features most associated with a subsequent diagnosis of Crohn’s were atypical disease distribution such as skip lesions and rectal sparring. The Cleveland Clinic reported more encouraging results but over a period of just 3 years[42]. A post-operative pathological diagnosis of IndC was recorded in 171/1911 IPAA patients (9%). Pouch failure rates were 3% for both UC and IndC. Conversion to Crohn’s occurred in 4% of IndC versus 0.4% of matched UC controls. While daytime stool frequency was equivalent (6 ×), those with IndC had worse night time frequency (2 ×vs 1 ×) and proportionally more soiling (36% versus 28%). Rates of daytime incontinence did not differ (25% moderate, 1% severe). There was less overall satisfaction with pouch surgery amongst patients with IndC although 93% declared that they would undergo surgery again.

The consensus amongst most surgeons is that patients with bona fide IndC are suitable candidates for pouch surgery if fully informed of the risks involved. Special attention should be paid to any suspicious history of pelvic sepsis or perineal fistula as these patients are more likely to manifest Crohn’s and in our opinion should not be considered for IPAA surgery.

Following ileal pouch surgery for UC a number of patients are found to have Crohn’s disease. The Toronto group reported on 20 such cases from a total of 551 (3%)[43]. 11/20 patients (55%) eventually lost their pouch. Unsuspected Crohn’s disease is a leading cause of pouch failure in several other series[44,45]. Following diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, pouch failure rates increased 9-fold over a baseline figure of 4%[46]. Pouches were generally lost due to unacceptable function or the presence of complex fistulas. It should also be noted that those with Crohn’s who retained the pouch had satisfactory function. A controversial study detailing ten year follow-up of 41 patients with either known colonic Crohn's but no pre-operative perianal or small bowel disease (26/41) or histological features suggestive of Crohn's following panproctocolectomy and IPAA (15/40) reported comparatively favourable results[47]. Early post-operative complications occurred in one quarter, chronic perianal problems in one quarter and pouch failure in 3/41. Function was generally good. Complication rates were proportionally much higher where the diagnosis of Crohn’s was unequivocal and controversy exists in cases where minor pathological criteria are used to establish the diagnosis of Crohn’s. Some argue that this subgroup might be more appropriately labelled as indeterminate. Crohn’s disease remains an absolute contraindication to IPAA for most practitioners as overall failure rates approach 50%. There may be a role for pouch surgery in a highly selected group of patients with Crohn’s colitis who possess a normal anus, have no small bowel disease and are prepared to accept the increased risks of failure and reoperation.

The presence of dysplasia or potentially curable cancer either within the colon or high in the rectum does not preclude IPAA[48,49]. Mucosectomy and a hand-sewn pouch-anal anastomosis rather than stapling are considered for patients with multiple tumours or multifocal dysplasia especially when these lesions encroach upon the rectum. Following mucosectomy dysplastic cells may survive deep within the muscular rectal cuff[50,51] and these may re-present as ‘pouch tumours’[52]. For this reason reconstructive pouch surgery is probably inadvisable when dealing with low rectal tumours.

Arks and Nicholls originally devised a triple limb ‘S’ shaped pouch[16]. This was relatively complicated to construct and suffered from kinking of the efferent limb if this was left too long[53]. Alternative designs have included the high capacity ‘W’ pouch, the H pouch and the ‘J’ pouch. Lewis et al examined factors associated with good functional outcome in S, J and W double stapled pouches in 100 patients[54]. Compliance of the ileal reservoir, a strong anal sphincter and intact anal reflexes correlated with good outcome while pouch design played no part. The majority of surgeons now favour the J pouch due to ease of construction, economical use of terminal ileum and reliable emptying[55]. Functional results are equal to those of other reservoir designs[56-58]. The pouch is formed from the terminal 40 cm of ileum using several applications of a linear, cutting stapler to join the antimesenteric borders of two 20 cm ileal limbs.

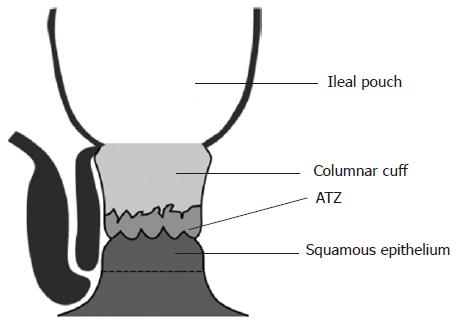

Stripping of the columnar mucosa above the dentate line has been advocated in order to prevent recurrence of UC. Mucosectomy, combined with a per-anal hand-sewn anastomosis allows precise placement of the pouch-anal anastomosis at the dentate line. This technique has several disadvantages. It is certainly more complex to perform and may also predispose to higher rates of sphincter damage and incontinence. A study from Cleveland indicated that faecal incontinence was more common after mucosectomy[59]. In the order of 50% of patients will also experience night time soiling[56,60,61]. Mucosectomy entails excision of the anal transition zone (ATZ), an area of cuboidal epithelium richly innervated by sensory nerve endings that mediate anal sampling reflexes (Figure 1)[62]. Two large series have evaluated the effect of ATZ preservation in slightly different ways. Gemlo et al audited a change in practise from S pouch combined with mucosectomy to J pouch with double stapled anastomosis[63]. Functional results were reported for 235 pouch procedures. Double stapling was associated with a significant reduction in both major and minor night time incontinence, while minor daytime incontinence was also reduced. Choi et al subclassified 138 patients following stapled IPAA according to the epithelial composition of the distal donut[64]. Those with predominantly squamous epithelium (ATZ excised) had significantly lower post operative maximal resting pressures (MxRP) compared to those with mostly columnar epithelium. Values did not however deviate from the normal range. Sphincter length and recto-anal inhibitory reflex preservation did not differ between groups. Surprisingly continence was not reported. These studies tend to suggest that ATZ preservation is a good idea although the role of anal dilation confounds the first study while a lack of functional results hampers the latter.

The ‘double stapled’ IPAA technique preserves the ATZ with no requirement for prolonged anal dilation. A transverse stapler fired from above, separates the rectum from the top of the anal canal. The stapling instrument should be positioned 2-3 cm above the anal margin, a distance roughly equivalent to the length of the distal 2 metacarpals of the index finger. This helps to avoid an error of judgement that places the anastomosis too high resulting in a pouch-rectal anastomosis. A circular EEA stapler inserted via the anus joins the ileal reservoir to the upper anal canal. Proponents of stapling claimed that less sphincter trauma occurs using this technique[65-69] but a series of randomised trials comparing these methods have not demonstrated any functional improvement although some non-significant trends were observed[70-74]. Failure to prove clinical benefit may reflect the small number of patients randomised within each of these trials and the complex nature of defecation.

Stapling itself is not without risk to the anal sphincter. Winter et al[75] reported results of a randomised controlled trial comparing perianal application of 0.2% GTN ointment with placebo in 60 patients prior to circular stapler insertion. GTN significantly reduced intraoperative mean anal resting pressure (MRP) and the need for anal digitation prior to insertion of the circular stapler. Post operative MRP did not deviate from preoperative values and function was excellent at 3 and 12 mo. Following placebo, post operative MRP was significantly reduced and function was worse, even at 12 mo. These findings suggest that local trauma arising from stapler insertion can induce sphincter damage and that pharmacological intervention affords some protection.

Finally, performance of mucosectomy and hand-sewn IPAA is technically more challenging than stapled IPAA. Hand-sewn anastomoses have been associated with higher rates of anastomotic disruption and pelvic sepsis[76] although pouch failure rates are apparently not adversely affected[46]. Many surgeons including ourselves favour the double staple technique as this is the simpler operation; preservation of the ATZ is conceptually appealing and this operation may have a lower risk of morbidity and ultimately failure.

To date most surgeons have favoured creation of a temporary defunctioning loop ileostomy following IPAA surgery as this avoids what can be catastrophic pelvic contamination in the event of anastomotic dehiscence[77]. Pouch failure rates from St Marks were higher in patients without a covering stoma; 15% versus 8%[78], although Toronto have published contrasting figures with less than 1% of one stage pouches failing[43]. To omit a defunctioning ileostomy is an exercise in risk management. Large series indicate that anastomotic separation occurs in approximately 5%-15% of patients[46,79,80] while complication rates for ileostomy closure range from 10% to 30%[81-89]. Small bowel obstruction, wound infection and anastomotic leakage are the most prevalent. In practice we omit stomas in approximately 15% of cases based upon the perceived risks (steroids, nutrition, age, anaemia etc), uneventful surgery and discharge arrangements.

Conventional open surgery utilises a long midline incision for access to the splenic flexure and pelvis. The laparoscopic approach is more elegant as trauma to the abdominal wall is minimised. In the short term wound related complications such as pain and infection may be reduced. Over a more protracted period the risk of symptomatic adhesions and incisional herniation may be diminished. There is little doubt that cosmetic appearance is enhanced. To date rigorous assessment of these endpoints using large clinical trials has been hindered by the relative complexity of these techniques. A prospective randomised controlled trial of hand-assisted laparoscopic colonic mobilisation and open rectal dissection (via an 8 cm Pfannenstiel incision) versus open surgery through the midline in 60 patients showed no difference in post-operative quality of life measurements[90]. While open pelvic dissection is expedient and facilitates distal stapling it may negate some benefits of the laparoscopic approach. Refinement of dissection techniques and the production of dedicated equipment has already greatly facilitated the performance of laparoscopic IPAA in some centres[91]. Accelerated recovery programs have delivered reduced hospital stays for elective IPAA patients somewhat negating the benefits of laparoscopic over open surgery in this regard. In a recent randomised, observer and patient blinded trial, 60 patients underwent elective laparoscopic or open colonic resection with the principles of fast-track rehabilitation applied to both groups[92]. Median postoperative stay was 2 d, with rates of readmission in the order of 20%-25%. More patients thought that their stay was too short following open (30%) versus laparoscopic surgery (17%). Functional outcome did not differ. These data combined with our experience suggest that optimised perioperative management has much to offer the ileal pouch patient.

Fever in a patient recovering from IPAA surgery should arouse suspicion of pelvic sepsis. This remains a relatively common acute complication and failure to react in a timely fashion is likely to compromise pouch function and may eventually lead to failure. Septic complications usually result from anastomotic dehiscence or the presence of an infected pelvic haematoma. Digital examination may reveal the anastomotic defect or localised tenderness overlying an indurated or fluctuant mass. CT or MRI can be used to gauge the extent of sepsis. A trial of broad spectrum antibiotics is appropriate for relatively small abscesses. Treatment may be tailored to the size and nature of the problem. For instance non-operative measures were used to treat 24/131 (18%) cases in a series from Heidelberg, with 2/24 (8%) eventually losing the pouch[93]. Data from Mayo indicate that 11/73 (15%) abscesses were considered ‘early’ and treated with antibiotics alone[94]. All but 3 cases resolved without the need for subsequent surgery. More sizeable collections are considered for radiological drainage and in the series from Mayo an additional 16/73 (22%) cases were aspirated under radiological guidance with only 3 eventually requiring surgical intervention.

Failure to settle would prompt examination under anaesthesia. The anus is inspected using an Eisenhammer anal speculum (Seward, London, UK). Anastomotic breakdown is usually detected without difficulty. The underlying area is then probed to determine the extent of any associated abscess cavity and suction applied to clear its contents. Larger defects may be amenable to digital examination followed by placement of a catheter for irrigation and drainage. Regular re-examination under anaesthetic may be required to be confident that the cavity remains clean. The vagina must also be inspected for evidence of fistulation, especially if the IPAA was stapled. We favour transanal drainage for most episodes of mild to moderate pouch related sepsis though. Other institutions appear to utilise this course of action less frequently with this technique accounting for 8% of treatments for septic episodes in the Mayo series[94] and 33% of those from Heidelberg[93].

At 1 year the rate of pouch related sepsis was 15.6% in 494 consecutive patients treated with stapled J-pouch, mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis from Heidelberg[95]. No patients were diagnosed with Crohn’s disease during this period. Fistulae accounted for 76% of septic events (56% pouch-anal anastomotic; 13% pouch vaginal; 7% proximal pouch), with anastomotic separation (16%) and para-pouch abscesses (8%) constituting the remainder[93]. In contrast 73/1508 (4.8%) of patients from the Mayo Clinic had their recovery complicated by a pelvic collection with pouch fistulae recorded in only 3[94]. In this series a technique of hand-sewn ileal J pouch-anal anastomosis was favoured. The Cleveland Clinic evaluated 1965 IPAA procedures performed for UC (60.7%), IC (27.9%), CD (3.8%) and FAP (0.7%) to conclude that fistula formation occurred in 151 (7%), anastomotic separation in 104 (5%) and pelvic abscess in 109 (5%)[46].

Re-laparotomy is reserved for cases where CT guided drainage and minor surgery have failed to control sepsis and also for those who deteriorate quickly with signs of generalised peritonitis. Major leaks require a proximal diverting loop ileostomy to be formed if one is not already in place. Consideration should be given to exteriorising of the pouch if complete anastomotic disruption has occurred. With gross ischaemia one should aim to resect and exteriorise the ileum.

Rates of pelvic sepsis are much higher for patients with UC undergoing IPAA than for those with FAP who are subject to the same operation. High dose corticosteroids (systemic equivalent of > 40 mg prednisolone per day) have been implicated in the causation of anastomotic failure[95,96]. Steroids may impair healing at the anastomosis, promote infection or merely label patients in poor clinical condition. Other series have failed to demonstrate any association between administration of prolonged courses of high dose corticosteroids (> 20 mg) prior to surgery and the rate of acute septic complications[97]. It is nonetheless customary to avoid IPAA formation and instead perform subtotal colectomy in those patients who are acutely unwell and receiving high dose corticosteroids.

Primary intraluminal haemorrhage may follow formation of a sutured or stapled pouch and it is therefore important to carefully inspect the mucosal surface before the pouch-anal anastomosis is constructed. Reactionary intraluminal haemorrhage, within 24 h of surgery is likely to originate from the suture or staple lines. Irrigation of the pouch with a 1:200 000 adrenaline solution controls the majority of clinically significant haemorrhages[20]. Continued bleeding necessitates a return to the operating room. The pouch is inspected using an Eisenhammer speculum, proctoscope or sigmoidoscope. Suction and irrigation are used to accurately locate the bleeding point which is then sutured or injected with 1:10000 adrenaline solution. Secondary haemorrhage is less common and usually heralds’ pelvic sepsis. The pouch should be inspected in theatre with special attention to the ileoanal anastomosis for evidence of localised anastomotic breakdown. Bleeding points are under-run and collections drained, preferably via the original defect. A small mushroom or Foley catheter may then be placed trans-anally into the cavity.

Intra-abdominal haemorrhage may arise from mesenteric vessels or the pelvic side wall. The rectal stump may bleed following hand-sewn pouch-anal anastomosis. In exceptional circumstances inspection of the lower pelvis is facilitated by detachment of the pouch. The stump is approached endoanally using a Lone Star retractor (Lone Star Medical Products Inc, Houston, Tx). The pouch may then be exteriorised as a left iliac fossa mucous fistula if re-anastomosis is considered unsafe. Uncontrollable pelvic haemorrhage requires packing of the cavity with a second look 48 h later.

Prolonged faecal exposure can lead to adaptive changes within the ileal pouch so that it comes to resemble colonic mucosa[98]. The dependent portion of the pouch is most notably affected[99]. Pouchitis is a relapsing, acute-on-chronic inflammatory condition presenting with diarrhoea (that may be bloody), urgency, abdominal bloating, pain or fever. The aetiology is unknown although recurrent UC in areas of colonic metaplasia and bacterial overgrowth are proposed as possible mechanisms. Patients with new symptoms suggestive of pouchitis should be investigated by endoscopy and biopsy. Endoscopic appearances are initially similar to UC. Punctate haemorrhages, mucous secretion, purulent discharge and superficial ulceration occur later. Histological signs of acute inflammation include polymorphonuclear leucocyte infiltration with superficial ulceration, superimposed onto a background of chronic inflammatory changes[100,101]. Interestingly this condition does not seem to affect pouches in patients with FAP.

In a cohort of 123 consecutive ‘symptomatic’ patients with pouch dysfunction the underlying diagnosis was pouchitis in 34%, irritable pouch syndrome in 28%, unrecognised Crohn’s disease in 15% and cuffitis in 22%[102]. Once these disorders have been excluded and a diagnosis of pouchitis is established it would be reasonable to instigate empirical therapy for relapses, with the caveat that patients who do not promptly settle should return for further endoscopic evaluation.

The cumulative probability of pouchitis, determined on the basis of symptomatology, endoscopy and histopathology in 468 IPAA patients was 20% at one year, 32% at 5 years and 40% at 10 years[103]. No pouchitis occurred following surgery for FAP (7% of the total). The incidence of pouchitis appears to be independent of surgical technique with respect to pouch construction, use of a defunctioning stoma or laparoscopic techniques[58,104-106]. Patients with PSC are more prone to develop pouchitis, with a cumulative probability of 79% at 10 years[107]. Persistence of extraintestinal manifestations of UC has also been linked to an increased risk of developing pouchitis and certain patients exhibit a temporal relationship between their pouchitis and extraintestinal symptoms akin to that described for UC, fuelling speculation that these two inflammatory processes represent variations of the same underlying condition[108]. Perpetuating this theme, smoking is considered to be protective against UC[109] and also reduces the incidence of pouchitis[110,111].

First line therapy is with oral metronidazole or ciprofloxacin. Hurst et al[112] concluded that oral metro-nidazole or ciprofloxacin clinically improved 96% of pouchitis in an institutional series from Chicago. 41/52 subjects were successfully treated using a seven day course of metronidazole 250 mg tds, with a further 8 responding to ciprofloxacin 500 mg bd. Two thirds of patients developed further attacks and 6% became chronic sufferers. The efficacy of metronidazole has been confirmed by three small prospective randomised studies[113-115]. One suggested that ciprofloxacin 500 mg bd for two weeks was more effective than metronidazole[115]. This drug produced no side effects whereas metronidazole had induced either an unpleasant taste, vomiting or transient peripheral neuropathy in 3/9 patients. Maintenance therapy may be effective for those who promptly relapse following cessation of treatment and weekly rotation of antimicrobials may combat resistance to single agents. The probiotic VSL-3 may be taken orally with some evidence that relapse rates are decreased. Two randomised trials have shown relapse rates in the order of 10%-15% at 9-12 mo with VSL-3 versus 94%-100% for placebo[116,117]. This therapeutic agent has also been trialled in a prophylactic capacity following IPAA surgery. At one year 10% of VSL-3 patients had experienced at least one episode of pouchitis in contrast to 40% of those receiving placebo[118]. Those who fail to respond may be offered oral or rectal corticosteroids[100]. Alternatively oral or topical mesalazine may be used. Consideration should be given to removing the pouch where function is very poor as a consequence of chronic pouchitis.

The ATZ forms a relatively small proportion of the anal canal. Conventional double-stapled restorative proctocolectomy leaves 1.5-2.0 cm of columnar epithelium above the ATZ (Figure 1)[119]. Recurrent UC within the columnar cuff is termed ‘cuffitis’ and it arises in 9%-22% of patients[120,121]. Cuffitis may lead to increased stool frequency, bloody discharge, urgency and discomfort. Mesalazine suppositories may be helpful in improving these symptoms[102]. Dysplasia or carcinoma may theoretically arise within unresected columnar mucosa. Reports do exist of adenocarcinomas situated below the level of the IPAA but these lesions are generally associated with the presence of severe dysplasia or malignancy within the original proctocolectomy specimen[52,122-126]. Routine surveillance of the anal canal is not advocated for the first ten years following IPAA unless the patient has a previous history of dysplasia or malignancy[127-130].

In a large series from Toronto the risk SBO outside of the perioperative period was reported as 6% at 1 year, 14% at 5 years and 19% at 10 years[131]. One quarter of these patients experienced more than one episode. Laparotomy was required in one third of patients and in the majority of cases small bowel was adherent to the pelvis or a previous stoma site. 20% of patients who underwent laparotomy and adhesionolysis developed further episodes of SBO. One quarter of these had a further laparotomy. Factors predisposing to SBO were revisional pouch surgery and formation of a defunctioning stoma. Bowel ischaemia was a rare finding and so a non-operative strategy is likely to be safe where signs of ischaemia do not exist. A water soluble contrast enema may help to determine the site, nature and degree of obstruction. This investigation may also be of therapeutic benefit. Alternatively CT with oral contrast provides similar information. Separate reports from the Cleveland[20], Mayo[132] and Lahey[133] Clinic’s, with follow-up of 2 to 3 years document SBO rates of 25%, 17%, and 20% respectively, with operative intervention necessary in 7% of cases.

Several strategies have been devised to prevent adhesion formation. A multicenter randomised controlled trial of the sodium hyaluronate bioresorbable barrier preparation Seprafilm (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA), revealed reduced adhesions to the midline scar following IPAA in cases where this product was used[134]. Unfortunately the incidence of SBO remained unchanged. If applied next to an anastomosis Seprafilm may impair healing[135], a finding that in our view would preclude its use within the pelvis of pouch patients where adhesions commonly give rise to episodes of SBO.

Pelvic sepsis is estimated to complicate 10%-20% of IPAA procedures. Long term manifestations of pouch sepsis include a variety of fistulae (pouch-anal anastomotic, pouch vaginal, pouch perineal or proximal pouch) and anastomotic stenosis. Functional outcome is likely to be worse following pelvic sepsis both in terms of frequency, reliance upon constipating medication and incontinence. Long term ileostomy may be required in some. Persistent pouch fistula, poor function secondary to a compromised anal sphincter or outlet obstruction may all contribute towards pouch failure.

Fistulae arising between the IPAA and vagina occur relatively rarely with an estimated incidence estimated of 3% to 16%[61,136-139]. In a study of 68 patients from St Marks pouch vaginal fistulae originated from either the IPAA (76%), the pouch (13%) or from a cryptoglandular source (10%)[140]. Operative trauma, postoperative pelvic sepsis and undiagnosed Crohn’s disease were implicated. Unsuspected Crohn’s should be actively sought as rates of healing are worse (25% vs 48%) and pouch failure more common (33% vs 14%) amongst this subgroup[139]. Principals of management include local drainage of the tract using a seton with faecal diversion in selected cases based upon the degree of uncontrolled sepsis. Several options are available to the surgeon for definitive treatment. Transanal ileal advancement flap is appropriate for a pouch that remains mobile with success rates reported in the order of 50%[141]. The procedure may be repeated if it initially fails with some success. Transabdominal advancement of the ileoanal anastomosis with closure of the defect is necessary when the pouch cannot be mobilized from below. Per-anal access to fistulae arising within the anal canal may be difficult, especially where an anastomosis has been placed at the anorectal junction. For this reason the transvaginal route is favoured by some as access is easier and damage to the anal sphincters may be avoided[136]. The internal anal opening is exposed through the posterior wall of the vagina. Following this the pouch is mobilized and the defect closed followed by restitution of the vaginal wall and formation of a defunctioning stoma[142]. Fistulae that arise as a consequence of previously unrecognised Crohn’s disease may be treated with infliximab although recurrence remains a problem[143,144].

Anastomotic stricture may complicate leakage, tension or ischaemia at the IPAA[145]. This is estimated to complicate 4% to 18% of cases[20,69,146-148]. It is therefore important to perform an adequate EUA prior to ileostomy closure in addition to the pouchogram. Once the pouch is in circuit symptoms of straining, diarrhoea and anal or abdominal pain suggest stricturing of the anastomosis. It may be possible to attempt dilatation at the time of pouchoscopy. Alternatively application of Hegar’s dilators under anaesthesia successfully treats most cases[149]. It may prove beneficial for the patient to continue to use the dilator for several weeks at home. Particularly long or tight strictures may not respond to these measures. Further biopsies are taken to exclude Crohn’s disease. Per-anal pouch advancement is considered once all sepsis has been eradicated if the pouch is not tethered[141]. This technique is also used to close fistula tracks situated at the level of the stricture. Otherwise re-laparotomy, mobilisation of the pouch with re-anastomosis is the sole option.

Erectile function is a parasympathetic response mediated by the erigent nerves, while ejaculation is a sympathetic event mediated by the hypogastric nerves. These structures may be damaged during pelvic dissection as they lie behind the parietal facial envelope, close to the mesorectal plane. One may avoid contact with the pelvic nerves using a close rectal dissection. This approach is highly vascularised and for this reason many surgeons prefer to dissect in the more anatomical mesorectal plane. Lindsey et al[150] deduced that close rectal dissection conferred no benefit with regard to either impotence or ejaculatory difficulties when compared to dissection in the mesorectal plane. Sexual dysfunction affects 3% of men following pouch surgery and for this reason sperm banking should be recommended[28,150]. Sildenafil (Viagra) has been shown to help erectile dysfunction but will not impact upon retrograde ejaculation[151].

UC commonly affects young females of reproductive age. Neither the disease itself nor the medical treatments currently available (apart from salazopyrin in men) are thought to compromise fertility[152]. Fertility rates are lower in women who have had pouch surgery compared to those who undergo purely medical management. In the order of 40% of women will have difficulty becoming pregnant following IPAA[153]. It may be possible to delay proctectomy until a family has been established or alternatively use of anti-adhesion products may combat tubal obstruction.

Vaginal delivery has been associated with occult sphincter injury in 30% of patients[154]. Females with an ileal pouch might risk incontinence following vaginal delivery. Cleveland clinic has reported that sphincter injury occurs more frequently in those who choose vaginal delivery rather than caesarean section with rates of 50% and 13% respectively but no difference in pouch function was apparent at 5 years[155]. The Mayo Clinic reported that pouch function was unaffected by childbirth in 85 women; median follow up of 8 years[28]. For the duration of the pregnancy stool frequency, incontinence and pad usage gradually increase[156]. Pouch function quickly returning to normal in most cases. A study of 47 deliveries in 29 women from Toronto revealed that stool frequency and incontinence were worse in the third trimester with pouch function quickly returning to normal in 83% of cases[157]. Neither multiple births nor birth weight adversely affected subsequent pouch function. Long-term disturbance in pouch function was seen in a small proportion of females (17%) although this interestingly bore no relation to the method of delivery (Caesarian or vaginal). 24/49 deliveries were by Caesarian section. The authors concluded that obstetric criteria alone should determine mode of delivery. It seems reasonable to conclude that while vaginal delivery confers no functional disadvantage in the medium term we remain concerned that sphincter integrity is indeed compromised. Long-term implications remain unmeasured and therefore uncertain.

Complication rates for IPAA in the order of 30% to 40% are relatively high. Fortunately most of these problems can usually be resolved. Pouch excision or indefinite retention of a defunctioning stoma defines failure. Institutional pouch failure rates have notably fallen over the past 20 years presumably following improvements in patient selection and surgical technique. Long term failure occurs with a frequency of 5%-10%[43,46,78]. A consistent theme that emerges from the large institutional series is that early pouch failure is closely associated with the occurrence of perioperative pelvic sepsis while that occurring later is often secondary to poor function or following an unexpected diagnosis of Crohn’s disease[28,43,46,78,103]. Most failures occur beyond the first year and a steady rate of attrition occurs up to 10 years. Certain operative practises, such as the S pouch design, may have increased pouch failure rates in the past.

The success of redo pouch surgery for UC has improved with approximately three quarters of patients now retaining a functional pouch in the long term[158]. This figure rises further when considering patients with isolated functional impairment[159]. When considering revision one should evaluate the sphincters, assess pelvic soft tissue compliance, make a judgement regarding the likely diagnosis (Crohn’s or UC) and determine the patient's general health and wishes. It is clear that redo-IPAA surgery may benefit patients with an excessively long efferent ileal spout[159-161] or those with a tortuous stricture[162]. It is perhaps less clear whether revision is as beneficial to those with ongoing septic complications[149,163]. Of 101 pouch revisions performed at the Cleveland clinic the original cause of failure was listed as perineal or pouch vaginal fistula (47%), pouch dysfunction including a long efferent limb (36%), chronic anastomotic leak (27%), anastomotic stricture (22%) or unclassified (6%)[164]. Pathological evidence of Crohn’s disease was noted in 4 patients prior to revisional surgery and a further 15 following its completion. New pouches were fashioned in 28 patients with the rest undergoing revision in order to preserve bowel length. Outcome data were available for 85 patients with pouch survival rates at 5 years of 79% for UC and 53% for Crohn’s. Continuing sepsis was present in 64% of cases at the time of revision but this did not prejudice the outcome. Stool frequency was 6.3 ± 2.8 by day and 2.0 ± 1.9 at night. Values were higher where a new pouch had been constructed. Faecal seepage occurred in 50% by day and 69% at night. Complications arising as a result of redo-IPAA occurred in 46% of patients. These results indicate that even in the best hands redo-IPAA surgery carries an appreciable morbidity rate. Not surprisingly outcomes are worse both in terms of overall failure and function when compared to first time surgery; nonetheless this procedure remains a valid alternative to a defunctioning stoma or pouch excision.

When faced with the proposition of removing an ileoanal pouch one should consider that 62% of 68 cases treated at St Marks suffered significant morbidity and one patient died[165]. Pouch failure was attributed to sepsis (50%), poor function (35%), pouchitis (8%) or an assortment of other causes. Salvage had been attempted in 82% of cases prior to excision. The single most common complication following pouch excision was non-healing of the perineal wound with an incidence of 40% at 6 mo and 10% at 12 mo. Between 1 and 6 procedures (median 2) were performed per person to facilitate healing. The risk of readmission at 1 and 5 years was 38% and 58% respectively with 20% of patients requiring reoperation for small bowl obstruction, stoma complications or haemorrhage. A technique of close pouch dissection was used to avoid impotence. Unfortunately 7% of males ultimately suffered from this complication. The success of redo pouch surgery for UC has improved with approximately half to three quarters of patients now retaining a functional pouch in the long term. When considering revision one should evaluate the sphincters, assess pelvic soft tissue compliance, make a judgement regarding the likely diagnosis (Crohn’s or UC) and determine the patient's general health and wishes. It is clear that redo-IPAA surgery may benefit patients with an excessively long efferent ileal spout or those with a tortuous stricture. It is perhaps less clear whether revision is as beneficial to those with ongoing septic complications. Even in the best hands redo-IPAA surgery carries an appreciable morbidity rate. Not surprisingly outcomes are worse both in terms of overall failure and function when compared to first time surgery; nonetheless this procedure remains a valid alternative to a defunctioning stoma or pouch excision.

The introduction of IPAA has revolutionised treatment of ulcerative colitis. Over the past 30 years we have witnessed convergence of operative technique towards a stapled J pouch design with stapled ileo-anal anastomosis. This is perhaps the fastest and easiest way to create the IPAA. Anastomotic design will hopefully evolve further in order to minimise post-operative complications, reduce the frequency of bowel movements and improve continence. One stage laparoscopic IPAA has already set new standards of cosmesis and may reduce the burden of adhesional small bowel obstruction. Perennial problems such as evolving Crohn’s disease still produce substantial morbidity amongst a minority of patients. We look forward to the development of genetic markers that identify this subgroup at an early stage so that pouch surgery may be either avoided or prophylactic therapy initiated to improve outcome. Pouchitis is a more common problem for which we hope that determination of the relevant aetiological factors may allow prophylaxis. Ileo-anal pouch surgery has quickly become the standard of surgical care for chronic UC and should be considered a major success in the field of gastrointestinal surgery.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Travis SP, Farrant JM, Ricketts C, Nolan DJ, Mortensen NM, Kettlewell MG, Jewell DP. Predicting outcome in severe ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;38:905-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48:526-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 2115] [Article Influence: 84.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Rubio CA, Befrits R, Ljung T, Jaramillo E, Slezak P. Colorectal carcinoma in ulcerative colitis is decreasing in Scandinavian countries. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:2921-2924. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Nuako KW, Ahlquist DA, Mahoney DW, Schaid DJ, Siems DM, Lindor NM. Familial predisposition for colorectal cancer in chronic ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1079-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1228-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1294] [Cited by in RCA: 1202] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Colorectal cancer risk and mortality in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1444-1451. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Rutter M, Saunders B, Wilkinson K, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm M, Williams C, Price A, Talbot I, Forbes A. Severity of inflammation is a risk factor for colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:451-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 895] [Cited by in RCA: 893] [Article Influence: 40.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 8. | Soetikno RM, Lin OS, Heidenreich PA, Young HS, Blackstone MO. Increased risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:48-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Eaden JA, Mayberry JF. Guidelines for screening and surveillance of asymptomatic colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2002;51 Suppl 5:V10-V12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Odze RD, Farraye FA, Hecht JL, Hornick JL. Long-term follow-up after polypectomy treatment for adenoma-like dysplastic lesions in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:534-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Schofield G, Forbes A, Price AB, Talbot IC. Pancolonic indigo carmine dye spraying for the detection of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2004;53:256-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm MA, Williams CB, Price AB, Talbot IC, Forbes A. Thirty-year analysis of a colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1030-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 492] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bernstein CN. Natural history and management of flat and polypoid dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35:573-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lim CH, Dixon MF, Vail A, Forman D, Lynch DA, Axon AT. Ten year follow up of ulcerative colitis patients with and without low grade dysplasia. Gut. 2003;52:1127-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rubio CA, Befrits R. Low-grade dysplasia in flat mucosa in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1494; author reply 1494-1495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Parks AG, Nicholls RJ. Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1978;2:85-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 968] [Cited by in RCA: 927] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kock NG. Intra-abdominal "reservoir" in patients with permanent ileostomy. Preliminary observations on a procedure resulting in fecal "continence" in five ileostomy patients. Arch Surg. 1969;99:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 445] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jeffery PJ, Hawley PR, Parks AG. Colo-anal sleeve anastomosis in the treatment of diffuse cavernous haemangioma involving the rectum. Br J Surg. 1976;63:678-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Parks AG. Transanal technique in low rectal anastomosis. Proc R Soc Med. 1972;65:975-976. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Schroeder TK. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 947] [Cited by in RCA: 858] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lewis WG, Sagar PM, Holdsworth PJ, Axon AT, Johnston D. Restorative proctocolectomy with end to end pouch-anal anastomosis in patients over the age of fifty. Gut. 1993;34:948-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dayton MT, Larsen KR. Should older patients undergo ileal pouch-anal anastomosis? Am J Surg. 1996;172:444-447; discussion 444-448;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bauer JJ, Gorfine SR, Gelernt IM, Harris MT, Kreel I. Restorative proctocolectomy in patients older than fifty years. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:562-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tan HT, Connolly AB, Morton D, Keighley MR. Results of restorative proctocolectomy in the elderly. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1997;12:319-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Reissman P, Teoh TA, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Functional outcome of the double stapled ileoanal reservoir in patients more than 60 years of age. Am Surg. 1996;62:178-183. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Takao Y, Gilliland R, Nogueras JJ, Weiss EG, Wexner SD. Is age relevant to functional outcome after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis?: prospective assessment of 122 cases. Ann Surg. 1998;227:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Delaney CP, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Hammel J, Church JM, Hull TL, Senagore AJ, Strong SA, Lavery IC. Prospective, age-related analysis of surgical results, functional outcome, and quality of life after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2003;238:221-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Farouk R, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, Dozois RR, Browning S, Larson D. Functional outcomes after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2000;231:919-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Price AB. Overlap in the spectrum of non-specific inflammatory bowel disease--'colitis indeterminate'. J Clin Pathol. 1978;31:567-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | McIntyre PB, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, Dozois RR, Beart RW. Indeterminate colitis. Long-term outcome in patients after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:51-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Marcello PW, Schoetz DJ, Roberts PL, Murray JJ, Coller JA, Rusin LC, Veidenheimer MC. Evolutionary changes in the pathologic diagnosis after the ileoanal pouch procedure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:263-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Warren BF. Classic pathology of ulcerative and Crohn's colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:S33-S35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Deutsch AA, McLeod RS, Cullen J, Cohen Z. Results of the pelvic-pouch procedure in patients with Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:475-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Warren BF, Shepherd NA, Bartolo DC, Bradfield JW. Pathology of the defunctioned rectum in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1993;34:514-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Harper PH, Truelove SC, Lee EC, Kettlewell MG, Jewell DP. Split ileostomy and ileocolostomy for Crohn's disease of the colon and ulcerative colitis: a 20 year survey. Gut. 1983;24:106-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Edwards CM, George B, Warren BF. Diversion colitis: new light through old windows. Histopathology. 1999;35:86-87. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Groisman GM, George J, Harpaz N. Ulcerative appendicitis in universal and nonuniversal ulcerative colitis. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:322-325. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Cohen T, Pfeffer RB, Valensi Q. "Ulcerative appendicitis" occurring as a skip lesion in chronic ulcerative colitis; report of a case. Am J Gastroenterol. 1974;62:151-155. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Channer JL, Smith JH. 'Skip lesions' in ulcerative colitis. Histopathology. 1990;17:286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Yang SK, Jung HY, Kang GH, Kim YM, Myung SJ, Shim KN, Hong WS, Min YI. Appendiceal orifice inflammation as a skip lesion in ulcerative colitis: an analysis in relation to medical therapy and disease extent. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:743-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Yu CS, Pemberton JH, Larson D. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with indeterminate colitis: long-term results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1487-1496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Delaney CP, Remzi FH, Gramlich T, Dadvand B, Fazio VW. Equivalent function, quality of life and pouch survival rates after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for indeterminate and ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2002;236:43-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | MacRae HM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z, O'Connor BI, Ton EN. Risk factors for pelvic pouch failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Peyrègne V, Francois Y, Gilly FN, Descos JL, Flourie B, Vignal J. Outcome of ileal pouch after secondary diagnosis of Crohn's disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2000;15:49-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Sagar PM, Dozois RR, Wolff BG. Long-term results of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:893-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Fazio VW, Tekkis PP, Remzi F, Lavery IC, Manilich E, Connor J, Preen M, Delaney CP. Quantification of risk for pouch failure after ileal pouch anal anastomosis surgery. Ann Surg. 2003;238:605-614; discussion 614-617. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Regimbeau JM, Panis Y, Pocard M, Bouhnik Y, Lavergne-Slove A, Rufat P, Matuchansky C, Valleur P. Long-term results of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for colorectal Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:769-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Ziv Y, Fazio VW, Strong SA, Oakley JR, Milsom JW, Lavery IC. Ulcerative colitis and coexisting colorectal cancer: recurrence rate after restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1:512-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Taylor BA, Wolff BG, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Pemberton JH, Beart RW. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis and familial polyposis coli complicated by adenocarcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:358-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Heppell J, Weiland LH, Perrault J, Pemberton JH, Telander RL, Beart RW. Fate of the rectal mucosa after rectal mucosectomy and ileoanal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:768-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | O'Connell PR, Pemberton JH, Weiland LH, Beart RW, Dozois RR, Wolff BG, Telander RL. Does rectal mucosa regenerate after ileoanal anastomosis? Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Rodriguez-Sanjuan JC, Polavieja MG, Naranjo A, Castillo J. Adenocarcinoma in an ileal pouch for ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:779-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Liljeqvist L, Lindquist K. A reconstructive operation on malfunctioning S-shaped pelvic reservoirs. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:506-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Lewis WG, Miller AS, Williamson ME, Sagar PM, Holdsworth PJ, Axon AT, Johnston D. The perfect pelvic pouch--what makes the difference? Gut. 1995;37:552-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Utsunomiya J, Iwama T, Imajo M, Matsuo S, Sawai S, Yaegashi K, Hirayama R. Total colectomy, mucosal proctectomy, and ileoanal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1980;23:459-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 525] [Cited by in RCA: 462] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | McHugh SM, Diamant NE, McLeod R, Cohen Z. S-pouches vs. J-pouches. A comparison of functional outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:671-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Johnston D, Williamson ME, Lewis WG, Miller AS, Sagar PM, Holdsworth PJ. Prospective controlled trial of duplicated (J) versus quadruplicated (W) pelvic ileal reservoirs in restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;39:242-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Oresland T, Fasth S, Nordgren S, Hallgren T, Hultén L. A prospective randomized comparison of two different pelvic pouch designs. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:986-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Tuckson W, Lavery I, Fazio V, Oakley J, Church J, Milsom J. Manometric and functional comparison of ileal pouch anal anastomosis with and without anal manipulation. Am J Surg. 1991;161:90-95; discussion 95-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Pemberton JH, Kelly KA, Beart RW, Dozois RR, Wolff BG, Ilstrup DM. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Long-term results. Ann Surg. 1987;206:504-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 307] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Wexner SD, Jensen L, Rothenberger DA, Wong WD, Goldberg SM. Long-term functional analysis of the ileoanal reservoir. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:275-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Miller R, Bartolo DC, Orrom WJ, Mortensen NJ, Roe AM, Cervero F. Improvement of anal sensation with preservation of the anal transition zone after ileoanal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:414-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Gemlo BT, Belmonte C, Wiltz O, Madoff RD. Functional assessment of ileal pouch-anal anastomotic techniques. Am J Surg. 1995;169:137-141; discussion 141-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Choi HJ, Saigusa N, Choi JS, Shin EJ, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. How consistent is the anal transitional zone in the double-stapled ileoanal reservoir? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:116-120. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Heald RJ, Allen DR. Stapled ileo-anal anastomosis: a technique to avoid mucosal proctectomy in the ileal pouch operation. Br J Surg. 1986;73:571-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Sagar PM, Holdsworth PJ, Johnston D. Correlation between laboratory findings and clinical outcome after restorative proctocolectomy: serial studies in 20 patients with end-to-end pouch-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1991;78:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Sugerman HJ, Newsome HH. Stapled ileoanal anastomosis without a temporary ileostomy. Am J Surg. 1994;167:58-65; discussion 65-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Sugerman HJ, Newsome HH, Decosta G, Zfass AM. Stapled ileoanal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and familial polyposis without a temporary diverting ileostomy. Ann Surg. 1991;213:606-617; discussion 617-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Michelassi F, Lee J, Rubin M, Fichera A, Kasza K, Karrison T, Hurst RD. Long-term functional results after ileal pouch anal restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: a prospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2003;238:433-441; discussion 442-445. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Luukkonen P, Järvinen H. Stapled vs hand-sutured ileoanal anastomosis in restorative proctocolectomy. A prospective, randomized study. Arch Surg. 1993;128:437-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Hallgren TA, Fasth SB, Oresland TO, Hultén LA. Ileal pouch anal function after endoanal mucosectomy and handsewn ileoanal anastomosis compared with stapled anastomosis without mucosectomy. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:915-921. [PubMed] |

| 72. | Choen S, Tsunoda A, Nicholls RJ. Prospective randomized trial comparing anal function after hand sewn ileoanal anastomosis with mucosectomy versus stapled ileoanal anastomosis without mucosectomy in restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 1991;78:430-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | McIntyre PB, Pemberton JH, Beart RW, Devine RM, Nivatvongs S. Double-stapled vs. handsewn ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:430-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Reilly WT, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, Nivatvongs S, Devine RM, Litchy WJ, McIntyre PB. Randomized prospective trial comparing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis performed by excising the anal mucosa to ileal pouch-anal anastomosis performed by preserving the anal mucosa. Ann Surg. 1997;225:666-676; discussion 676-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Winter DC, Murphy A, Kell MR, Shields CJ, Redmond HP, Kirwan WO. Perioperative topical nitrate and sphincter function in patients undergoing transanal stapled anastomosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:697-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Ziv Y, Fazio VW, Church JM, Lavery IC, King TM, Ambrosetti P. Stapled ileal pouch anal anastomoses are safer than handsewn anastomoses in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg. 1996;171:320-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Williamson ME, Lewis WG, Sagar PM, Holdsworth PJ, Johnston D. One-stage restorative proctocolectomy without temporary ileostomy for ulcerative colitis: a note of caution. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1019-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Tulchinsky H, Hawley PR, Nicholls J. Long-term failure after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2003;238:229-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Milsom JW, Lavery IC, Oakley JR, Fabre JM. Omission of temporary diversion in restorative proctocolectomy--is it safe? Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:1007-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Galandiuk S, Wolff BG, Dozois RR, Beart RW. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis without ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:870-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Wong KS, Remzi FH, Gorgun E, Arrigain S, Church JM, Preen M, Fazio VW. Loop ileostomy closure after restorative proctocolectomy: outcome in 1,504 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:243-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Edwards DP, Chisholm EM, Donaldson DR. Closure of transverse loop colostomy and loop ileostomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1998;80:33-35. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Winslet MC, Barsoum G, Pringle W, Fox K, Keighley MR. Loop ileostomy after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis--is it necessary? Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:267-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Wexner SD, Taranow DA, Johansen OB, Itzkowitz F, Daniel N, Nogueras JJ, Jagelman DG. Loop ileostomy is a safe option for fecal diversion. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:349-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Hosie KB, Grobler SP, Keighley MR. Temporary loop ileostomy following restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 1992;79:33-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Senapati A, Nicholls RJ, Ritchie JK, Tibbs CJ, Hawley PR. Temporary loop ileostomy for restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 1993;80:628-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Lewis P, Bartolo DC. Closure of loop ileostomy after restorative proctocolectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72:263-265. [PubMed] |

| 88. | Mann LJ, Stewart PJ, Goodwin RJ, Chapuis PH, Bokey EL. Complications following closure of loop ileostomy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1991;61:493-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Phang PT, Hain JM, Perez-Ramirez JJ, Madoff RD, Gemlo BT. Techniques and complications of ileostomy takedown. Am J Surg. 1999;177:463-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Maartense S, Dunker MS, Slors JF, Cuesta MA, Gouma DJ, van Deventer SJ, van Bodegraven AA, Bemelman WA. Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2004;240:984-991; discussion 991-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Larson DW, Cima RR, Dozois EJ, Davies M, Piotrowicz K, Barnes SA, Wolff B, Pemberton J. Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes of laparoscopic ileal-pouch-anal anastomosis: a single institutional case-matched experience. Ann Surg. 2006;243:667-670; discussion 670-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Basse L, Jakobsen DH, Bardram L, Billesbølle P, Lund C, Mogensen T, Rosenberg J, Kehlet H. Functional recovery after open versus laparoscopic colonic resection: a randomized, blinded study. Ann Surg. 2005;241:416-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Heuschen UA, Allemeyer EH, Hinz U, Lucas M, Herfarth C, Heuschen G. Outcome after septic complications in J pouch procedures. Br J Surg. 2002;89:194-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Farouk R, Dozois RR, Pemberton JH, Larson D. Incidence and subsequent impact of pelvic abscess after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1239-1243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |