INTRODUCTION

Human fascioliasis is a rare encountered parasitic infection that has been reported endemic in some parts of the Far and Middle East, including Turkey[1]. Extrahepatobiliary localization of the parasite is very uncommon. Until recently, extrahepatic fascioliasis has been reported in the subcutaneous tissue[2], brain[3], lungs[4], epididymis[2], inguinal lymph nodes[5] and in gastrointestinal system organs like the stomach[6] and the cecum[7]. Herein, we present a strange manifestation of the fasciola infection in a site other than the liver. This is the second ectopic fascioliasis case mimicking a colonic tumor in the English medical literature.

CASE REPORT

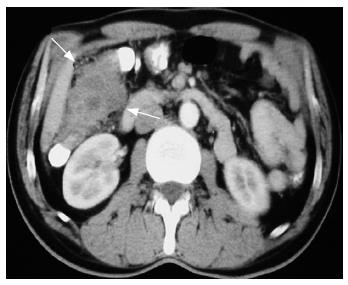

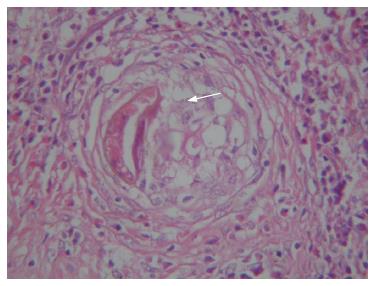

A 55-year-old male patient was admitted to a local hospital with a 1-year history of abdominal pain worsening after meals. The patient had no history of any major illnesses. Physical examination revealed no pathology and abdominal ultrasonography (US) showed gallstones in the gallbladder. He was treated symptomatically. Despite treatment, the abdominal pain continued and an abdominal computerized tomography (CT) was carried out which revealed a 4cm × 7 cm intraluminal mass originating from the ascending colon, adjacent to the right kidney and the liver, infiltrating the pericolic fat (Figure 1). He was hospitalized for further investigation. Physical examination again revealed no pathology and laboratory findings, including liver function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white blood cell count and tumor markers, were unremarkable. Eosinophil ratio was normal. Since it was reported that the identification of the nature of the mass was not possible radiologically, a colonoscopy was planned which could not be carried out, unfortunately. During admission, the patient developed mechanical bowel obstruction and demanded immediate surgical exploration. A solid mass, originating from the right colon, 7 cm × 5 cm in diameter and invading the serosa was found during surgery. All other intraabdominal organs, including the liver, were found without particularity. Following exploration, a right hemicolectomy - ileotransversotomy and cholecystectomy was performed. The histopathological examination of the colonic specimen revealed granulomas with central necrosis and Charcot Leyden crystals, surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils secondary to fasciola hepatica. Trapped egg was found inside the granuloma (Figure 2). Serological examination with the indirect hemagglutination test verified fascioliasis with a titre of 1/640. The patient's postoperative course was uneventful. Bithionol therapy was scheduled after surgery and serological examination became negative, while the follow-up abdominal tomography revealed no abnormality, after one year.

Figure 1 Computerized tomography revealed a 4 cm x 7 cm intraluminal mass originating from the ascending colon, adjacent to the right kidney and the liver, infiltrating the pericolic fat.

Figure 2 Histological study shows a trapped egg (arrow) in the center of a granuloma.

Eosinophilia is striking around this structure (HE, × 400).

DISCUSSION

Fasciola hepatica, a zoonotic disease, infects a wide variety of mammalian hosts all around the world[8]. The infectious form of the trematode is the metacercaria which reaches the stomach by ingestion of infected food or water. Here, the outer shell of the metacercaria melts and the young trematode becomes loose. The trematode penetrates the intestinal wall to reach the periton, stays there for a few days and climbs to the surface of the liver. It penetrates the capsule of Glisson and enters the liver parenchyma to reach the bile ducts. Another way to reach the liver parenchyma is by blood or lymphatic circulation[9,10].

The usual symptoms are fever of unknown origin, abdominal pain, biliary colic and cholangitis, which are caused by the migration of the trematode to the biliary tract[11]. As the parasite grows it can cause bleeding, necrosis and inflammation following by fibrosis of the hepatocyte[12-14]. The diagnosis is usually based upon the detection of the eggs in the duodenal aspirate and feces. Serological tests are the main diagnostic tests, which become important in especially suspicious cases. The diagnosis can be verified 95%-100% by the enzyme linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA)[14]. Radiological findings of fascioliasis are based mainly on US and CT[8,15]. There are recent studies reporting magnetic resonance imaging to be useful in the diagnosis of fasciola hepatica[16,17]. CT can be useful in the diagnosis and the findings can be pathognomonic in almost 90% of the patients[15].

A strange manifestation of fascioliasis is the disease in sites other than the liver. The precise route of migration toward ectopic sites is unknown, and various theories have been formulated, including the migration through blood vessels or through the soft tissues[9,18,19]. Until recently, extrahepatic fascioliasis has been reported in foci like the subcutaneous tissue, brain, lungs, epididymis, inguinal lymph nodes, stomach and the cecum. Nevertheless, there has been only one data concerning a report of colonic fascioliasis[7]. All preoperative diagnostic work-up in the current case failed to point out the fascioliasis. Emergency surgery was performed, since a diagnosis of an obstructing colon tumor was suspected. Postoperative work-up, including the histopathological and serological assay, confirmed the presence of the parasitic disease. When reanalyzing the preoperative abdominal CT retrospectively, it was reported that the mass could be regarded as a possible inflammatory mass which could have led us to the diagnosis of a non-malignant tumor. In the eye of this knowledge, whether the management would change is a matter of debate. Another point is that we might insist on colonoscopy that could reveal differentiation of the mass. Besides, maybe an effective colonoscopy could lead to the performance of a serological test for parasitic investigation before surgery. Whether resective surgery was too radical in this case is another matter of debate.

Eosinophilia in fascioliasis cases is striking and almost always present. This is usually the way most fascioliasis cases are defined during routine screening[5]. Unfortunately, this could not be dated in our patient. The presence of Eosinophilia might be a clue, resulting in a carefully diagnostic work-up to rule out the parasitosis.

Since signs and symptoms of fascioliasis may be confused with a wide variety of disorders, including hepatobiliary and extrahepatobiliary, diagnosis and treatment are often problematic and delayed[7]. A long list of differential diagnosis is essential. Especially in countries where the disease is presumed to be endemic, a high index of suspicion is of utmost importance. It should be considered in cases from endemic areas with a history of ingestion of watercress. Besides, it must be kept in mind that drinking contaminated water is also a way of acquiring the disease. Until recently, seroprevalance of the parasite in Eastern Turkey was reported to be 2.78% independent of age, educational and socioeconomic status[20]. In Turkey 214 cases of fascioliasis have been reported from 1932 to 2003. It is believed that the number of reported cases have increased with the use of serological methods in Turkey, which had been started after 1999[21].

To conclude, since the clinical spectrum of fascioliasis is broad and patients may present with extrahepatic symptomatology, a high index of suspicion is required. Ectopic fascioliasis should be kept in mind and added to the differential diagnosis of colorectal tumors.