Published online Dec 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i48.7864

Revised: August 28, 2006

Accepted: November 24, 2006

Published online: December 28, 2006

AIM: To investigate the therapeutic effectiveness of colonic exclusion and combined therapy for refractory constipation.

METHODS: Thirty-two patients with refractory constipation were randomly divided into treatment group (n = 14) and control group (n = 18). Fourteen patients in treatment group underwent colonic exclusion and end-to-side colorectal anastomosis. Eighteen patients in control group received subtotal colectomy and end-to-end colorectal anastomosis. The therapeutic effects of the operations were assessed by comparing the surgical time, incision length, volume of blood losses, hospital stay, recovery rate and complication incidence. All patients received long-term follow-up.

RESULTS: All operations were successful and patients recovered fully after the operations. In comparison of treatment group and control group, the surgical time (h), incision length (cm), volume of blood losses (mL), hospital stay (d) were 87 ± 16 min vs 194 ± 23 min (t = 9.85), 10.4 ± 0.5 cm vs 21.2 ± 1.8 cm (t = 14.26), 79.5 ± 31.3 mL vs 286.3 ± 49.2 mL (t = 17.24), and 11.8 ± 2.4 d vs 18.6 ± 2.6 d (t = 6.91), respectively (P < 0.001 for all). The recovery rate and complication incidence were 85.7% vs 88.9% (P = 0.14 > 0.05), 21.4% vs 33.3% (P = 0.73 > 0.05), respectively.

CONCLUSION: Colonic exclusion has better therapeutic efficacy on refractory constipation. It has many advantages such as shorter surgical time, smaller incision, fewer blood losses and shorter hospital stay.

- Citation: Peng HY, Xu AZ. Colonic exclusion and combined therapy for refractory constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(48): 7864-7868

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i48/7864.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i48.7864

Refractory constipation is a common clinical symptom. Because it is very obstinate and its etiological factors are unclear, it is difficult for medical workers to treat the patients. The problem of difficult defecation usually cannot be solved with drug treatment. According to our experience, surgical treatment is suggested for the patients who are unresponsive to cathartics or who need to ingest exceeding cathartics to evacuate their bowels. There are many conventional surgical methods, such as total colectomy, subtotal colectomy, hemicolectomy, etc. However, the operation time of these surgical methods is too long. Besides, these surgical methods with big trauma will give rise to many postoperative complications and negatively affect the quality of the patients’ lives. Moreover, the very aged patients cannot bear these operations and their treatment is far from satisfactory[1]. Since 1998 we have adopted colonic exclusion with colorectal anastomosis and treated 14 patients of refractory constipation. All of them were satisfied with the therapeutic effects. The quality of patients’ lives had been improved significantly after operations. Our clinical practice demonstrates that colonic exclusion is a safe and feasible operation. It has good therapeutic effects, shorter surgical time, and lower complication incidences.

Thirty-two patients were diagnosed as refractory constipation between January 1998 and April 2006. These patients received surgical intervention after ineffective medical treatment. They were divided into two groups randomly. There were two males and twelve females in treatment group (n = 14). Their ages ranged from 31 to 77 years with a mean age of 45. Their courses of disease ranged from three to thirty years with 12 years on average. Among them, ten patients had rectocele, and eight patients had rectal prolapse. Five males and thirteen females entered control group (n = 18). Their ages ranged from 28 to 75 years with a mean age of 51. Their courses of disease ranged from four to thirty-five years with 13 on average. Eleven patients had rectocele among them. There were no statistical differences in age and courses of disease between the two groups.

All patients had difficult defecation for three or more than three years. Some serious cases had difficult defecation beyond thirty years. They had been ingesting cathartics or other medicine for a long time. Patients usually complained of headache, general malaise, decreased appetite, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, straining at stooling, incomplete evacuation, or a need for digital manipulation to defecate. The frequency of defecation was about once four to eight days.

Diagnostic criteria included (1) The time of difficult defecation exceeded one year; (2) The stool frequency was below three times per week for at least three months in one year. Patients had difficult defecation accompanied by abdominal pain and abdominal distension. Stools hardened gradually to form hard feces; (3) Digital rectal examination suggested that the patient had fecal impaction accompanied by anal stenosis, hemorrhoid, and rectal prolapse; (4) Gastrointestinal transit test showed that colonic transit became slower. Rectocele and long-winded sigmoid colon were confirmed with defecography; (5) Gastrointestinal organic diseases were excluded by electronic colonoscopy.

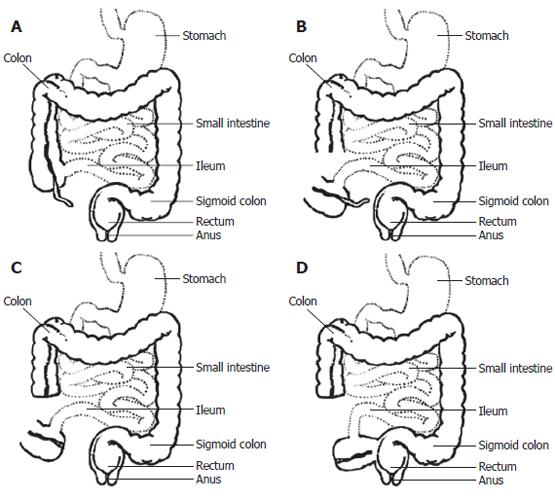

Patients in treatment group were in a lithotomy position after general anesthesia. We adopted median abdominal incision around the umbilicus. After entering the abdominal cavity, the peritoneal reflexion was severed, and the anterior wall of the rectum was dissected until the rectocele was exposed. We sewed three or four needles with 3-0 absorbable suture perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the rectum, and subsequently sewed two needles along the longitudinal axis of the rectum. The needles should penetrate the serous membrane and muscular layer so as to restore the anterior wall of the rectum. Cautions must be taken not to penetrate the mucous membrane at the same time. Freeing of distal ileum, ileocecal junction and partial ascending colon allowed us to obtain enough slack proximal colon, which guaranteed a tension-free anastomosis. Colonic blood supply was carefully examined about 4 to 6 cm away from the ileocecal junction, and the ascending colon was transected at the chosen level with good blood supply. The distal colon was closed by U-shaped sutures to lay the indwelling colon in the abdominal cavity. Vermiform appendix was severed from the cecum by a conventional method. The proximal ascending colon and cecum were moved to the pelvic cavity in anticlockwise, and then end-to-side colorectal anastomosis was performed with stapler under peritoneal reflexion. Long-winded sigmoid colon was resected simultaneously. The rectum was raised and fixed with the lateral side of pelvic peritoneum in order to suspend the rectum. The basement of pelvic cavity was reestablished and the posterior peritoneal space was closed. Finally the abdominal cavity was closed after checking surgical instruments and gauzes. It was unnecessary to place drainage tubes in the abdominal cavity to prevent postoperative adhesion (Figure 1).

The patients in control group had median abdominal incision. After entering the abdominal cavity, peritoneal reflexion was severed. The anterior wall of the rectum was dissected until the rectocele was exposed. Then the rectocele was restored as above. The whole colon was freed. Vermiform appendix was severed. Subsequently the colon from the ascending colon, which was about 4 to 6 cm away from ileocecal valve, to sigmoid colon was resected subtotally. The proximal ascending colon and cecum were moved to the pelvic cavity in anticlockwise, and then the proximal ascending colon was end-to-end anastomosed with the rectum. The abdominal cavity was closed after closure of the posterior peritoneal space. We also did not place drainage tubes in the abdominal cavity.

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. They were entered into SPSS 12.0 statistical package. Statistical comparison was done with group t-test and Fisher exact probabilities in 2 × 2 table. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The surgical time (h), incision length (cm), volume of blood losses (ml), hospital stay (d) were 87 ± 16 min, 10.4 ± 0.5 cm, 79.5 ± 31.3 mL, 11.8 ± 2.4 d in treatment group, and 194 ± 23 min, 21.2 ± 1.8 cm, 286.3 ± 49.2 mL, 18.6 ± 2.6 d in control group, respectively (P < 0.001) (Table 1). The treatment group had several advantages such as shorter surgical time, smaller incision, less blood losses and shorter hospital stay. Compared with the control group, colonic exclusion could reduce local trauma for many patients.

| Group | Cases | Surgical time | Incision length | Blood loss | Hospital stay | Recovery | Improvement | Complication |

| (n) | (min) | (cm) | (mL) | (d) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Treatment group | 14 | 87 ± 16 | 10.4 ± 0.5 | 79.5 ± 31.3 | 11.8 ± 2.4 | 12 (85.7) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (21.4) |

| Control group | 18 | 194 ± 23 | 21.2 ± 1.8 | 286.3 ± 49.2 | 18.6 ± 2.6 | 16 (88.9) | 2 (11.1) | 6 (33.3) |

| t | 9.85 | 4.26 | 17.24 | 6.91 | P = 0.14 | P = 0.14 | P = 0.73 | |

| P | ﹤0.001 | ﹤0.001 | ﹤0.001 | ﹤0.001 | ﹥0.05 | ﹥ 0.05 | ﹥0.05 |

(1) Recovery: Constipation and relevant symptoms disappeared. Auxiliary examinations showed that associated manifestations disappeared; (2) Improvement: Constipation and relevant symptoms were relieved. Auxiliary examinations showed that major relevant symptoms disappeared; (3) Inefficacy: Constipation and relevant symptoms were not obviously improved. Auxiliary examinations showed that constipation still existed.

According to the above criteria, twelve patients recovered (12/14, 85.7%) and two patients improved (2/14, 14.3%) in treatment group. In control group sixteen patients recovered (16/18, 88.9%) and two patients improved (2/18, 11.1%).

In treatment group, adhesive ileus occurred in one patient (relieved after expectant treatment later). Another patient developed grease liquefaction of incision. Acute pancreatitis occurred in one patient. Complication incidence was 21.4%. In control group, adhesive ileus occurred in three patients. The infection of incisional wound occurred in two patients. One patient developed adhesive stenosis of the ureter. Complication incidence was 33.3%. There were no death case, no postoperative stomal leak or anastomotic stricture in either groups.

All patients were followed for six to thirty-eight months. The follow-up rate was 100%. Most patients recovered very well after operations. Their constipation disappeared and the quality of their lives improved. One patient in treatment group still had abdominal distention. She was diagnosed as endometriosis later. And the indwelling colon was resected in another hospital. The other patients did not have any abdominal pain or abdominal distention. They evacuated their bowels one to three times every day. Their stools were almost forming. Three patients in control group still had slight abdominal distention. They evacuated their bowels one to four times every day. The shape of their stools was pasty.

Over the recent years in China, along with the improve-ment of the economy, quickening up of the life pace, change of the structure of foods and drinks, as well as aging of the population, the incidence of refractory constipation rises year by year. It has become one of the common diseases that affect the quality of people’s lives. Refractory constipation is usually classified into three types: slow transit constipation (STC), outlet obstructive constipation (OOC), mixed constipation (MC). Among them, mixed constipation is the most commonly seen in clinics.

The etiological factors of refractory constipation are very complicated and largely unclear; however, some of the etiological factors have been certain[2,3]. (1) Abnormalities in the enteric nervous system; (2) Abnormalities of extrinsic nerves; (3) Smooth muscle abnormalities; (4) Interstitial cell of Cajal dysfunction; (5) Structural abnormalities of the rectum and anus: such as rectal prolapse, rectocele, hemorrhoid; (6) Endocrine and metabolic conditions; (7) Drugs; (8) Psychogenic conditions. Understanding of the etiological factors will help us make correct treatment plans for the disease. Effective combined therapy can lead to better therapeutic efficacy.

Refractory constipation is not a fatal disease. We suggest expectant treatment for the constipated patients with a short course of disease and light pathogenetic condition. Constipated patients who have serious clinical symptoms, poor quality of life and a strong desire for surgery, however, should be considered to take colonic exclusion, except for the aged patients. According to our clinical observation and experience over the years, there are the following surgical indications for colonic exclusion: (1) Patients have serious difficult defecation for at least three years. The stool frequency is below three times every week. (2) Drug treatment for at least half a year is confirmed ineffective or patients have to ingest exceeding cathartics for a long time. (3) Gastrointestinal transit test shows that colonic transit becomes slower, while the stomach and small bowel transit are normal. Accompanying outlet obstructive diseases are confirmed by preoperative defecography. (4) Constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and constipations which are caused by drugs must be excluded. (5) The patient has no serious mental disorder and she (he) has a strong desire for operation. Surgeons should be cautious of surgical treatment for refractory constipation and handle surgical indications strictly. Patients should undergo preoperative psychological tests and clinical examinations of colorectal function. After that, individualized therapeutic strategies and surgical schema are made.

The phenomenon of slow colonic transit more or less exists in patients with refractory constipation. We used gastrointestinal transit test to detect gastrointestinal function of 14 patients in treatment group before operation. Forty-eight hours later the photographs showed that baric markers were still stagnated in transverse colon or sigmoid colon in 12 patients. Seventy-two hours later the photographs displayed retention of baric markers in sigmoid colon or rectum in nine patients. Bassotti et al[4] studied colonic propulsive activity in constipated patients and found colonic dysfunction. Both colonic contraction amplitude and high-amplitude propagated contractions were significantly decreased, which might be the immediate cause of colonic inertia. We examined nine patients in treatment group with barium enema after colon exclusion a month later. The intestine did not inflate and the anastomotic stoma transmitted normally (Figure 2). Three patients had barium reflux into the indwelling colon, but it was evacuated completely 24 h later (Figure 3). Hereby it demonstrated that the indwelling colon still had itself movement. It did not lose its peristalsis under the condition of disuse. However, it is uncertain whether it has any practical clinical significance to lay the colon with neuromuscular diseases in the abdominal cavity. By now, there is no definite conclusion about the long-term influence of the indwelling colon on human bodies.

Arbuthnot first adopted total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis to treat slow transit constipation in 1908. Afterwards people gradually adopted total colectomy with caecorectal anastomosis. These surgical methods could relieve constipation symptoms in most patients with chronic idiopathic constipation; however, they were associated with a considerable morbidity and were less effective in resolving symptoms of abdominal pain and bloating[5]. Based on the result of gastrointestinal transit test, people adopted hemicolectomy to treat constipated patients. They only resected some segmental long-winded colon. Hemicolectomy could lead to fewer postoperative complications and a faster recovery[6], but the postoperative recurrence rate was very high[7]. This is because the excisional range of the pathological colon is not large enough. After operation the residual colon transmits slower, which will lead to recurrence of constipation. On the other hand, subtotal colectomy is a popular operation to treat refractory constipation. It seldom leads to serious diarrhea for the remaining of ileocecal valve. However, it still has some disadvantages, such as big trauma, long surgical time, delayed recovery, many complications. Besides, patients’ postoperative quality of life is not so ideal[8]. We adopted colonic exclusion with colorectal anastomosis and neoplasty for symptomatic rectocele to treat constipated patients. The clinical results were satisfactory. Patients recovered excellently after operations. And there were no serious postoperative complications among them. Compared with the control group, it had smaller incision, fewer blood losses, shorter operational time and shorter hospital stay.

In conclusion, colonic exclusion has such advantages as: (1) less trauma, fast recovery; (2) simplified operation, shorter surgical process; (3) preservation of some bowels with normal function; (4) higher clinical cure rate; (5) avoidance of serious postoperative complications. For most constipated patients, colonic exclusion is the best surgical method because it is convenient, economical, less trauma, and less painful. It is especially indicated for aged constipated patients whose surgical endurances are not so good. We assume that it has wide application value.

The incidence of refractory constipation is very high in modern people, especially in aged people and middle-aged females. Some constipated patients have to be treated by surgery, while conventional surgical methods have big trauma. We recommend a new surgical method to treat refractory constipation. It is convenient, economical, less trauma, and less painful.

Surgical methods to treat refractory constipation are improving. Recently people pay more attention to microinvasive operation. Laparoscopic operations instead of conventional surgical methods are used to treat refractory constipation.

Colonic exclusion is a technical innovation in treating refractory constipation. Compared with conventional surgical methods, it doesn’t need to sever or resect too much colon and it retains some bowels with normal function. Rectocele is restored and the basement of pelvic cavity is reestablished. Therefore, it has less trauma and patients recover faster after operation.

Colonic exclusion has better therapeutic efficacy for refractory constipation. It has many advantages such as smaller incision, fewer blood losses, less adhesive ileus, shorter surgical time and shorter hospital stay. It is especially indicated for aged constipated patients, whose surgical endurances are not so good. It has wide application prospect in clinical practice.

Colonic exclusion: It is a surgical method that needn’t to resect the colon. The ascending colon is transected. Then the distal colon is closed and the proximal colon is end-to-side anastomosed with the rectum. An indwelling colon is laid in the abdominal cavity.

| 1. | Pfeifer J, Agachan F, Wexner SD. Surgery for constipation: a review. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:444-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Knowles CH, Martin JE. Slow transit constipation: a model of human gut dysmotility. Review of possible aetiologies. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2000;12:181-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Arce DA, Ermocilla CA, Costa H. Evaluation of constipation. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:2283-2290. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bassotti G, Chistolini F, Marinozzi G, Morelli A. Abnormal colonic propagated activity in patients with slow transit constipation and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2003;68:178-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Platell C, Scache D, Mumme G, Stitz R. A long-term follow-up of patients undergoing colectomy for chronic idiopathic constipation. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66:525-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lundin E, Karlbom U, Påhlman L, Graf W. Outcome of segmental colonic resection for slow-transit constipation. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1270-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ding SZ. A review and analysis of therapeutic effect about colectomy to treat slow transit constipation. Dachang Gangmen Zazhi. 2001;7:32-33. |

| 8. | FitzHarris GP, Garcia-Aguilar J, Parker SC, Bullard KM, Madoff RD, Goldberg SM, Lowry A. Quality of life after subtotal colectomy for slow-transit constipation: both quality and quantity count. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:433-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Liu WF