MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical data

Twenty-two patients with suspected massive small intestinal bleeding (13 males and 9 females) were included in the present study. Their age ranged from 16 to 61 years with a mean age of 38.6 years. The course of the disease ranged from 20 d to 10 years with a mean of 36.6 mo. The patients had recurrent massive bleeding, ranging from 3 to 15 times prior to admission with a mean of 5 times. The chief complaints were bright red or catsup-like bloody stools with concurrent abdominal pain in 4 cases. On the day of admission, the amount of bleeding was more than 1200 mL with concurrent hemodynamic changes. Hemoglobin ranged from 40.6 g/L to 66 g/L with a mean of 50.6 g/L. Massive small intestinal bleeding was suspected after bleeding from gastric duodenum, colon and rectum was excluded. Double contrast of barium and air examination of the alimentary tract were performed in 6 patients, of them 1 had small intestinal tumor and 1 had Meckel’s diverticulum. Small intestine enteroscopy was carried out in 5 patients, of them 2 had small intestinal bleeding due to Mechel’s diverticulum and 1 had small intestinal stromal tumor (Figures 1A and B). Emission CT scanning (ECT) of the abdominal cavity was performed in 6 patients, of them 2 had a small intestinal bleeding due to Mechel’s diverticulum and small intestinal tumor (Figure 2). Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was conducted in 3 patients, of them 1 had a jejunum tumor and 1 had the contrast medium in blood vessels of terminal ileum flowing into the intestinal cavity where pathological changes were not defined.

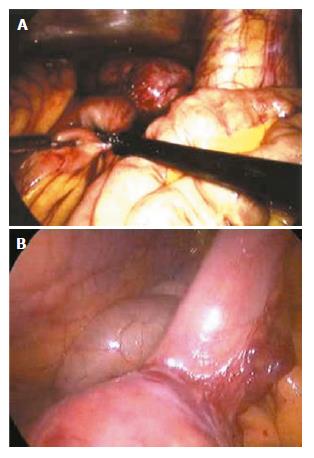

Figure 1 Laparoscopic laparotomy showing small intestinal bleeding (A and B).

Figure 2 An oval stromal tumor causing small intestinal bleeding.

Laparoscopic laparotomy found there is an oval stromal tumor on the up segment of jejunum, with clear borderline and smooth surface, having no adhesion with other tissue around it. Expansive abdominal excision was performed to draw out the tumor for resection.

Surgical procedures

Before operation, shock was treated with blood transfusion until hemoglobin level reached 90 g/L or above. After the blood pressure became normal, emergency laparoscopic laparotomy was performed under general anesthesia with the patients at a head-down position. A transverse incision (1 cm) was made 0.5 cm inferior to the umbilicus to establish pneumoperitoneum with a pressure of 13 mmHg. A hole was made inferior to the umbilicus to insert the laparoscope of 10 mm at 30°C to examine the abdominal viscera. Under the guidance of a laparoscope, a second and third holes of 5 mm were made at the level of umbilicus on the midlines of right and left clavicles. The second hole was used to check the whole small intestine from the part of the ileum and cecum to Treitz's ligament with a non-impairing laparoscopic bowel clamp, during which the proximal segment of intestinal tract from the boundary of the hematocele was observed and accumulated blood was squeezed out. The recurrent hematocele showed the definite bleeding site. When failing to reach the bleeding site, two alternative methods were used: perioperative small intestine enteroscopy to check the transparency of the intestinal wall with the help of a light source at the top of the enteroscope to localize the bleeding site, thus the small intestine near the hematocele was clamped out of the abdominal wall for incision and perioperative enteroscopy (Figure 3). After the bleeding site was localized, the third hole was dilated to make a 5 cm incision through the left rectus abdominis muscle to clamp the diseased intestinal segment, followed by resection of the diseased intestinal tract according to the laparotomy procedures (Figures 4A and B). In some cases, removal of the diseased small intestine and enteroanastomosis were performed under a laparoscope by transverse dilation of the hole inferior to the the umbilicus.

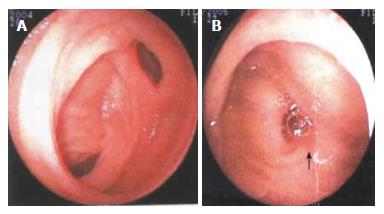

Figure 3 Electric intestinal endoscopy showing a benign jejunum tumor.

A deep ulcer sunken on the top of the tumor could be seen.

Figure 4 Double balloon enteroscopy showing the clamped diseased intestinal segment (A) and resected diseased intestinal tract (B).

The double-balloon enteroscope was pushed 200 cm into the ileum through anus. Diverticulum was found in the ileum 90-100 cm away from the ileocecal valve, at the opening of which a 1.2 cm × 1.0 cm ulcer was observed. The ulcer had thin covering of lichenoid substance, but no active bleeding. No other abnormalities were found. Meckel’s diverticulum was diagnosed.

RESULTS

The bleeding sites in these 22 patients were successfully found, of them 2 received laparoscopy combined with perioperative enteroscopy, 4 underwent perioperative incision of the small intestinal tract under laparoscope combined with perioperative enteroscopy under laparoscope. Massive small intestinal bleeding was caused by benign jejunum stromal tumor in 8 cases, by potential jejunum malignant stromal tumor in 5 cases, by malignant jejunum stromal tumor in 1 case, by Mechel’s diverticulum in 5 cases, by small intestinal vascular deformity in 2 cases with 1 case having 2 sites of jejunum vascular dysplasia with concurrent intestinal mucous ulcer (the two sites were 10 cm and 40 cm from Treitz’s ligament respectively) and by ectopic pancreas in 1 case. A total of 16 patients underwent laparoscopy-assisted enterectomy and enteroanastomosis of small intestine covering the diseased segment and 6 patients received enterectomy to remove the diseased segment under laparoscope. The operative duration ranged from 45 min to 180 min with a mean of 90 min. After operation, all patients recovered passing flatus through the anus and taking food within 2 d. No surgical complications occurred and the mean postoperative hospitalization time was 6.5 d. Phone call follow-up was conducted for 2-24 mo with no recurrent alimentary tract bleeding. The surgical outcome was satisfactory.

DISCUSSION

The small intestine is about 3-5 m long, occupying three fourths of the whole gastrointestinal tract. The ansa intestinalis is circuitous overlapping active peristalsis and its location varies greatly in the abdominal cavity. Since massive small intestinal bleeding lacks specific clinical symptoms and signs, it is difficult to diagnose and locate it by routine examinations[4-6]. Small intestine enteroscopy is the most specific method for its diagnosis but its application is limited because this examination is time-consuming, extremely unpleasant, and causes bleeding and perforation with a high false positive rate[7-13]. Recently, a capsule endoscope is under clinic experiment, but it cannot perform biopsy and make pathological diagnosis[10-13]. Stromal tumor is the most frequent cause of small intestinal bleeding[1-3,5], Mechel’s diverticulum and vascular conditions are the second frequent cause of small intestinal bleeding[1,4,6]. False positive tumor may not be shown on X-ray imaging of the whole alimentary tract because the bleeding foci often grows in exogenesis[14,15]. During the active stage of small intestinal bleeding, DSA can find the contrast medium flowing from the tumor site into the intestinal tract, showing local shadow with a slightly high density and embolism treatment can be conducted during diagnosis[15]. 99mTc-sestamibi is sensitive to mild intestinal bleeding , thus marking erythrocytes for gastrointestinal bleeding imaging, while it has no diagnostic value in the resting phase of bleeding or the bleeding being less than 0.05 mL/min[16]. At present, the diagnosis of massive obscure gastro-intestinal bleeding is usually made by exposure laparotomy, which is invasive with a false positive rate of 5%. Besides, patients with massive small intestinal bleeding are often weak with poor conditions and unstable vital signs, which prevent them from undergoing a major surgical operation.

Laparoscopy can clearly, directly and conveniently observe the whole intestinal serosa and mesentery and the small intestinal conditions can be managed with its assistance[11,16-20]. From December 2002, we have tried to use laparoscopy to manage obscure gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with massive small intestinal bleeding. The outcomes showed that laparoscopy could find the bleeding site of massive obscure gastro-intestinal bleeding. It is noninvasive with less pain and short recovery time. We believe that laparoscopy has a promising prospect in diagnosis and treatment of acute massive small intestinal bleeding and can be used as a routine method for the management of massive small intestinal bleeding[11,16,18,20]. Since intestinal stromal tumor and ectopic pancreas that cause small intestinal bleeding are generally small, examination followed by laparotomy cannot find the bleeding foci. Perioperative small intestine enteroscopy in combination with removal of hematocele can avoid the disadvantages of enteroscopy, such as time-consuming, extreme unpleasantness and complications of bleeding and perforation. Laparoscopy can find the bleeding foci, showing the advantages of noninvasive surgery. For those whose bleeding site is not defined by laparoscopy, perioperative enteroscopy of small intestine generally can reach the definite bleeding foci, deserving wide promotion[11,17,19,20].

In the present study, small intestinal bleeding occurred, leading to insufficient blood volume, the average hemoglobin level was 50.6 g/L. Once laparoscopy is accepted by patients, the laparoscope equipment and surgical appliances should be prepared as fast as possible for immediate surgery when shock takes a favorable return. The patient should lie on his/her left side at the head-down position. Firstly, parenchymatous viscera should be generally examined, followed by examination of the whole small intestine. This part of the ileum and cecum has a relatively stable location in the abdominal cavity and thus is easily exposed. Cecum should be used as the landmark during laparoscopic exploration, which starts from the terminal ileum with each 10 cm as one segment to the Treize’s ligament. One patient had 2 sites with small intestinal vascular deformity so that exploration of the whole small intestine segment by segment was emphasized to avoid missing any focus. The laparoscopic exploration of small intestinal hemangiomas or vascular deformity should be more careful. The intestinal wall should be carefully explored for local prominence, pitting, overlapping and abnormal mesentery. The suspected bleeding segment should be palpated carefully with clamps to feel its hardness, flexibility, and activity. In case of active massive bleeding, intestinal peristalsis is active and the blood often accumulates in the distal bleeding segment which is dark blue under laparoscope. The suspected foci can be confirmed if emptied, blocked and reformed hematocele is found. The time-consuming examination is mainly due to repeated enteroscopy. One patient with a history of 3-year bleeding had no positive laparoscopic findings. Repeated examinations had no other positive findings. A slightly hard intestinal wall of this part was touched during exploration, which was ectopic pancreas confirmed by pathological biopsy.

After the bleeding site was found by laparoscopy, laparoscopy-assisted enterectomy and enteroanastomosis were performed, during which an exploratory incision about 5 cm in length was made at the umbilicus level on the midline of the left clavicle to remove the diseased intestinal segment. The resected part of the small intestine should be 5 cm longer than the bleeding site that may result in a fast and reliable excision with light contaminations in the abdominal cavity. Enterectomy and enteroanastomosis can be performed under laparoscope in those whose bleeding sites are adjacent to the Treize’s ligament, thus the diseased segment can be conveniently removed[1,2,11,16-20].

In conclusion, laparoscopy in diagnosis and treatment of massive small intestinal bleeding is noninvasive with less pain, short recovery time and definite therapeutic efficacy and has rather good clinical application prospects.