Published online Nov 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i43.6992

Revised: September 25, 2006

Accepted: October 6, 2006

Published online: November 21, 2006

AIM: To evaluate whether the Milan criteria are useful in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who received transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) before liver transplantation (LT).

METHODS: Thirty-six HCC patients who fulfilled the Milan criteria after having received TACE and subsequently underwent LT were included (TACE + LT group) in the study. As controls, 21 patients who also met the Milan criteria and underwent LT without prior treatment were selected (LT group). Post-LT clinical outcomes, such as HCC recurrence, survival rate, and histologic features of explanted livers, were compared between the two groups.

RESULTS: Baseline characteristics were not different between the two groups. Pre-LT maximal tumor diameter in TACE + LT group was similar to that of LT group (2.0 ± 0.6 cm vs 2.3 ± 0.9 cm; P = 0.10). Post-LT histologic findings also revealed similar maximal tumor diameter in the two groups (2.4 ± 1.4 cm vs 2.3 ± 0.9 cm; P = 0.70). Explanted livers showed similar incidence of unfavorable pathologic features. The morality within 60 d after transplantation was not different between the two groups (8.3% vs 9.5%; P = 0.99). Post-LT 5-year survival rate (57% vs 74%; P = 0.70) and cumulative recurrence rate (8.3% vs 4.8%; P = 0.90) were not significantly different between the two groups.

CONCLUSION: The Milan criteria are still a useful selec-tion criteria showing favorable outcomes in HCC patients receiving TACE before LT.

- Citation: Kim DY, Choi MS, Lee JH, Koh KC, Paik SW, Yoo BC, Shin SW, Choo SW, Do YS, Rhee JC. Milan criteria are useful predictors for favorable outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing liver transplantation after transarterial chemoembolization. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(43): 6992-6997

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i43/6992.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i43.6992

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a major global health problem involving more than 500 000 new cases a year. Several treatment modalities, such as liver transplantation (LT), surgical resection, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), are accepted for curative therapies for HCC. Theoretically, LT remains the only ideal treatment option because LT has been claimed to simultaneously cure the malignant disease and replace the premalignant cirrhotic liver. Early series of LT for HCC yielded poor outcomes[1-4]. In those series, 3- and 5-year survival after LT ranged 15%-67% and 15%-48%, respectively. These inferior results come from inclusion of patients with far advanced HCC. In spite of initial dismal experiences with LT for patients with HCC, patients with confined HCC (solitary lesion ≤ 5 cm or ≤ 3 lesions with diameter ≤ 3 cm, no major vessel invasion, and no extrahepatic involvement; Milan criteria) were reported to show an excellent long-term outcome with a 5-year survival rate of 70% and a recurrence rate below 15%[5]. With pathologic review, modestly expanded selection criteria (solitary lesion ≤ 6.5 cm or ≤ 3 lesions with the largest one ≤ 4.5 cm and total tumor diameter ≤ 8 cm; UCSF criteria) were suggested to offer an excellent outcomes with a 1- and 5-year survival rate of 90% and 75.2%, respectively[6]. In clinical practice, however, the Milan criteria based on pre-LT radiologic findings could be more useful and a widely accepted selection criteria than the UCSF criteria based on post-LT pathologic findings.

Because of donor organ shortage or other limits including economic problem in HCC patients waiting for LT, various treatment modalities including resection, RFA, PEI, and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) were tried to prevent the progression of HCC. Among these, TACE is the most commonly used procedure in patients with unresectable HCC in our country. Up to now, it is not known whether a favorable outcome after LT can also be achieved in HCC patients who have been treated by TACE and meet the Milan criteria, as in treatment-naïve HCC patients.

Hence, we conducted a study to assess the usefulness of the Milan criteria in HCC patients who had been treated with TACE prior to LT.

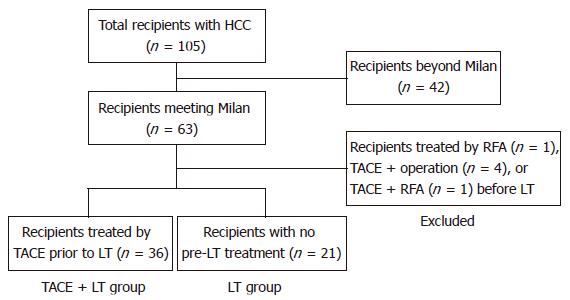

Between September 1996 and April 2004, a total of 105 patients with HCC underwent LT at our institute. Among them, 63 (59.4%) patients met the Milan criteria based on pre-LT imaging. Excluding 27 patients within Milan criteria treated by RFA or surgical resection before LT, 36 patients with one or more sessions of TACE only prior to LT were selected (TACE + LT group). Twenty-one HCC patients who had not been given any treatment before LT were selected as control (LT group) (Figure 1). The Milan criteria was defined as the presence of a tumor 5 cm or less in diameter in patients with single HCC or no more than 3 tumor nodules, each 3 cm or less in diameter, in patients with multiple tumors, and no extrahepatic metastasis, and no major hepatic vessel invasion[5].

One to eight sessions of TACE were performed via the transfemoral arterial approach under local anesthesia at intervals of 4-12 wk in the TACE + LT group. Selective celiac and superior mesenteric angiography was performed to define the hepatic artery anatomy and to evaluate the portal venous system. The feeding artery to the lesion was catheterized as selectively as possible using a highly flexible coaxial catheter, and the chemotherapeutic agent lipiodol mixture was injected under fluoroscopic guidance. The mixture contained 20-50 mg of doxorubicin, 3-20 mL of lipiodol (Lipiodol Ultrafluide; Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bis, France), and 3 mL of water-soluble contrast agent. Embolization was performed with gelatin pellets (Gelfoam; Upjohn, Kalamazoo, Michigan) thereafter in patients with liver function of Child-Pugh class A and tumor confined to single lobe of the liver. This Gelfoam embolization was also performed for patients with Child-Pugh B, if superselection of the feeding vessel was feasible. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan was performed 4 wk after TACE to evaluate the anti-tumor effect of TACE, including lipiodol uptake by the tumor tissue. If viable tumor was still observed in CT, repeated TACE was performed. If lipiodol was compactly uptaken by all tumor nodules and any new lesion was not seen, follow-up CT scan was repeated every 3 mo.

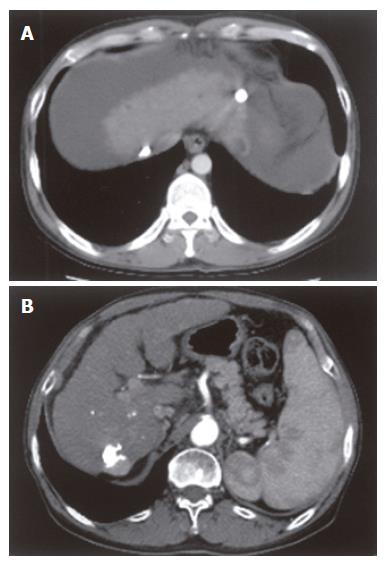

As for tumor size in the LT group, any nodular lesion showing arterial enhancement and delayed washout in 3-phase helical CT was regarded as a viable HCC and its largest diameter was considered as a tumor size. In the TACE + LT group, a tumor nodule showing compact lipiodol uptake without arterial enhancement or delayed washout in CT was considered as non-viable tumor and was excluded from the measurement of tumor size or number. For a nodule showing arterial enhancement and delayed washout at the margin, tumor size was defined as the difference from diameter of the entire nodule to diameter of lipiodol-uptaken portion. Representative cases showing how to measure the HCC lesions treated by TACE are illustrated in Figure 2.

All total hepatectomy specimens were processed by a hepatopathologist using a routine protocol consisting of 1 cm or thinner sections throughout the entire liver. With standard histological staining, the specimens were examined to evaluate tumor characteristics, such as number of nodules, size, pathologic tumor grade (Edmonson grade), percentage of necrosis, and presence of tumor capsule invasion, satellite nodule, or microvascular invasion. By pathologic review of explanted liver, it was evaluated whether the enrolled patients also met the UCSF criteria.

Post-transplant immunosuppression consisted of corticosteroid plus either tacrolimus or cyclosporin. Corticosteroid was gradually tapered and was discontinued within 1 year. Tacrolimus and cyclosporin were continued after LT unless contraindicated. Acute rejection was treated with steroid pulse therapy. Antithymocyte globulin (ATG) or muromonab (OKT3) antibody infusions were reserved for the patients with acute rejection resistant to intravenous corticosteroids. The interval of the outpatient clinic visits after discharge from the hospital was adjusted according to the patient’s condition.

Tumor recurrence was screened by measurement of alpha-fetoprotein and abdominal CT or ultrasonography every 3 mo. Additional imaging modalities, such as chest CT and bone scan, were performed if HCC recurrence at lung or bone was suspected. No adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to any patients after LT.

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the medical records, radiologic and pathologic findings of the 36 patients in TACE + LT group and 21 in the LT group. Baseline clinical characteristics of the patients, tumor characteristics, clinical outcomes including recurrence of HCC, and post-LT survival rate were compared between the two groups.

Baseline characteristics of the patients were expressed as mean ± SD. Comparison between the two groups was done by using the independent t test for continuous variables and by chi-square test or Mann-Whitney U test for categorical variables. The overall survival rate and cumulative recurrence rate were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The survival curves were compared by means of the log-rank test. All statistical tests were two-tailed and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

A total of 57 patients (49 men and 8 women; median age 51 years, range 30-68 years) were included in this study. Fifty-three patients (93.0%) had HCC associated with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Other causes consisted of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in 2 patients (3.5%), co-infection of HBV/HCV in one (1.8%), and alcohol-related liver disease in one (1.8%). The mean alpha-fetoprotein levels were 494.9 μg/L and model for end stage liver disease (MELD) score was 19.4. One to eight sessions of TACE were performed in TACE + LT group; 1 session in 12 (33.3%) patients, 2 sessions in 16 (44.4%) patients, and 3 or more sessions in 8 (22.2%) patients. Cadaveric grafts were used in 10 (17.5%) and living grafts in 47 (82.5%) cases. As for baseline clinical and demographic characteristics, there was no significant difference between TACE + LT group and LT group (Table 1).

According to pre-LT radiologic evaluation, 42 (73.7%) patients had single tumor, and 8 (14.0%) and 7 (12.3%) patients had 2 and 3 tumors, respectively. The mean diameter of the largest nodule in all patients was 2.1 cm. In TACE + LT group, 24 (66.7%) patients had single tumor, 6 (16.7%) patients had 2 tumors, and 6 (16.7%) patients had 3 tumors. The distribution of tumor number was similar in the LT group; 1 in 18 (85.7%) patients, 2 in 2 (9.5%) patients, and 3 in 1 (9.5%) patient. No statistical difference was found in the mean diameter of the largest tumor between TACE + LT and LT groups (2.0 cm vs 2.3 cm; P = 0.10; Table 1).

| Characteristics | TACE + LT group (n = 36) | LT group (n = 21) | P |

| Age (yr) | 49 ± 8.2 | 52 ± 8.0 | 0.13 |

| Sex (M/F) | 31/5 | 18/3 | 0.99 |

| Etiology of liver disease | 0.12 | ||

| HBV | 34 (94.4%) | 18 (85.7%) | |

| HCV | 0 (0%) | 2 (9.5%) | |

| HBV + HCV | 1 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Alcoholic | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.8%) | |

| α-fetoprotein (µg/L) | 193 ± 472 | 1012 ± 4110 | 0.24 |

| TACE | |||

| 1 | 12 (33.3%) | - | |

| 2 | 16 (44.4%) | - | |

| ≥ 3 | 8 (22.2%) | - | |

| MELD score | 19 ± 9 | 22 ± 9 | 0.10 |

| Type of graft | |||

| Cadaveric graft | 8 (22.2%) | 2 (9.5%) | 0.30 |

| Living graft | 28 (77.8%) | 19 (90.5%) | |

| Number of nodules | |||

| 1/2/3 | 24/6/6 | 18/2/1 | 0.26 |

| Diameter of the largest tumor (cm) | 0.10 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | |

| Range | 0.9-4.0 | 1.0-4.0 | |

| Sum of the tumor diameters (cm) | 0.38 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 2.8 ± 1.3 | |

| Range (cm) | 0.9-6.1 | 1.0-5.9 | |

According to histopathologic findings of explanted livers, a total of 114 nodules were found from all the patients; 77 in the TACE + LT group and 37 in the LT group. The number of tumor nodule was 1 in 31 (54.4%) patients, 2 in 8 (14.0%) patients, 3 in 3 (5.3%) patients, and 4 or more in 15 (26.3%) patients. The mean diameter of the largest tumor was 2.4 cm and the sum of the tumor diameters was 3.6 cm. There was no significant difference in distribution of tumor number between the two groups. The mean diameter of the largest tumor and the sum of the tumor diameters were also similar between both groups (2.4 cm vs 2.3 cm, P = 0.70; 3.8 cm vs 3.3 cm, P = 0.36, respectively, Table 2). Twenty-eight (77.8%) patients in the TACE + LT group and 19 (90.5%) in the LT group met the UCSF criteria.

| Variable | TACE + LT group (n = 36) | LT group (n = 21) | P |

| Number of nodules | |||

| 1/2/3/≥4 | 18/8/3/7 | 13/3/3/2 | 0.79 |

| Diameter of the largest tumor (cm) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 0.70 |

| Range | 0.6-7.5 | 0.5-4.2 | |

| Sum of the tumor diameters (cm) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 3.8 ± 2.6 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 0.36 |

| Range | 0.6-14.0 | 0.5-7.0 | |

| Tumor differentiation1 | 0.59 | ||

| Edmonson gradeI | 5 (16.7%) | 6 (28.6%) | |

| II | 22 (73.3%) | 13 (61.9%) | |

| III | 3 (10%) | 2 (9.5%) | |

| Presence of satellite nodule | 5 (13.9%) | 2 (9.5%) | 0.99 |

| Tumor capsule invasion | 11 (30.6%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0.21 |

| Microvascular invasion | 11 (30.6%) | 9 (42.9%) | 0.40 |

As to the tumor differentiation, Edmonson grade 1 was found in 11 (21.6%), grade 2 in 35 (68.6%), and grade 3 in 5 (9.8%) patients. Of 57 patients, 7 (12.3%) and 14 (28.8%) patients had satellite nodules and tumor capsule invasion, respectively. In addition, 20 (35.1%) patients had microvascular invasion. The incidence of unfavorable pathologic features was similar in the two groups (Table 2). The explanted liver showed TACE-induced complete tumor necrosis without histologic evidence of viable carcinoma in 23 of 77 (29.9%) lesions.

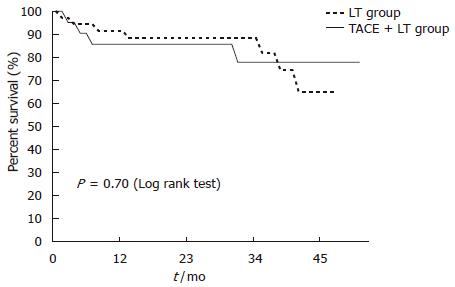

During median follow-up of 24.3 (range: 0.1-99) mo, 14 of 57 (24.6%) patients died. Post-LT early mortality, defined as death within 60 d after transplantation, was not different between TACE + LT and LT groups (8.3% vs 9.5%; P = 0.99). The overall survival rates of the patients at 1-, 3-, and 5-year were 86%, 72%, and 67%, respectively. The 1-, 3-, 5-year survival rates between the TACE + LT group and the LT group were not significantly different (89% vs 81%, 68% vs 74%, and 57% vs 74%, respectively; P = 0.70) (Figure 3). The causes of death consisted of graft failure in 3 patients, graft versus host disease (GVHD) in 2 cases, hepatic vein problem with hepatic congestion in 1 case, HBV recurrence in 3 cases, HCC recurrence in 4 cases, and intracerebral hemorrhage in 1 case.

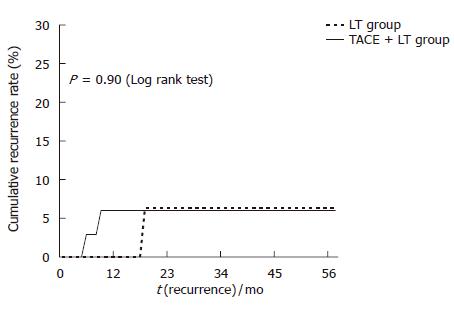

During the follow-up period, HCC recurrence was found in 4 (7.0%) patients (Table 3). Five-year cumulative HCC recurrence rate in the TACE + LT group was similar to that in the LT group (8.3% vs 4.8%; P = 0.90) (Figure 4).

| Patient | Group | Time to recur (mo) | Site of recur | Treatment after recurrence | Survival (mo) |

| 1 | TACE + LT | 9.6 | Liver | None | 10.0 |

| 2 | TACE + LT | 3.3 | Liver, bone | TACE | 7.1 |

| 3 | LT | 15.4 | Lymph node | Excision, TACE | 21.0 |

| 4 | TACE + LT | 0.9 | Lung, liver | TACE | 5.7 |

HCC is one of the serious complications of chronic liver disease associated with high mortality. Although surgical resection is traditionally regarded as treatment of choice for HCC, it is a major problem that resection is feasible in only limited cases due to poor liver function and/or advanced stage of HCC at diagnosis. In addition, many patients suffer from recurrent HCC and aggravation of cirrhosis after operation. In this regard, LT gives patients with HCC an advantage over resection, because it addresses the multifocal potential of HCC in many patients that limits the success and applicability of resection and also treats the underlying liver disease[6].

The criteria developed by Mazzaferro and associates, known as the Milan criteria, have been widely applied around the world in the selection of patients with HCC for LT. However, the Milan criteria were originally made for patients with treatment-naïve HCC. In the clinical setting, a significant number of HCC patients are treated with TACE or RFA prior to LT because of a long waiting list for LT. It remains uncertain whether excellent outcomes can be obtained in HCC patients who previously underwent locoregional treatments and still meet the Milan criteria at the time of LT. In the present study, we retrospectively selected the patients who had received only TACE before they underwent LT since TACE is the most widely used procedure for HCC in our country. Patients undergoing other therapies, such as resection or RFA, were excluded to eliminate confounding effect of those treatments. For validation of usefulness of the Milan criteria in HCC patients treated with TACE before LT, their survival rates following LT were compared with those of HCC patients undergoing LT only.

The current study demonstrates that HCC patients who had undergone one or more sessions of prior TACE showed as good post-LT survival as treatment-naïve HCC patients, if they met the Milan criteria at the time of transplantation. One- and 5-year survival rates of patients in the TACE + LT group and LT group were comparable (89% vs 81% and 57% vs 74%, respectively; P = 0.70). Taniguchi et al[7] showed a long-term survival and marked TACE-induced tumor necrosis in patients with unresectable HCC. A recent report on randomized controlled trial showed that TACE with doxorubicin and gelatin sponge, compared with conservative management, provided survival benefits to patients with unresectable HCC[8]. However, as a bridge to transplantation for patients on waiting lists, TACE showed varying results[9,10]. Among these, an European study showed a 5-year survival of 93% in 48 patients receiving TACE, with no dropout over a mean waiting period of 6 mo[10]. Moreover, prospective studies have shown that the probability of preventing tumor progression is significantly higher in patients treated with TACE than those untreated controls[11,12]. In a recent series, pre-LT TACE in 54 predominantly early-stage cases yielded a reasonable 5-year post-LT survival of 74%[13]. However, the benefit of TACE could not be inferred given that waiting list dropout and post-LT recurrence rates were not markedly lower than historical controls. In contrast to previous studies regarding the role of TACE before LT, we elucidated the usefulness of the Milan criteria at the time of LT in patients receiving TACE prior to LT.

Up to now, there is no data on whether pre-LT TACE increases early mortality after transplantation compared to LT without prior therapy. In a previous study, some patients who underwent LT within 30 d of the last TACE developed unexplained severe pneumonia, leading to death very early after transplantation[9]. On the other hand, our results showed that mortality within 60 d after transplantation was not different between TACE + LT and the LT groups. Thus, the issue concerning pre-LT TACE and early mortality after operation still remains controversial.

In our study, 1-year survival rates of LT group were lower than those of TACE + LT group, albeit not statistically significant (89% vs 81%). Although the reason for this observation is not clearly understood, it might be due to the poorer liver function of patients in LT group as compared with the TACE + LT group. Urgent transplantations might have been undertaken in patients of the LT group whose liver functions were too poor to perform locoregional therapy. The tendency of higher MELD score (22 vs 19; P = 0.10) and more frequent living donor transplantation in the LT group compared to the TACE + LT group (90.5% vs 77.8%; P = 0.30) support the more aggravated liver function and urgent condition of the LT group.

Our data demonstrated that 5-year cumulative recurrence rates of patients in the TACE + LT group were similar to those in the LT group (8.3% vs 4.8%; P = 0.90). HCC recurred in 3 of 36 patients in the TACE + LT group with a recurrence site of liver in one and distant organs in two patients. In the LT group, the recurrence occurred in one patient at the perihepatic lymph node. Increased incidence of hepatic or extrahepatic recurrence after TACE followed by resection has been an important concern on the grounds that partial necrosis of the tumor favors the shedding of neoplastic cells in a few previous studies[14-17]. However, such a concern was not substantiated in our patients.

There was no significant difference between the TACE + LT group and the LT group in terms of baseline clinical and demographic characteristics, radiologic finding-based or histologic finding-based tumor profiles, and histologic parameters indicating unfavorable prognosis. At this point, we have to comment on the radiologic measurement of HCC lesions previously treated with TACE. In the TACE + LT group, albeit statistically not significant, the radiologically measured diameter of the largest tumor was shorter than the histologically measured one (2.0 ± 0.6 cm vs 2.5 ± 1.4 cm; P = 0.06), and 4 of 36 patients in the TACE + LT group were found to have 4 or more nodules on explanted specimens. In the LT group, the radiologically measured diameter of the largest tumor was similar with the histologically measured one (2.3 ± 0.9 cm for both), and 2 of 21 patients in the LT group had 4 or more nodules on explanted livers. These results imply that pre-LT staging of HCC by the current imaging modalities may be underestimated in terms of number in both groups and in terms of size in the TACE + LT group.

Although the extents of HCCs were estimated by expert radiologists using a pre-defined method, it was difficult to precisely measure the maximal diameter of lesions in a portion of the TACE + LT group, especially in cases with incomplete or scattered lipiodol uptake in nodules. In a previous study measuring the tumor volume (TV) to improve the selection criteria based on number and diameter of HCC, TV > 28 cm3 was reported to be a predictive factor for HCC recurrence after LT[18]. Other investigators measuring the TV with a region-of-interest CT technique also evaluated the prognostic value of volumetric CT in patients treated with repeated TACE[19]. These alternative methods might better represent the tumor size, but are much more complex and time-consuming.

In conclusion, our data demonstrated that the Milan criteria would be useful selection criteria in HCC patients who underwent the TACE procedure before LT, showing favorable prognosis if they fulfill the criteria at the time of transplantation.

| 1. | Ringe B, Pichlmayr R, Wittekind C, Tusch G. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: experience with liver resection and transplantation in 198 patients. World J Surg. 1991;15:270-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE, Sheahan DG, Yokoyama I, Demetris AJ, Todo S, Tzakis AG, Van Thiel DH, Carr B, Selby R. Hepatic resection versus transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1991;214:221-228; discussion 228-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Moreno P, Jaurrieta E, Figueras J, Benasco C, Rafecas A, Fabregat J, Torras J, Casanovas T, Casais L. Orthotopic liver transplantation: treatment of choice in cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:2296-2298. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bismuth H, Chiche L, Adam R, Castaing D, Diamond T, Dennison A. Liver resection versus transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Ann Surg. 1993;218:145-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 650] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5110] [Cited by in RCA: 5398] [Article Influence: 179.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 6. | Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33:1394-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1594] [Cited by in RCA: 1721] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Taniguchi K, Nakata K, Kato Y, Sato Y, Hamasaki K, Tsuruta S, Nagataki S. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with transcatheter arterial embolization. Analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer. 1994;73:1341-1345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, Ayuso C, Sala M, Muchart J, Solà R. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734-1739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2502] [Cited by in RCA: 2655] [Article Influence: 110.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Oldhafer KJ, Chavan A, Frühauf NR, Flemming P, Schlitt HJ, Kubicka S, Nashan B, Weimann A, Raab R, Manns MP. Arterial chemoembolization before liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: marked tumor necrosis, but no survival benefit. J Hepatol. 1998;29:953-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Graziadei IW, Sandmueller H, Waldenberger P, Koenigsrainer A, Nachbaur K, Jaschke W, Margreiter R, Vogel W. Chemoembolization followed by liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma impedes tumor progression while on the waiting list and leads to excellent outcome. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:557-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | A comparison of lipiodol chemoembolization and conservative treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Groupe d'Etude et de Traitement du Carcinome Hépatocellulaire. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1256-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 629] [Cited by in RCA: 595] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Bruix J, Llovet JM, Castells A, Montañá X, Brú C, Ayuso MC, Vilana R, Rodés J. Transarterial embolization versus symptomatic treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a randomized, controlled trial in a single institution. Hepatology. 1998;27:1578-1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Maddala YK, Stadheim L, Andrews JC, Burgart LJ, Rosen CB, Kremers WK, Gores G. Drop-out rates of patients with hepatocellular cancer listed for liver transplantation: outcome with chemoembolization. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:449-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu CC, Ho YZ, Ho WL, Wu TC, Liu TJ, P'eng FK. Preoperative transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for resectable large hepatocellular carcinoma: a reappraisal. Br J Surg. 1995;82:122-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Adachi E, Matsumata T, Nishizaki T, Hashimoto H, Tsuneyoshi M, Sugimachi K. Effects of preoperative transcatheter hepatic arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. The relationship between postoperative course and tumor necrosis. Cancer. 1993;72:3593-3598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liou TC, Shih SC, Kao CR, Chou SY, Lin SC, Wang HY. Pulmonary metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with transarterial chemoembolization. J Hepatol. 1995;23:563-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Ravaioli M, Grazi GL, Ercolani G, Fiorentino M, Cescon M, Golfieri R, Trevisani F, Grigioni WF, Bolondi L, Pinna AD. Partial necrosis on hepatocellular carcinoma nodules facilitates tumor recurrence after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:1780-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ravaioli M, Ercolani G, Cescon M, Vetrone G, Voci C, Grigioni WF, D'Errico A, Ballardini G, Cavallari A, Grazi GL. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: further considerations on selection criteria. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1195-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vogl TJ, Trapp M, Schroeder H, Mack M, Schuster A, Schmitt J, Neuhaus P, Felix R. Transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: volumetric and morphologic CT criteria for assessment of prognosis and therapeutic success-results from a liver transplantation center. Radiology. 2000;214:349-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Wang GP L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Liu WF