Published online Oct 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i39.6371

Revised: May 28, 2006

Accepted: July 18, 2006

Published online: October 21, 2006

AIM: To assess the clinical features, yield of the diagnostic tests and outcome of abdominal tuberculosis in non-HIV patients.

METHODS: Adult patients with discharge diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis (based upon; positive microbiology, histo-pathology, imaging or response to trial of anti TB drugs) during the period 1999 to 2004 were analyzed. Patient’s characteristics, laboratory investigations, radiological, endoscopic and surgical findings were evaluated. Abdominal site involved (intestinal, peritoneal, visceral, and nodal) and response to treatment was also noted.

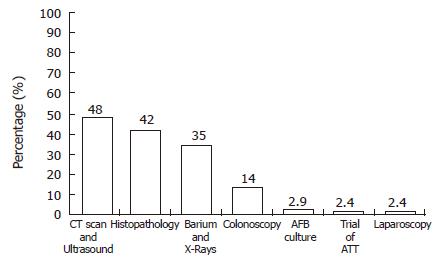

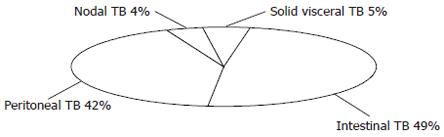

RESULTS: There were 209 patients enrolled. One hundred and twenty-three (59%) were females. Symptoms were abdominal pain 194 (93%), fever 134 (64%), night sweats 99 (48%), weight loss 98 (47%), vomiting 75 (36%), ascites 74 (35%), constipation 64 (31%), and diarrhea 25 (12%). Sub-acute and acute intestinal obstruction was seen in 28 (13%) and 12 (11%) respectively. Radiological evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis was found in 134 (64%) patients. Basis of diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis were radiology (Chest and barium X-Rays, Ultrasound and CT scan abdomen) in 111 (53%) and histo-pathology (tissue obtained during surgery, colonoscopy, CT or ultrasound guided biopsy, laparoscopy and upper gastro intestinal endoscopy) in 87 (42%) patients. Mycobacterium culture was positive in 6/87 (7%) patients and response to therapeutic trial of anti tubercular drugs was the basis of diagnosis in 5 (2.3%) patients. Predominant site of involvement by abdominal TB was intestinal in 103 (49%) patients, peritoneal in 87 (42%) patients, solid viscera in 10 (5%) and nodal in 9 (4%) patients. Response to medical treatment was found in 158 (76%) patients and additionally 35 (17%) patients also underwent surgery. In a 425 ± 120 d follow-up period 12 patients died (eight post operative) and no case of relapse was noted.

CONCLUSION: Abdominal TB has diverse and non- specific symptomatology. No single test is adequate for diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis in all patients. Abdominal TB in non-HIV patients remains an ongoing diagnostic dilemma requiring a high index of clinical suspicion.

- Citation: Khan R, Abid S, Jafri W, Abbas Z, Hameed K, Ahmad Z. Diagnostic dilemma of abdominal tuberculosis in non-HIV patients: An ongoing challenge for physicians. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(39): 6371-6375

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i39/6371.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i39.6371

In developing countries, tuberculosis is associated with poverty, deprivation, overcrowding, illiteracy, and limited access to health care facilities. While in developed worlds, tuberculosis is commonly accompanied with HIV infection, ageing population or due to trans-global migration[1,2]. Approximately one eighth of total TB cases are extra pulmonary[3,4], of these abdominal tuberculosis (ATB) accounts for 11%-16%[5,6]. In HIV positive patients the incidence of extra pulmonary TB is up to 50%[1,6].

TB involves the abdomen as the primary disease from the reactivation of a dormant focus acquired somewhere in the past or as a secondary disease when infections spread to the abdomen via swallowed sputum, hematogenous or spread from an infected neighboring organ or ingestion of unpasteurized milk[2,5]. Abdominal TB may be, enteric (intestine involved itself), peritoneal, nodal (lymph nodes involvement) and solid visceral TB like liver, spleen, kidney and pancreas or in any combination of these four varieties. Intestinal lesions may be ulcerating, hyperplastic or combined[7,8].

Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis is difficult because of (1) vague and non-specific clinical features or (2) low yield of mycobacterium culture or smear. Moreover, costly and invasive procedures are required for obtaining tissue for histo-pahtological examination or culture and these are not easily available in developing countries[6,9]. Investigations like Imaging (ultrasound, barium X-Rays, and CT scan) and Mantoux test have only supportive value. In some cases, response to therapeutic trials of anti-tuberculous drugs is the basis of diagnosis that may cause a delay in the diagnosis of other diseases which mimic abdominal tuberculosis e.g. Crohn’s disease, abdominal lymphoma and malignancy of abdominal organs[5]. Therefore, diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis is an ongoing challenge to the physicians, especially with limited resources.

The aims of this study were to examine the clinical features and distribution of the disease, diagnostic yield of various tests and outcomes of abdominal tuberculosis in non-HIV patients.

Patients above 15 years of age with a diagnosis of abdominal TB on discharge during the study period January 1999 to December 2004 were retrieved using the International classification of diseases 9th revision with clinical modification (ICD-9-CM- USA). Diagnosis of abdominal TB was based upon (1) a positive Acid Fast Bacilli (AFB) smear or culture, (2) histo-pathology showing tubercular granuloma (with or without caseation), (3) radiological features compatible with tuberculosis on barium x-rays of the abdomen, ultrasound or CT scan of the abdomen, and (4) patients with a high index of clinical suspicion and negative diagnostic workup but showed a good response to therapeutic trial of anti TB medicines[10].

Patient’s demographic, clinical features associated with medical illnesses, family and past history of TB were evaluated. Laboratory tests, mantoux skin test, chest and abdominal imaging results, histo-pathology findings, Acid Fast Bacilli (AFB) staining and culture reports, ascetic fluid analysis, HIV screening, findings of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, laparoscopy or laparatomy were noted. Response to anti-tubercular treatment surgical procedure performed, clinical course and complications were also evaluated.

The Statistical package for social science (SPSS 11.5) IL-Chicago- USA standard version was used for data analyses. Descriptive analysis was done for demographic, clinical and radiographic features and results are presented as mean ± SD and percentages for continuous variable and number and percentage for categorical variable. All P-values were two sided and considered as statistically significant if P < 0.05.

A total of 209 patients were analyzed and 123 (59%) were female. Mean age was 33 ± 15 years. The most frequent symptoms were abdominal pain (194, 93%), fever (134, 64%), night sweats (99, 48%), weight loss (98, 47%), vomiting (75, 36%), ascites (74, 35%), constipation (64, 31%), and diarrhea (25, 12%). Sub acute and acute intestinal obstruction was present in 28 patients (13%) and 22 (11%) patients, respectively (Table 1). Average duration of symptoms before first presentation was 265 ± 150 d. Past history of treatment for tuberculosis was present in 13 (6.2%) patients and a family history of tuberculosis was found in 6 patients (2.9%). Important systemic diseases associated with abdominal TB were diabetes mellitus in 22 (10.5%) patients and cirrhosis of liver 15 (7.7%).

| Patients characteristic | n | % |

| Male | 86 | 41 |

| Female | 123 | 59 |

| Past History of TB | 13 | 6 |

| Family History of TB | 6 | 3 |

| Associated Pulmonary TB | 10 | 5 |

| Abdominal pain | 194 | 93 |

| Fever | 134 | 64 |

| Night sweats | 99 | 48 |

| Weight loss | 98 | 47 |

| Vomiting | 75 | 36 |

| Ascites | 74 | 35 |

| Constipation | 64 | 31 |

| Diarrhea | 25 | 12 |

| Sub acute intestinal Obstruction | 28 | 13 |

| Acute intestinal Obstruction | 22 | 11 |

Radiology: Out of 209 patients, 130 were subjected to abdominal radiological investigations and presumptive diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis was made in 110 patients (53%) (Table 2) that included barium meal and follow through in 58/70 (83%), barium enema in 15/34 (44%), ultrasound in 72/93 (77%) and CT scan abdomen in 28/35 (80%). Common features suggestive of abdominal tuberculosis on barium X-Rays were luminal narrowing with proximal dilation of bowel loops in 52/58 (90%) patients. Whereas on abdominal ultrasound and CT scan, findings suggestive of abdominal tuberculosis were; ascites 87/110 (79%), enlarged lymph nodes in 39/110 (35%), omental thickening 32/110 (29%) and bowel wall thickness in 28/110 (25%) patients. Features suggestive of pulmonary tuberculosis on x-rays chest were found in 134 (64%) patients and 10 (4.8%) patients had radiological features of active pulmonary TB (Figure 1).

| Investigation | n (Patients inwhich investigationsperformed) | Yield ofdiagnostic testn /% |

| Barium meal and follow through | 70 | 58/83 |

| Barium enema | 34 | 15/44 |

| Ultra sound | 93 | 82/88 |

| CT Scan Abdomen | 35 | 28/80 |

| Histopathology of surgical specimen | 35 | 35/100 |

| Histopathology of Colonoscopic biopsy 35 | 29/83 | |

| Histopathology of ultrasound and CT guided biopsy | 28 | 14/50 |

| Histopathology of Laparoscopic biopsy 5 | 5/100 | |

| Histopathology of upper GI endoscopic biopsy | 10 | 4/40 |

| AFB culture | 87 | 6/7 |

Histopathology: Histopathology was the basis of diagnosis in 87/113 patients. Diagnostic yield of histopathology on biopsy in abdominal TB was variable depending upon the method used to take the biopsy. Diagnostic yield of tuberculosis on surgical specimen were found in 35/35 (100%) patients. Biopsies obtained by colonoscopy had a yield of 29/35 (83%) and Ultrasound or CT guided biopsy of the viscera, omentum or LN suggestive of tuberculosis in 14/28 (50%) of patients. Diagnostic laparoscopic peritoneal biopsy was positive for abdominal tuberculosis in all (100%) patients. On the other hand biopsies taken during upper GI endoscopy favored diagnosis in 4/10 (40%) patients.

Common histological features on biopsy specimen was the presence of non caseating granuloma in 59/87 (68%) patients; however a central caseation was noted only in 22/87 (25%) cases and in 6/87 (7%) patients, chronic inflammatory cells infiltration but no definite granuloma was seen.

Samples (ascetic fluid, omental or intestinal biopsy tissues) were sent for acid-fast bacilli culture. The positive yield for acid-fast culture was only in 6/87 (7%) patients, all were on ascetic fluid.

In five (2.3%) patients with suggestive clinical history and negative diagnostic workup, response to therapeutic trial of anti TB drugs was the basis of diagnosis.

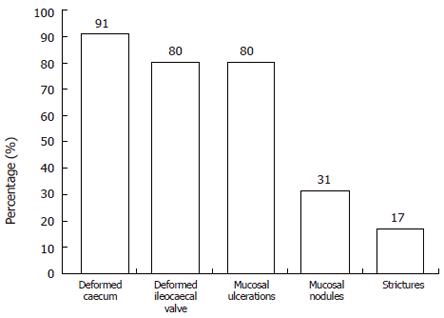

Colonoscopic findings in 35 patients revealed deformed caecum in 32 (91%), irregular ileocaecal valve in 28 (80%), colonic mucosal ulcerations in 28 (80%), mucosal nodules in 11 (31%), and colonic strictures in 6 (17%) patients (Figure 2).

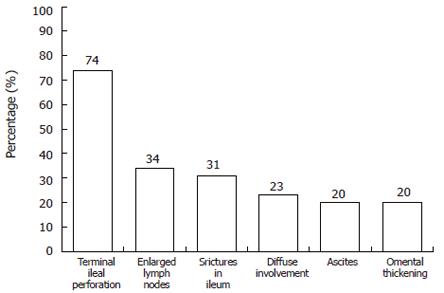

Laparotomy was performed in 35/209 (17%) of patients and notable findings were terminal ileal perforation in 26 patients, enlarged lymph nodes in 12, strictures in ileum in 11, diffuse involvement of the visceral and parietal peritoneum in 8, ascites in 7 and omental thickening in 7 patients (Figure 3).

Based upon predominant clinical features and investigations, site of abdominal TB involvement was intestinal in 103 (49%), peritoneal in 87 (42%), solid viscera in 10 (5%) and nodal in 9 (4%) patients (Figure 4).

Antituberculous treatment was given to all patients. 158/209 (76%) patients responded to medical treatment alone and 35 (17%) patients with complications at admission required additional surgical intervention. Antituberculous treatment was comprised of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol or streptomycin and pyrazinamide in various combination for a period of 9 to 12 mo. A follow-up of 425 ± 120 d was available in 197 (94%) patients. No patient showed a relapse of disease during this follow-up period. However three patients developed drug induced hepatitis. Two of them recovered with modification of drug therapy and one 42 year old female patient developed hepatic encephalopathy and died. In total 12 (6%) patients died due to various complications; eight of them were those who underwent surgery for the complications of abdominal tuberculosis.

Current series of abdominal tuberculosis patients without HIV have highlighted several important considerations. Female predominance was shown as one characteristic feature of abdominal tuberculosis in several studies in the past and also evident in our current series with females contributing to 59% of all patients. Possible reasons for female predominance apart from malnutrition, illiteracy, and poor access to health care facility may be contiguous spread from tuberculous salpingitis[6,11,12]. In contrast, a study from India showed 69.4% patients with ATB were male[3,13].

The most frequent symptom at presentation was abdominal pain, which was present in 93% of patients in our study. Mid abdominal colicky pain represented intermittent small bowel obstruction and was seen in 90%-100% of patients in other studies as well[14]. This highlight the non-specific nature of abdominal pain and common feature that is present in abdominal malignancy and Crohn’s disease[6,12].

Radiological investigation is the mainstay in making presumptive diagnosis of abdominal TB[12,15], this include chest x-rays, ultrasound or CT scan abdomen and barium studies. In this review, half of the patients (53%) had suggestive radiological findings on barium study, CT scan and or ultrasound abdomen. In another review, barium study was supportive of diagnosis of ATB in 60% of patients[1]. However CT scan of the abdomen, which is a costly investigation, gives a better view of intestinal and extra intestinal structures[16]. In our series 28 (13.4%) patients had CT scan of the abdomen with supportive features. Another interesting feature in the present series is the evidence of concomitant pulmonary tuberculosis on chest x-rays in 134 (64%) patients out of these 10 (4.8%) patients had features suggestive of active pulmonary TB. In the literature, associated active pulmonary TB is highly variable and is reported up to 29%[3,17]. Diagnosis made on the basis of radiology is rapid, easy and less expensive but it is presumptive and cannot exclude completely other diseases like Crohn’s disease and malignancies of solid abdominal viscera[18].

Colon and terminal ileum are the most common site of involvement in intestinal variety of tuberculosis and in this regard colonoscopic images and biopsies are considered to be a quick and good diagnostic tool. In the present series, colonoscopy was helpful in making diagnosis in 35 patients, out of them in 29/35 patients, colonoscopic biopsies were positive for presence of granuloma. Colonoscopy also helps in differentiating the colonic tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease[19]. In patients with intestinal TB on colonoscopy, ulcers, strictures, nodules, pseudo polyps, fibrous bands, fistulas, and deformed ileocaecal valve are seen. Mucosal ulcers in intestinal TB tend to be circumferential and are usually surrounded by inflammed mucosa. The ileocaecal valve is either patulous or destroyed in ATB and in few cases it is like fish mouth opening. On the other hand colonoscopic features that favor Crohn’s disease such as aphthous ulcers with normal surrounding mucosa skipped lesions or the presence of cobble stoning[19].

Laparoscopy and biopsy is safe and may help in diagnosing peritoneal TB because of increased peritoneal involvement. In different studies, laparoscopy was found helpful in the diagnosis up to 87%-92% of peritoneal tuberculosis[20,21]. Peritoneal biopsy via mini-laparotomy should be considered if laparoscopy is non-diagnostic[21,22].

Demonstrating tuberculous granuloma is probably the most important investigation for a definitive diagnosis of ATB. In our series of patients, histo-pathology was the basis of diagnosis in 87/209 patients; however a typical granuloma with caseation was found only in 22/87 of patients in our series. Moreover in our patients the yield of demonstrating tuberculous granuloma was high when the specimen was taken surgically or through laparoscopy but it is invasive, expensive and not easily available. On colonoscopic biopsies, if granuloma is non-caseating, interpretation is difficult because Crohn’s disease cannot be excluded[16].

Many authors advocated therapeutic trial with anti tubercular therapy but it should not be encouraged routinely as it may delay the diagnosis of malignancy, lymphoma and Crohn’s disease[1,23]. In the present series, 5 (2%) patients with suggestive history but negative workup, therapeutic trial of anti TB drugs therapy (ATT) was the basis of diagnosis. In the literature up to 40% patients were given therapeutic trial of anti TB drugs[1].

Intestinal TB was the predominant form in this cohort of patients and accounted for 103 (49%) of patients. The majority of patients in this review have ileocaecal involvement. This is in agreement with other reviews on abdominal tuberculosis in which intestinal type of abdominal tuberculosis was ranged from 50%-78%[14]. In one study, jejuneoileal and ileocaecal involvement was more than 75% of all gastrointestinal TB[2]. Relatively common involvement of terminal ileum in intestinal tuberculosis is due to either physiological stasis, large surface area of this part of the intestine, complete digestion of food and abundant lymph nodes in the region[9].

The other, commoner type of abdominal tuberculosis in our patients was peritoneal TB, seen in 87 (42%) patients. In the literature, peritoneal TB involvement is around 43%[9]. Typically exudative fluid with predominant lymphocytes is seen in ascetic fluid but efforts should be made to establish tissue diagnosis by peritoneal biopsy[21].

Response to anti tubercular drugs is generally very good. In our series 158 (76%) patients responded to medical treatment alone and 35 (17%) patients who presented with complications at the time of admission required additional surgery. Other studies have also shown the similar frequency of surgical intervention in patients with abdominal tuberculosis that is around 20%-40%[24].

None of our patients showed signs of relapse after 14 mo follow-up. Twelve patients in this series died; eight of them post operatively. A possible reason for increased mortality in operated patients may be due to late presentation and previous complications like malnutrition, perforation and sepsis.

Mortality due to abdominal tuberculosis ranged from 8 to 50 percent in various series. Advanced age, delay in initiating therapy, and underlying cirrhosis have been associated with higher mortality rates[13,22].

One of the limitations in this study is the retrospective nature of the data set but it doesn’t interfere with the objective of the study. Secondly, all tests were not done in every patient because each test is not indicated in every case. The other limitation was the inability to confirm diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis either by culture of Acid Fast Bacilli or by PCR in all cases. Yield of AFB culture on biopsy specimen and ascetic fluid is low[1]. Polymerase Chain Reaction is not yet standardized in diagnosis of tuberculosis[25].

In conclusion, abdominal TB is a complex disease and has diverse symptomatology that is non-specific. Tissue diagnosis is mandatory for appropriate management but it is invasive, expensive and unfortunately not always conclusive either. A high index of clinical suspicion is required along with the help of multiple adjuvant diagnostic tools for diagnosis of ATB. Until the time when we have a specific test for diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis, this remains a challenge for physician.

| 1. | Kapoor VK. Abdominal tuberculosis. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74:459-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Horvath KD, Whelan RL. Intestinal tuberculosis: return of an old disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:692-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang HS, Chen WS, Su WJ, Lin JK, Lin TC, Jiang JK. The changing pattern of intestinal tuberculosis: 30 years' experience. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:569-574. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Misra SP, Misra V, Dwivedi M, Gupta SC. Colonic tuberculosis: clinical features, endoscopic appearance and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:723-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aston NO. Abdominal tuberculosis. World J Surg. 1997;21:492-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Singhal A, Gulati A, Frizell R, Manning AP. Abdominal tuberculosis in Bradford, UK: 1992-2002. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:967-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Talwar BS, Talwar R, Chowdhary B, Prasad P. Abdominal tuberculosis in children: an Indian experience. J Trop Pediatr. 2000;46:368-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pulimood AB, Ramakrishna BS, Kurian G, Peter S, Patra S, Mathan VI, Mathan MM. Endoscopic mucosal biopsies are useful in distinguishing granulomatous colitis due to Crohn's disease from tuberculosis. Gut. 1999;45:537-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Geake TM, Spitaels JM, Moshal MG, Simjee AE. Peritoneoscopy in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:66-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Update: tuberculosis elimination--United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1990;39:153-156. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kapoor VK. Abdominal tuberculosis: the Indian contribution. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1998;17:141-147. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Bolukbas C, Bolukbas FF, Kendir T, Dalay RA, Akbayir N, Sokmen MH, Ince AT, Guran M, Ceylan E, Kilic G. Clinical presentation of abdominal tuberculosis in HIV seronegative adults. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mehta JB, Dutt A, Harvill L, Mathews KM. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. A comparative analysis with pre-AIDS era. Chest. 1991;99:1134-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 28-1983. A 35-year-old woman with abdominal pain and a right-lower-quadrant mass. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:96-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kapoor VK. Koch's or Crohn's: the debate continues. Int J Clin Pract. 1997;51:532. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hulnick DH, Megibow AJ, Naidich DP, Hilton S, Cho KC, Balthazar EJ. Abdominal tuberculosis: CT evaluation. Radiology. 1985;157:199-204. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Werbeloff L, Novis BH, Bank S, Marks IN. The radiology of tuberculosis of the gastro-intestinal tract. Br J Radiol. 1973;46:329-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bhargava DK, Kushwaha AK, Dasarathy S, Shriniwas P. Endoscopic diagnosis of segmental colonic tuberculosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:571-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ibrarullah M, Mohan A, Sarkari A, Srinivas M, Mishra A, Sundar TS. Abdominal tuberculosis: diagnosis by laparoscopy and colonoscopy. Trop Gastroenterol. 2002;23:150-153. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Sanai FM, Bzeizi KI. Systematic review: tuberculous peritonitis--presenting features, diagnostic strategies and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:685-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chow KM, Chow VC, Hung LC, Wong SM, Szeto CC. Tuberculous peritonitis-associated mortality is high among patients waiting for the results of mycobacterial cultures of ascitic fluid samples. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:409-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Palmer KR, Patil DH, Basran GS, Riordan JF, Silk DB. Abdominal tuberculosis in urban Britain--a common disease. Gut. 1985;26:1296-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Murphy TF, Gray GF. Biliary tract obstruction due to tuberculous adenitis. Am J Med. 1980;68:452-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Al Zahrani K, Al Jahdali H, Poirier L, René P, Gennaro ML, Menzies D. Accuracy and utility of commercially available amplification and serologic tests for the diagnosis of minimal pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1323-1329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Alpnini GD E- Editor Ma WH