Published online Jan 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.426

Revised: June 28, 2005

Accepted: July 15, 2005

Published online: January 21, 2006

AIM: Endoscopic metal stenting (EMS) offers good results in short to medium term follow-up for bile duct stenosis associated with chronic pancreatitis (CP); however, longer follow-up is needed to determine if EMS has the potential to become the treatment of first choice.

METHODS: EMS was performed in eight patients with severe common bile duct stenosis due to CP. After the resolution of cholestasis by endoscopic naso-biliary drainage three patients were subjected to EMS while, the other five underwent EMS following plastic tube stenting. The patients were followed up for more than 5 years through periodical laboratory tests and imaging techniques.

RESULTS: EMS was successfully performed in all the patients. Two patients died due to causes unrelated to the procedure: one with an acute myocardial infarction and the other with maxillary carcinoma at 2.8 and 5.5 years after EMS, respectively. One patient died with cholangitis because of EMS clogging 3.6 years after EMS. None of these three patients had showed symptoms of cholestasis during the follow-up period. Two patients developed choledocholithiasis and two suffered from duodenal ulcers due to dislodgement of the stent between 4.8 and 7.3 years after stenting; however, they were successfully treated endoscopically. Thus, five of eight patients are alive at present after a mean follow-up period of 7.4 years.

CONCLUSION: EMS is evidently one of the very promising treatment options for bile duct stenosis associated with CP, provided the patients are closely followed up; thus setting a system for their prompt management on emergency is desirable.

- Citation: Yamaguchi T, Ishihara T, Seza K, Nakagawa A, Sudo K, Tawada K, Kouzu T, Saisho H. Long-term outcome of endoscopic metallic stenting for benign biliary stenosis associated with chronic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(3): 426-430

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i3/426.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.426

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is reported to become complicated with bile duct stenosis in about 5-40% of the patients[1,2].The severity of the stenosis varies; however, radical treatment is needed for serious cases presenting persistent cholestasis, jaundice or cholangitis. Moreover, it has been shown that long-standing biliary stenosis, even if mild or moderate, often causes liver damage[3,4]. Half of these patients will present liver fibrosis by the time of decompression[3].

Non-surgical treatment has been reported to be comparable with surgery, with lower morbidity and mortality. Especially, endoscopic biliary drainage (ERBD) using a plastic tube stent has been adopted as the first-line treatment, and there are many reports concerning the usefulness of ERBD[5,6]. Although plastic stents offer satisfactory short-term drainage, medium to long-term results have been disappointing because of stent clogging or migration[6,7], and surgical treatment is chosen for a permanent palliation. However, surgical treatment is associated with important morbidity[8].

ERBD using a metallic stent (EMS) is useful for malignant biliary stricture since a relatively long-term non-surgical palliation can be attained[9]. In contrast, EMS for a benign biliary stricture is still controversial[10,11]. Furthermore, there have been few reports on EMS for biliary stenosis due to CP. Deviere et al reported favorable results with the self-expandable metal mesh stent for biliary obstruction due to CP, but the long-term results have not been reported[12]. In this study, we intended to clarify the outcome of patients with biliary stenosis due to CP who underwent EMS and have been followed up for more than 5 years.

Between July 1996 and August 1998, EMS was performed in eight patients with severe common bile duct stenosis associated with CP in our institution. We had experienced 64 patients with CP during that period in the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) division. The indication for EMS was intractable bile duct stenosis uncontrollable by plastic tube biliary drainage. Ten patients gave their informed consent and the procedure was approved by the Ethical Committee of our institute; however, one patient underwent surgical treatment and another was lost to follow-up. They were all males with a median age of 65.7 years (range: 42-78 years). The etiology of CP was alcohol abuse in seven and idiopathic in one. Underlying diseases were diabetes mellitus in five patients, angina pectoris in one and early colon cancer in one. Mean duration of the illness before manifesting the first symptoms of bile duct stenosis was 3.7 years.

On their first admission, five patients presented with abdominal pain, six had symptomatic jaundice, and six had cholangitis (Table 1). Serum alkaline phosphatase concentration (ALP) was three times or more the upper limit of normal (mean 1 815 U/L; range 984-3 358) in all the patients. Similarly, serum conjugated bilirubin (D-Bil) was elevated above the upper limit of normal (mean 3.45 mg/dL; range 1.2-7.4) in seven patients. Abdominal ultrasonography and CT scan demonstrated marked dilatation of the common bile duct and slight to moderate dilatation of the intra-hepatic bile duct.

| Patientnumber | Age (yr) | Sex | Cause ofCP | Underlyingdiseases | Jaundice | Cholangitis |

| 1 | 78 | Male | Alcohol | Angina Pectoris | + | + |

| 2 | 53 | Male | Alcohol | DM | - | + |

| 3 | 42 | Male | Alcohol | DM, Colon cancer | + | - |

| 4 | 43 | Male | Alcohol | - | - | |

| 5 | 77 | Male | Alcohol | + | + | |

| 6 | 53 | Male | Alcohol | DM | + | + |

| 7 | 70 | Male | Alcohol | DM | + | + |

Endoscopic naso-biliary drainage (ENBD) using a 7-Fr. Plastic tube was performed in all the patients as the initial treatment. At that time, cholangiography showed almost complete obstruction or severe stenosis of the lower part of common bile duct. After the resolution of symptoms and laboratory findings of cholestasis by ENBD, three patients were subjected to EMS, while the other five underwent EMS after stenting using a 10 Fr. tube. The mean duration of tube stenting was 1.4 mo (range, 2-7 mo). Three patients developed clogging of the tube stent and subsequently the stent was changed by an EMS. In the other two patients, the tube stents were withdrawn; however, symptoms of re-obstruction were detected within 3 mo and thus EMS was performed.

For EMS, a non-covered, non-self-expandable stent (Strecker stent) was used in two patients and a self-expandable stent (Wallstent, Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, MA, USA) was used in the other six patients, the length and internal diameter of the stents were 4 and 5 cm, 7 and 10 cm after full expansion, respectively.

In four patients, plastic tube stents were inserted to resolve the main pancreatic duct stenosis, and they were occasionally inserted depending on the patient’s symptoms: abdominal and/or back pain.

After EMS, periodical examination of hemogram, blood biochemistry, urinalysis, and abdominal ultrasonography were conducted every 3-4 mo. Examination by cholangiography was occasionally performed, when a patient presented symptoms of biliary obstruction.

| Patient number | Cholestasis | Cholangitis | Stone formation | Dislodgement | Alcohol intake | Outcome | Duration of stent patency(yr) |

| 1 | + 1 mo | + 1 mo | - | - | - | Dead | 2.8 |

| 2 | + 4.6 yr | - | - | - | - | Alive | 8.3 |

| 3 | + | - | + 7.3 yr | + 5.9 yr | + | Alive | 7.3 |

| 4 | - | - | - | - | - | Alive | 7.1 |

| 5 | - | - | - | + 4.8 yr | - | Alive | 6.9 |

| 6 | - | - | - | - | - | Dead | 5.5 |

| 7 | + | - | + 6.1 yr | - | + | Alive | 6.1 |

| 8 | + 3.6 yr | + 3.6 yr | - | - | + | Dead | 3.6 |

EMS was successfully performed in all the patients; however, in one patient (no. 1) clogging was observed within 1 mo and another EMS was inserted inside the first EMS. The patient showed no symptoms of bile duct obstruction thereafter.

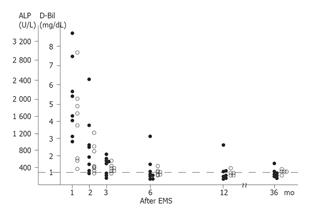

The serum concentration of ALP and D-bil markedly decreased after the initial treatment including EMS (Figure 1), and 1 year after EMS, five of eight patients showed normal values, two patients showed slightly higher than the upper limit of normal, and one patient had a high serum concentration of ALP. Two years after EMS, none of the patients showed symptoms of bile duct obstruction and abdominal US demonstrated no dilatation of the intra-hepatic bile duct with the stent located at the original position.

One patient (no. 1) died of acute myocardial infarction 2.8 years after EMS without symptoms of cholestasis during the follow-up period. The course of the other seven patients was uneventful for 3 years.

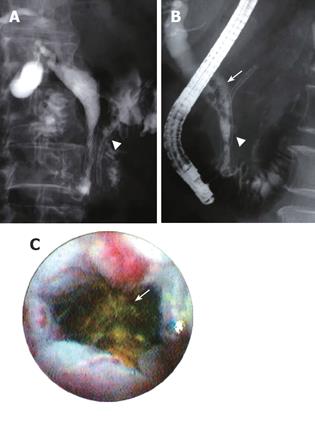

One patient (no. 8) died of cholangitis (acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis, AOSC) caused by EMS clogging 3.6 years after EMS. The patient had presented no symptoms up to 1 wk before the last admission, when he felt acute pain in the right upper abdomen and experienced a sudden rise of his body temperature. He was brought to the hospital in a state of shock and was admitted to the ICU, but intensive care including ENBD was not effective and he died 17 d after the last admission. The patient’s periodical check up with US and laboratory tests showed no signs of marked cholestasis except slight elevation of serum ALP concentration during the 3.5 years of follow-up as well as 1 mo before. It was suggested from the medical chart that the patient had suffered from cholangitis caused by stent clogging 1 wk before his admission, but he did not take it seriously; he thought that the symptoms were those of common cold, and delayed his visit to the hospital. Another patient (no. 2) presented with signs of cholestasis caused by acute exacerbation of pancreatitis 4.6 years after EMS; however, his condition improved soon after the treatment for pancreatitis without any endoscopic treatment, and he showed no symptoms thereafter. Two other patients (nos. 3 and 7) presented with cholestasis caused by choledocholithiasis in the upper part of the CBD proximal to the stent 7.3 and 6.1 years after EMS, respectively. In one patient (no. 7) the stones were successfully removed with a basket wire and he presented no symptoms thereafter (Figures 2A and 2B). In the other patient (no. 3) the stone could not be removed with a basket wire and two sessions of endoscopic hydraulic lithotripsy were necessary to eliminate it. Cholangioscopic examination of these patients showed that the metallic mesh was embedded into the bile duct wall allowing sufficient inner space without epithelial hyperplasia within the stent (Figure 2C).

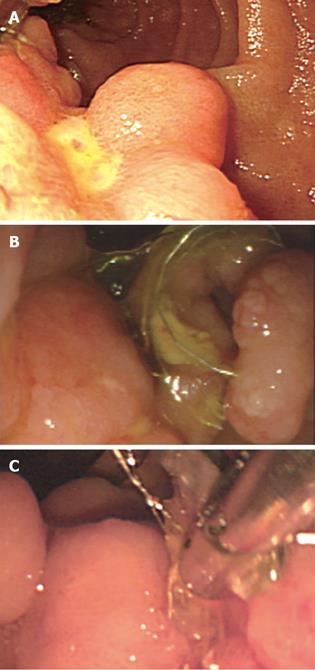

Two patients (nos. 3 and 5) suffered from duodenal ulcers at 5.9 and 4.8 years after EMS, respectively, because the EMS wire dislodged and protruded from the papillary orifice, contacting the duodenal wall on the opposite side. The wire of the protruding part was cut under endoscopy with the end-cutter (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and the ulcer healed later (Figure 3).

Patient (no. 6) died of maxillary carcinoma 5.5 years after EMS although he presented no symptoms of cholestasis during the follow-up period.

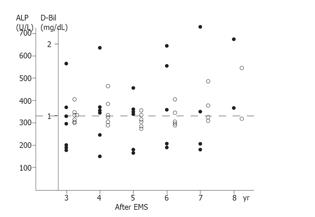

Thus, five of the eight patients are alive at present and their mean follow-up period is already 7.4 (range: 6.5-8.3 years) years. The value of ALP is over the upper limit of normal in three patients now (Figure 4), and mild dilatation of the intra-hepatic bile duct is observed in three of them.

Patients (nos. 3, 6, 7, and 8) continued drinking alcohol after EMS; two of them developed choledocholithiasis and one suffered from AOSC. The other four patients did not drink alcohol after EMS and only one showed mild, transient signs of cholestasis.

EMS for benign bile duct stenosis as a complication of CP has been attempted in some institutes and patency of the stent is likely to be better[12-16]. Kahl et al used metal stents as the permanent treatment option and their patients remained free of obstructive jaundice or cholangitis for 1 year[16]. Deviere et al conducted a prospective study with a mean follow-up of 33 mo, and the stent lumen remained patent and functional throughout the follow-up period[12]. The reported results agree with our study concerning short to medium-term follow-up after EMS. In fact within 3 years after the treatment, all the patients except one who died of a heart attack showed almost uneventful clinical courses regarding biliary stenosis; judging from symptoms, laboratory findings including ALP, D-Bil, and imaging findings. One elderly patient died of causes other than CP with no signs of bile duct re-obstruction for 2.8 years. Such a good outcome was not achieved with the plastic tube stent[5,6,8,9,17], and long-term outcome of treatment with multiple tube stents was also disappointing[18].

Based on these results, EMS is obviously better than tube stenting regarding patency and not requiring scheduled changing of the stent. These advantages are thought to come from the characteristics of EMS: large caliber and expanding effect. However, the main problem of EMS is the development of epithelial hyperplasia in the stent resulting in obstruction[18]. Deviere et al reported that only two of 20 patients developed epithelial hyperplasia leading to cholestasis and jaundice within six months after stenting[12]. One of our patients also developed early obstruction of EMS, but an additional stent resolved this difficult problem. The metallic mesh is thought to become embedded in the bile duct wall early after stenting, so that a continuous membrane covers the inner stent[12]. Based on this hypothesis, ingrowth within the stent and subsequent obstruction may be related to the tumor rather than to CP, and in fact, the majority of our patients did not develop an early obstruction.

Although good results have been reported after a short- to medium-term follow-up, long-term results are unknown. Hastier et al reported the outcome of a patient treated with a metallic stent, who presented with no evidence of recurrence of cholestasis or episodes of cholangitis for a relatively long period of 3 years[14]. Van Berkel et al recently reported that they treated 13 patients with biliary stricture due to CP by self-expanding metal stent (SEMS) with the mean follow-up for 50 mo and that SEMS was found to be safe and provides successful as well as prolonged drainage in selected patients[19]. Nevertheless, the opinions in our institute were controversial regarding uncertainty of safety and outcome of EMS in patients with CP after a long-term follow-up, and we voluntarily decided to stop the application of EMS treatment from August 1998 until December 2003, when we could assess the long-term outcome and re-started EMS. Since then, two patients have been subjected to EMS up to now.

The outcome of EMS after more than 3 years was fairly good. But we experienced a very serious complication caused by re-obstruction of the bile duct. Emergency treatment was delayed leading to disappointing results in this case. If adequate intensive treatment had been started much earlier, the patient would have been saved. Another patient showed mild cholestatic symptom due to acute exacerbation of pancreatitis, but recovered soon after pancreatitis resolved without any intervention, suggesting cholestasis was not caused by clogging of the stent but by another factor such as papillary edema. In two other patients with stone formation, cholangioscopic findings showed the patency of the stent lumen, according to the assumption of Deviere et al[12]. However, stones were thought to develop as a consequence of stagnation of bile, accordingly complete bile flow may be difficult to obtain even with EMS. Another complication of dislodgement was duodenal ulcers which were well controlled by endoscopic treatment.

One of our patients died of maxillary cancer long after EMS. Hastier et al decided to insert a metallic stent in their patient in view of his poor prognosis associated with the pulmonary malignancy[14]. CP is shown to frequently associate with various malignancies and a significantly lower survival rate compared with non-CP[20-22]. Therefore, in choosing EMS, this is one of the decision-making facts as well as the patients' general conditions and the lack of response to stenting using a plastic tube[2,13].

It is difficult to determine the optimal indications for EMS from our results because of the limited number of patients and the absence of a control group. However, since five of the eight patients are alive and leaving ordinary lives 7.4 years after EMS, this procedure is evidently one of the very promising options of treatment for bile duct stenosis in patients with CP, provided they are closely followed up through periodical check-ups. Thus setting a system for prompt management in case of an emergency is desirable. In addition, our results indicate that alcohol intake may be related to the poorer prognosis of patients subjected to EMS; thus prohibition of alcohol consumption is essential.

| 1. | Wilson C, Auld CD, Schlinkert R, Hasan AH, Imrie CW, MacSween RN, Carter DC. Hepatobiliary complications in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 1989;30:520-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schutz SM, Baillie J. Another treatment option for biliary strictures from chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1023-1024. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lesur G, Levy P, Flejou JF, Belghiti J, Fekete F, Bernades P. Factors predictive of liver histopathological appearance in chronic alcoholic pancreatitis with common bile duct stenosis and increased serum alkaline phosphatase. Hepatology. 1993;18:1078-1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hammel P, Couvelard A, O'Toole D, Ratouis A, Sauvanet A, Fléjou JF, Degott C, Belghiti J, Bernades P, Valla D. Regression of liver fibrosis after biliary drainage in patients with chronic pancreatitis and stenosis of the common bile duct. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:418-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Devière J, Devaere S, Baize M, Cremer M. Endoscopic biliary drainage in chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:96-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Barthet M, Bernard JP, Duval JL, Affriat C, Sahel J. Biliary stenting in benign biliary stenosis complicating chronic calcifying pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 1994;26:569-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Godil A, Chen YK. Endoscopic management of benign pancreatic disease. Pancreas. 2000;20:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Smits ME, Rauws EA, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Long-term results of endoscopic stenting and surgical drainage for biliary stricture due to chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:764-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Menon K, Romagnuolo J, Barkun AN. Expandable metal biliary stenting in patients with recurrent premature polyethylene stent occlusion. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1435-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yoon HK, Sung KB, Song HY, Kang SG, Kim MH, Lee SG, Lee SK, Auh YH. Benign biliary strictures associated with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: treatment with expandable metallic stents. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1523-1527. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lopez RR, Cosenza CA, Lois J, Hoffman AL, Sher LS, Noguchi H, Pan SH, McMonigle M. Long-term results of metallic stents for benign biliary strictures. Arch Surg. 2001;136:664-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Deviere J, Cremer M, Baize M, Love J, Sugai B, Vandermeeren A. Management of common bile duct stricture caused by chronic pancreatitis with metal mesh self expandable stents. Gut. 1994;35:122-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kahl S, Zimmermann S, Genz I, Glasbrenner B, Pross M, Schulz HU, Mc Namara D, Schmidt U, Malfertheiner P. Risk factors for failure of endoscopic stenting of biliary strictures in chronic pancreatitis: a prospective follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2448-2453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hastier P, Buckley JM, Peten EP, Dumas R, Delmont J. Long term treatment of biliary stricture due to chronic pancreatitis with a metallic stent. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1947-1948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Van Westerloo DJ, Bruno MJ, Bergman JJ, Cahen DL, van Berkel AM. Self-expandable wallstents for distal common bile duct strictures in chronic pancreatitis. Follow-up and clinical outcome of 15 patients. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:A913. |

| 16. | Kahl S, Zimmermann S, Glasbrenner B, Pross M, Schulz HU, McNamara D, Malfertheiner P. Treatment of benign biliary strictures in chronic pancreatitis by self-expandable metal stents. Dig Dis. 2002;20:199-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Farnbacher MJ, Rabenstein T, Ell C, Hahn EG, Schneider HT. Is endoscopic drainage of common bile duct stenoses in chronic pancreatitis up-to-date. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1466-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mastrović Z. [Ankylosing spondylitis as a social and medical problem]. Reumatizam. 1975;22:169-176. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Cahen DL, van Berkel AM, Oskam D, Rauws EA, Weverling GJ, Huibregtse K, Bruno MJ. Long-term results of endoscopic drainage of common bile duct strictures in chronic pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:103-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, Ammann RW, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, DiMagno EP, Andrén-Sandberg A, Domellöf L, Di Francesco V. Prognosis of chronic pancreatitis: an international multicenter study. International Pancreatitis Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1467-1471. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lankisch PG. Natural course of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2001;1:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Malka D, Hammel P, Maire F, Rufat P, Madeira I, Pessione F, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P. Risk of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2002;51:849-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Liu WF