Published online Jun 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i24.3866

Revised: February 10, 2006

Accepted: February 20, 2006

Published online: June 28, 2006

AIM: To evaluate the effect of three interventional treatments involving transvenous obliteration for the treatment of gastric varices, and to compare the efficacy and adverse effects of these methods.

METHODS: From 1995 to 2004, 93 patients with gastric fundal varices underwent interventional radiologic embolotherapy at our hospital. Of the 93 patients, 75 were treated with the balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) procedure; 8 were with the percutaneous transhepatic obliteration (PTO) procedure; and 10 were with the combined BRTO and PTO therapy. A follow-up evaluation examined the rates of survival, recurrence and rebleeding of the gastric varices, worsening of esophageal varices and complications in each group.

RESULTS: The BRTO, PTO, and combined therapy were technically successful in 81% (75/93), 44% (8/18), and 100% (10/10) patients, respectively. Recurrence of gastric varices was found in 3 patients in the BRTO group and in 3 patients in the PTO group. Rebleeding was observed in 1 patient in the BRTO group and in 1 patient in the PTO group. The 1- and 3-year survival rates were 98% and 87% in the patients without hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the BRTO group, 100% and 100% in the PTO group, and 90% and 75% in the combined therapy group, respectively.

CONCLUSION: Combined BRTO and PTO therapy may rescue cases with uncontrollable gastric fundal varices that remained even after treatment with BRTO and/or PTO, though there were limitations of our study, including retrospective nature and discrepancy in sample size between the BRTO, PTO and combined therapy groups.

- Citation: Arai H, Abe T, Takagi H, Mori M. Efficacy of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration, percutaneous transhepatic obliteration and combined techniques for the management of gastric fundal varices. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(24): 3866-3873

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i24/3866.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i24.3866

Currently, various types of therapeutic procedures, including surgery, endoscopic procedures, and direct therapeutic intervention, are available for the treatment of gastric varices. Interventional therapy for gastric varices is classified as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) and transcatheter embolotherapy. Many studies have reported the use of TIPS in patients with gastric varices[1-5]. Although interventional embolotherapy has been applied for the treatment of gastric varices and a recent study has shown that embolotherapy may control gastric varices better than TIPS, treatment indications and a recommended embolotherapeutic strategy for the eradication of gastric fundal varices have not yet been strictly established[5-10]. In this study, we evaluated the effect of three interventional treatments involving transvenous obliteration for the treatment of gastric varices; the efficacy and adverse effects of these methods were compared. The present study involved 93 patients in whom interventional embolotherapy was performed as a treatment for gastric fundal varices. In addition, 10 of the 93 patients were treated with a combined balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) and percutaneous transhepatic obliteration (PTO) therapy, and the clinical efficacy, the complications and outcomes of this therapy were investigated. The aim of this retrospective study was to evaluate the effect of interventional embolotherapy, in particular the clinical efficacy of combined therapy, for the treatment of patients with gastric fundal varices.

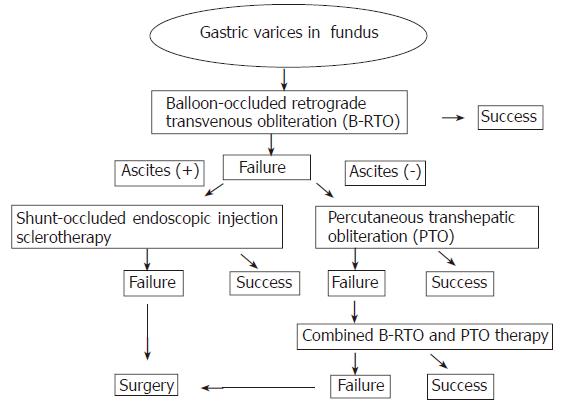

From 1995 to 2004, 93 patients with gastric fundal varices underwent interventional radiologic embolotherapy at our hospital. The algorithmic strategy used for the treatment of gastric fundal varices in our hospital is shown in Figure 1. According to the treatment algorithm, all the patients were first treated with the BRTO procedure. When the BRTO procedure could not obliterate the gastric varices because of collateral venous drainage, the PTO procedure was chosen as the second line of treatment. When neither the BRTO nor the PTO procedure could obliterate the gastric varices, the patients were treated with a combination of BRTO and PTO as the third line of treatment. Of the 93 patients, 75 were treated with the BRTO procedure; 8 were with the PTO procedure; and 10 were with the combined therapy. The characteristics of the 93 patients are shown in Table 1. The study included 47 men and 46 women with a mean age of 63 years. Table 1 shows the underlying cause of portal hypertension, the presence of serum hepatitis virus markers, and modified Child’s classification of the patients[11]. Left-side portal hypertension due to splenic vein obstruction after traumatic pancreatitis was observed in 1 patient. Patients with Child’s class C cirrhosis with ascites were excluded from this study because interventional radiologic embolotherapy may increase the portal pressure[12]. Of the 93 patients, 37 (40%) underwent treatment of esophageal varices prior to treatment of gastric varices. 21 (23%) had complications due to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography could be used to exclude the presence of portal tumor thrombus in all patients who had HCC. Patients with portal vein thrombus were excluded.

| Clinical characteristics | BRTO | PTO | Com-T | Total |

| Sex (M/F) | 37/38 | 5/3 | 5/5 | 47/46 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 63.4 ± 10.0 | 62.9 ± 8.4 | 68.9 ± 12.8 | 63.9 ± 10.2 |

| Cause of portal hypertension | ||||

| Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | 10 (13) | 1 (13) | 3 (30) | 14 (15) |

| HBV (+) liver cirrhosis | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 4 (4) |

| HCV (+) liver cirrhosis | 52 (69) | 6 (75) | 5 (50) | 63 (68) |

| HBV (-) HCV (-) liver cirrhosis | 7 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 8 (9) |

| Idiopathic portal hypertension | 1 (1) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Traumatic | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Presence of Hepatocellular carcinoma | 21 (28) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 21 (23) |

| Child-Pugh class | ||||

| A | 42 (56) | 3 (38) | 7 (70) | 52 (56) |

| B | 29 (39) | 4 (50) | 2 (20) | 35 (38) |

| C | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 3 (3) |

| Location of gastric varices | ||||

| IGV1 | 56 (75) | 2 (25) | 9 (90) | 67 (72) |

| GOV2 | 19 (25) | 6 (75) | 1 (10) | 26 (28) |

| Form of gastric varices | ||||

| Tumorous | 26 (35) | 1 (13) | 2 (20) | 29 (31) |

| Nodular | 49 (65) | 7 (88) | 8 (80) | 64 (69) |

| Previous gastric variceal bleeding | ||||

| Present | 36 (48) | 4 (50) | 2 (20) | 42 (45) |

| Absent | 39 (52) | 4 (50) | 8 (80) | 51 (55) |

| Temporary hemostasis | ||||

| Clipping | 3 (4) | 1 (13) | 2 (20) | 6 (7) |

| EVL | 5 (7) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 6 (7) |

| Histacryl | 3 (4) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) |

| Balloon tamponade | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Spontaneous | 23 (31) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 24 (26) |

| Duration of hospitalization (mean ± SD, d) | 17.9 ± 23.4 | 14.6 ± 12.8 | 10.4 ± 4.0 | 16.8 ± 21.4 |

| Follow-up (mean ± SD, d) | 1040 ± 713 | 600 ± 381 | 704 ± 389 | 966 ± 677 |

| Range (d) | 35 - 2805 | 1134 - 150 | 83 - 1183 | 35 - 2805 |

According to the classification system originally proposed by Sarin et al [13,14], gastric fundal varices are classified as type 2 gastroesophageal varices (GOV2; often long and tortuous, extending from the esophagus below the gastroesophageal junction toward the fundus) or type 1 isolated gastric varices (IGV1; varices located in the fundus that are often tortuous and complex in shape). In our study, 67(72%) patients showed IGV1 and 26 (28%) showed GOV2. The form of fundal varices was massively tumorous in 29 (31%) patients and nodular in 64 (69%).

Gastric fundal varices with active bleeding (spurting or oozing) or signs of recent bleeding or those that were in danger of rupturing were identified for treatment. Variceal bleeding was endoscopically confirmed in all patients immediately after their hematemesis. The bleeding episodes were attributed to ruptured gastric varices based on one of the following criteria: actively bleeding varices at the time of endoscopic examination, presence of adherent clots on varices, or presence of blood in the stomach with gastric varices as the only possible cause of the bleeding. The indications for gastric varices embolization in patients who have not previously had gastric variceal bleeding are as follows: gastric varices with red spots observed during upper intestinal endoscopy or growing gastric varices were considered to be in danger of rupturing.

Bleeding gastric varices were observed in 42 patients, and the remaining 51 patients were prophylactic nonbleeding cases that were in danger of rupturing. An emergency procedure was performed in 14 patients who had active bleeding during urgent endoscopy. To achieve temporary hemostasis, gastric variceal bleeding was treated in the following manner: endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) in 6 patients, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) using cyanoacrylate with lipiodol in 4 patients, clipping treatment in 6 patients, and balloon tamponade in 2 patients. Spontaneous hemostasis was achieved in the remaining 24 patients. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

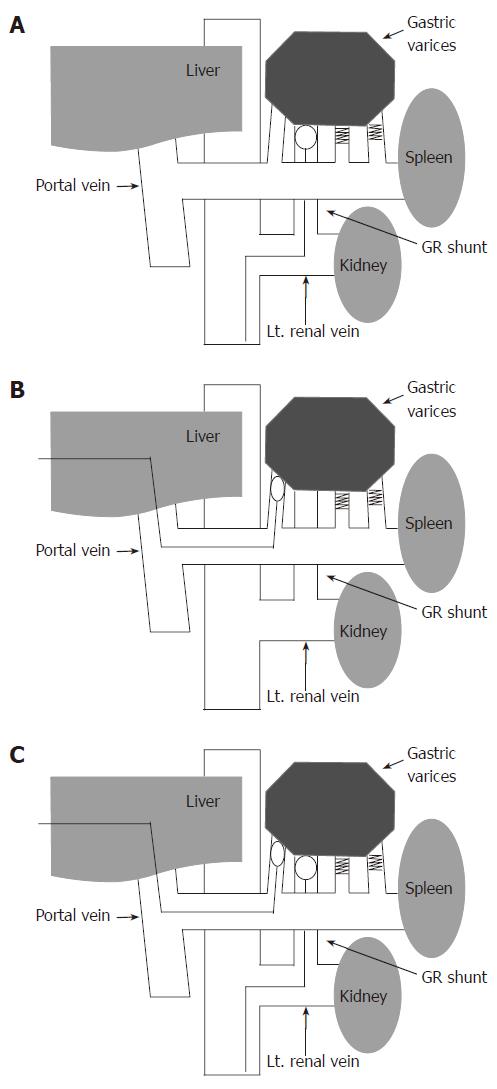

Under local anesthesia, a 6.5-French occlusive balloon catheter with a diameter of 20 mm (Create Medic, Yokohama, Japan) was inserted through the femoral or internal jugular vein into the gastrorenal shunt, gastrocaval shunt, or both. Results of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous varicerography (BRTV) were obtained in advance. Following identification of the gastric varices and their associated feeding and draining veins, the balloon was inflated with CO2. When the gastric varices were visualized and retention of the contrast medium in the gastric varices was identified, a 50 g/L ethanolamine oleate (EO) solution with iopamidol (50 g/L EOI), which contained equal amounts of 100 g/L EO (Grelan, Tokyo, Japan) and iopamidol 300 (Schering, Berlin, Germany), was used as a sclerosant; the solution was slowly infused through the catheter into the gastric varices and their feeding veins in a retrograde manner during balloon occlusion under fluoroscopy. When varices and feeding veins could be shown in their entirety, injection was suspended. If draining minor collaterals were visualized by retrograde transvenous varicerography, microcoils were used in addition to 50 g/L EOI to embolize the collateral veins in order to prevent leakage of the sclerosing agent into the systemic circulation. After the sclerosant had remained in place for 1 h to allow thrombi formation, hemolyzed blood and excess uncoagulated sclerosant were collected through the catheter; subsequently, the balloon was deflated. Immediately prior to the treatment, 4000 U of haptoglobin (Welfide, Osaka, Japan) was administered by drop infusion to prevent renal damage induced by hemolysis due to the use of EO. The PTO procedure was chosen another day later on when retrograde venography showed that retention of the contrast medium was insufficient even though the collateral vessels had been embolized using metallic coils. (Figure 2A)

We believe that the basic goal of embolotherapy in the treatment of gastric varices is to obliterate the variceal lumen and induce submucosal sclerosis. Therefore, in our hospital, PTO is used to obliterate gastric varices by using a sclerosing agent (50 g/L EOI); this procedure differs from the PTO procedure used previously[15]. Percutaneous transhepatic portography (PTP) using a 5-French catheter with a diameter of 11 mm was performed to determine the hemodynamics of the feeding and draining veins of the gastric varices. Due to the presence of multiple feeding veins, a coaxial catheter was inserted into these feeding veins. Some metallic coils were placed in these feeding veins with the exception of one feeding vein. The balloon catheter was selectively inserted into the remaining feeding vein. Through the balloon catheter, antegrade venography was performed with the balloon inflated. When the gastric varices were visualized and retention of the contrast medium in the gastric varices was identified, 50 g/L EOI, as a sclerosant, was slowly injected in the antegrade direction into the gastric varices under fluoroscopy. When varices could be shown in their entirety, injection was suspended. After the sclerosant had remained in place for 1 h to allow thrombi formation, the hemolyzed blood and excess uncoagulated sclerosant were collected through the catheter. Then, the microcoils were used to embolize the remaining feeding vein and to stabilize the thrombus in the gastric varices. Portography was repeated to assess obliteration of the feeding veins and the absence of flow to the gastric varices. Immediately prior to the treatment, 4000 U of haptoglobin was administered by drop infusion. When antegrade venography showed that retention of the contrast medium in the gastric varices was insufficient, combined therapy was chosen (Figure 2B).

The BRTO and PTO procedures were performed simultaneously. In other words, the feeding and the draining veins of gastric varices were simultaneously obliterated by the balloon catheters. Through the balloon catheter in the feeding vein, antegrade venography was performed with the double balloon inflated. When the gastric varices were visualized and retention of the contrast medium in the gastric varices was identified, 50 g/L EOI, as a sclerosant, was slowly injected in the antegrade direction into the gastric varices under fluoroscopy. When varices could be shown in their entirety, injection was suspended. After the sclerosant had remained in place for 1 h to allow thrombi formation, the hemolyzed blood and excess uncoagulated sclerosant were collected through the catheter. Immediately prior to the treatment, 4000 U of haptoglobin was administered by drop infusion (Figure 2C).

A follow-up evaluation was performed to check for recurrence and rebleeding of the gastric varices, the aggravation of esophageal varices, complications, and rates of survival in each procedure group. CT was performed 1 wk after the procedure to evaluate obliteration of the gastric varices. Technical success was defined as complete clotting of the gastric varices that were observed during contrast-enhanced CT scanning 1 wk after the treatment. For patients in whom considerable blood flow remained, interventional embolotherapy was repeated until disappearance of blood flow within the gastric varices was confirmed. Initially, endoscopic examination was performed after 1 wk, 3 and 6 mo of the procedure to evaluate the obliteration of the gastric varices. Later, the examination was performed after every 6 mo or whenever clinically required. The laboratory data, including hepatic and renal function tests, were analyzed after 1 d, 1 wk, 1 and 6 mo of the procedure. When red spots on the esophageal varices were detected during endoscopy, the varices were considered to have aggravated and were treated endoscopically as soon as possible. The survival follow-up period was measured as the number of days from the date when interventional embolotherapy was performed until the date of the patient’s death or the most recent clinical visit.

The cumulative survival rate and the nontreatment rate of esophageal varices were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the values were compared by means of the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Statistical software (Statview version 5.0; SAS Institute, North Carolina, USA) was used for statistical analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The mean observation period was 966 ± 677 d. The mean duration of hospitalization for the treatment of the gastric varices was 17 d. According to the treatment algorithm, the BRTO, PTO, and combined therapy were angiographically successful in 81% (75/93), 44% (8/18), and 100% (10/10) patients, respectively. The three-tiered treatment strategy used in this study enabled successful treatment of all the gastric fundal varices. In 68 of the 75 (91%) patients in the BRTO group, the gastric varices were completely thrombosed; this was shown by the CT that was performed 1 wk after the initial BRTO. The remaining 7 (9%) patients who showed no improvement in the gastric varices, as indicated by CT, underwent an additional BRTO procedure. The BRTO procedure was performed twice on 5 patients, and three times on 2 patients with large gastric varices and dilated collateral veins. The overall BRTO technical success rate was 89% (68/75 + 5/7 + 2/2 = 75/84). In 18 patients who underwent variceal embolization by PTO alone or combined with BRTO, CT examination revealed that total obliteration of the gastric varices was achieved in all patients 1 wk after the initial procedure. According to the definition of technical success, the success rate was 91%, 100% and 100% in the BRTO, PTO and combined therapy.

During the follow-up period, recurrence of gastric varices was found in 3 patients (4%) in the BRTO group (1939, 1067, and 723 d after the BRTO procedure) and in 3 patients (38%) in the PTO group (1123, 574, and 150 d after the PTO procedure). In 3 patients in the BRTO group, the GOV2 type of recurrent gastric varices occurred after treatment of IGV1 with the BRTO procedure. Among the 3 patients in the PTO group, 2 had gastric varices of the GOV2 type, while 1 had gastric varices of the IGV1 type before the PTO procedure. In these 3 patients, the type of recurrent gastric varices was identical to those found prior to the PTO treatment. These recurrent gastric varices were strictly followed up without additional treatment. No variceal recurrence was found in the combined therapy group (Table 2).

| Results | BRTO | PTO | Com-T | Total | ||||

| Complete disappearance of gastric varices | 75 | 8 | 10 | 93 | ||||

| Variceal rebleeding | 1 | (1) | 1 | (13) | 0 | 2 | (2) | |

| Recurrence of gastric varices | 3 | (4) | 3 | (38) | 0 | 6 | (7) | |

| Aggravation of esophageal varices | 27 | (36) | 3 | (38) | 3 | (30) | 33 | (36) |

| Death | 21 | (28) | 0 | 2 | (30) | 23 | (25) | |

| Cause of death | ||||||||

| Hepatic failure | 8 | (11) | 0 | 1 | (10) | 9 | (10) | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 8 | (11) | 0 | 0 | 8 | (9) | ||

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 2 | (3) | 0 | 0 | 2 | (2) | ||

| Renal failure | 2 | (3) | 0 | 0 | 2 | (2) | ||

| Pneumonia | 1 | (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | (1) | ||

| Psychosis | 0 | 0 | 1 | (10) | 1 | (1) | ||

Rebleeding was observed in 2 patients after treatment (1 patient had received the BRTO procedure and the other had received the PTO treatment). In 1 patient in the BRTO group, rebleeding from gastric varices was observed before the additional BRTO procedure because of incomplete obliteration of the varices by the initial treatment. The gastric varices of the patient were obliterated by the second BRTO procedure. In 1 of the 3 patients who had been noted to have recurrent gastric varices in the PTO group, the rebleeding occurred due to the recurrence. The patient refused additional interventional embolotherapy and underwent Hassab’s devascularization after initial hemostasis by an endoscopic procedure[16]. In the combined group, no rebleeding was found.

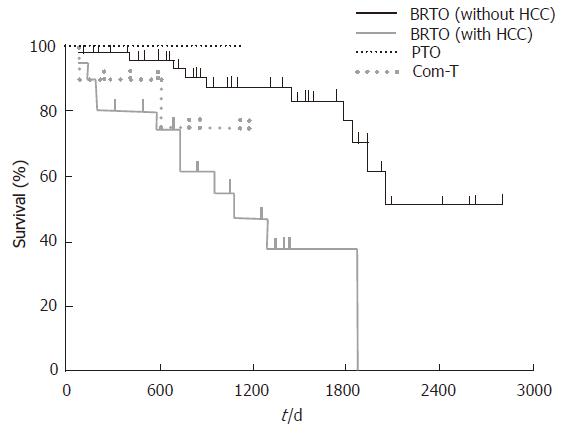

After the BRTO procedure, the 1- and 3-year survival rates were 92% and 75%, respectively. The 1- and 3-year survival rates were 98% and 87% in the patients without HCC in the BRTO group, 100% and 100% in the PTO group, and 90% and 75% in the combined therapy group, respectively. There was no significant difference across the three groups. On the other hand, the 1- and 3-year survival rates were 80% and 47% in the patients with HCC in the BRTO group. The survival rate after the BRTO procedure was significantly higher in the patients without HCC than in those with HCC (P < 0.01, Figure 3).

During the follow-up period, 21 patients in the BRTO group and 2 patients in the combined therapy group died; however, no patients in the PTO group died. Death due to hepatic failure occurred in the case of 8 (11%) patients in the BRTO group (range, 91-2056 d; median, 743 d) and 1 (10%) patient in the combined therapy group (605 d after the procedure). No significant difference was observed among the three procedures. The other causes of death in the BRTO group were hepatocellular carcinoma, cerebral hemorrhage, renal failure (due to diabetes mellitus), and pneumonia. In the combined therapy group, 1 patient died from psychosis 83 d after the procedure (Table 2).

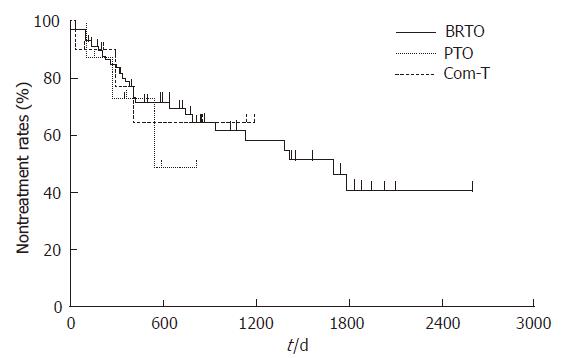

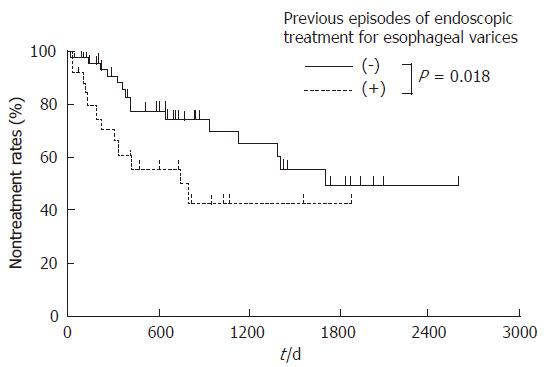

All three procedures caused adverse effects, such as fever (> 38.0°C), hemoglobinuria, abdominal pain, chest pain, nausea, and blood pressure elevation. On the other hand, ascites, pleural effusion, headache, and hepatic encephalopathy were detected in the BRTO group. No fatal complications were observed (Table 3). We have reported the change in the hepatic and renal function tests in patients treated with the BRTO procedure[17]. In terms of laboratory data, there was no difference in the three procedures. The esophageal varices aggravated in 27 (36%) patients in the BRTO group and in 3 patients in each of the PTO (38%) and combined therapy groups (33%). These were treated using the usual methods of EVL and EIS. During the course after the procedures, the cumulative nontreatment rates of esophageal varices at 1 year were 79%, 73%, and 77% in the BRTO, PTO, and combined therapy groups, respectively. There was no significant difference in the three procedures (Figure 4). The nontreatment rates of esophageal varices in the BRTO group at 1 and 3 year were 61% and 42% in the patients with esophageal varices and 86% and 70% in the patients without them prior to BRTO, respectively. The cumulative nontreatment rates of esophageal varices in the BRTO group were significantly lower in the patients with esophageal varices than in the patients without them prior to BRTO (P < 0.01, Figure 5).

| Complication | BRTO | PTO | Com-T | Total | ||||

| Fever | 47 | (63) | 4 | (50) | 9 | (90) | 60 | (65) |

| Hemoglobinuria | 35 | (47) | 3 | (38) | 10 | (100) | 48 | (52) |

| Abdominal pain | 48 | (64) | 6 | (75) | 7 | (70) | 66 | (71) |

| Nausea | 31 | (41) | 4 | (50) | 6 | (60) | 41 | (44) |

| Blood pressure elevation1 | 22 | (29) | 2 | (25) | 4 | (40) | 28 | (30) |

| Ascites | 3 | (4) | 0 | 0 | 3 | (3) | ||

| Pleural effusion | 5 | (7) | 0 | 0 | 5 | (5) | ||

| Headache | 6 | (8) | 0 | 0 | 6 | (7) | ||

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1 | (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | (1) | ||

| Chest pain | 24 | (32) | 2 | (25) | 7 | (70) | 33 | (36) |

Since Kanagawa et al[18] reported the treatment of gastric varices by BRTO with 50 g/L EOI, BRTO has been widely accepted as an interventional embolotherapy for gastric varices in Japan. Subsequently, many reports demonstrated the clinical efficacy and safety of this treatment[6-9]. According to several reports, the therapeutic result obtained by this treatment is satisfactory and the recurrence rate is very low. In our study, the BRTO procedure was angiographically successful in 81% (75/93) patients; hence, our results are consistent with those reported previously[9,10,19]. Recurrence of gastric varices was found in only 3 of the 75 patients who had undergone the BRTO procedure. In all 3 patients, the GOV2 type of recurrent gastric varices occurred after treatment of IGV1 with the BRTO procedure. Gastric varices that are classified as GOV2 have a direct connection with the coronary vein and esophageal varices. The aggravation of esophageal varices caused by damage of portal hemodynamics after the BRTO procedure has been well documented. It appeared that the mechanism of these recurrent gastric varices was similar to that observed in the aggravation of esophageal varices.

The BRTO procedure is applied to gastric varices that have a portosystemic shunt route to the inferior vena cava. Some gastric varices without a major shunt or those with many small collateral circulations are difficult to treat by the BRTO procedure. Reports of the refractory varices treated with the BRTO procedure are rare[10,20,21]. Thus, an adequate treatment strategy for refractory gastric varices has not yet been established. We performed the PTO procedure for uncontrollable gastric varices treated by the BRTO procedure. The first report on the treatment of gastric varices by the PTO procedure was described by Scott et al in 1976[15]. Since the previously used PTO procedure could obliterate inflow vessels but could not easily obliterate gastric varices completely, it was associated with a high incidence of rebleeding and recurrences. Our PTO procedure would fill the lumen of the gastric varices with the sclerotic agent in an antegrade manner by stopping the inflow into varices using coils and a balloon catheter that is wedged in an antegrade manner. EO, an anionic surfactant, infiltrates and destroys the cell membrane of venous endothelial cells. Damage to the venous endothelium caused by EO is greater than that caused by a 50% glucose solution. Therefore, EO causes thrombus formation in gastric varices, and gastric varices thrombosed by EO have been reported to be completely disappeared[6-9]. The PTO procedure that we used is the same as BRTO in that the gastric varices are thrombosed.

In this study, the PTO procedure rescued only 44% (8/18) patients who had uncontrollable gastric varices treated by the BRTO procedure. To block the gastric variceal blood flow, the PTO procedure, which involves the catheterization of the only feeding vein, may be less effective than the combined therapy. It is probable that the antegrade procedure could obliterate the feeding vein but could not completely and easily obliterate the varices with a large draining vein. The patients in the PTO group had more minor collateral circulation, such as pericardial or hemiazygous veins, as compared with the patients in the BRTO group.

The indication for the PTO procedure with 50 g/dL EOI was the presence of gastric varices without large draining veins and varices untreated by BRTO because of many small collateral veins. In the PTO group, the gastric varices recurred in 3 patients with incomplete eradication; bleeding occurred in 1 of these patients. It appeared that the therapeutic efficacy of the PTO procedure was incomplete for uncontrollable gastric varices treated by the BRTO procedure.

Some of the patients who underwent attempted BRTO had no embolization performed at all via antegrade route because of unfavorable anatomy whilst others had some embolization with coils and/or sclerosant. We performed the combined BRTO and PTO therapy on patients in whom uncontrollable gastric varices had been treated by the BRTO procedure and the PTO procedure. Reports on the varices that had been treated with combined therapy, which obstructs both the feeding and the draining veins of the varices, are rare. Kimura et al[22] reported a case of rectal varices that was treated with double balloon-occluded embolotherapy in 1997. Similarly, Ota et al[23] reported the results of combined therapy comprising BRTO and transileocolic vein obliteration (TIO) in a patient with duodenal varices. Kiyosue et al[24] suggested that the indication for combined therapy was the presence of gastric varices that are supplied by single or multiple gastric veins with coexistent gastric veins that are directly contiguous with the shunt but do not contribute to the varices. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies on the treatment of gastric varices by combined BRTO and PTO therapy. In our study, the therapeutic result of the combined therapy was satisfactory. No bleeding or variceal recurrence was found in the combined therapy group.

Combined therapy, which can obstruct both the feeding and the draining veins of gastric varices to retain the sclerosing agent completely in the varices, may provide a better control of the gastric variceal blood flow than that provided by the only BRTO or PTO procedure. Our study demonstrates that combined therapy is very effective in the treatment of gastric varices, irrespective of whether patients have had a large gastrorenal shunt and/or collateral circulation. Since the combined therapy may eliminate the hemodynamics of gastric varices, this procedure may be more effective than other procedures. In fact, the obliteration of the gastric varices by this method was successful in all 10 patients in whom the BRTO or PTO procedure was unsuccessfully performed.

Although only the femoral or internal jugular vein is punctured in the BRTO procedure, the combined therapy or the PTO procedure requires a puncture in the liver. Therefore, the BRTO procedure is less invasive than the other procedures. Since the combined therapy appears to be similar to the BRTO procedure in terms of safety and efficacy, we propose that the BRTO procedure should be the first choice of the treatment for gastric varices. The combined therapy should only be performed in the case of highly selected patients. We believe that the indication for combined therapy is refractory gastric varices that remain untreated despite being subjected to the BRTO and PTO procedures. In addition, the PTO procedure is less invasive than the combined therapy, because the femoral or internal jugular vein is not punctured in this procedure. Thus, the results presented here indicate that the algorithmic strategy for treating gastric varices using the BRTO and PTO procedures and the combined therapy is feasible (Figure 1).

These three procedures for obliterating the gastric varices may increase the portal pressure. Aggravation of the esophageal by these treatments varices was recognized to be a result of elevated portal pressure. From the viewpoint of aggravation of esophageal varices, no statistical differences were demonstrated among the three procedures. However, non-treatment rate of esophageal varices after the BRTO was significantly lower in those who were treated esophageal varices before BRTO than those not treated. Our results are consistent with those reported earlier[19]. Periodic endoscopic follow-up is recommended after the eradication of gastric varices, particularly in patients with esophageal varices prior to the BRTO procedure. The mortality rate for gastric variceal bleeding is much higher than that for esophageal variceal bleeding[25]. Therefore, we believe that these changes in the portal hemodynamics were preferable because esophageal varices can be easily controlled by endoscopic therapy.

In conclusion, combined BRTO and PTO therapy may rescue cases with uncontrollable gastric fundal varices that remained even after treatment with BRTO and/or PTO. Our study could establish the algorithmic strategy for treating gastric fundal varices using interventional embolotherapy. However, there were limitations of our study, including retrospective nature and discrepancy in sample size between the BRTO, PTO and combined therapy groups. Further, long-term prospective studies would assist in clarifying the effect of combined BRTO and PTO therapy.

S- Editor Pan BR L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Bai SH

| 1. | Rössle M, Haag K, Ochs A, Sellinger M, Nöldge G, Perarnau JM, Berger E, Blum U, Gabelmann A, Hauenstein K. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 481] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | LaBerge JM, Somberg KA, Lake JR, Gordon RL, Kerlan RK Jr, Ascher NL, Roberts JP, Simor MM, Doherty CA, Hahn J. Two-year outcome following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for variceal bleeding: results in 90 patients. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1143-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Albillos A, Ruiz del Arbol L. "Salvage" transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: gastric fundal compared with esophageal variceal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:294-295. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Barange K, Péron JM, Imani K, Otal P, Payen JL, Rousseau H, Pascal JP, Joffre F, Vinel JP. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the treatment of refractory bleeding from ruptured gastric varices. Hepatology. 1999;30:1139-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rees CJ, Nylander DL, Thompson NP, Rose JD, Record CO, Hudson M. Do gastric and oesophageal varices bleed at different portal pressures and is TIPS an effective treatment. Liver. 2000;20:253-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hirota S, Matsumoto S, Tomita M, Sako M, Kono M. Retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices. Radiology. 1999;211:349-356. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Fukuda T, Hirota S, Sugimura K. Long-term results of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for the treatment of gastric varices and hepatic encephalopathy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:327-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chikamori F, Kuniyoshi N, Shibuya S, Takase Y. Eight years of experience with transjugular retrograde obliteration for gastric varices with gastrorenal shunts. Surgery. 2001;129:414-420. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kitamoto M, Imamura M, Kamada K, Aikata H, Kawakami Y, Matsumoto A, Kurihara Y, Kono H, Shirakawa H, Nakanishi T. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric fundal varices with hemorrhage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1167-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ninoi T, Nakamura K, Kaminou T, Nishida N, Sakai Y, Kitayama T, Hamuro M, Yamada R, Arakawa T, Inoue Y. TIPS versus transcatheter sclerotherapy for gastric varices. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:369-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5490] [Cited by in RCA: 5812] [Article Influence: 109.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Chikamori F, Kuniyoshi N, Shibuya S, Takase Y. Short-term hemodynamic effects of transjugular retrograde obliteration of gastric varices with gastrorenal shunt. Dig Surg. 2000;17:332-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 870] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (42)] |

| 14. | Sarin SK, Kumar A. Gastric varices: profile, classification, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1244-1249. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Scott J, Dick R, Long RG, Sherlock S. Percutaneous transhepatic obliteration of gastro-oesophageal varices. Lancet. 1976;2:53-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hassab MA. Gastroesophageal decongestion and splenectomy in the treatment of esophageal varices in bilharzial cirrhosis: further studies with a report on 355 operations. Surgery. 1967;61:169-176. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Shimoda R, Horiuchi K, Hagiwara S, Suzuki H, Yamazaki Y, Kosone T, Ichikawa T, Arai H, Yamada T, Abe T. Short-term complications of retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices in patients with portal hypertension: effects of obliteration of major portosystemic shunts. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:306-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kanagawa H, Mima S, Kouyama H, Gotoh K, Uchida T, Okuda K. Treatment of gastric fundal varices by balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ninoi T, Nishida N, Kaminou T, Sakai Y, Kitayama T, Hamuro M, Yamada R, Nakamura K, Arakawa T, Inoue Y. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices with gastrorenal shunt: long-term follow-up in 78 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1340-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Koito K, Namieno T, Nagakawa T, Morita K. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric varices with gastrorenal or gastrocaval collaterals. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1317-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ibukuro K, Mori K, Tsukiyama T, Inoue Y, Iwamoto Y, Tagawa K. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varix draining via the left inferior phrenic vein into the left hepatic vein. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1999;22:415-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kimura T, Haruta I, Isobe Y, Ueno E, Toda J, Nemoto Y, Ishikawa K, Miyazono Y, Shimizu K, Yamauchi K. A novel therapeutic approach for rectal varices: a case report of rectal varices treated with double balloon-occluded embolotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:883-886. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Ota K, Okazaki M, Higashihara H, Kokawa H, Shirai Z, Anan A, Kitamura Y, Shijo H. Combination of transileocolic vein obliteration and balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration is effective for ruptured duodenal varices. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:694-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kiyosue H, Mori H, Matsumoto S, Yamada Y, Hori Y, Okino Y. Transcatheter obliteration of gastric varices: Part 2. Strategy and techniques based on hemodynamic features. Radiographics. 2003;23:921-937; discussion 937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Greig JD, Garden OJ, Anderson JR, Carter DC. Management of gastric variceal haemorrhage. Br J Surg. 1990;77:297-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |