INTRODUCTION

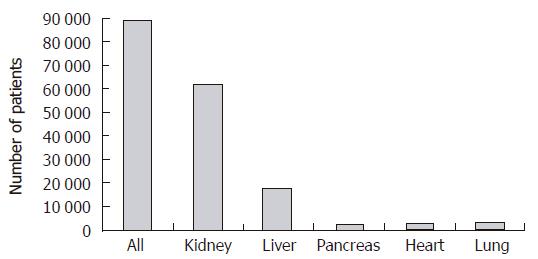

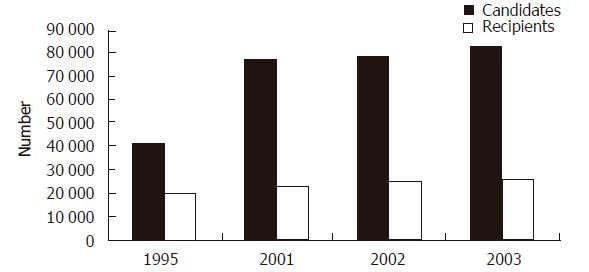

The field of solid organ transplantation has made dramatic improvements to the overall health of patients suffering from end-stage organ failure. The ability to provide successful organ replacement is a testament to the progress made in the development of modern immunosuppression and the refinements made in the surgical management of these patients. The subsequent expansion of solid organ transplantation is depicted in Figure 1 which demonstrates that currently more than 90 000 patients are awaiting some form of solid organ transplant in the United States. Unfortunately, this rapid success in organ transplantation has not been matched by a parallel increase in the supply of organs available for transplant. Figure 2 demonstrates this graphically, where the additions to the waiting list continue to increase in a nonlinear fashion while the number of recipients receiving organ transplants has increased little in the last five years. The disparity between individuals awaiting organ transplantation and the supply of transplantable organs is the single largest impediment to application of successful organ transplantation for patients suffering end-stage organ failure.

Figure 2 Growth of the number of candidates for transplantation compared to the number of recipients.

(http://www.optn.org)

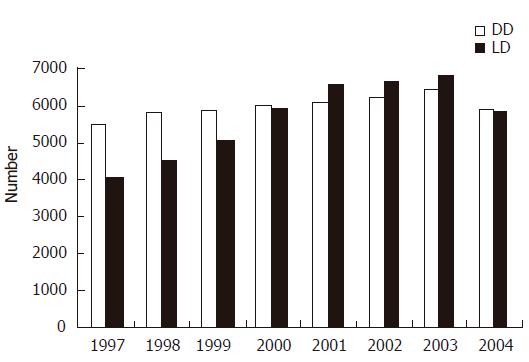

One of the major ways transplant centers have attempted to increase the number of transplants performed is through increasing the numbers of living donors. Analysis of the types of organs used in organ transplantation shows that the year 2001 marks a significant shift to living donors. Figure 3 demonstrates in the year 2001, living donors were used more often as a source for kidney transplantation than were deceased donors. Analysis within the deceased donor pool reveals that as the median age of the donors has increased and as the severity of illness amongst the donors has increased, the use of marginal donors has played a greater role in supplying organs for transplantation. As the disparity between need and supply continues to widen, there are increasing pressures to seek alternative methods to supply organ donors to meet this crisis. An analysis of this disparity can most readily be divided between those issues that impact recipients directly and those that impact the number, type and quality of donors. With respect to recipients, the disparity between those listed and those transplanted can be regulated by imposing restrictions on the indications for transplantation. This, however, would be socially unacceptable as it is essentially withholding life-saving therapy. Another avenue to narrow the gap between those waiting for transplant and the supply of transplantable organs would be a change in the allocation policy. While allocation strategies continue to be modified within the organ groups (kidney, liver, pancreas, lung, heart) the intent of the new allocation strategies is to supply organs to those patients in the greatest need. The unwillingness to restrict the indications and the allocation of organs, demonstrates that society and the medial community will continue to broaden the inclusion criteria for patients who will benefit from transplantation. Surgical and immunosuppressive advances have markedly improved survival of all types of grafts of the past decade. From 1993 to 2002, the one-year graft survival of deceased donor kidneys improved from 82.1% to 89%, while live donor kidney grafts improved from a 91.4% to 95% 1-yr graft survival[1]. During this same time frame, pancreas grafts demonstrated improvement from 78.0% to 86.2%, while deceased donor liver grafts showed increases in graft survival from 73.9% to 82.4%. This continued growth in including more recipients is no doubt fueled by the success of transplant, both in quality of life and duration of life obtained.

Figure 3 Comparisons of the number of transplants from deceased donors (DD) and living donors (LD).

(http://www.optn.org)

EMERGENCE OF THE EXPANDED DONOR

Within the deceased donor category there are two broad distinctions of donor types. Those donors being designated as brain dead donors and donors designated as donation after cardiac death. The criteria for the diagnosis for brain death was established in 1968 by a NIH sponsored gathering of professionals. Documents coming out of this meeting, designated as the Harvard Brain Death Criteria[2], were instrumental in establishing brain death as medical and legal criteria to allow withdrawal of life support. At the time of this conference, there were many individuals being sustained on life support in intensive care units throughout the United States with no hope of recovery. This allocation of scarce ICU beds was negatively impacting the delivery of health care throughout the country. The establishment and acceptance of brain death criteria provided a legal, ethical and medical basis for the withdrawal of life support from these non-salvageable patients. It is from this pool that the majority of organ donors within the United States have been supplied. Although brain death criteria is accepted in North America, within other hemispheres, (i.e. Asia), brain death criteria has not been accepted due to religious and social beliefs. The efforts in the United States to increase the numbers of deceased donors have been varied and include public service announcements, education and legal mandates administered through regulatory agencies of health care within the United States. Despite these efforts, the conversion rate of deceased donors is below predicted values. However, even if all potential deceased donors were converted for donation, their numbers would be inadequate to supply enough organs for the increasing number of patients awaiting transplant[3]. Consequently, although a tremendous amount of resources have been applied to increasing the conversion rate within potential brain dead donors, the deceased donor pool would fall short of satisfying the disparity between those in need and awaiting solid organ transplantation. As a consequence, increasing the numbers of deceased donors have resulted in expansion of donation after cardiac death. Prior to the establishment of brain death criteria, the only deceased donors used for transplantation came from donation after cardiac death category. Though not formally recognized as such, donors after cardiac death should be considered to be a member of the expanded donor pool. Expanded donors are defined as organs that carry additional risks for transplantation beyond those associated with the standard transplant procedure[4]. This group of patients is typically composed of critically ill patients with no expectation of neurological recovery, in whom the decision to withdraw life support has been made. Within this group, various protocols have been applied to establish usability of the potential grafts[5]. Many organ procurement organizations throughout the United States have undertaken initiatives to increase the number of organs retrieved from this class of donor. Although acceptable within the defined limits for kidney transplantation[6], this category of donor represents significant risks when applied to liver transplantation, specifically that of biliary complications and hepatic artery stenosis[7]. Despite the medical, legal and ethical justification for this procedure it is still shrouded in an era of suspicion by many members of the lay public and medical community. The suspicions rest with the perception that patients are prematurely withdrawn from life support to supply organs for transplantation. While the use of deceased donors from brain dead patients is considered standard of care within the transplant community, utilization of expanded donors has been evolving.

Within the specialty of kidney transplantation, a formalized definition of the expanded donor has been proposed (UNOS policy 3.5.1)[8]. This category of brain dead donor may carry the potential of increased risk of graft dysfunction and shortened graft survival; however, use of these kidneys would augment the current short supply of kidneys used for transplant and may appropriately serve the needs of recipients who otherwise would not be transplanted. Expanded donor kidneys, as defined by UNOS, are primarily all donors greater than 60 years of age or donors greater than 50 years of age who have co-morbidities of hypertension, cerebral vascular accident as a cause of death or creatinine elevation greater than 1.5. Institution of expanded donor utilization requires: definition of the expanded donor graft, identification of recipients who have given informed consent to be recipients of an expanded donor graft, and expedited placement of these kidney grafts to lessen the deleterious effects of cold storage time. Medical and ethical justifications for use of these expanded donors comes from analysis of SRTR (Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients) data demonstrating that the relative mortality risk within the population of dialysis patients is lower with the use of an expanded donor kidney compared to remaining on dialysis at approximately 182 d after successful transplant and continues to have a survival advantage as long as the graft continues to work. What defines an expanded donor within the deceased donor liver grafts has been more difficult and currently there is no consensus. Within the deceased donor category, criteria such as age, infection, anatomic anomalies, presence of malignancies and steatosis carry with them added risk of liver transplants. Non-heart beating donor grafts derived from donation after cardiac death and livers that have been acquired through split procedures appear to have similar graft survival rates as standard deceased donor grafts, however, they are associated with more long-term complications[7,9]. Despite the obscurity of a true definition of expanded donor within the liver transplant community, many of these grafts are likely to expose the recipient to increased short term risk, including death, and may also result in more long term risks compared to standard liver grafts[10]. The balance, however, rests in the fact that increased waiting times are associated with increased mortality risks of those patients awaiting liver transplantation. It has been demonstrated by population analysis that the sickest patients awaiting liver transplantation do derive a survival benefit from transplantation with essentially any liver made available for transplantation[11]. Additionally, analysis of deceased donor liver grafts from a mid-west OPO demonstrates that there are few “perfect livers” available for transplant and in fact the number of livers included in the “perfect” category represent less than 3% of the livers used for transplant during the study (unpublished observations). Therefore, due to this spectrum of quality among the livers being utilized for liver transplantation, which extends from perfect livers to expanded donor livers, to livers that are not usable, the majority of deceased donor organs used for transplant are less than optimal.

It is not surprising that expansion of inclusion criteria within the deceased donor pool to include riskier organs for transplant has also stimulated expansion within the living donor category. 1954 marks a historic event in human history. It was at that time, December 24, 1954, when the first successful organ transplant was performed. This was a kidney transplant performed in Boston between identical twins. The necessity for using a living donor at that time was to overcome the immunologic barrier to transplant. Through the use of an identical, living donor the deficiency in immunosuppression therapy did not result in graft loss or patient loss. The ethical dilemma at that time was substantial and continues today. For the first time in medical history a healthy, volunteer donor was subjected to real and significant harm (surgical removal of a kidney) to provide benefit for another individual. Clearly this activity appears to violate the first rule of medicine primum non nocere. The justification for exposing the living donor to real and significant risks was balanced by the fact that the recipient who suffered end-stage kidney failure had no acceptable treatment options available. The diagnosis of end-stage kidney failure at that time resulted in the certain death of patients, as dialysis therapy was not available. Additionally, previous kidney transplant attempts resulted in graft loss secondary to rejection, or patient loss secondary to infection. This was, as Francis Moore described, “a desperate case”. Additionally, legal intervention at the time justified exposure of the live donor as a trade-off in risks. Specifically, courts ruled that loss of an identical twin sibling would impose far more psychological harm and damage than would exposure to the risks associated with live donation. Since 1954, the inclusion criteria for acceptable, living donors has expanded. It has expanded with respect to organs being donated for transplantation as well as candidates being accepted for donation.

LIVING KIDNEY DONORS

Since 1954, the expansion of candidates deemed appropriate for living donation has moved beyond identical twins. With the development of effective immunosuppressive therapy, genetic identity is no longer required for successful transplant. This expansion began with genetically related donors, siblings or parents to donors that had an emotional relationship with the recipient including spouse and significant others. The increased use of living donors in kidney transplantation (Figure 3) has been further supported by the relative safety of the operation. Published reports demonstrate a mortality risk of approximately 0.03% and a complication rate less than 3% when performed in high volume centers[12]. Additionally, surgical advances have improved the acceptance and willingness of living donation, as the movement from open nephrectomy to laparoscopic nephrectomy has demonstrated. Patients are more willing to undergo laparoscopic nephrectomy associated with earlier recovery and less pain associated with the donation. Analysis of population studies demonstrates that recipients of living donor grafts have decreased morbidity associated with transplant and an increase in patient and graft survival, as compared to deceased donor grafts. This improvement in survival of both patients and grafts is multifactorial and can be ascribed to earlier transplantation, limitation of cold ischemia time and transplantation with a better functioning graft. The most recent expansion of donor inclusion now includes directed, altruistic donation, non-directed anonymous donation and solicitation for donation. Directed, altruistic donation is usually provided by a donor who has a casual acquaintance relationship with the intended recipient. These donors usually originate from church groups, work organizations or other loose social associations. Because of the obvious benefits to the recipient and well defined and small risk to the donor, these donor-recipient pairs have been medically and ethically accepted by the transplant community. Further modifications of the living donor, recipient relationship include a swap donation between incompatible recipient donor pairs and other incompatible recipient donor pairs[13]. Previously, excluded groups have been the non-directed anonymous donors who now have become more acceptable within the transplant community. These donors are individuals who feel an overwhelming desire to donate a kidney to anyone on a transplant list for the sole purpose of improving their quality of life and longevity. This group was previously excluded on the basis of psychological instability; however, recent studies have demonstrated that although a significant portion of this group is excluded based on medical and psychosocial contraindications, there are individuals who are both psychiatrically and medically appropriate for donation[14]. Some programs have accepted these live donors for donation to patients on their transplant waiting list while others have accepted donation to the waiting list within the region. The most recent and unsettling practice within the living donor category has been outright solicitation for organ donation. This process most notably depicted through internet web sites appears to suffer from ethically questionable motives. In all forms of living donation the following practices exist. First, in directed donation, be it genetically related emotionally or casual acquaintance, there is a clear and definable benefit for which the donor can experience and value in the recipient. It appears that the risk benefit analysis under this relationship favors donation. In non-directed living donation, that being from a stranger or anonymous donor to either a transplant center waiting list or a regional waiting list, the benefit derived by the donor is in terms of a self-motivation and realization of doing a profoundly charitable and noble act for another human being. The benefit received by the recipient is obvious and the same for any recipient of living donor graft. Under this arrangement it appears that the risk benefit analysis would still favor the process of living donation. In both of these circumstances, the recipients participate in a well organized transparent and regulated system of valuation, regulation, allocation and access to the transplant graft. In the context of solicitation for donors, however, the emotional bond between donor and recipient pair is more difficult to define. The genetic bond is non-existent and motivations of pure altruism may take on a different a definition. Potential donors usually survey websites for the most compelling or set of characteristics that would satisfy their desire to donate. Reciepients have access in a non-equal way compared to other registered wait list recipients with UNOS. This injustice between access to secondary sources of organ allocation results in difficulties to delineate motives between donor and recipient pair, and provide the potential for exploitation of either or both participants in this enterprise, thus, making solicitation for living donation difficult to defend on ethical grounds. Donors are not prohibited from donating to the list in an anonymous fashion if altruism is their true motivation; however, recipients who undertake this process jump the queue among other recipients for access to this scarce resource. This unequal distribution of access undermines the trust and confidence of organ allocation within the US system.

LIVING LIVER DONORS

In the practice of liver transplantation, use of the living donor began as a case reports in the late 1989[15]. This was further studied in a prospective, comprehensive, IRB supported protocol at the University of Chicago[16], in which 20 donor-recipient pairs underwent transplantation. This study incorporated key components of the use of living donors, specifically; research ethics consultation, assignment of a donor advocate, demonstration of field strength of the institution and physician team prior to undertaking the study and a cooling off period with multiple steps in the informed consent process[17]. This landmark study in the use of living donors served to establish modifications in the living donor surgical procedure and facilitated incorporation and dissemination of the practice of living donor liver transplants for pediatric recipients world-wide. Justification for exposing donors to a potentially significant harm was offset by the dire circumstance of infants awaiting the liver transplant patient. Prior to institution of the living donor liver transplant procedure for infants, the mortality rates for infants awaiting liver transplantation approached 30%[18]. With the rapid acceptance of this surgical innovation, the mortality in some institutions performing pediatric liver transplantation diminished to less than 1%[19]. Throughout the study, the surgical techniques were modified and living donor liver transplantation for pediatric recipients has become standard of care worldwide. The estimated mortality risk for the donor is approximately 0.1%, with morbidity less than 15%[20]. It is important to note that within the use of living donors for pediatric liver transplantation, the majorities of donors are genetically or emotionally related to the recipient and include parents, siblings, aunts, uncles and grandparents.

Extension of living donor liver transplantation to adult recipients began in the late 90’s, from various institutions conducting independent small series[21,22]. Contrary to the pediatric experience, the introduction of adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation did not benefit from a prospective, well defined, single center study. In fact, the majority of institutions performing adult-to-adult living donor liver transplant did so without an accepted IRB protocol. Consequently the risks and benefits associated with the procedure were difficult to quantify and not applicable across programs. Donor deaths have occurred and it wasn’t until 2001 where the first widely publicized donor death stimulated regulatory intervention in New York State concerning adult to adult living donor liver transplantation[23,24]. Secondary to that well publicized complication, the numbers of adult-to-adult living donor liver transplants rapidly diminished within the United States, having only recently begun to increase[25]. Adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation is performed in many countries throughout the world and in particular serves as the only source of organs for transplantation in regions where religious opposition to deceased donation occur (i.e. Japan and China)[26]. Unfortunately, the development of the procedure has not clearly delineated indications and contraindications for both recipients and donors. This is a process which continues in evolution and is dependent upon reports from individual centers. There is currently an NIH sponsored multi-institutional trial collecting data which should be very important to help define the appropriate role and complications of adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation for both recipient and donors alike. Although the majority of donor-recipient pairs have both a genetic or emotional relationships justifying the risk/benefit of such a procedure, there has been increased inclusion of anonymous living donors and solicitation for living donors. In an operation whose mortality has been predicted between 0.6 and 1% and whose morbidity has ranged as high as 67% the donor population[27,28], it is difficult to ethically justify the undertaking of the riskiest live donor operation performed to date without understanding the benefit derived in the risk/benefit analysis. Living donation has also been applied to lung transplantation, although small in number it appears that well selected donors and recipient pairs result in an acceptable outcome justifying the exposure of the donor to this operation[29,30]. The relative safety to this operation is no doubt dependent upon the small number of centers who are engaged in this practice. With respect to living donor intestinal transplantation, it appears that in well controlled circumstances, when performed in experienced centers, this operation may be of benefit to recipients with acceptable risks to donors[31,32]. However, the number of cases remains small and the demonstration of an inadequate deceased donor supply have not fully justified exposure and utilization of the live donor for intestinal transplantation. Therefore, it is difficult at this time, outside of an experimental protocol, to ethically justify placing a donor at unknown risk for undergoing intestinal procurement for a unclear recipient benefit.

In conclusion, it is clear that as transplantation provides a successful treatment for a variety of diseases which result in end-organ failure and that the demand for organs will continue to out strip the supply. This disparity will continue to drive the practice of expanding the criteria for what is defined as an acceptable deceased donor or living donor. With respect to deceased donors, expansion of the inclusion criteria can only be accomplished at the margins currently defined as expanded donor criteria. Utilization of these grafts does result in added risks experienced by the recipient. It is imperative that these added risks associated with the use of expanded, deceased donor grafts are appropriately matched to the expected outcomes in the recipients for whom they are used. Specifically, it would not be ethically acceptable to use a 70 year old kidney in a 16 year old recipient unless there were significant and compelling reason to expose such a recipient to the risks and limited survival of such a graft. Additionally, it may not be acceptable to utilize a 21 year old perfect kidney in transplantation of a 75 year old recipient with multiple medical problems who has an expected life expectancy of less than 3 years. These are difficult decisions which have not been codified into practice plans currently. With respect living donor use for kidney transplantation, it appears that our current dilemma rests in the use of living donor grafts procured from solicited donors. The risk/benefit analysis has always favored performance of a relatively safe nephrectomy for the demonstrable benefits in the transplant recipient. This risk/benefit relationship has always been solidified and enriched by a donor-recipient relationship; be it genetic, emotional or acquaintance. In liver transplantation, it appears that until such time when reliable indicators exist to exclude expanded donor grafts, the survival advantage with transplantation continues to be a compelling argument in favor their use. In the field of living donor liver transplantation, adult-to-pediatric transplantation has been incorporated as standard of care in pediatric liver transplantation. Within the adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation procedure, the extent of the donor operation, inclusion and exclusion of donor candidates, and inclusion and exclusion of recipients continue to require delineation. Under the current practice it appears that more formalized, investigation and study would be required to protect both recipient and donor pairs and to define, clearly, the indications and contraindications of adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. With respect to the use of all living donors, informed consent, donor follow up, and protection of donors, should be paramount in institutions undertaking this enterprise.

S- Editor Pan BR E- Editor Bai SH