GERD

In 1956, Nissen[1] was the first surgeon to treat severe GERD by wrapping the gastric fundus around the distal esophagus. The Nissen fundoplication rapidly became the standard for the surgical management of GERD.

Dallemagne et al[2] performed the first laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in Belgium in 1991. After quickly establishing the safety and efficacy of the procedure, laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS) became the state of the art surgical treatment for GERD.

With increased experience and improvements of advanced laparoscopic and esophageal surgical skills, there has been a significant decline in early and long-term complications. In a review of more than 10 000 reported laparoscopic antireflux procedures, morbidity was uncommon (6%), mortality was rare (0.08%), and the reoperation rate was low (4%)[3]. The overall mortality rate is generally low, but does depend on the experience of the surgeon. The rate decreases from 1.3% with an experience of less than 5 cases, to 0.0% with 50 cases or more[4]. The most common side effects of LARS are dysphagia and bloating, but these symptoms are usually self-limited. Dysphagia, for example, is common in the immediate post-operative period, but usually resolves in the first six weeks after surgery; persistent dysphagia occurs in only 2% to 5% of patients[5]. The symptom of bloating also seems overemphasized as a surgical side effect because the prevalence of bloating is quite similar in both surgically and medically treated patients[6].

Although the ultimate goal of both medical and surgical therapy is the alleviation of symptoms, surgical therapy imparts a mechanical solution to GERD whereas medical therapy is aimed at acid suppression. Despite the disparate mechanisms of action, comparisons of medical and surgical therapy of GERD enliven gastroenterologists and surgeons alike. Additional debate concerns the effectiveness of LARS to reverse reflux related injury (e.g., Barrett’s esophagus) or alleviate chronic respiratory disease. Finally, technical considerations of LARS, such as the utility of partial or complete fundoplication or the necessity to divide the short gastric vessels, have yet to be completely reconciled.

Medication vs operation

Antireflux surgery has been shown to be very effective at alleviating symptoms in 88% to 95% of patients, with excellent patient satisfaction, in both short and long term studies[7-9]. These excellent results include patients with complicated GERD, such as those with large hiatal hernias, refractory esophagitis and peptic strictures. In addition to symptomatic improvement, the effectiveness of LARS has been objectively confirmed with 24-h pH monitoring, which clearly demonstrates excellent control of esophageal acid exposure more than five years after surgery[8]. When compared to medical therapy, surgical therapy has proven to be superior. A randomized, multicenter trial, with 5-year follow-up, demonstrated that antireflux surgery (open fundoplication) is more effective than proton pump inhibition (PPI) in controlling gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms[7,10].

Another randomized trial, with 10 year follow-up, evaluating the effectiveness of medical therapy (omeprazole) versus antireflux surgery found that patients who underwent surgery had improved relief of symptoms when compared to the medically treated group[11]. Proponents of medical therapy argue that 60% of patients in the surgical group were taking antacids on a regular basis and should therefore be considered treatment failures. However, the liberal use of antacids in medical practice today makes medication use an unreliable outcome measure of LARS. This is supported by the fact that up to 75% of patients who take such medications after Nissen fundoplication have normal 24-h pH results when tested[12].

Barrett’s esophagus

Barrett’s esophagus, defined microscopically as intestinal metaplasia of the lower esophageal epithelium, is a result of severe GERD, and carries with it an increased risk of progression to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Many patients with Barrett’s epithelium have GERD symptoms that are difficult to control with medical therapy, and there is little evidence that the natural history of Barrett’s can be affected by proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Oelschlager et al[13] recently reported excellent control of reflux and associated symptoms after LARS in patients with Barrett’s

esophagus. Complete regression was demonstrated in 34 of 106 (32%) patients with intestinal metaplasia, and in 55% of those with short segments (< 3 cm) of Barrett’s

esophagus. Hofstetter et al[14] observed that low-grade dysplasia regressed to nondysplastic Barrett’s in 7 of 16 (44%) patients, and in 9 of 63 (14%) intestinal metaplasia regressed to cardiac mucosa.

Additionally, Bowers et al[15] reported a regression rate of 13 of 22 (59%) of patients with short segments of Barrett’s. With more and more evidence suggesting that LARS may affect the natural history of Barrett’s esophagus, and ultimately the risk of esophageal cancer, surgical therapy should be strongly considered for patients with Barrett’s esophagus, especially for young patients and those with symptomatic Barrett’s esophagus.

Respiratory symptoms

GERD has long been associated with respiratory symptoms (chronic cough, sinusitis, and recurrent pneumonia), asthma and laryngeal injury (hoarseness, subglottic stenosis, and laryngeal cancer)[16]. A leading theory suggests that decreased esophageal peristalsis and delayed acid clearance leads to persistent aspiration and subsequently to injury within the respiratory tract. Respiratory complaints in patients with GERD are synonymously referred to as atypical symptoms of GERD, laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), or laryngoesophageal reflux disease (LERD). And even though atypical GERD symptoms are much more likely to respond to surgical therapy than medical therapy, the most useful predictor for the relief of reflux-related respiratory symptoms through LARS is a prior positive response to PPI therapy[17].

Johnson et al[18] found that patients with typical symptoms of GERD frequently have respiratory symptoms. In their series of patients undergoing Nissen fundoplication for typical symptoms of GERD, 76% of patients who had respiratory symptoms preoperatively, experienced relief of their symptoms postoperatively. Similarly, Farrell et al[19] reported on 324 patients who underwent laparoscopic fundoplication for typical and atypical symptoms of GERD. They found that 99% of patients with predominantly typical symptoms experienced symptom relief, whereas 93% of those with primarily atypical symptoms (asthma, cough, and hoarseness) experienced relief. Recently, it has become increasingly evident that GERD can be associated with non-allergic asthma. Spivak et al[20] reported significantly improved asthma symptoms for 39 patients who underwent antireflux surgery for the primary indication of asthma associated with GERD.

Total vs partial fundoplication

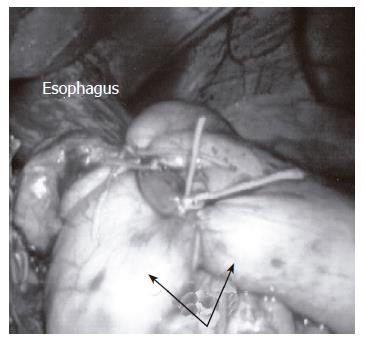

The total (Nissen) fundoplication involves a 360-degree wrap of the gastric fundus around the esophagus (Figure 1) and is the most commonly performed anti-reflux operation. Further insight into esophageal motility disorders and concerns of postoperative dysphagia has prompted the discussion whether the total or partial fundoplication is more appropriate treatment for GERD. Total wrap supporters acknowledge the fact that the wrap needs to be “floppy” to minimize postoperative dysphagia. It should also be noted that a floppy Nissen fundoplication is safe and effective in patients suffering from a defective esophageal peristalsis. Finally, proponents of the total fundoplication note the decreased the effectiveness of a partial fundoplication in controlling reflux.

Figure 1 The Nissen fundoplication involves a 360-degree wrap (arrows) of the gastric fundus around the distal esophagus.

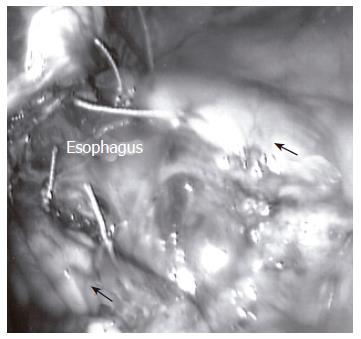

Two partial fundoplications are in common practice; they are the Dor and Toupet fundoplications. Of these two partial wraps, the Toupet is the most commonly performed partial fundoplication (Figure 2). Fibbe et al[21] compared laparoscopic partial and total fundoplications in 200 patients with esophageal motility disorders and found no difference in postoperative recurrence of reflux and concluded that no tailoring of the surgical management is necessary. Similarly, Laws et al[22] found no clear advantage of one wrap over the other in their prospective, randomized study comparing these two groups. Moreover, in a meta-analysis of 9 prospective randomized trials including open and laparoscopic total vs partial fundoplications in 793 patients, no statistical difference was found in new-onset dysphagia or recurrence of reflux[23].

Figure 2 With the Toupet fundoplication, the gastric fundus (arrows) is incompletely wrapped around the posterior, distal esophagus.

Dividing the short gastric vessels

The effect of fundic mobilization has been discussed widely in the surgical community. A meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials found that the operative time is slightly, but not significantly longer when the superior-most short gastric vessels are divided[23]. No significant differences were found regarding the incidence of postoperative dysphagia or complications by dividing the short gastric vessels. The authors of this review favor the complete mobilization of the gastric fundus with division of the short gastric vessels because it is usually necessary for the creation of a “floppy” fundoplication.

Endoluminal therapy

Recent interest in the development in endoluminal therapy has led to new alternatives in the treatment of GERD. These treatment modalities are primarily designed for patients with little or no significant hiatal hernia. These therapies are delivered trans-orally, via upper endoscopy. There are principally three different types of these new treatment options. First, radiofrequency energy delivered to the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) theoretically adds bulk to the LES and changes the sphincter’s compliance. Although the mechanism of action has not been fully established, it is presumably due to neurolysis and the abolishment of neuromodulated LES relaxation. With the Stretta Catheter (Curon Medical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), radiofrequency energy is generated by a four-channel radiofrequency generator, which delivers 465 kHz/2-5 W per channel/80 V through 4 nickel-titanium needle electrodes. The energy is distributed to the LES submucosal/muscular target area at temperatures less than 100 °C. Multiple prospective non-randomized studies with short-term results, up to 12 mo, showed promising results. Triadafilopoulos et al[24] showed improved quality of life scores, decreased esophageal acid exposure, decreased median DeMeester scores (40.0 to 26.4, P < 0.009) and 70% of patients off PPI at 12 mo for a group of 118 patients. Additional data on long term follow up, including the incidence and natural history of esophagitis in these patients, are required to establish the utility of this procedure.

A second endoscopic therapy for GERD involves the creation of a mechanical barrier at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). Enteryx (Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts) is an ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer that is endoscopically injected within the submucosa or muscular layers of the esophageal wall 1-2 mm caudal to the Z line. This technique has recently been discontinued by the company due to excessive complications[25]. The Gatekeeper Relux Repair System (Medtronic, Tolochenaz, Switzerland) entails the submucosal placement of a poly-acrylonitrile-based hydrogel prosthesis (1.5 mm × 18 mm) above the GEJ. In a prospective, nonrandomized study of 68 patients with a 6 mo follow up, quality of life was improved, median LES pressure (8.8 to 13.8 mmHg, P < 0.01) was increased and 70.4% of the prostheses were still in place at 6 mo[26]. Concerns remain about the durability of the implants, leaving the long term utility of the procedure in question.

The third category of endoluminal procedures employs direct, endoscopic tightening of the LES. This can be achieved by either sewing or plicating the LES. Currently, three endoscopic suturing devices are available: the EndoCinch (BARD Endoscopic Technologies, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA), the ESD (Wilson-Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA), and the Full-Thickness Plicator (NDO Surgical Inc., Mansfield, Massachusetts, USA). The major difference is that the NDO Plicator takes a full thickness suture of gastric fundus whereas the other endoscopic plicators utilize a partial mucosal/submucosal stitch. Partial-thickness sutures have a greater potential to pull through the tissue or migrate over time. The NDO Plicator system appears to have the technical advantages of a single full thickness stitch, with serosa to serosa approximation, leading to direct tightening of the LES, possible lengthening of the LES and favorable altering of the angle of His. Pleskow et al[27] showed in a non-randomized, prospective study of 64 patients with follow-up of 12 mo that mental and physical SF-36 scores were significantly improved. Importantly, 80% of patients had improved distal esophageal acid exposure as evidenced by significantly decreased DeMeester scores (44 to 30, P < 0.001). Moreover, the majority of patients (68%) were off PPI at 12 mo follow-up.

The NDO Plicator as well as the other endoluminal therapies need to be evaluated very carefully in randomized studies. They will probably not replace the existing LARS but possibly serve as a “bridging therapy” finding its place between the Noninvasive GERD therapy and LARS.

ACHALASIA

Heller[28] was the first surgeon to perform an esophagomyotomy for achalasia in Germany in 1913. Over the next several decades, most of the discussion about myotomy centered on the preferred approach to myotomy, whether via an abdominal incision or using a thoracic technique. This discussion became moot in the 1990s as both approaches were supplanted by the laparascopic technique. The first laparoscopic esophagogastromyotomy was performed by Shimi et al[29] in 1991. Current controversies in the treatment of achalasia include the allocation of appropriate therapy, i.e. medical treatment, pneumatic dilation, or surgical treatment, to patients with achalasia. All of these treatments are designed to alleviate the symptoms of achalasia by addressing the failure of the LES to relax upon swallowing. However, in none of these therapies the underlying aperistalsis of the esophagus is addressed.

Pharmacotherapy

Medications are the only true noninvasive option in the treatment of achalasia. However, the medications used to treat achalasia have a short half-life and are variably absorbed due to the poor esophageal emptying experienced by patients with achalasia. As the disease progresses, this treatment modality becomes less and less effective. Calcium channel blockers and nitrates have been widely used, with the sublingual application being preferred[30,31]. Both medications effectively reduce the baseline lower esophageal sphincter tone, but they neither improve LES relaxation nor augment esophageal peristalsis. Persistent dysphagia and adverse effects including headaches, hypotension and peripheral edema make this treatment even more problematic[30,32]. The current recommendations for pharmacotherapy are limited to patients who are early in their disease process, without significant esophageal dilatation, or patients who are high risk for more invasive modalities. Finally, medications should be considered for patients who decline other treatment options.

Botulinum toxin

Direct injection into the lower esophageal sphincter with Botulinum toxin A (Botox, Allergan, Irvine, California) irreversibly inhibits acetylcholine release from cholinergic nerves. This results in decreased constriction of the sphincter and a temporary amelioration of achalasia related symptoms. Following Botox injection, about 60%-85% patients suffering from achalasia will note an improvement in their symptoms[33]. However, in Botox responders, symptoms recur in more than 50% of patients by 6 mo[34,35]. While repeated injections are technically possible, reduced efficacy is seen with each subsequent injection. Repeated esophageal instrumentation with Botox treatment inevitably causes an inflammatory reaction at the gastroesophageal junction. The resulting fibrosis may make subsequent surgical treatment more difficult and/or increase the complication rate. Fortunately, there has been recent evidence that despite Botox therapy, laparoscopic Heller myotomy is as successful as myotomy in Botox-naïve patients. However, prior Botox injection did increase the intraoperative esophageal perforation rate from 2% to 7%[36]. Botulinum toxin therapy is generally recommended for patients who are unwilling to undergo a more invasive treatment.

Pneumatic dilation

Since the original 17th century description by Willis[37], who used a sponge attached to the distal end of a whale bone to dilate a distal esophageal obstruction, the idea of stretching the lower esophagus (today with polyethylene balloons) is still considered the most effective non-surgical treatment for achalasia. Under direct endoscopic visualization, a balloon is placed across the LES and is inflated up to 300 mmHg (10-12 psi)for 1-3 min. The goal is to produce a controlled tear of the LES muscle to render it incompetent, thereby relieving the obstruction. After pneumatic dilation, good to excellent response rates can be achieved in 60% of patients at one year[38]. Long-term results are less satisfactory. At 5 years, only 40% note symptom relief and at 10-year follow-up, a mere 36% of patients have relief of dysphagia[39,40]. Repeat dilatations are technically possible but show a decreased success rate. The most feared complication of pneumatic dilatation is a perforation of the distal esophagus, which frequently occurs at the left posterior lateral aspect (Boerhaave.s triangle). Risk factors for perforation include a widely dilated esophagus (>7 cm), hiatal hernia, or the presence of an epiphrenic diverticulum. The rate of esophageal perforations during pneumatic dilation is approximately 2%[41]. The current recommendations regarding pneumatic dilation prior to (or instead of) surgical therapy depends upon the referring physician’s opinions, the surgeon’s expertise, and the patient’s preference.

Surgical therapy

Heller first described the surgical destruction of the gastroesophageal sphincter, as therapy for achalasia, in 1913. His original technique used 2 parallel myotomies that extended for at least 8 cm on the distal esophagus and proximal stomach. The conversion to a single anterior myotomy was first proposed by De Brune Groenveldt in 1918. During the 1950s, the thoracic approach to esophagomyotomy was perfected, and in parts of the world, became the preferred technique. Despite the excellent results in improving the dysphagia, open Heller myotomy had a prolonged hospital stay and recovery time. Since the inception of minimally invasive techniques, both the open transabdominal repair and the thoracic approach have fallen out of favor.

First performed by Pellegrini et al[42] in 1992, the thoracoscopic approach showed promise, with excellent symptom relief. Unfortunately, technical factors limit the extension of the myotomy well onto the cardia of the stomach and it also makes a concomitant antireflux procedure difficult. Consequently, a higher rate of persistent and recurrent dysphagia (up to 26%) and GERD (35%) occur with this approach. When compared to the laparoscopic technique, this approach results in more postoperative pain and a longer hospital stay.

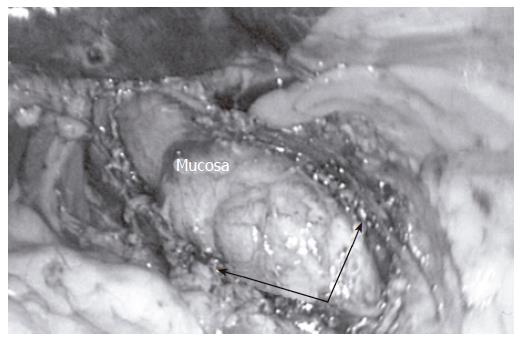

At this time, the laparoscopic approach is considered superior to the above mentioned surgical therapies. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy (Figure 3) is noted to have a very low morbidity and mortality rate, less postoperative pain, improved cosmesis, and a faster recovery compared to more invasive surgical therapies. Most importantly, excellent symptom relief is noted in 90% of patients[43]. This has established the laparoscopic approach as the premier choice for the treatment of achalasia.

Figure 3 The goal of the Heller myotomy is full-thickness division of the muscular layers (arrows) of the distal esophagus.

The myotomy should be long enough to ensure complete obliteration of the lower esophageal sphincter.

The current indications for laparoscopic surgical treatment of achalasia include patients less than 40 years of age, patients with persistent or recurrent dysphagia after unsuccessful Botox injection or pneumatic dilation, and patients who are high risk for perforation from dilation. This latter group includes patients who have previously undergone surgery at the GE junction, those with esophageal diverticula, and those with distorted lower esophageal anatomy. Patients may prefer surgical therapy for a more durable, long-term result, its superior safety profile, and the decreased likelihood of reintervention.

Currently there are two controversies concerning achalasia discussed within the surgical community. The first involves the extent to which the myotomy is extended onto the stomach. Everyone concurs that a surgical myotomy predisposes patients to postoperative GERD; many surgeons also add an antireflux procedure to address this potential problem. Thus the second controversy involves whether to add an antireflux procedure, and if so, which type of antireflux procedure.

The proximal extent of the myotomy is typically carried 5-6 cm proximal to the lower esophageal sphincter. Whether to carry the distal extent of the traditional 1-2 cm beyond the LES or to be more aggressive and carry the myotomy at least 3 cm onto the stomach is now debated. Oelschlager et al[44] found less dysphagia and subsequently fewer interventions to treat the recurrent dysphagia in favor of the at least 3 cm distal myotomy group (3% vs 17%).

The necessity and type of antireflux procedure to prevent GERD after myotomy is the second widely discussed topic. Arguments against performing any antireflux procedure include some surgeo’s reports of an adequate cardiomyotomy without postoperative reflux. Additionally, performing a fundoplication will obviously prolong the operative time, and there is also a proposed concern about adding a fundoplication in the setting of an aperistaltic esophagus. Proponents supporting the addition of an antireflux procedure mostly favor a partial (Dor, Toupet) over a total (Nissen) fundoplication to avoid a functional obstruction (from the fundoplication) and the persistence of dysphagia.

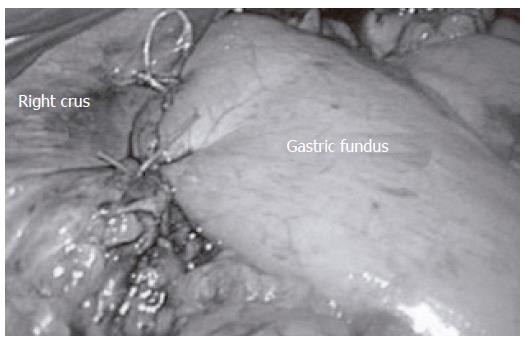

The anterior, 180-degree, Dor fundoplication (Figure 4) and the posterior, 270-degree Toupet fundoplication are the two most commonly performed antireflux procedures in combination with the Heller myotomy. Unfortunately, the lack of prospective randomized studies comparing these two procedures leads to no clear advantages of one partial fundoplication over the other. Proponents of the posterior fundoplication believe that it better prevents re-approximation of the myotomy and believe that it is more effective against GERD. Advocates of the anterior fundoplication procedure argue that it is easy to perform, it protects the anterior esophagus following myotomy and it leaves the posterior anatomy intact. Acknowledging these facts, the authors believe the anterior fundoplication is the best technique to alleviate dysphagia and control reflux symptoms.

Figure 4 The Dor fundoplication is a 180-degree anterior folding of the gastric fundus over the distal esophagus.

In conclusion, LARS and laparoscopic Heller myotomy are the agreed upon gold standard for surgical treatment of GERD and achalasia, respectively. Both are safe and effective treatment for patients with lower morbidity and mortality, shorter hospital stay and recovery period and less postoperative pain when compared to traditional open procedures. Additionally, excellent subjective and objective long-term results with at least 90% patient satisfaction have been observed, making LARS and laparoscopic Heller myotomy the treatment of choice in the experienced hands of dedicated minimally invasive surgeons.