Published online Jan 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i2.336

Revised: June 28, 2005

Accepted: July 10, 2005

Published online: January 14, 2006

Hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) is defined as a clinical triad including liver disease, abnormal pulmonary gas exchange and evidence of intrapulmonary vascular dilatations. We report a 61-year-old male presented with fatigue, long-lasting fever, loss of weight, signs of portal hypertension, hepatosplenomegaly, cholestasis and progressive dyspnoea over the last year. Clinical, laboratory and histological findings confirmed the diagnosis of granulomatous hepatitis. HPS due to hepatic granuloma-induced portal hypertension was proved to be the cause of severe hypoxemia of the patient as confirmed by contrast-enhanced echocardiography. Reversion of HPS after corticosteroid therapy was confirmed by a new contrast-enhanced echocardiography along with the normalization of cholestatic enzymes and improvement of the patient’s conditions. This is the first case of complete reversion of HPS in a non-cirrhotic patient with hepatic granuloma, indicating that intrapulmonary shunt in liver diseases is a functional phenomenon and HPS can be developed even in miscellaneous liver involvement as in this case.

- Citation: Tzovaras N, Stefos A, Georgiadou SP, Gatselis N, Papadamou G, Rigopoulou E, Ioannou M, Skoularigis I, Dalekos GN. Reversion of severe hepatopulmonary syndrome in a non cirrhotic patient after corticosteroid treatment for granulomatous hepatitis: A case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(2): 336-339

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i2/336.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i2.336

Hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) is defined as the triad of advanced liver disease, hypoxemia (PaO2 < 70 mmHg or increased alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient > 20 mmHg) while breathing room air, and evidence of intrapulmonary vascular dilatations (IPVDs) resulting in an excess perfusion for a given state of ventilation irrespective of the presence or absence of cardiopulmonary disease [1,2]. HPS is a quite common condition in patients with advanced liver diseases as it has been reported in approximately 10-20% of candidates for liver transplantation [3]. The incidence rate of IPVDs in patients with end-stage liver disease is 13-47% [4] and 10% in normoxemic patients with early liver cirrhosis [5]. However, the prevalence of HPS according to the above mentioned criteria ranges from 5% to 30% [2,6,7]. Though the majority of patients with HPS have developed cirrhosis and portal hypertension, the presence of HPS is occasionally reported in cases of portal hypertension without the existence of cirrhosis. Actually, HPS has been reported in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome [8] and acute [9] or chronic viral hepatitis [4].

In this paper, we describe a non-cirrhotic patient with granulomatous hepatitis presented with signs of HPS, which responded completely to corticosteroid administration.

A 61-year-old man was admitted to our department because of low-grade fever (up to 38 ºC), weakness, fatigability, loss of weight (10 kg during the last 8 mo) and progressive dyspnoea over the last year. The patient reported pruritus in the last 20 d and low exercise tolerance. He was an ex-smoker (80 packs a year) until 8 months earlier and had a 40-year history of alcohol abuse (over 100g of alcohol daily).

On admission, he was pale and well orientated, his temperature was 37.4ºC, his pulse rate was 60 per minute and his blood pressure was 110/60 mmHg. Physical examination revealed profound dyspnoea with a high respiratory rate (30 per minute), platypnea and cyanosis, jaundice, hepatoslenomegaly without the presence of ascites, palmar erythema, digital clubbing and extended cutaneous spider naevi on the upper half of the body. Pulmonary auscultation and heart sounds were normal without murmurs or gallops. Further physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory test on admission showed mild normochromic-normocytic anaemia with 35% haematocrit, 118 g/L haemoglobin, 3.48 × 1010/L reticulocytes and normal platelet count (16.8×109/L). White blood cells were 3.5×109/L with 57.4% segmented granulocytes, 29.5% lymphocytes and 9.9% monocytes. Peripheral blood smear was normal. Abnormal biochemical parameters were 67 mg/dL urea, 1.47 mg/dL creatinine, 11.0 mg/dL serum calcium, 3.2 mg/dL total bilirubin, 1.26 mg/dL direct bilirubin, 348 U/L alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (upper normal <104 U/L), 516 U/L γ-glutamyltranspeptidase (γ-GT) (upper normal <40 U/L), 73U/L aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (upper normal <40U/L) and 43U/L alaninoaminotransferase (ALT) (upper normal <40 U/L). Urinalysis revealed specific gravity of 1.010, pH 6.0, 1-2 red blood cells/HPF, 0-1 white blood cell/HPF, without casts, 760 mg/24h proteinouria and elevated urine calcium excretion (326 mg/24h) accompanied with reduced creatinine clearance (38.7mg/dL). Electrocardiography and chest X-ray radiography were normal. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed first-degree oesophageal varices and mild portal gastropathy.

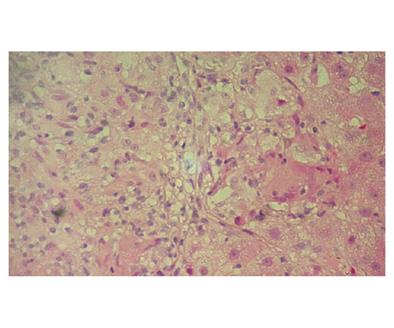

Sequential bacterial cultures of blood, urine and marrow were negative for tuberculosis bacilli, brucellosis or other bacterial and fungal infectious diseases. Serology for hepatitis A, B, C and human immunodeficiency virus infections was negative. Abdominal ultrasound did not reveal lymphadenopathy, ascites or hepatic nodules. Abdominal dynamic spiral computed tomography (CT) confirmed the presence of hepatosplenomegaly. Serum immunoglobulin M was mildly elevated (269mg/dL; upper normal limit: 249mg/dL) but antimitochondrial antibodies by ELISA, Western blot and indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) using commercial and in-house substrates were negative. Antinuclear autoantibodies using IIF were also negative. Liver biopsy revealed multiple non-caseating epithelioid granulomas and mild perisinusoidal fibrosis without any histological sign of cirrhosis (Figure 1). Multiple non-caseating granulomas were also found in the bone marrow biopsy specimen. High resolution CT of the chest was normal. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid revealed the presence of lymphocytes mainly T-cells in 94% with a CD4/CD8 ratio of 2. Transbronchial biopsy was negative for granulomas. The above clinical, laboratory, histological and radiological findings indicated that idiopathic granulomatous hepatitis was the most likely diagnosis though the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis without apparent involvement of the lungs could not be rule out.

Arterial blood gas analysis (while breathing room air) showed hypoxemia with arterial oxygen tension (PaO2): 53 mmHg; PaCO2: 27.9 mmHg; pH: 7.48; bicarbonate: 21mM; PA-aO2: 66.7 mmHg. Supplemental 100% oxygen was administered and PaO2 was elevated to 153 mmHg. Arterial blood gases while breathing room air became worse at the upright position (Pa,O2: 49 mmHg, Pa,CO2: 23.9 mmHg, pH: 7.42, bicarbonate: 15.5mmol/L) while improved at supine position. The observed orthodeoxia was compatible to the clinical improvement noted during supine position (platypnea). Spirometry revealed findings of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease of stage I, according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseases (GOLD) classification[10]: FVC: 4.14 lt (110 % pred), FEV1: 2.68 lt (90 % pred), FEV1/FVC: 65%, FEF25-75%: 1.43 L/sec (42 % pred). The diffusion capacity test showed a moderately reduced DL, CO/VA: 0.75 (56% pred).

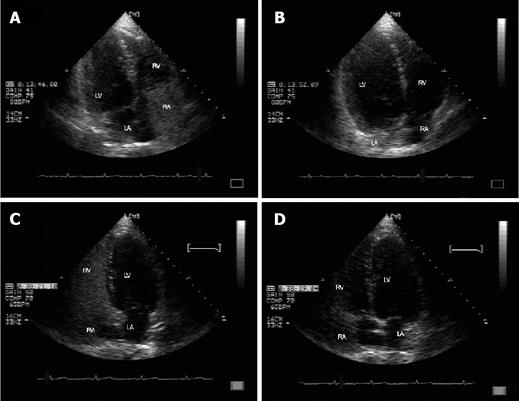

Contrast-enhanced echocardiography with agitated saline showed microbubble opacification in the left atrial after six heart beats later of the right heart chamber opacification in the absence of intracardiac septal defects, confirming the presence of intrapulmonary shunt (Figures 2A and 2B). Technetium 99m-labelad macroaggregated albumin scanning was also positive for IPVDs (increased uptake of radionuclide over the kidneys and brain), confirming the diagnosis of HPS on the basis of portal hypertension due to hepatic granulomas.

The patient started to receive methylprednisolone (32 mg daily) and continuous home oxygen therapy (2L/min) for at least 18 hours per day. Three months later, his performance status was excellent and arterial blood gas analysis (while breathing room air) was almost normal (PaO2: 85 mmHg, PaCO2: 36.2 mmHg, pH: 7.43, bicarbonate: 25.4mmmol/L with PA-aO2 19.7 mmHg). Thirteen months after his first evaluation, he was still on methylprednisolone (4 mg daily). His performance status was very good with his blood gas, liver function and calcium concentration within normal limits. In addition, after treatment the spleen was not palpable, a new upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was normal and a new contrast-enhanced echocardiography revealed no intrapulmonary shunt (Figures 2C and 2D).

This case report describes a patient with HPS due to portal hypertension as a result of granulomatous hepatitis. Though the most common causes of granulomatous hepatitis are infections and systemic sarcoidosis, we were not able to confirm such a diagnosis (due to the absence of lung involvement). Indeed, liver involvement in sarcoidosis is not unusual as 50-80% of patients are affected but almost all of them have also lung disease [11]. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of complete reversion of HPS after corticosteroid treatment in a non-cirrhotic patient suffering from portal hypertension due to idiopathic granulomatous hepatitis.

HPS is a well-known complication in patients with advanced liver disease. Its major signs and symptoms include the presence of dyspnoea (particularly in exertion), cyanosis, digital clubbing, platypnea and orthodeoxia (a decrease in PaO2 of more than 3 mmHg when the patient moves from the supine to the standing position)[12-14]. The pathogenesis of HPS is well delineated [1]. The syndrome occurs as a result of precapillary and capillary pulmonary vascular dilatations, causing apparent right-to-left intrapulmonary shunting, though there is no true anatomic shunt [15,16]. However, the capillaries may become dilated to 500 μm in diameter (normal range 8-15 μm) [16,17]. Hypoxemia arises due to a combination of ventilation and perfusion mismatching, oxygen diffusing limitation and intrapulmonary shunting [13,16,18]. These intrapulmonary vascular abnormalities in advanced liver cirrhosis are attributed to an excess production of vasodilators that affect the lung vascular system via porto-systemic shunt, with nitric oxide as the most likely mediator [19]. The above hypothesis is in accordance with the complete reversion of the syndrome when liver transplantation is successful in patients with end-stage liver disease and HPS [12,15,16,19].

However, it was reported that HPS occurs occasionally in non-cirrhotic cases of portal hypertension[4,8,9] and could completely reverse after the causative agent is eradicated[8,9]. Under this context, we believe that in our case the corticosteroid treatment of granulomatous hepatitis led to the reversion of HPS via an improvement of portal hypertension as the presence of liver granuloma per secan result in the development of sinusoidal portal hypertension irrespective of the presence or absence of cirrhosis.

Staging of the severity of HPS is important because severity influences survival and is useful in determining the timing and risks for liver transplantation. A classification of the severity of HPS based on oxygenation abnormalities in four stages has been proposed [1,6]. According to this classification our patient had severe HPS as he presented with 49 mmHg PaO2 while breathing room air, 153 mmHg PaO2 when supplemental oxygen was admitted and a significant elevation of PA-aO2. Contrast-enhanced echocardiography is the standard method for the diagnosis of HPS [12]. Technetium 99m-labeled macroaggregated albumin scanning is another method of detecting IPVDs [20] and can be used to quantify the magnitude of shunting.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge this is the first case study to describe complete reversion of HPS due to granulomatous hepatitis. We consider that the clinical and laboratory improvement of severe HPS in this case is due to the treatment response, leading to an improvement of portal hypertension as attested by the complete normalization of cholestatic enzymes, the absence of oesophageal varices and the shrinkage of spleen after corticosteroid administration. The absence of cirrhosis proved by liver biopsy may be a determinant factor for the reversion of HPS. It seems that HPS can be reversed (alleviation of dyspnea, improvement of hypoxemia) when liver function and portal hypertension are improved. This further supports the fact that the development of intrapulmonary shunt in liver diseases is mainly a functional phenomenon and HPS can be observed even in miscellaneous liver involvement as in this case.

| 1. | Hervé P, Lebrec D, Brenot F, Simonneau G, Humbert M, Sitbon O, Duroux P. Pulmonary vascular disorders in portal hypertension. Eur Respir J. 1998;11:1153-1166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Naeije R. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:163-169. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Krowka MJ, Mandell MS, Ramsay MA, Kawut SM, Fallon MB, Manzarbeitia C, Pardo M, Marotta P, Uemoto S, Stoffel MP. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: a report of the multicenter liver transplant database. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:174-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Teuber G, Teupe C, Dietrich CF, Caspary WF, Buhl R, Zeuzem S. Pulmonary dysfunction in non-cirrhotic patients with chronic viral hepatitis. Eur J Intern Med. 2002;13:311-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mimidis KP, Karatza C, Spiropoulos KV, Toulgaridis T, Charokopos NA, Thomopoulos KC, Margaritis VG, Nikolopoulou VN. Prevalence of intrapulmonary vascular dilatations in normoxaemic patients with early liver cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:988-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schenk P, Fuhrmann V, Madl C, Funk G, Lehr S, Kandel O, Müller C. Hepatopulmonary syndrome: prevalence and predictive value of various cut offs for arterial oxygenation and their clinical consequences. Gut. 2002;51:853-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gupta D, Vijaya DR, Gupta R, Dhiman RK, Bhargava M, Verma J, Chawla YK. Prevalence of hepatopulmonary syndrome in cirrhosis and extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3395-3399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | De BK, Sen S, Biswas PK, Mandal SK, Das D, Das U, Guru S, Bandyopadhyay K. Occurrence of hepatopulmonary syndrome in Budd-Chiari syndrome and the role of venous decompression. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:897-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Regev A, Yeshurun M, Rodriguez M, Sagie A, Neff GW, Molina EG, Schiff ER. Transient hepatopulmonary syndrome in a patient with acute hepatitis A. J Viral Hepat. 2001;8:83-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hurd S, Pauwels R. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseases (GOLD). Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2002;15:353-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Costabel U. Sarcoidosis: clinical update. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2001;32:56s-68s. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hoeper MM, Krowka MJ, Strassburg CP. Portopulmonary hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome. Lancet. 2004;363:1461-1468. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rodriguez-Roisin R, Roca J, Agusti AG, Mastai R, Wagner PD, Bosch J. Gas exchange and pulmonary vascular reactivity in patients with liver cirrhosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:1085-1092. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Krowka MJ, Dickson ER, Cortese DA. Hepatopulmonary syndrome. Clinical observations and lack of therapeutic response to somatostatin analogue. Chest. 1993;104:515-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fallon MB. Hepatopulmonary syndrome: a good relationship gone bad. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1261-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lange PA, Stoller JK. The hepatopulmonary syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:521-529. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Schraufnagel DE, Kay JM. Structural and pathologic changes in the lung vasculature in chronic liver disease. Clin Chest Med. 1996;17:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gómez FP, Martínez-Pallí G, Barberà JA, Roca J, Navasa M, Rodríguez-Roisin R. Gas exchange mechanism of orthodeoxia in hepatopulmonary syndrome. Hepatology. 2004;40:660-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dinh-Xuan AT, Naeije R. The hepatopulmonary syndrome: NO way out. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Krowka MJ, Wiseman GA, Burnett OL, Spivey JR, Therneau T, Porayko MK, Wiesner RH. Hepatopulmonary syndrome: a prospective study of relationships between severity of liver disease, PaO(2) response to 100% oxygen, and brain uptake after (99m)Tc MAA lung scanning. Chest. 2000;118:615-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Wang XL and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Li HY