Published online May 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i19.2991

Revised: January 8, 2006

Accepted: January 14, 2006

Published online: May 21, 2006

Since the discovery of Campylobacter-like organisms Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) more than two decades ago the possibility of a relationship with gastric cancer has been postulated, tested and supposedly proven. There have been numerous human studies of various designs from many countries around the world. Several meta-analyses have been published and more recently a small number of experimental animal studies were reported looking at the association between H pylori infection and gastric cancer. Over the years, the human epidemiological studies have produced conflicting results; the meta-analyses have as one would expect produced similar pooled estimates; while the early experimental animal studies require replication. The exact mechanisms by which H pylori might cause gastric cancer are still under investigation and remain to be elucidated.

- Citation: Eslick GD. Helicobacter pylori infection causes gastric cancer A? review of the epidemiological, meta-analytic, and experimental evidence. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(19): 2991-2999

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i19/2991.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i19.2991

The suggestion of a link between Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection and gastric cancer was first proposed by co-discoverer Marshall in 1983[1]. It is of interest that at that time the majority of physicians and scientists around the world did not even believe that there was a link between H pylori and gastritis[2,3]. Just over a decade later in 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified H pylori as a definite class 1 carcinogen[4], despite some conflicting results[5,6]. No experimental studies had been conducted at that time and the epidemiological studies that had been done produced mixed results. Almost all of the studies did not take into consideration other important potential confounders or sources of interaction (e.g., salt intake, diet, alcohol consumption, and smoking). A number of additional studies have also failed to detect an association even in high risk populations[7,8], which has led some to question whether there is a causal link[9]. However, these epidemiological observations appear to be directly supported by early data from animal models on cancer development following H pylori infection[10].

This review addresses some of the controversies in the expanding literature supporting a positive association for H pylori infection leading to gastric cancer. This review will not address the relationship between H pylori and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. An excellent review on this topic has recently been published[11]. Specifically, this review aims to assess the epidemiological evidence based on Bradford Hill’s criteria of causality[12], experimental data using Henle-Koch’s[13] postulates (Evan’s postulates will not be reviewed)[14] and summarize the meta-analytic evidence for the association between H pylori and gastric cancer.

The search strategy involved the major computer databases, including Medline, PubMed, EMBASE and Current Contents (January 1983 to February 2006). The search methodology involved using combinations of the following keywords: H pylori, Camplyobacter pylori, Campylobacter pylordis, gastric cancer, gastric carcinoma, stomach cancer, meta-analysis, systematic review, gastric adenocarcinoma, experimental, animal studies, systematic review. Additional manual searches were made using the reference lists from the selected articles to retrieve other papers relevant to the topic. No language restriction was placed on any of the literature searches.

In 1994, The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) published a report based on a meeting of experts between 7-14 June of that year in Lyon, France[4]. In terms of a link between H pylori and gastric cancer, the conclusions reached in this report stated that there was sufficient evidence for carcinogenicity among humans and inadequate evidence for carcinogenicity in animals, with an overall evaluation classifying H pylori as a group 1 definite carcinogen. Sufficient evidence relating carcinogenicity in humans as stated in the report is: “Sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity: The Working Group considers that a causal relationship has been established between exposure to the agent, mixture or exposure circumstance and human cancer. That is, a positive relationship has been observed between the exposure and cancer in studies in which chance, bias and confounding could be ruled out with reasonable confidence.” Inadequate evidence relating carcinogenicity in animals as stated in the report is: “Inadequate evidence of carcinogenicity: The studies cannot be interpreted as showing either the presence or absence of a carcinogenic effect because of major qualitative or quantitative limitations, or no data on cancer in experimental animals are available.”

In the overall evaluation a Group 1 carcinogen as stated in the report is: “Group 1 - The agent (mixture) is carcinogenic to humans: The exposure circumstance entails exposures that are carcinogenic to humans: This category is used when there is sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in humans. Exceptionally, an agent (mixture) may be placed in this category when evidence in humans is less than sufficient but there is sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals and strong evidence in exposed humans that the agent (mixture) acts through a relevant mechanism of carcinogenicity.” The findings of the IRAC were four years before the published experimental animal data or meta-analysis of the human epidemiological studies[10,15]. So why was H pylori given such a classification Would another classification have been more appropriate and if so, which one

The overall IARC evaluation options (Group 1, Group 2A, Group 2B, Group 3, Group 4) appear to assume that there are usually experimental animal data but may not be sufficient human data to support that an agent is carcinogenic to humans. However, in the case of H pylori and gastric cancer the opposite is actually true. There were human studies, but at that point in time (1994) there were no actual animal or experimental data. From a cause and effect point of view, one would think that animal data would be essential to link an agent with causing carcinogenic effects, but this does not occur with H pylori. Of all the agents assessed in the IARC monograph, only H pylori with inadequate animal evidence but ‘sufficient human evidence’ was classified as a class 1 definite carcinogen (Table 1). All the other agents except for H pylori and Opisthorchis felineus had at least a limited amount of animal data on which an overall evaluation regarding their carcinogenicity to humans was based. Therefore, based on the data available in 1994 regarding H pylori and gastric cancer, it might appear that the IARC prematurely classified H pylori as a definite class 1 carcinogen. This is because the available epidemiological evidence was insufficient in quality (confounders not adequately assessed) and quantity to establish causal link and there were no experimental animal studies at that time.

| Agent (infectionwith) | Degree of evidence of carcinogenicity | Overall evaluation | |

| Human | Animal | ||

| Schistosoma haematobium | Sufficient | Limited | Definite carcinogen |

| Schistosoma japonicum | Limited | Limited | Possible carcinogen |

| Schistosoma mansoni | Inadequate | Limited | Not classifiable |

| Opisthorchis viverrini | Sufficient | Limited | Definite carcinogen |

| Opisthorchis felineus | Inadequate | Inadequate 1 | Not classifiable |

| Clonorchis sinensis | Limited | Limited | Probable carcinogen 2 |

| Helicobacter pylori | Sufficient | Inadequate 1 | Definite carcinogen |

In 1965, Bradford Hill (1897-1991) published his seminal paper titled “The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation”[12] This paper was initially written to assess causal links between sickness and injury related to work. Bradford Hill’s criteria will be used to assess the possibility of a causal association between H pylori and gastric cancer[16].

Consistency: The association is consistent when results are replicated in studies in different settings using different methods. The human epidemiological studies have produced mixed results with approximately 50% finding a positive association between H pylori infection and gastric cancer and 50% reporting a negative relationship[15,17,18]. This variation also exists within countries and between countries[15,17,18]. The majority of studies reported were case-control in design with a smaller number of cohort (usually nested case-control) studies which also provided mixed results[15,17,18].

Strength: This is defined by the size of the risk as measured by appropriate statistical tests. The strength of the relationship between H pylori and gastric cancer varies quite considerably. Negative studies have produced results as low as (OR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.24-1.19)[6], and positive studies as high as (OR: 13.3, 95% CI: 5.30-35.60)[19]. The average strength of the relationship as determined by meta-analysis produces an effect size (odds ratio) of approximately 2.00[15,17,18].

Specificity: This is established when a single putative cause produces a specific effect. H pylori is predominantly found in the stomach and is associated with gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric cancer; however, it is linked with numerous extra-gastric conditions including foetal intra-uterine growth restrictions[20], glaucoma[21], Raynaud’s

phenomenon[22], gallstones[23], primary headache[24], diabetes[25], ischemic heart disease[26], Sjögren’s syndrome[27], Schönlein-Henoch purpura[28], autoimmune thyroiditis[29], chronic bronchitis[30], Parkinson’s disease[31], non-arterial anterior optic ischemic neuropathy[32], chronic idiopathic urticaria[33], rosacea[34], alopecia areata[35], sideropenic anemia[36], growth retardation[37,38], late menarche[39], hepatic encephalopathy[40], and stroke[41]. Thus, currently H pylori is not associated with a single specific condition or disease within or outside the human stomach[42-46]. It must be remembered that none of these conditions are causally linked with H pylori.

Dose-response relationship: An increasing level of exposure (in amount and/or time) increases the risk. It is well known that infection with H pylori involves an inflammatory process occurring over many years[47-51], thus, the risk of gastric cancer may correlate with the duration of infection with H pylori. Therefore, those individuals who are infected during childhood have a longer time to develop mutations compared to those who acquire infection during adulthood. It has been suggested that a child’s stomach might be physiologically different from an adult’s stomach, because children have less acute inflammation and an increased number of lymphoid follicles than adults[52]. However, the amount of organisms living in a human’s stomach has never been correlated with pathology.

Temporal relationship: Exposure always precedes the outcome. This is the only absolutely essential criterion. Current epidemiological evidence suggests that infection is usually acquired during childhood and is attributed to a cohort effect[53-57]. A recent study showed that age of acquisition after one year of age is not the most important factor related to the differences in incident rates of gastric cancer in adulthood[58]. However, studies have also shown that re-infection with H pylori is also possible, even though it may occur infrequently[59,60].

Biological plausibility: The association agrees with currently accepted understanding of pathobiological processes. This criterion should be applied with caution. The prospect that cancer might be spread via an infectious mechanism has been considered for centuries[61,62]. Moreover, over the last decade there has been an exponential increase in the scientific knowledge related to infectious agents associated with cancer[63-65]. There are a large number of infectious agents associated with cancers including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human papillomaviruses (HPVs), hepatitis B or C virus, human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8), Salmonella typhi/paratyphi, Schistosoma hematobium, polyoma viruses[66-72]. Over the last decade there has certainly been an enormous increase in the amount of data on association between H pylori and gastric cancer, with numerous studies and hypothetical mechanisms explored[73-77]. However, while it is definitely plausible that H pylori could cause gastric cancer, at present the exact mechanism remains unknown.

Coherence: The association should be compatible with existing theory and knowledge. Epidemiologically, at times, there are clear signs of a relationship between H pylori and gastric cancer, for example, studies that reported a high prevalence of H pylori among a population with a high rate of gastric cancer (e.g., Japan)[9,78,79]. Conversely, there are times when a high prevalence of H pylori correlated with the low rate of gastric cancer (e.g., Africa)[9,79,80]. However, one African study reported that there was no difference in prevalence of H pylori infection among gastric cancer cases and non-ulcer dyspepsia controls[81]. The fact that only approximately 1% of those infected with H pylori actually go on to develop gastric cancer suggests a lack of coherence. Of course there are exceptions; in Changle, China, up to 20% of H pylori infected individuals developed gastric cancer. Should not all those infected with H pylori eventually develop gastric cancer Indeed, if 50% of the world is infected then this equates to 30 million cases of gastric cancer, which is a gigantic number of potentially preventable malignancies. The latest epidemiological data from GLOBOCAN 2002 (data reported 2-5 years earlier) reported that there were 933 937 incident cases and 700 349 deaths due to gastric cancer in that year (Table 2)[79]. Histopathologically, there is a paradox where H pylori organisms are not found in the stomachs of gastric cancer cases, which may explain the lower antibody response among these patients[82-84]. These are arguments against coherence for the causal relationship between H pylori and gastric cancer.

| Incidence | Mortality | Prevalence | ||||||

| n | CR | ASR | Deaths | CR | ASR | 1-year | 5-year | |

| Males | ||||||||

| World | 603 419 | 19.3 | 22 | 446 052 | 14.3 | 16.3 | 302 067 | 951 403 |

| Developed | 195 782 | 33.7 | 22.3 | 128 721 | 22.2 | 14.5 | 117 377 | 409 777 |

| Under-developed | 405 211 | 15.9 | 21.5 | 315 603 | 12.4 | 17 | 184 690 | 541 626 |

| Females | ||||||||

| World | 330 518 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 254 297 | 8.3 | 7.9 | 166 436 | 522 156 |

| Developed | 115 372 | 18.8 | 10 | 83 515 | 13.6 | 6.9 | 66 319 | 227 316 |

| Under-developed | 214 024 | 8.7 | 10.4 | 169 971 | 6.9 | 8.3 | 100 117 | 294 840 |

Experiment: The condition can be altered by an appropriate experimental regimen. This is possibly the most important support for a causal relationship. Thus, the strongest proof for a link between H pylori and gastric cancer would be established only if controlled trials demonstrate that elimination or prevention of H pylori infection prevents malignancy. An animal study has documented that among Mongolian gerbils treated with N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU) and infected with H pylori where 2 of the 6 groups underwent eradication of H pylori infection at 21 weeks, after 50 weeks they showed a decrease in the number of gastric cancers developed[85].

Recently, a human prospective randomized, placebo-controlled prevention trial compared patients who received eradication therapy for H pylori (n = 817) and those taking placebo (n = 813) and at follow-up (7.5 years) determined the incidence of gastric cancer between the groups[86]. However, there was no significant difference in gastric cancer incidence between those who received eradication therapy and placebo (P = 0.33). This study was criticised for being stopped early, as it was believed that if the study had continued for a few more years it might have yielded more conclusive results[87]. Kamada et al[88] conducted a prospective non-randomized follow-up study of 1787 patients who underwent H pylori eradication therapy and were followed up after 9 years. Gastric cancer occurred in 20 patients (1.1%), while early gastric cancer consisted of 5.7% (6/105) after endoscopic resection. This study concluded that even after successful eradication therapy for H pylori endoscopic assessment should be undertaken for occult early gastric cancer or severe mucosal atrophy. Moreover, studies trying to determine if gastric atrophy is a reversible process have produced conflicting results[89]. Thus, endoscopic screening in high risk populations still remains appropriate[90,91]. It should be remembered that epidemiological evidence by itself is insufficient to establish causality, but it does provide strong circumstantial evidence.

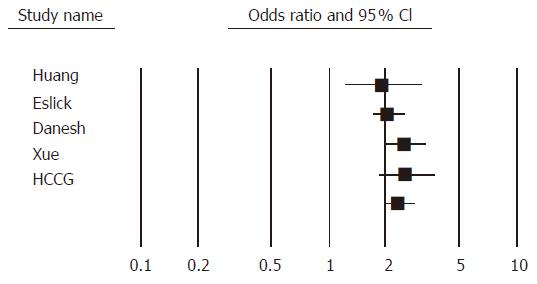

At present, five meta-analyses have been published assessing the relationship between H pylori and gastric cancer[15,17,18,92,93], and one that focuses specifically on the CagA cytotoxin, will be discussed separately[94]. An additional earlier combined-analysis[95] which contained only three early (all published in 1991) prospective studies produced a pooled odds ratio of 3.80 (95% CI: 2.30-6.20). This paper will not be discussed in this review due to the lack of information regarding this particular combined-analysis. These meta-analyses vary in several different ways: (1) the number of studies included in the analysis; (2) the types of studies included; (3) whether the studies were peer-reviewed or in abstract form; (4) published language of the studies; (5) databases used; (6) the search terms used; (7) method of H pylori diagnosis; (8) statistical analyses used; (9) statistical heterogeneity; (10) if quality assessment was undertaken; (11) determination of publication bias; (12) how to deal with duplicate studies; and (13) the number of reviewers involved in data extraction. Of the five meta-analyses that assessed the association between H pylori and gastric cancer the number of studies included in each of the meta-analyses varies mostly due to study design. The number of studies included ranged between 11-44. Moreover, the number of studies used in the statistical analysis is exactly the same as the number of studies included except for one meta-analysis where the analysis was undertaken based on 10 out of the 44 studies (Table 3)[18]. Three of the meta-analyses combined both case-control and cohort studies[15,17,18], whereas, two meta-analyses contained only case-control studies[15,17].

| StudyFactors | Huang et al 1998[16] | Danesh 1999[19] | Eslick et al 1999[18] | Xue et al 2001[93] | HCCG 2001[94] | Huang et al 2003[95] |

| Journal | Gastroenterology | Aliment Pharm Ther | Am J Gastroenterol | World J Gastroenterol | Gut | Gastroenterology |

| Number of studies | 19 | 44 | 42 | 11 | 12 | 16 |

| Cohort studies | 5 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Case-control studies | 14 | 34 | 34 | 11 | 12 | 16 |

| Peer-reviewed papers | 18 | 37 | 42 | † | 12 | 12 |

| Abstracts | 1 | 7 | 0 | † | 0 | 4 |

| Non-English language studies | English only | No restrictions | No restrictions | Chinese only | † | No restrictions |

| Searching method(s) | MEDLINE, | MEDLINE, Reference lists, hand searching | MEDLINE, Current contents, CINAHL, CANCER CD, Biological abstracts, manual searches, contact investigators | Chinese Biomedical database (CBM) | MEDLINE, contact investigators | MEDLINE, PubMed, contact investigators |

| Conference proceedings (1994-1996), manual searches | ||||||

| Search terms used | Campylobacter pylori, stomach neoplasms, Helicobacter pylori | Campylobacter pylori, gastric adenocarcinoma, gastric cancer, | Campylobacter pyloridis, Campylobacter pylori, gastric carcinoma, gastric cancer, Helicobacter pylori | Helicobacter pylori, gastric carcinoma, gastric cancer, precancerous lesion of stomach | † | Helicobacter pylori, meta-analysis, stomach neoplasms |

| Stomach cancer, | ||||||

| Helicobacter pylori | ||||||

| Time period | 1983-1996 | 1983-1998 | 1983-March 1999 | 1995-2001 | 1985-1999 | 1990-2003 |

| H pylori status | Serology only | Serology only | Serology & histology | † | Serology | Serology |

| Statistical analysis | Random-effects M-H or D&L | Inverse-variance- weighted log risk odds | Random-effects D&L | Fixed-effects | Logistic regression | Random-effects D&L |

| Number of studies in analysis | 19 | 10 | 42 | 11 | 12 | 16 |

| Pooled oddas ratio (OR) | 1.92 | 2.5 | 2.04 | 2.56 | 2.36 | 2.28 |

| 95% confidence interval (CI) | 1.32-2.78 | 1.90-3.40 | 1.69-2.45 | 1.85-3.55 | 1.98-2.81 | 1.71-3.05 |

| Overall (P-value) heterogeneity | 0.2 | > 0.05 | 0.001 | > 0.05 | 0.09 | < 0.001 |

| Quality assessment | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Assessment of publication bias | No | No | Yes | No | † | Yes |

| Duplicate studies | Removed | † | Removed | † | † | Removed |

| Number of reviewers | Two | One | Two | † | † | Three |

Two meta-analyses placed no language restrictions on the publications included[17,18], one incorporated only English language publications[15] while another only used those published in Chinese[92]. The types and number of databases used differed with the majority using only one database[15,18,92,93], and one meta-analysis using five databases[17]. Only three meta-analyses incorporated manual searches of reference lists[15,17,18], one searched conference proceedings[15], and two contacted investigators[17,93]. The meta-analyses also used assorted search terms varying in number between 3-5. Three meta-analyses only used studies that determined H pylori status by serology[15,18,93] while one used a combination of serology and histology[17] and one did not state the method of H pylori determination[92]. Statistical methods also differed with four of the meta-analyses using a combination of a fixed and random-effects procedure. The pooled estimates from these five meta-analyses ranged between 1.92-2.56 (mean 2.28) with confidence intervals ranging between 1.35-3.55. Quality assessment was only undertaken in two of the meta-analyses[15,17], with only one using quality scores[17]. In addition, publication bias was only determined in one of the meta-analyses[17]. Duplicate studies were removed in two of the meta-analyses[15,17], and not stated in the other meta-analyses. The number of assessors also differed between the meta-analyses ranging between one and three and two studies having an unknown number of assessors.

The additional meta-analysis, focused on the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer[94]. Previous studies have reported a higher prevalence of cagA-positive strains among populations with a high incidence of gastric cancer[94]. This meta-analysis included 16 case-control studies, and there were no language restrictions used on the literature search which included the databases of Medline and PubMed that only assessed publications between the years 1990-2003. The study produced a pooled odds ratio of 2.28 with a confidence interval ranging between 1.71-3.05. However, there was significant heterogeneity among the studies included in this analysis. A quality assessment was undertaken but did not involve producing a score for each particular study included in the meta-analysis. The authors did assess publication bias, while duplicate studies were removed and three authors conducted the literature searches. One meta-analysis[17] found that younger subjects were at lower risk (OR 0.77, 95% CI: 0.68-0.89) of developing gastric carcinoma if infected with H pylori, which is supported by the epidemiological data. However, another meta-analysis[15] showed that the odds ratios decreased significantly with increasing age (9.29, 3.43-34.04 aged 20-29 years; 1.05, 0.73-1.52 aged ≥ 70 years). The reason for this difference may be due to the staging of gastric cancer and the difficulty in diagnosing H pylori infection in the advanced stages where the normal gastric mucosa has been destroyed.

All these meta-analyses showed that H pylori infection is associated with approximately a two-fold increased risk of developing gastric cancer (Figure 1). The strength and consistency of these meta-analyses in terms of a lack of heterogeneity (as only one meta-analysis reported heterogeneity) suggests that these observations are reliable. One of the possible reasons for this heterogeneity might be the variation in study design as both case-control and cohort studies were included.

In order to assess a causal relationship experimentally between H pylori and the formation of gastric cancer a systematic approach similar to that applied in epidemiological studies is essential. Historically, Henle-Koch postulates (1877 and 1882)[13] have been used to determine causal relationships, however, these postulates were revised in 1976 by Evans (Evans 1976)[14]. This review will only use Henle-Koch postulates to assess this relationship. These were developed in 1877 by Jacob Henle and subsequently revised in 1882 by Robert Koch. The postulates from Last[16] are: The agent must be shown to be present in every case of the disease by isolation in pure culture. As mentioned previously, not all animals or humans infected with H pylori go on to develop gastric cancer[10]. At present 50% of the animal studies have used carcinogens in combination with H pylori infection[96-98] and the remainder have only used the organism in an attempt to induce gastric cancer[10,99,100].

The agent must not be found in cases of other disease. H pylori is associated with other gastrointestinal diseases (chronic gastritis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, and gastric MALToma) and also a large number of extra-gastric diseases[20-46]. Thus, currently H pylori is not associated with a single specific condition or disease within or outside the human stomach. However, it must be highlighted that none of these disease conditions have as yet been definitively/causally linked with H pylori infection.

Once isolated, the agent must be capable of reproducing the disease in experimental animals. Marshall’s classic back-to-back publications which were published in 1985 in the Medical Journal of Australia where the authors aimed to fulfill Koch’s postulates[101,102]. These publications described the now famous experiment where Dr Marshall ingested a 10 mL suspension of approximately 109 colony forming units of H pylori which had been isolated from a patient with gastritis (then referred to as pyloric Campylobacter). Over the course of the next ten days, the subject developed symptoms (increased abdominal peristalsis, epigastric fullness, vomiting, headache, soft faeces, and halitosis). A gastroscopy was performed and biopsies taken for both light and electron microscopy, which revealed gastritis and spiral organisms (pyloric Campylobacter). These organisms were cultured and freeze-dried. The authors were able to fulfil Koch’s postulates in humans for gastritis[101,102]. However, it is not possible to complete Koch’s postulates for gastric cancer in humans. It was not until 1998 when the first report by Watanabe et al[10] of H pylori leading to gastric carcinogenesis that animal models could be assessed in terms of Koch’s postulates. It has been suggested that these postulates have been fulfilled for H pylori and gastric cancer[103], however, no studies to date have specifically undertaken or successfully proven Koch’s postulates using animal models. It appears that these statements are not based on the strict adherence to these postulates of causation, but rather that ‘sometimes’H pylori is associated with gastric cancer.

The agent must be recovered from the experimental disease produced. It is not always possible to isolate H pylori organisms from gastric cancer tissue whether this be from humans or animals[104]. This is due to the histopathological changes that occur which decrease the ability of H pylori to adhere to the stomach and thus over time leads to a decreased antibody response[93,105,106].

Currently, the epidemiological data are conflicting on the relationship between H pylori and gastric cancer. The independent meta-analyses provide an overall consensus that H pylori infection is associated with an increased risk (approximately a two-fold increased risk) of developing gastric cancer even though 50% of the studies have produced negative findings. However, there is still a lack of ‘cause and effect’ evidence concerning this relationship, which requires further animal and epidemiological studies to determine the possible carcinogenic mechanisms by which H pylori might cause gastric cancer. One of the major problems in determining a true causal association with H pylori and a disease is related to its high world-wide prevalence making associations with many conditions possible. Only strict adherence to Bradford Hill’s criteria, Henle-Koch’s and/or Evan’s postulates ensures that cause-and-effect relationships are correctly identified. Prevention studies in the form of H pylori eradication randomised placebo controlled trials among gastric cancer patients are currently being conducted.

I would like to dedicate this manuscript to Professor Barry Marshall and Emeritus Professor Robin Warren who were awarded the 2005 Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology for their discovery of H pylori. This finding changed many of our lives and made the practice of clinical gastroenterology more challenging and gastrointestinal research more extraordinary, with advances in numerous areas of medicine (New Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2421-2423).

The author thanks Dr J. Danesh and Dr Jia-Qing Huang for providing information regarding their meta-analysis papers.

| 1. | Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;1:1273-1275. [PubMed] |

| 2. | McNulty CA. The discovery of Campylobacter-like organisms. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1999;241:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Allen P. What's the story H. pylori. Lancet. 2001;357:694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schistosomes , liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7-14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1-241. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kuipers EJ, Gracia-Casanova M, Peña AS, Pals G, Van Kamp G, Kok A, Kurz-Pohlmann E, Pels NF, Meuwissen SG. Helicobacter pylori serology in patients with gastric carcinoma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:433-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Estevens J, Fidalgo P, Tendeiro T, Chagas C, Ferra A, Leitao CN, Mira FC. Anti-Helicobacter pylori antibodies prevalence and gastric adenocarcinoma in Portugal: report of a case-control study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1993;2:377-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Webb PM, Yu MC, Forman D, Henderson BE, Newell DG, Yuan JM, Gao YT, Ross RK. An apparent lack of association between Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of gastric cancer in China. Int J Cancer. 1996;67:603-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim HY, Cho BD, Chang WK, Kim DJ, Kim YB, Park CK, Shin HS, Yoo JY. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric cancer among the Korean population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:100-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Crespi M, Citarda F. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: an overrated risk. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:1041-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Watanabe T, Tada M, Nagai H, Sasaki S, Nakao M. Helicobacter pylori infection induces gastric cancer in mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:642-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 678] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Farinha P, Gascoyne RD. Helicobacter pylori and MALT lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1579-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | HILL AB. THE ENVIRONMENT AND DISEASE: ASSOCIATION OR CAUSATION. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295-300. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Koch R. Die Aetiologie der Tuberkulose. Berl Klin Wochenschr. 1882;19:221-230. |

| 14. | Evans AS. Causation and disease: a chronological journey. The Thomas Parran Lecture. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:249-258. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 623] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Last JM. Dictionary of Epidemiology. 4th ed. UK: Oxford University Press 2001; . |

| 17. | Eslick GD, Lim LL, Byles JE, Xia HH, Talley NJ. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2373-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Danesh J. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer: systematic review of the epidemiological studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:851-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kikuchi S, Wada O, Nakajima T, Nishi T, Kobayashi O, Konishi T, Inaba Y. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody and gastric carcinoma among young adults. Research Group on Prevention of Gastric Carcinoma among Young Adults. Cancer. 1995;75:2789-2793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Eslick GD, Yan P, Xia HH, Murray H, Spurrett B, Talley NJ. Foetal intrauterine growth restrictions with Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1677-1682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kountouras J, Mylopoulos N, Boura P, Bessas C, Chatzopoulos D, Venizelos J, Zavos C. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:599-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gasbarrini A, Massari I, Serricchio M, Tondi P, De Luca A, Franceschi F, Ojetti V, Dal Lago A, Flore R, Santoliquido A. Helicobacter pylori eradication ameliorates primary Raynaud's phenomenon. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1641-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Monstein HJ, Jonsson Y, Zdolsek J, Svanvik J. Identification of Helicobacter pylori DNA in human cholesterol gallstones. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:112-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tunca A, Türkay C, Tekin O, Kargili A, Erbayrak M. Is Helicobacter pylori infection a risk factor for migraine A case-control study. Acta Neurol Belg. 2004;104:161-164. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Xia HH, Talley NJ, Kam EP, Young LJ, Hammer J, Horowitz M. Helicobacter pylori infection is not associated with diabetes mellitus, nor with upper gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes mellitus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1039-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Aceti A, Are R, Sabino G, Fenu L, Pasquazzi C, Quaranta G, Zechini B, Terrosu P. Helicobacter pylori active infection in patients with acute coronary heart disease. J Infect. 2004;49:8-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | El Miedany YM, Baddour M, Ahmed I, Fahmy H. Sjogren's syndrome: concomitant H. pylori infection and possible correlation with clinical parameters. Joint Bone Spine. 2005;72:135-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Reinauer S, Megahed M, Goerz G, Ruzicka T, Borchard F, Susanto F, Reinauer H. Schönlein-Henoch purpura associated with gastric Helicobacter pylori infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:876-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tomasi PA, Dore MP, Fanciulli G, Sanciu F, Realdi G, Delitala G. Is there anything to the reported association between Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune thyroiditis. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:385-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Caselli M, Zaffoni E, Ruina M, Sartori S, Trevisani L, Ciaccia A, Alvisi V, Fabbri L, Papi A. Helicobacter pylori and chronic bronchitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:828-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Pierantozzi M, Pietroiusti A, Galante A, Sancesario G, Lunardi G, Fedele E, Giacomini P, Stanzione P. Helicobacter pylori-induced reduction of acute levodopa absorption in Parkinson's disease patients. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:686-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Altschuler E. Gastric Helicobacter pylori infection as a cause of idiopathic Parkinson disease and non-arteric anterior optic ischemic neuropathy. Med Hypotheses. 1996;47:413-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F. Does H. Pylori infection play a role in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and in other autoimmune diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1271-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Gedik GK, Karaduman A, Sivri B, Caner B. Has Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy any effect on severity of rosacea symptoms. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:398-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Rigopoulos D, Katsambas A, Karalexis A, Papatheodorou G, Rokkas T. No increased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yang YJ, Sheu BS, Lee SC, Yang HB, Wu JJ. Children of Helicobacter pylori-infected dyspeptic mothers are predisposed to H. pylori acquisition with subsequent iron deficiency and growth retardation. Helicobacter. 2005;10:249-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Richter T, Richter T, List S, Müller DM, Deutscher J, Uhlig HH, Krumbiegel P, Herbarth O, Gutsmuths FJ, Kiess W. Five- to 7-year-old children with Helicobacter pylori infection are smaller than Helicobacter-negative children: a cross-sectional population-based study of 3,315 children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33:472-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bravo LE, Mera R, Reina JC, Pradilla A, Alzate A, Fontham E, Correa P. Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on growth of children: a prospective cohort study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:614-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rosenstock SJ, Jørgensen T, Andersen LP, Bonnevie O. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with lifestyle, chronic disease, body-indices, and age at menarche in Danish adults. Scand J Public Health. 2000;28:32-40. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Zullo A, Hassan C, Morini S. Hepatic encephalopathy and Helicobacter pylori: a critical reappraisal. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:164-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Cremonini F, Gabrielli M, Gasbarrini G, Pola P, Gasbarrini A. The relationship between chronic H. pylori infection, CagA seropositivity and stroke: meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2004;173:253-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Gasbarrini A, Carloni E, Gasbarrini G, Chisholm SA. Helicobacter pylori and extragastric diseases--other Helicobacters. Helicobacter. 2004;9 Suppl 1:57-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Strachan DP. Non-gastrointestinal consequences of Helicobacter pylori infection. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:87-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Patal P, Gasbarrini G, Pretolani S, Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F. Extradigestive diseases and Helicobacter pylori infection. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 1997;13:52-55. |

| 45. | Leontiadis GI, Sharma VK, Howden CW. Non-gastrointestinal tract associations of Helicobacter pylori infection. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:925-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Realdi G, Dore MP, Fastame L. Extradigestive manifestations of Helicobacter pylori infection: fact and fiction. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:229-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Israel DA, Peek RM. pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1271-1290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Baldari CT, Lanzavecchia A, Telford JL. Immune subversion by Helicobacter pylori. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:199-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Houghton J, Wang TC. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: a new paradigm for inflammation-associated epithelial cancers. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1567-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Genta RM. Helicobacter pylori, inflammation, mucosal damage, and apoptosis: pathogenesis and definition of gastric atrophy. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:S51-S55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Ernst PB, Gold BD. The disease spectrum of Helicobacter pylori: the immunopathogenesis of gastroduodenal ulcer and gastric cancer. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:615-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Mitchell HM, Bohane TD, Tobias V, Bullpitt P, Daskalopoulos G, Carrick J, Mitchell JD, Lee A. Helicobacter pylori infection in children: potential clues to pathogenesis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;16:120-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Eslick GD. Pregnant women and the Helicobacter pylori generation effect. Helicobacter. 2003;8:643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Banatvala N, Mayo K, Megraud F, Jennings R, Deeks JJ, Feldman RA. The cohort effect and Helicobacter pylori. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:219-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Harvey RF, Spence RW, Lane JA, Nair P, Murray LJ, Harvey IM, Donovan J. Relationship between the birth cohort pattern of Helicobacter pylori infection and the epidemiology of duodenal ulcer. QJM. 2002;95:519-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Roosendaal R, Kuipers EJ, Buitenwerf J, van Uffelen C, Meuwissen SG, van Kamp GJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM. Helicobacter pylori and the birth cohort effect: evidence of a continuous decrease of infection rates in childhood. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1480-1482. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Pollak PT, Best LM, Bezanson GS, Marrie T. Increasing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection with age: continuous risk of infection in adults rather than cohort effect. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:434-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Camargo MC, Yepez MC, Ceron C, Guerrero N, Bravo LE, Correa P, Fontham ET. Age at acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection: comparison of two areas with contrasting risk of gastric cancer. Helicobacter. 2004;9:262-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Xia HH, Talley NJ. Natural acquisition and spontaneous elimination of Helicobacter pylori infection: clinical implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1780-1787. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Gisbert JP. The recurrence of Helicobacter pylori infection: incidence and variables influencing it. A critical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2083-2099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Virchow R. Cellular Pathology. London: John Churchill 1860; . |

| 62. | Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow. Lancet. 2001;357:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5245] [Cited by in RCA: 5854] [Article Influence: 234.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 63. | Hussain SP, Hofseth LJ, Harris CC. Radical causes of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:276-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1242] [Cited by in RCA: 1209] [Article Influence: 52.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Moss SF, Blaser MJ. Mechanisms of disease: Inflammation and the origins of cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:90-97; quiz 1 p following 113. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Pisani P, Parkin DM, Muñoz N, Ferlay J. Cancer and infection: estimates of the attributable fraction in 1990. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:387-400. [PubMed] |

| 66. | EPSTEIN MA, ACHONG BG, BARR YM. VIRUS PARTICLES IN CULTURED LYMPHOBLASTS FROM BURKITT'S LYMPHOMA. Lancet. 1964;1:702-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1823] [Cited by in RCA: 1729] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | M'Fadyan J, Hobday F. Note on the experimental "transmission of warts in the dog". J Comp Pathol Ther. 1898;11:341-343. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Ferri C, La Civita L, Zignego AL, Pasero G. Viruses and cancers: possible role of hepatitis C virus. Eur J Clin Invest. 1997;27:711-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Kew MC. The hepatitis B virus and the genesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. GI Cancer. 1996;1:143-148. |

| 70. | Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, Moore PS. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865-1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4341] [Cited by in RCA: 4180] [Article Influence: 130.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 71. | Welton JC, Marr JS, Friedman SM. Association between hepatobiliary cancer and typhoid carrier state. Lancet. 1979;1:791-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Ferguson AR. Associated bilharziasis and primary malignant disease of the urinary bladder, with observations in a series of forty cases. J Path Bacteriol. 1911;16:76-94. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Yamaguchi N, Kakizoe T. Synergistic interaction between Helicobacter pylori gastritis and diet in gastric cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Xia HH, Wong BC. Nitric oxide in Helicobacter pylori-induced apoptosis and its significance in gastric carcinogenesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:1227-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Yuasa Y. Control of gut differentiation and intestinal-type gastric carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:592-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Peek RM, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:28-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1317] [Cited by in RCA: 1354] [Article Influence: 56.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 77. | Xia HH, Talley NJ. Apoptosis in gastric epithelium induced by Helicobacter pylori infection: implications in gastric carcinogenesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:16-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Tajima K. Challenging epidemiological strategy for paradoxical evidence on the risk of gastric cancer from Helicobacter pylori infection. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2002;32:275-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Available from: http://new.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2009/Training%20for%20trainers%20on%20Cancer%20Registration%20and%20data%20evaluation_IARC.pdf. |

| 80. | Lunet N, Barros H. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer: facing the enigmas. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:953-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Louw JA, Kidd MS, Kummer AF, Taylor K, Kotze U, Hanslo D. The relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection, the virulence genotypes of the infecting strain and gastric cancer in the African setting. Helicobacter. 2001;6:268-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Masci E, Viale E, Freschi M, Porcellati M, Tittobello A. Precancerous gastric lesions and Helicobacter pylori. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:854-858. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Genta RM, Gürer IE, Graham DY, Krishnan B, Segura AM, Gutierrez O, Kim JG, Burchette JL Jr. Adherence of Helicobacter pylori to areas of incomplete intestinal metaplasia in the gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1206-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Osawa H, Inoue F, Yoshida Y. Inverse relation of serum Helicobacter pylori antibody titres and extent of intestinal metaplasia. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:112-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Shimizu N, Ikehara Y, Inada K, Nakanishi H, Tsukamoto T, Nozaki K, Kaminishi M, Kuramoto S, Sugiyama A, Katsuyama T. Eradication diminishes enhancing effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on glandular stomach carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1512-1514. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, Lai KC, Hu WH, Yuen ST, Leung SY. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1015] [Cited by in RCA: 1052] [Article Influence: 47.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Parsonnet J, Forman D. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer--for want of more outcomes. JAMA. 2004;291:244-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Kamada T, Hata J, Sugiu K, Kusunoki H, Ito M, Tanaka S, Inoue K, Kawamura Y, Chayama K, Haruma K. Clinical features of gastric cancer discovered after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori: results from a 9-year prospective follow-up study in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1121-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Dixon MF. Prospects for intervention in gastric carcinogenesis: reversibility of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. Gut. 2001;49:2-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Genta RM. Screening for gastric cancer: does it make sense. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 2:42-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Mc Loughlin RM, Sebastian SS, O'Connor HJ, Buckley M, O'Morain CA. Review article: test and treat or test and scope for Helicobacter pylori infection. Any change in gastric cancer prevention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17 Suppl 2:82-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Xue FB, Xu YY, Wan Y, Pan BR, Ren J, Fan DM. Association of H. pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a Meta analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:801-804. [PubMed] |

| 93. | Axon A. Review article: gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16 Suppl 4:83-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 94. | Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, Irvine EJ, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1636-1644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Forman D. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinogenesis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1992;4 suppl 2:S31-S35. |

| 96. | Shimizu N, Inada K, Nakanishi H, Tsukamoto T, Ikehara Y, Kaminishi M, Kuramoto S, Sugiyama A, Katsuyama T, Tatematsu M. Helicobacter pylori infection enhances glandular stomach carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils treated with chemical carcinogens. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:669-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Sugiyama A, Maruta F, Ikeno T, Ishida K, Kawasaki S, Katsuyama T, Shimizu N, Tatematsu M. Helicobacter pylori infection enhances N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced stomach carcinogenesis in the Mongolian gerbil. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2067-2069. [PubMed] |

| 98. | Tokieda M, Honda S, Fujioka T, Nasu M. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on the N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine-induced gastric carcinogenesis in mongolian gerbils. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1261-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Honda S, Fujioka T, Tokieda M, Satoh R, Nishizono A, Nasu M. Development of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinoma in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4255-4259. [PubMed] |

| 100. | Hirayama F, Takagi S, Iwao E, Yokoyama Y, Haga K, Hanada S. Development of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and carcinoid due to long-term Helicobacter pylori colonization in Mongolian gerbils. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:450-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Marshall BJ, Armstrong JA, McGechie DB, Glancy RJ. Attempt to fulfil Koch's postulates for pyloric Campylobacter. Med J Aust. 1985;142:436-439. [PubMed] |

| 102. | Marshall BJ, McGechie DB, Rogers PA, Glancy RJ. Pyloric Campylobacter infection and gastroduodenal disease. Med J Aust. 1985;142:439-444. [PubMed] |

| 103. | Wang TC, Fox JG. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: Koch's postulates fulfilled. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:780-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Weaver A, DiMagno EP, Carpenter HA, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Gastric adenocarcinoma and Helicobacter pylori infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1734-1739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Wang JT, Chang CS, Lee CZ, Yang JC, Lin JT, Wang TH. Antibody to a Helicobacter pylori species specific antigen in patients with adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:360-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Janulaityte-Günther D, Kupcinskas L, Pavilonis A, Valuckas K, Percival Andersen L, Wadström T. Helicobacter pylori antibodies and gastric cancer: a gender-related difference. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;44:191-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Pan BR L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Ma WH