INTRODUCTION

Evaluation of the biliary tract is of importance in physiological, pathophysiological, and clinical settings. Clinical investigations in patients with well-defined, organic diseases such as gallstones, is outside the scope of this review, where focus is directed towards patients with functional biliary symptoms. Investigations aiming at morphological alterations in the biliary tract are thus not discussed in this paper.

The value of different investigative methods is often fluid: Some methods are used to render probable or document a correlation between symptoms and measurable abnormalities. Others are, or later become, real tools in the diagnostic process of patients with functional biliary symptoms. The methods can roughly be subdivided into two subgroups: Motility investigations, and methods for the evaluations of the sensory conditions. Motility comprises direct measurement of the biliary tract as well as intraluminal transport. A further evaluation of wall characteristics, e.g. by means of impedance planimetry, has, so far, only been conducted in animal experiments[1].

The present review will start with a physiologic background section, followed by a description of patients with functional biliary symptoms and evaluation methods in these patients.

PHYSIOLOGIC BACKGROUND

The function of the biliary tract is to store, concentrate, and transport bile from the liver into the duodenum. In order to accomplish this function the extrabiliary tract is composed of a ductal system, a gallbladder, and a sphincter (Sphincter of Oddi) at the termination of the common bile duct. Previously it was believed that there was an additional sphincteric structure at the junction site of the gallbladder and the cystic duct but studies have failed to prove this supposition. Smooth muscles are present in the gallbladder and in the Sphincter of Oddi (SO). Unlike previous belief, no-or only insignificant-musculature is seen in the ducts. Active contractility is therefore only possible in the gallbladder and the SO. Bile flow into the duodenum occurs after food intake, and late in the interdigestive phase II of the duodenum[2]. The main initiator of biliary secretion-apart from bile production of the liver-is the release of the peptide cholecystokinin (CCK). This peptide relaxes the SO and contracts the gallbladder. The effect of CCK on the SO is brought about by a stimulatory action on inhibitory neurons. This effect overrides a direct stimulatory action of CCK on the SO muscles[3]. In addition to the CCK effect, a reflex relationship exists between the gallbladder and the SO, i.e. pressure increase within the gallbladder leads to relaxation of the SO (Figure 1)[4,5]. This implies that gallbladder contraction, e.g. after food intake, allows bile to run from the gallbladder into the ductal system, and further into the duodenum through the relaxed SO. Conversely, when the gallbladder is empty, the gallbladder pressure is low, and the SO actively contracts, thus allowing bile to divert into the gallbladder. A similar reflex relation is seen between the common bile duct and the SO[6]. This is important in post-cholecystectomy patients.

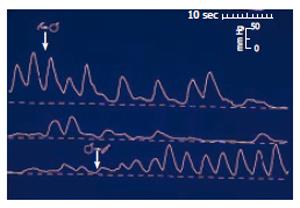

Figure 1 Sphincter of Oddi manometry in a dog during gallbladder distension (upper tracing), and gallbladder emptying (lower tracing).

Distension of the gallbladder-mimicking gallbladder contraction -leads to relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi thus permitting free flow of bile into the duodenum. (After reference 5 with permission).

The gallbladder receives nerve fibres from the sympathetic and the parasympathetic systems. In addition there are a number of neurones containing peptides, e.g. CCK, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), nitric oxide (NO), and motilin. The sympathetic nerves arise at the Th8-9 level and are relayed in the celiac plexus, with second order fibres travelling along the vascular system to the gallbladder. The parasympathetic innervation arises from both the anterior and posterior vagal trunks and reaches the gallbladder in a similar way as the sympathetic fibres, with the exception that branches from the anterior vagal nerve do not pass through the celiac plexus. Vagal activity stimulates gallbladder contraction directly, and enhances the contractile effect of CCK on the gallbladder. Sympathetic activity has the opposite effect on gallbladder motility. The sympathetic system also transmits sensory inputs to the central nervous system leading to pain. Pain is enhanced by inflammation. The ductal system and the sphincter of Oddi (SO) are innervated in a similar way as the gallbladder, with the highest neural density in the SO.

FUNCTIONAL BILIARY PAIN

Biliary pain is mainly characterized according to the symptomatic presentation of gallstone attacks. As in many other gastrointestinal disorders this is not simple, as a variation in symptomatic presentations can be seen in some patients[7]. Nevertheless, according to the existing literature, and the experience of experts, functional biliary pain was defined as absence of demonstrable organic substrate, and[8]: Episodes of severe steady pain located in the epigastrium and right upper quadrant. A number of additional criteria are outlined. One of these is that the pain attack should last at least 30 min. This seems substantiated in patients where the symptoms are derived from the gallbladder. However, if symptoms originate in the SO, this criterion will still await validation. Two types of functional biliary pain syndromes have been described: Gallbladder dysfunction and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD). The symptomatic presentation seems rather similar, but obviously patients with gallbladder dysfunction still have the gallbladder in situ, whereas SOD dysfunction most often-albeit not unequivocally-is seen in post-cholecystectomy patients.

Gallbladder dysfunction

Gallbladder dysfunction denominates a condition where the gallbladder empties insufficiently in a patient with biliary symptoms, without demonstrable organic substrate, such as gallstones. The prevalence of biliary-type pain without gallstones was found to be 2.4%[9]. Other population studies have found prevalences as high as 7.6% in men[10] and 20.3% in women[11]. Per definition patients with gallbladder dysfunction have impaired gallbladder emptying. Later in this paper the methodology is described. The mechanism of pain is rather obscure: Generally it is believed that some kind of functional obstruction at the transition zone between the gallbladder and the cystic duct exists, leading to gallbladder pressure increase. Possibly, a combination with inflammation amplifies sensory firing. Primary hypersensitivity can also not be ruled out and central neuroplastic changes may be responsible for visceral hypersensitivity. Nevertheless, in a randomised controlled investigation[12], it was shown that patients with gallbladder dysfunction would benefit from cholecystectomy. A number of other papers have supported this finding[13,14]. However, there are still a number of critical issues to be addressed[15].

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

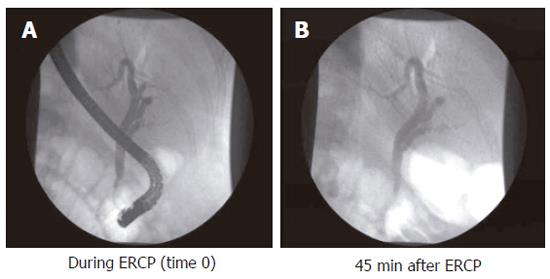

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) denominates patients with biliary-type pain and dysfunction of the Sphincter of Oddi. The condition is most often seen in post-cholecystectomy patients. The prevalence of symptoms suggesting SO dysfunction is about 1.5% after cholecystectomy, being more frequent in women[16]. SO dysfunction can be subdivided into three groups according to clinical presentation, laboratory results, and ERCP findings[17]: (1) Patients with type I SO dysfunction have biliary-like pain, elevated liver function tests documented on two or more occasions, delayed contrast drainage (more than 45 min, (Figure 2), and a common bile duct diameter equal to or greater than 12 mm at ERCP; (2) Type II patients present with biliary-like pain, and only one or two of the above mentioned criteria; (3) Type III patients only have biliary-like pain, and none of the above mentioned criteria. The mechanism of pain is also rather obscure in this group of patients. From a theoretical point of view SO abnormalities could give rise to pain due to impeded flow, ischemia arising from spastic contractions, and hypersensitivity of the papilla or the common bile duct. These mechanisms may solely or in combination explain the genesis of pain[18]. In a prospective randomised study it was shown that pain could be alleviated by endoscopic sphincterotomy[17].

Figure 2 Endoscopic cholangiogram during investigation, and 45 min after contrast injection in a patient with complete contrast retention.

EVALUATION METHODS

Quantitative hepatobiliary scintigraphy

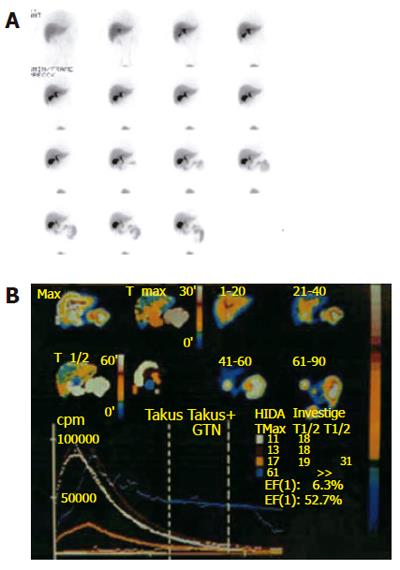

Quantitative hepatobiliary scintigraphy (QHBS) is a non-invasive scintigraphic method where it is possible not only to assess the patency of the biliary system but also to measure the rate of bile flow (Figure 3). 99mTc-N-2,6-dimethylphenylcarbamoylmethyliminodiacetic acid (99mTc-EHIDA) and numerous of its analogues, such as 2, 6-diisopropyliminodiacetic acid (DISIDA) and 2, 4, 6-trimethyl-3-bromoiminodiacetic acid (mebrofenin) are the tracers most widely used for hepatobiliary imaging. After (iv) injection, these 99mTc agents bind loosely to serum proteins and are then rapidly taken up by the hepatocytes and excreted into the bile. This uptake mechanism is similar to that of bilirubin, and hyperbilirubinaemia therefore has an inhibitory effect. After excretion by the hepatocytes, the bile continues to flow into the bile canaliculi, the bile ducts and the gallbladder, and then empties into the duodenum through the SO.

Figure 3 Hepatobiliary scintigraphy.

A: Pictures at different time windows; B: Time activity curves are shown for different regions of interest.

Patients should be fasted for a minimum of 4 h prior to the investigation. The gamma-camera is positioned over the right upper abdomen of the supine patient. After an iv bolus injection of 140-180 MBq 99mTc-IDA derivative, gamma-camera images are acquired on a computer (1 frame/min) for 90-120 min. If needed, analogue images can also be obtained every 10 min for the first hour, with delayed images if required (first image 500 000 counts, and then subsequent images for the same length of time). The analogue pictures should be examined for liver radiotracer uptake, size, shape and homogeneity. Under normal circumstances the liver uptake of 99mTc-IDA compounds is rapid, with little if any tracer in the blood pool by 5 min. In most normal fasting subjects, radioactivity appears in the gallbladder (GB) and in the small bowel by 1 h after its administration. The extent of visualisation of the hepatic ducts is variable but the left duct tends to be more prominent than the right. In patients without extrahepatic bile duct obstruction, the level of radioactivity of the common bile duct (CBD) reaches its maximum before 45 min. Excretion of radioactivity into the duodenum occurs by 60 min in 81% of patients with the GB in situ. In the remaining 19% of patients without bowel activity at 60 min, duodenal visualisation is always present after exogenous CCK administration[19].

Gallbladder phase imaging

The GB contraction after consumption of a meal or administration of an exogenous CCK analogue (CCK octapeptide or caerulein) can also be measured by means of QHBS. These data can be acquired in a separate study between 60 and 90 min after the initial isotope administration. QHBS combined with administration of a meal or an exogenous CCK analogue is a validated and accurate method for the measurement of GB motility, with satisfactory reproducibility of both parametric variables and emptying patterns. The method of measuring GB is to place a region of interest (ROI) over the GB with a ROI over the liver background (adjacent to the GB), then to generate a time-activity curve for the GB and to calculate the GB ejection fraction (EF) via the following formula: EF% = (GBmax-GBmin)/GBmax × 100. The degree of GB emptying is CCK dose-dependent, and therefore the mode of administration has a critical effect on the net GB contraction. The GB EF increases as the dose of CCK is increased from 0.5 to 3.3 ng/kg per minute. Then begins to decrease when larger doses are infused, especially when CCK is given as a rapid iv bolus. A large non-physiological dose produces a low EF in association with abdominal pain, even in normal subjects. It has become clear that the GB EFs obtained depend on the procedure used but a GB EF over 35%[12,20,21] can be regarded as indicative of a normal GB function if it is evoked by a total infusion dose of 10 ng/kg CCK, administered during 3-10 min.

Scintigraphic features of gallbladder dysfunction

In clinical practice, the distinctive feature of a GB dysfunction is impaired GB emptying. A GB EF under 35% is a sensitive test for the identification of patients with chronic cholecystitis or GB dysfunction[12,20,21]. However, there is a considerable overlap in EF values[15]. Many of the patients experience a reproduction of biliary pain during CCK infusion. Administration of nitro-glycerine before CCK infusion can abolish biliary pain and normalise the GBEF in a subset of patients with gallbladder dysfunction.

Scintigraphic features of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

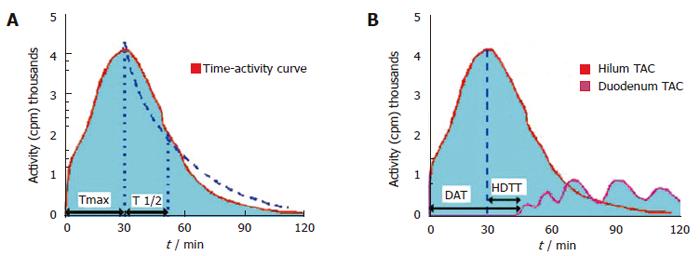

The scintigraphic signs in SOD depend upon the presence or absence of a GB in situ, albeit the latter is rare. In patients with SOD and GB in situ, an intact GB serves as a low-pressure reservoir by compensating the increased bile flow that is diverted into it by the tight and hypertonic SO. Therefore, the CBD does not dilate and the rate of emptying of the isotope from the CBD is usually in the normal range. After CCK administration to patients with a functional SOD, the SO relaxes (except in SOD patients with a paradoxical response to CCK, which is a relatively rare phenomenon) and, if the GB function is intact, the GB EF remains normal. In cholecystectomized subjects with a normal liver function, the flow of the bile from the liver to the duodenum is mainly regulated by the motor activity of the SO. HIDA compounds, which are taken up and secreted by the liver into the bile, can therefore be used as markers to measure the rate of bile flow and indirectly to assess the patency of the SO. In asymptomatic cholecystectomized patients with a normal SO function, HIDA excretion and transit from the liver into the duodenum is rapid, and the time-activity curves are exponential, exhibiting only minor patient-to-patient variations[19]. In cholecystectomized patients with SOD however, cholescintigraphy reveals a prominent bile stasis within the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts, and a marked delay in the transpapillary isotope transit[22-24]. Retention of a 99mTc-IDA tracer after 120 min in the visually prominent bile ducts on static images of the planar HBS was noted to be a good predictor of an abnormal biliary drainage. Quantitative cholescintigraphic parameters may afford valuable numerical information on the bile flow impairment in the presence of a SOD, thereby increasing the sensitivity (Figure 4). Unfortunately, it is not clear, which scintigraphic variable is optimal to express SOD. We recently compared the sensitivities of these parameters in cholecystectomized patients with SOD diagnosed by manometry, which showed that HDTT was the best predictor of SOD, followed by DAT, and then the T1/2 parameters of the hepatic hilum and CBD Madacsy). The quantitative parameters of the CBD seem to be relatively insensitive, which is probably due to the disturbing influence of other factors, such as the CBD diameter and the duodenal motility phase during the study. In fact, we found that the SO basal pressure relative to the CBD pressure exhibited the best correlation with the QHBS parameters. CCK administration increases the hepatic bile secretion and relaxes the SO; it therefore washes out the bile stasis from the ducts if there is no anatomic obstruction. A differentiation between a fixed anatomic obstruction (organic SO stenosis, bile duct stricture or stones, etc.) and a functional obstruction (SO spasm) can also be made by amyl nitrate or nitro-glycerine administration during QHBS. In order to measure SO relaxation after the administration of a smooth muscle relaxant in patients with SOD, after the baseline evaluation of the QHBS parameters, at 60 min amyl nitrate was administered and the T1/2 parameter of the CBD was recalculated. A reversible biliary obstruction on the QHBS (an obstructive pattern relieved after amyl nitrate) indicates a functional SOD, i.e. an SO spasm, whereas a persistent accumulation of the isotope in the biliary tree (during the baseline condition and after amyl nitrate) suggests a fixed organic obstruction[25]. A differentiation between stenosis and dyskinesia of the SO may be important from a clinical point of view, and it might modify the therapeutic strategy, since endoscopic sphincterotomy is of great benefit in patients with a persistently elevated basal SO pressure and SO stenosis. To summarise, QHBS may be regarded as a useful method for study of the bile flow dynamics in patients with postcholecystectomy syndrome and suspected SOD. QHBS may be applied not only as a simple and non-invasive screening test before SO manometry but also as a reliable diagnostic method during the evaluation and follow-up of patients with suspected SOD.

Figure 4 Hepatobiliary scintigraphic activity curves of regions of interest in sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

Ultrasonography

US has become a widely used method for visualisation of the abdominal organs. As it is a non-invasive method without radiation exposure, it has also become a popular method for the investigation of motility disorders of the GB and the SO. US methods are relatively cheap and widely available and they also afford excellent reproducibility and sensitivity. However, their diagnostic accuracy is appreciably investigator-dependent and also influenced by the different forms of methodology.

Ultrasonographic measurement of GB contraction

The GB contraction induced by exogenous CCK or CCK analogue (caerulein) administration can be measured by means of either US or QHBS, but methods involving QHBS are currently regarded as the gold standard. QHBS offers the advantage over US of allowing simultaneous visualisation of the bile ducts, together with non-geometrical measurement of the GB contraction. However, the lack of radiation exposure is a favourable feature of the US methods, because it can be repeated several times in the same patient, which is extremely important in motility studies if normal physiology is investigated. US is also able to determine the approximate volume of the GB, which may be of some importance in the pathophysiology of GB motility. Different formulae are known for calculation of the GB volume. The most widely used is the sum of cylinders method, or Dodd’s formula. With this method, the GB volume (GBV) can be calculated if one multiplies the three axes together and then by Pi/6[26]. The GB EF is calculated from the fasting and post-stimulation GBVs via the well-known formula: GBEF (%) = GBVmax - GBVmin/GBVmax. The refilling of the GB is another characteristic feature of GB motility, which can be calculated as a percentage of the ratio between the GBV in the most contracted state and at the maximum after refilling. The two main types of stimuli, which can be used to evoke GB contraction, are food intake and administration of CCK or a CCK analogue.

Ultrasonographic bile duct imaging

Bile duct imaging with US is more difficult than visualisation of the GB. Most investigators use the right anterior oblique view to visualise the common hepatic duct within the porta hepatis, where the surrounding liver parenchyma gives a good acoustic window. Visualisation of the pancreatic duct in the body of the pancreas may be problematic in a number of patients, because the presence of gas in the stomach and in the intestines above it means that an acoustic window is not available. Moreover, exact determination of the pancreatic duct diameter necessitates its measurement in two different part of the pancreas. The upper limit of normal diameter of the common hepatic duct (also termed hepatocholedochus, because it is not possible to differentiate between common hepatic duct and CBD by US) is less than 8-10 mm, and of the pancreatic duct is less than 2-3 mm.

Ultrasonographic assessment of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

Ultrasonography has been reported as a method for diagnosing SO dysfunction. The authors measured the bile duct diameter before and after CCK infusion or ingestion of a fatty meal[27,28]. However, these methods have not gained acceptance, probably because of low reproducibility.

Sphincter of Oddi manometry

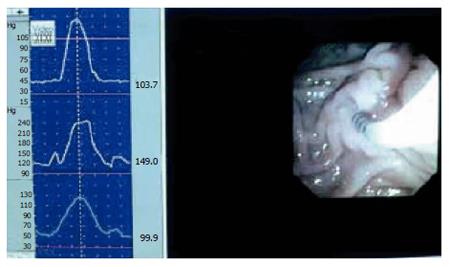

SO manometry can be done during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatographic (ERCP) investigation. A triple lumen catheter with sideholes spaced 2 mm apart is introduced into the common bile duct, and then withdrawn until positioned in the SO segment. The catheter is slowly perfused from a hydraulic capillary infusion pump, and external transducers are connected with a computer for direct reading of the manometric tracing. Additionally the readings are stored for later analysis[29,30]. The SO is a high-pressure zone with an elevated baseline and superimposed phasic contractions. The readings may suffer from periodic superimposed artefact patterns. Usually these are easily recognised, but simultaneous endoscopic videorecording may be helpful in separating SO activity from artefact phenomenon (Figure 5)[31]. The parameters measured are baseline pressure and phasic wave amplitude, duration, frequency, and propagation mode. Baseline pressure is measured with the duodenal pressure as zero reference. The amplitude is measured with baseline pressure as zero reference. When evaluating the propagation modality, proximal and distal readings are compared.

Figure 5 Combined video- and manometric recording in the sphincter of Oddi during endoscopy.

Normal SO manometry

In healthy subjects the baseline pressure is around 5-15 mmHg, phasic wave amplitude 100-140 mmHg, wave duration 4-6 s, and frequency 3-6 waves per minute. Most contractions are coordinated, and the direction of contractions is mostly antegrade, with only 5%-20% being retrograde[32]. After cholecystectomy no significant alterations are seen in patients who no longer have symptoms[33,34].

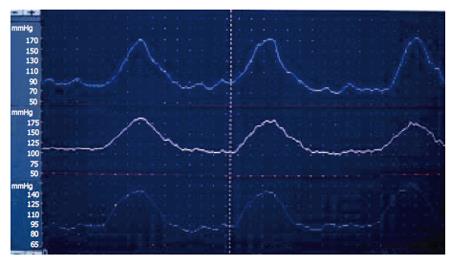

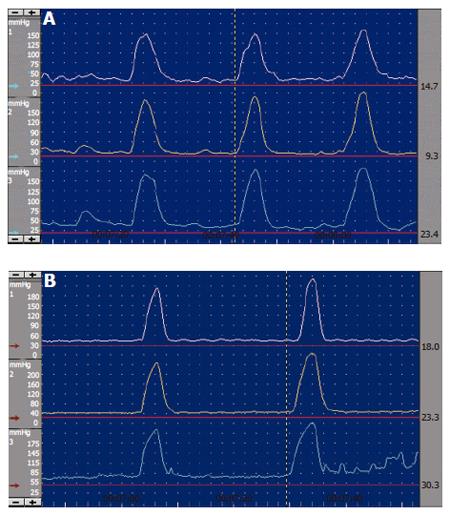

Abnormal SO manometry

SO manometric abnormalities comprise elevated baseline pressure, increased phasic wave amplitude, frequency, and disordered propagation mode (Figure 6, Figure 7). It has been suggested to define SO abnormality as a baseline pressure of more than 40 mmHg, phasic amplitude above 350 mmHg, frequency of more than 7 waves per minute; and a pattern of more than 50% retrograde waves[8]. The clinical importance of these abnormalities is not clear, except for elevated baseline pressure, where it was shown in a randomised study that patients with this abnormality improved clinically after endoscopic sphincterotomy[17].

Figure 6 Endoscopic sphincter of Oddi manometry in a patient with elevated baseline pressure.

Figure 7 Endoscopic sphincter of Oddi manometry.

A: Normal antegrade contractions; B: Abnormal retrograde waves.

Pain studies

The fact that there are still “holes” in our understanding of patients with functional biliary pain has led investigators to focus on sensory mechanisms. Clinically, it has been observed that some patients develop pain upon manipulation with the papilla (tender papilla), or during intraductal contrast injection. A further step forward was taken with the demonstration of duodenal-specific visceral hyperalgesia in post-cholecystectomy patients with persistent abdominal pain[35]. Stawowy et al[36-38] has investigated the referred pain area in patients with uncomplicated gallstones and acute cholecystitis before and after cholecystectomy. Although hypersensitivity was found in both groups of patients, the hypothesized prolonged neuroplastic changes, as a possible explanation of post-cholecystectomy syndrome could not be proven. However, in the future it will be of importance to conduct studies in patients with post-cholecystectomy syndrome and also in patients with suspected gallbladder dysfunction.