Published online May 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2641

Revised: August 13, 2006

Accepted: August 30, 2005

Published online: May 7, 2006

The high prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in Western societies has accelerated the need for new modalities of treatment. Currently, medical and surgical therapies are widely accepted among patients and physicians. New potent antisecretory drugs and the development of minimally invasive surgery for the management of GERD are at present the pivotal and largely accepted approaches to treatment. The minimally invasive treatment revolution, however, has stimulated several new endoscopic techniques for GERD.

Up to now, the data is limited and further studies are necessary to compare the advantages and disadvantages of the various endoscopic techniques to medical and laparoscopic management of GERD. New journal articles and abstracts are continuously being published. The Food and Drug Administration has approved 3 modalities, thus gastroenterologists and surgeons are beginning to apply these techniques. Further trials and device refinements will assist clinicians.

This article will present an overview of the various techniques that are currently on study. This review will report the efficacy and durability of various endoscopic therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The potential for widespread use of these techniques will also be discussed. Articles and abstracts published in English on this topic were retrieved from Pubmed. Due to limited number of studies and remarkable differences between various trials, strict criteria were not used for the pooled data presented, however, an effort was made to avoid bias by including only studies that used off-PPI scoring as baseline and intent to treat.

- Citation: Iqbal A, Salinas V, Filipi CJ. Endoscopic therapies of gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(17): 2641-2655

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i17/2641.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2641

Gastroesophageal reflux disease affects millions of people worldwide. The prevalence of heartburn in a randomly selected adult population is approximately 20%. It is estimated that approximately one third of the adult population in the United States suffers from heartburn[1]. Of these, approximately 7% have reflux esophagitis. The management of GERD has gained increasing attention during the past two decades due to a high prevalence in Western societies, a better understanding of the pathophysiology, new potent anti-secretory drug therapies, the advent of minimally invasive surgery and new transoral endoscopic therapies. We attempt to determine the true efficacy and benefit of these therapies. The relative advantage of one over the other is enlightened by objective comparison of study outcomes. The potential for use by clinicians in daily practice and the underlying mechanisms of action are also explored.

It is important to understand the pathophysiology of GERD although much controversy remains. The efficacy of the antireflux barrier at the GEJ is dependent upon three factors. These include the “lower esophageal sphincter complex”, the geometric profile of the cardia and the changes within each as a result of gastric distension. Other factors such as gravity, intra-peritoneal pressure, esophageal motility and the mucosal barrier also play a role in reflux prevention. Reflux can be precipitated by a decrease in either the length or the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and/or obliteration or diminishment of the angle of His. Both these factors are present during periods of gastric distension. It is believed that transient LES relaxations (tLESR), i.e. intermittent spontaneous decreases in LESP, are responsible for reflux events in patients with a normal LES[2-5]. In the early stages of disease and in the absence of a hiatal hernia, the geometry and integrity of the cardia are normal. However, during periods of gastric distension such as after meals, gastric distension alters the anatomy and makes the sphincter incompetent due to sphincter shortening, which some term transient lower esophageal sphincter shortening (tLESS)[6]. Such patients appear to be the ideal population for endoscopic antireflux procedures.

In the light of the above described pathophysiologic factors, endoscopic therapies should prevent reflux in the following ways; (1) alter the compliance of the cardia and prevent tLES shortening/relaxation, (2) increase baseline LES tone or (3) increase baseline LES length. None of the endoluminal therapies reduce the distal esophagus into the abdomen and effect a hiatal hernia repair.

The majority of patients with GERD are best treated by proton pump inhibitors (PPI’s). However, symptom relapse is common after cessation of treatment[7] and lifelong therapy is often necessary. Even while on therapy, up to 33% of patients have recurrent symptoms within the first two years. Almost 50% of patients continue to exhibit objective evidence of acid regurgitation despite complete symptomatic control on PPI therapy. Although, a fundoplication is a good treatment option[8], laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery requires a general anesthetic, hospitalization, postoperative lifestyle limitations for days to weeks, is expensive and is associated with post-operative morbidity and even a mortality rate. In addition, patients may return to medical therapy[9]. These limitations created the need to develop less invasive but effective procedures. These procedures are listed here (1) Endoscopic Suturing devices: Endoluminal Gastroplication (ELGP/Endocinch); Endoluminal full-thickness plicator (NDO plicator); Syntheon ARD Plicator; (2) Radiofrequency energy delivery device: Stretta; (3) Synthetic Implants/Injections: Implantable biopolymer (Enteryx); Implantable Prosthesis (Gatekeeper); Implantable plexiglass microspheres (PMMA). Of these, 3 novel endoscopic therapies have been approved for use by the FDA. All procedures can be safely performed in an outpatient setting utilizing conscious sedation.

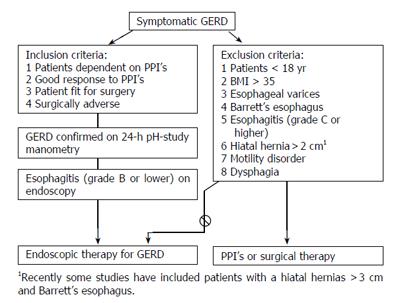

The general selection criteria that have been used in most trials are shown in Figure 1. In addition to this, specific patient selection, if any, is mentioned under the respective procedures.

Initially, Swain et al developed a mechanical aid which allowed passage of a needle and subsequent suture via the biopsy channel of an endoscope[10]. Later, the technique was modified to create plications endoscopically below and at the GEJ for the prevention of GERD.

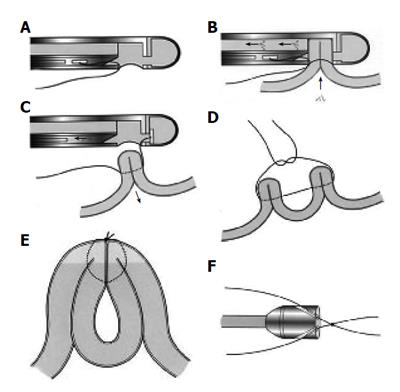

The procedure requires a suturing capsule, suture tags and an anchoring system that secures the suture and cuts the strands (Figure 2). A short, 18 mm-outer-diameter overtube allows repeated intubations (approximately 12) while avoiding trauma to the esophageal mucosa. Usually patients tolerate the procedure with conscious sedation. However monitored anesthesia or general anesthesia may be used as necessary. Two to four plications are placed either longitudinally (one above the other), radially (next to each other) or spirally within the cardia. Each plication is formed by two stitches that are placed into the gastric submucosa, approximately one centimeter apart and then pulled together. The procedure is completed within 40 to 60 minutes.

The application of cautery on opposing mucosal surfaces prior to plication may secure tissue apposition and promote long-term adherence. Its efficacy has been proved in pilot studies[11] and needs to be tested in a larger randomized controlled trial.

The overall results with ELGP are tabulated in Table 1. This is a pooled data obtained from 11 studies. Two multicenter trials are included in the table and will be highlighted. In the first trial 64 patients were randomized between a circumferential and a linear plication configuration[12]. All patients were dependent on anti-secretories and had proven reflux by 24-h pH monitoring. Manometry and endoscopy was performed to exclude patients with Barrett’s esophagus, grade 3 or 4 esophagitis, large hiatal hernias and an esophageal dysmotility disorder. There was no difference found between the plication configuration groups and post-procedure manometry and endoscopy showed no improvement in LES pressure or grade of esophagitis. A significant improvement in heartburn and regurgitation scores from baseline was found but the pH monitoring results although significantly improved showed only a 30% normalization rate.

| Trial result | ELGP | NDO Plicator | Stretta | Enteryx | Gatekeeper1 |

| HDQRL improvement | 55% | 70% | 65% | 70% | 74%1 |

| Heartburn improvement | 74% | - | 61% | 71% | - |

| Off PPI’s | |||||

| At 1 yr | 40% | 75% | 55% | 72% | 58%1 |

| At > 2 yr | 33% | - | 63% | 65% | - |

| ≥ 50% reduction in PPI | 51% | - | 67% | 80% | 54%1 |

| Quality of life improvement | |||||

| SF-36 Physical | 17% | 31% | 20% | 12% | 17%1 |

| SF-36 Mental | None | 10% | 14% | 3% | 1.4%1 |

| Time pH < 4 improvement | 16% | None | 36% | 33% | 32%1 |

| No. of reflux episode improvement | 33% | - | None | 31% | 45%1 |

| pH normalization | 25% | - | - | 38% | 40%1 |

| LESP improvement | None | None | None | None | None |

| LES length improvement | None | None | None | None | None |

| tLESR improvement | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Healing of esophagitis | None | None | None | None | None |

| Sham Trial | 3-mo FU | Being planned | 1-yr FU | Underway | Underway |

In a second multicenter study, 85 symptomatic GERD patients when off PPIs and with proven reflux on 24-h pH monitoring were included[13]. Upper endoscopy and manometry were also performed at baseline. Follow up was scheduled at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo. Symptom scores and medication usage were assessed at each follow up and pH-metry was done at 3 mo follow up. This study was different from others with respect to their inclusion criteria as it included patients with esophagitis grade 3 (n = 10), hiatal hernia >2 cm (n = 9), Barrett’s esophagus (n = 4), failed fundoplication (n = 3) and those with pulmonary symptoms (n = 10). The majority of the patients had 2 plications performed (range, 1-3) and most had a circumferential plication (65%) with the remaining receiving a linear configuration (35%). Twenty-four-mo follow up data demonstrated durable functional improvement and a sustained reduction in anti-secretory medication. Heartburn scores were reduced at both 1 (94%) and 2 yr (78%) follow up. At 2 yr follow up, complete resolution for heartburn was seen in 52% of patients and 77% for patients with regurgitation. Likewise, PPI usage decreased with 69% of patients using <50% of their baseline medication and 41% were completely off PPI’s at 2 yr follow up. The duration and number of esophageal acid exposures at 3-6 mo post-procedure were significantly reduced. There was no change in LES length or pressure when measured at 3 mo.

A sham-controlled, randomized, blinded single institution study (n = 34) is underway and 3 mo follow-up is available[14]. The study nurse and patients were blinded to the procedure performed. An overtube and 2 endoscopes were exchanged in all patients and the conscious sedation dosing was similar. Four circumferential plications were placed when performing the ELGP. At 3 mo follow up, heartburn frequency (69% vs 31%, P = 0.03) and severity (47% vs 17%, P = NS) were improved in patients with ELGP in comparison to those with the sham procedure. A significantly greater number of patients discontinued their daily PPI/H2B (75% vs 25%, P = 0.03) in the plication group. A significant reduction in % time pH < 4 was also observed, however, no difference was seen between groups regarding normalization of pH, median LESP or quality of life. Limitations of this study include a probable type II error, a larger than expected sham effect, inadequate follow-up length and lack of technique standardization. A randomized controlled trial of larger size with longer follow up is needed for objective evidence of durable benefit.

Other studies of note have demonstrated a markedly improved quality of life at one year follow up[15], reduction of the rate of tLESRs by 37% at 6 mo in a single-center study[16], in baboons[17] a significant increase in LES length, and Kadirkamanathan et al reported an increase in intra-abdominal, but not total, length of the LES after placement of three linear plications in dogs[10]. A double blind pilot study with 18 patients randomized to either ELGP alone or ELGP with cautery (10 in cautery group, 8 in no cautery group) showed numerically improved patient plication persistence, decreased esophageal exposure and improved symptoms at 1 year in the cautery group. However, the benefits were not sustained at 2-yr follow up[11]. Plication persistence at 1 year was 37% in the cautery group vs 15% in the no-cautery group. Further studies are required to elucidate the efficacy of cautery with ELGP.

A significant improvement in symptom scores and pH study results has been observed in 19 patients refractory to medications, although, this improvement was less than that seen in other studies[18]. Short term studies suggest that ELGP can be used as an effective salvage procedure for failed surgical fundoplication[19,20], however, this indication requires further study.

The mechanism by which ELGP improves competence of the gastroesophageal junction remains unclear. Feitoza et al demonstrated lack of fusion between the folds when sutures were placed intra-luminally in the stomach of rabbits, irrespective of suture depth[21]. The symptomatic improvement can be explained by a lower volume of refluxate reaching the more “sensitive” proximal esophagus. The decreased volume might signify a decreased frequency of tLESR’s, probably due to scar formation. Secondary scarring may also impair distensibility of the proximal stomach. This when combined with the fact that ELGP has been shown to stimulate localized circular muscle hypertrophy in both humans and animals[22] may lead to an increased basal tensile tone and increased resistance to gastric distension. This explanation does not negate, however, the deleterious effect of the acid within the distal esophagus and the chance for progression to complications such as stricture formation or even Barrett’s esophagus.

Endoluminal gastroplasty is generally safe over long term follow up and free of serious immediate side effects. The major and minor complications are shown in Table 2. Esophageal perforations can occur. Two perforations have been seen so far, one of whom required a thoracotomy and the other hospitalization and antibiotics. To avoid a perforation, which is usually due to placement of a full-thickness suture within the esophageal wall, all stitches and plications should be placed below the squamocolumnar junction. If the suturing capsule needle does not retract after penetrating the tissue, the handle with pusher rod should be disassembled rather than pulling the capsule away from the esophageal wall. Occasionally, the suture loops and locks at the tissue level as the second stitch is being placed. The needle literally goes through a loop and the suture will not slide through the tissue on removal of the endoscope. In this circumstance the suture should be cut with an endoscopic scissors, however, this can be difficult and pull out may be necessary. If tissue accompanies the knot, it should be sent to pathology for frozen section analysis. If the muscularis propria is included within the specimen, an esophagram should be performed followed by hospitalization.

| Variable | Endocinch | NDO Plicator | Stretta | Enteryx | Gatekeeper | |

| Procedure duration (mean) | 68 min | 20 min | 69 min | 33 min | 35-60 min | |

| Personnel required | 1 physician and 2 assistants | 1 physician and 2 assistants | 1 physician and 2 assistants | 1 physician and 2 assistants | 1 physician and 2-3 assistants | |

| Sedation required | Conscious sedation 82% | NA | Conscious sedation 100% | Conscious sedation 100% | NA | |

| Approximate no. of procedures performed | 4000 | NA | 4000 | 2600 | 225 | |

| Major complication | Perforation | 0.08% | 0.00% | 0.13% | 0% | 0.40% |

| Bleeding | 0.05% | NA | 0.05% | 0% | 0% | |

| Hypoxemia | 0.08% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Pleural effusion | 0% | 0% | 0.03% | 0.08% | 0% | |

| Pericardial effusion | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0.08% | 0% | |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 0% | 0% | 0.05% | 0% | 0% | |

| Esophageal abscess | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0.04% | 0% | |

| Ulceration over prostheses | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0.40% | |

| Death | 0% | 0% | 0.05% | 0.04% | 0% | |

| Minor complications | • Sore throat(0.35%) | - | • Superficial mucosal injury | • Garlic odor for several hours(due to DMSO) | • Sore throat (15%) | |

| •Chest soreness(0.17%) | • Burn at pad site (0.02%) | • Chest pain (5%) | ||||

| • Abdominal pain(0.15%) | • Transient A. fib (0.02%) | • Nausea/ vomiting(0.8%) | ||||

| • Chest pain (82%) | ||||||

| • Bloating(0.02%) | • Bloating (0.02%) | • Erosive duodenitis(0.8%) | ||||

| • Transient dysphagia(13%) | ||||||

| • Gastroparesis and ulcerative esophagitis (0.02%) | • Retrosternal pain (0.4%) | |||||

| • Transient dysphagia (0.05%) | ||||||

| • Belching/ burping | • Poor sleep (0.4%) | |||||

| • Low grade fever | • Bloating/ flatulence | • Abdominal pain (0.4%) | ||||

| • Bronchospasm(0.01%) | • Transient dysphagia | • Fever | ||||

| • Transient chest pain | • Rash (0.4%) | |||||

| • Topical anesthesia-related complications(eg. Allergy, hypotension) | • Cough (0.4%) | |||||

Studies demonstrate that laparoscopic Nissen fundoplica-tion (LNF) is feasible and effective after failed ELGP[23,24]. Patients should undergo upper GI endoscopy before surgery but suture removal is not necessary. No significant scarring or adhesions have been noted in the esophageal hiatus or inferior mediastinum at LNF. This may be due to the stitches not penetrating beyond the muscularis propria, as penetration of the serosa has been shown to induce more scarring[21]. This in itself might contribute to the lack of durability in post-ELGP results. Although the technique is initially effective, long-term symptom control has yet to be established.

Alternatively, patients who experience recurrent GERD symptoms post-ELGP may benefit from a second procedure. However, one study demonstrates a significant trend toward earlier onset of recurrent symptoms after repeat ELGP[25].

Easy repeatability, short operative time, early discharge, no morbidity and symptomatic improvement make ELGP an attractive option. Endoscopic gastroplication has proven short term efficacy and has been demonstrated to be cost-effective for one to two years[26].

The absence of objective improvement after ELGP is disconcerting. No studies have shown improvement in LES pressure or length and grade of esophagitis. pH monitoring results are mixed but the rate of normalization is only 30%-40% between studies. Several studies have compared ELGP with LNF[27-29]. Comparable improvement in symptom scores, reduction in PPI intake and QOL assessments has been seen, however, surgery is superior to ELGP in patient satisfaction and objective improvement in reflux.

Recently, Chang et al showed that ELGP with cautery did not improve LESP, Gastric yield volumes, pressures or GEJ compliance in a porcine model, however, limited sample size (n = 5) precludes definitive analysis[30]. Lack of durability is another reason for concern as shown by many authors. Lepoutre et al reported loss of 51% plications in 60 patients at one year follow up[31].

The optimal configuration for plications is not known. In a small and unfortunately underpowered study by Davis et al 22 patients with proven GERD were randomized between a helical and circumferential plication pattern. No difference in outcome was observed between configurations at 18 mo although a trend in objective results favored the helical pattern[32]. At 18-mo follow up, only 15% of patients being asymptomatic and off antisecretory medication. The prevalence and persistence of these possible advantages are currently subject to investigation. Increasing the number of plications, when using the helical pattern, did not show a significant benefit at either 6- or 12- mo follow-up[32].

Current endoscopic suturing techniques usually involve submucosal suture placement, which may limit potential procedure-related complications but may also lead to early suture dehiscence and loss of long term efficacy. This problem may be theoretically solved by full thickness suturing or stapling devices, which include pledgets. Such an approach may, however, increase the risk of subsequent perforation. A novel technique of applying a full-thickness plication endoscopically has been developed and recently underwent clinical study in a U.S. multicenter trial. Selection criteria were similar to that shown in Figure 1.

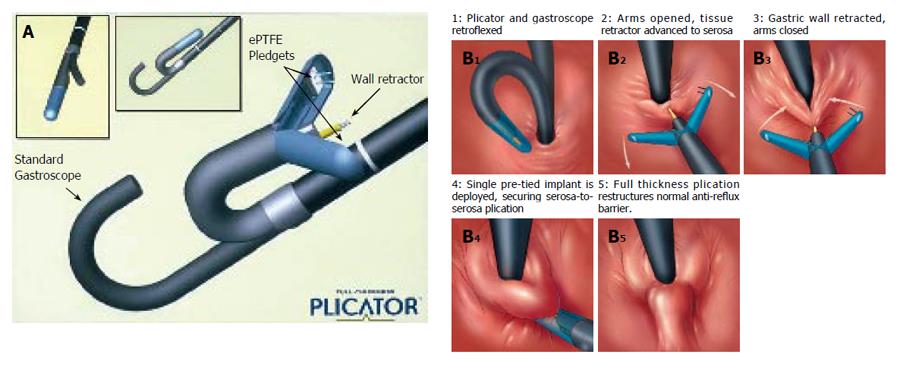

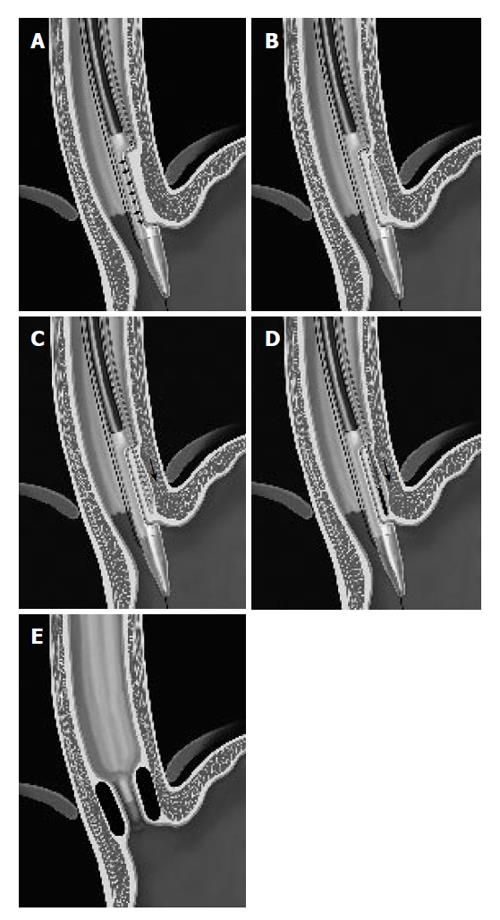

The (NDO) plicator (Figure 3A) is designed to apply a full thickness pledget reinforced U stitch tissue near the GE junction with serosa to serosa apposition. The system consists of a reusable instrument and a single-use suture-based implant. Additionally, a proprietary endoscopic tissue retractor and a 5 mm diameter endoscope are used to perform the procedure[33]. The tissue retractor is designed to engage the deep gastric wall, allowing for creation of the serosa to serosa plication.

With the patient under conscious sedation, a gastroscope is passed into the stomach for endoscopic inspection and passage of a guidewire. The gastroscope fitted with the plication device is passed into the stomach over the guidewire. The suture applicator is retroflexed and properly positioned under endoscopic vision. The endoscopic tissue retractor is then inserted to within 1 cm of the GE junction and advanced to the level of the serosa which is judged by visible tenting of the tissues around the entry point of the retractor. The gastric wall is then retracted and instrument arms are closed upon it. The pre-tied implant is deployed to secure a full-thickness plication. The tissue retractor is removed from the greater curvature side of the GEJ, the jaws opened and entire assembly is removed from the stomach followed by removal of the overtube (Figure 3B 1-5). The approximate procedural time is 15-20 min.

Pooled results for NDO plicator are shown in Table 1. A multi-center study enrolled 64 patients with symptomatic GERD who were dependent on antisecretory medication and showed evidence of esophageal acid exposure (pH-metry) without an underlying motility disorder. Follow up was completed at 1, 3 and 6 mo post-procedure. It showed a significant reduction in GERD symptom scores, medication usage and esophageal acid exposure on 24-h pH-study, which persisted at one year follow up. No significant changes in esophageal manometry were noted[34]. At 6-mo follow up, there was a 63% symptom score improvement with elimination of PPI therapy in 74% and normalization of pH in 30% patients. No patient required re-treatment during the 6-mo follow up. In this initial trial, one full thickness plication was used. A pilot study on 7 patients also showed similar results but failed to show objective improvement of reflux[35]. Further studies with single vs multiple plications are anticipated. No sham controlled trial has yet been completed but one is being organized.

This procedure aims at inducing fusion of the opposed gastric tissue and thereby reducing distensibility at the GEJ. Feitoza et al[21] showed maximal fibrosis with incorporation of serosa in the plication when compared to other depths of suture plication. Theoretically, the suture retention rate and thus, durability of results should also improve. Lengthening of the intra-abdominal segment of the LES[33] is expected.

The most common complication was sore throat (spon-taneously resolving within several days post-procedure). One gastric perforation did occur during the multi-center trial and was managed conservatively.

This is a promising new endoluminal suturing/com-pression implant device that has the capacity to place two titanium plications at once, thus, decreasing technical variability between operators (Figure 4). The distance between the two stitches is pre-determined. The plications are removable within the first 48 h. Withdrawal of the device is not necessary after each stitch which may decrease the procedure time and anesthesia related complications. Implantation is performed using a standard endoscope and no overtube is required. The mean procedure time is 21 min. Initial results show the device to be safe and time-efficient. An expanded multicenter pivotal phase I study is ongoing and will help clarify the procedure results.

The results of feasibility trials involving 8 patients with symptomatic GERD, abnormal pH scores, normal motility and responsiveness to daily PPI use have been published. Patients with large hiatal hernias (>2 cm), esophagitis (grade II or more) and Barretts esophagus were excluded. At 6 mo follow up, 75% were off PPI’s, 68% improved GERD-HRQL score and 40% improved GSRS:GERD score. However, 24-h pH and manometry showed no significant improvement. (S1199)

Serious complications have not been encountered. Minor adverse effects seen to date are sore throat, epigastric/referred chest pain and the gas bloat syndrome.

Radiofrequency energy (RFe) has been extensively utilized in medicine since 1921 and is currently being used in the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy, cardiac arrythmias and metastatic liver lesions. The possibility of RFe being used for GERD therapy was explored after successful treatment of snoring and sleep apnea.

Radiofrequency augmentation of the LES has been widely used. Over 3500 procedures have been performed in the United States alone. The indications in the past have been confined to patients with early reflux disease. The Stretta procedure may have specific utility in morbidly obese patients, those with a previous gastric resection, a gastric bypass, after a failed LNF[36] or as an alternative to re-operation after fundoplication disruption. In a porcine fundoplication disruption model, fluoroscopic guidance improved RF lesion accuracy therefore it has been suggested that fluoroscopic guidance be utilized to ensure probe placement[37]. Patients with failed anti-reflux surgery and subsequent RF therapy have experienced non-significant symptomatic improvement (heartburn score from 3.33 pre-procedure to 2.75 post-procedure), however, patient satisfaction scores are significantly improved[38]. The role of the Stretta procedure in postoperative fundoplication patients remains unclear.

The Stretta catheter (Figure 5A) is a flexible, handheld, disposable 20F Savary-style dilator that is used in con-junction with the Curon (Sunnyvale, California) control module. It is comprised of a balloon basket assembly, 4 nickel titanium electrodes, suction and irrigation. The balloon basket deploys 4 radially arranged electrodes into the smooth muscle of the GE junction. Tiny thermocouple temperature sensors within the electrodes provide temperature feedback to the radiofrequency generator. A target temperature is pre-selected and the power is automatically discontinued if the temperature exceeds the predetermined threshold. The needles also provide feedback on impedance which allows the operator to know if the needles are positioned correctly into the tissue.

Under conscious sedation, the catheter is placed over the guidewire into the stomach and withdrawn to the position of needle deployment. After removal of the guidewire, the balloon at the distal end of the catheter is inflated, the electrodes are deployed and RF is applied for a specific period of time while monitoring the temperature and impedance levels (Figure 5B). A first treatment ring of 8 lesions is created by rotating the catheter 45º and repeating the same. Four such antegrade rings, each with 8 lesions, are created at 0.5 cm intervals to a distance of 1cm below the GE junction. Two further gastric “pull-back” rings, of 12 lesions each (3 sets of deployment each), complete a set of thermal lesions (Figure 5C). Halfway through the procedure, an endoscope is reintroduced to verify the location of treatments with subsequent adjustment distally or proximally to prevent superimposition of lesions. Following recovery, patients continue their usual anti-reflux medication for 3 wk. A modified technique has been proposed in the presence of a large hiatal hernia (>3 cm) or a failed Nissen fundoplication[39]. The modified technique creates 6 anterograde treatment levels instead of 4, beginning 1 cm above the squamocolumnar junction with 5mm between levels and placing 2 sets of lesions at each of the 4 proximal levels and 3 sets at the distal 2 levels.

In the initial US open label trial[40], one year follow up showed a significant decrease in symptom scores. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease-specific quality of life satisfaction scores and distal acid exposure were significantly improved over the baseline on-medication scores as well. However, normalization of pH monitoring scores did not occur in the majority of patients. In addition, LES pressures did not increase and esophagitis did not improve significantly at 6 mo endoscopic follow-up.

The sham-controlled trial[41] showed significant improvement in symptom scores and quality of life at 6 and 12 mo, but at 6 mo there was no difference between groups in medication usage. Esophagitis grade did not show improvement, and in fact grade 2 esophagitis increased in severity in both groups. Similarly, pH scores also failed to show significant improvement, unlike the previous uncontrolled studies[40,42]. The explanation for these findings may be altered sensitivity of the distal esophagus or unusual persistence of the sham effect.

In a registry series[43], 558 patients underwent the Stretta procedure and showed a significant improvement in GERD symptom control (from 50% to 90%) and patient satisfaction (from 23% to 86% at a mean follow up of 8 mo. The onset of GERD relief was in less than 2 mo in most patients (69%). The treatment effect was durable beyond 1 year and most patients (51% at one year vs 96% pre-procedure) were off all antisecretory drugs at follow-up. Most studies are limited to short term follow up (up to 12 mo). For the first time, Torquati et al reported long term results in 41 patients with 83% being highly satisfied at a mean follow up of 27 mo[44]. Proton pump inhibitor usage was discontinued in 56% patients and was significantly reduced in 87%. Similarly, Reymunde et al demonstrated significant and sustained improvement in anti-secretory drug discontinuation (88%), GERD symptom scores (82%) and QOL scores (44%) at more than 3 years of follow-up[45]. This is encouraging evidence and suggests that durability of results is the distinguishing attribute for the Stretta procedure.

Significant improvement in symptom scores and quality of life have also been observed in shorter term studies[40,43,46,47]. Similarly, decreased PPI use and increased patient satisfaction have been consistently seen[46,40,47]. Most studies fail to demonstrate a beneficial effect of Stretta on esophagitis but Triadofilopoulos et al[42] showed an improvement in esophagitis grade, from 21% with grade 2 esophagitis to 9.3% post-procedure in 43 patients at 6 mo. The role of Stretta in improving extra-esophageal manifestations of GERD is still not clear, however, one study[36] suggests that respiratory benefit can be achieved if strict patient selection (abnormal pH study) is followed. Pooled results are shown in Table 1.

Multiple changes may be responsible for the effect seen in the Stretta procedure. First, a mechanical alteration and thickening of the LES musculature leads to diminished reflux, as shown in the canine model[48]. Secondly, progressive tissue remodeling and scar formation observed after Stretta could contribute to the decreased compliance and an increased tensile strength of the GE junction which also exerts its effect in decreasing tLESRs. This decrease in tLESRs has been shown in both animals and humans[48,49]. Histologically normal muscle with occasional focal areas of collagen deposition at 8 wk follow up has been shown in the porcine model.

The disparity between symptomatic improvement and acid exposure seen in the sham trial was surprising and might be explained by a residual sham effect on symptoms or altered visceral sensitivity[41]. The later would explain the striking dichotomy between symptom relief and minimal to moderate improvement in acid reflux profiles. A diminished sensitivity may be due to destruction of chemosensitive or mechanosensitive nerve endings[50]. However, some studies contradict this contention[44] by showing significant improvement in pH results at 27 mo in patients who had responded to therapy.

The major and minor complications are shown in Table 2. The 5 perforations and 2 deaths occurred during the learning curve and were due to poor patient selection and technical errors. No major complications were seen in the multi-center trial and subsequent studies have not shown adverse effects on vagal nerve function or gastric emptying. The complication rate after Stretta has been < 0.6% since the introduction of the new technology and 0.13% in the last 12 mo.

Operators should check the position if abnormal impedance/temperatures are observed, use correct balloon pressures, control the mucosal temperature carefully, minimize balloon pull back pressure and avoid NG tube placement for one month post-procedure

In the US open label trial, 5% of the patients elected to undergo fundoplication 6-12 mo after Stretta due to incomplete or recurrent symptom response. In each case, there was no evidence of extra-esophageal tissue abnormality and the anti-reflux operation was performed in a normal manner and without difficulty. Richards et al[36] compared the outcome of patients who had the Stretta procedure and a laparoscopic fundoplication at 6 mo and found a comparable and significant improvement in QOLRAD, SF-12 and pH scores in both groups. However, medication usage was significantly less in patients who had surgery (97% vs 58% off PPI’s). Both groups were highly satisfied with their procedure. A repeat Stretta procedure is not recommended.

Enteryx consists of a biocompatible polymer (80 g/L EVOH with a radioopaque contrast agent dissolved in an organic liquid carrier [DMSO]). Upon contact with tissues or body fluids after injection, the solvent, DMSO, rapidly diffuses resulting in precipitation of the polymer (EVOH) as a spongy mass. It is not biodegradable and has no antigenic properties. Migration through blood vessels or lymphatics nor prosthetic contraction after injection have been observed[51].

The three components of Enteryx, ethylene vinyl alcohol polymer (EVOH), dimethyl sulfoxide DMSO, and tantalum, have been previously used together medically as a vascular embolization agent and a membrane for hemodialysis and plasmapheresis.

Enteryx is a treatment with promise but, like other endoluminal therapies, is lacking objective supportive data. Patients must understand that the procedure is irreversible[52]. The possible future indications for En-teryx include primary therapy for GERD in patients who respond to PPI’s but prefer not to take medications daily, salvage therapy for PPI responders to reduce or eliminate daily medications and salvage therapy for surgical failures[52]. Recently, Enteryx has been attempted in pos-fundoplication patients[53].

Enteryx therapy is clearly contraindicated in any individual who does not have physiologically documented GERD by pH study or endoscopic findings. It is also contraindicated in individuals who cannot undergo or tolerate endoscopy and those who have esophageal varices. There is no reported experience with this procedure in individuals with esophageal motility disorders, prior gastric or GERD surgery, scleroderma, Barrett’s esophagus, hiatal hernias >3cm, BMI >35 or patients who use anticoagulants other than aspirin[52].

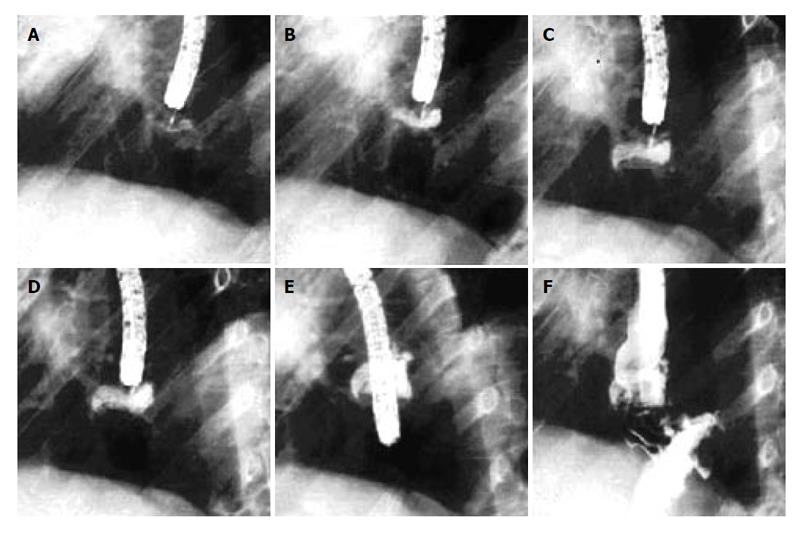

The procedure is performed in an endoscopy suite equipped with fluoroscopy under conscious sedation. A long needle catheter is filled with Enteryx after it has been flushed with DMSO, to keep it liquefied as long as it stays within the catheter. The prepared injection needle is placed into the muscularis propria at the appropriate level of the esophageal wall. The prosthesis is injected at a rate no greater than 1mL/s under combined fluoroscopic and endoscopic guidance (Figure 6). The EVOH solidifies within the esophageal wall as the generated heat causes DMSO to dissipate. The injection is stopped if either a submucosal or transmural injection is observed. Submucosal accumulation of material is seen endoscopically as a black bulge and an extramural injection is demonstrated on fluoroscopy as either flow of material beyond the muscularis into the mediastinum or the abdominal cavity, or lack of a visible deposit in the esophageal wall. If a circumlinear transverse path of material is visualized under florosocopy, the injection is completed at this stie using a total of 1 to 2 mL. The procedure is considered satisfactory if 6 to 8 mL of Enteryx is delivered to the muscularis propria circumferentially without a submucosal or transmural injection. After the injection is complete at one site, the needle remains in place for 20 s allowing the material to stabilize and solidify. This maneuver prevents leakage of the prosthesis into the esophageal lumen. Patients are usually discharged 2 to 4 h after recovery.

Robert et al reported Enteryx implantation in 5 pigs without the use of fluoroscopy. Enteryx was consistently deposited into the deep esophageal wall with a high degree of accuracy in a minimal amount of time. The placement was accurate in 85% and was transmural in just one instance. A human trial is underway to confirm these findings[54].

Enteryx implantation significantly improves the QOL scores and medication usage[51,52]. No change has been seen in the severity of esophagitis at endoscopy after Enteryx implantation. In general, the structural characteristics of the LES, including its length and pressure, are not altered significantly. Pooled results are shown in Table 1.

The 2 year follow up results of this U.S multicenter trial, which included 85 patients, were recently published[55] and showed PPI use to be eliminated in 74% of patients at 6 mo follow up. This effect was maintained in 64% of subjects at 2 years while 74% were maintained on less than half of their baseline PPI dosage. The improvement in symptom scores was 82% at 6 mo and 70% at 2-yr. Quality of life (SF-36) questionnaires demonstrated an improvement of 6% from baseline at 3 mo and 3% at 12 mo for the mental score while the improvement in the physical score was maintained at 12% at both 6 and 12 mo follow up. pH scores improved with 30% normalization and there was a small but significant LES length augmentation (1 cm) following therapy[56]. No significant change in LES pressure was observed. The absence of change in LES resting pressure contrasts with findings from the pilot study, in which a significant increase in the LES pressure was observed at 6 mo. This may have been due to the inclusion of patients with a normal LES pressure at baseline or the smaller sample size in the pilot study. Importantly, most of the decline in treatment responders during follow-up occurred between 1 and 6 mo. Between 6 and 12 mo, the proportion of treatment responders remained stable. There was no evidence that the reduction in PPI usage after the implant procedure was due to medication shifting.

The decline in residual implant volume seen after one month was attributable to sloughing of superficially implanted material until encapsulation was complete. There was no radiographic evidence of implant migration and after 3 mo, residual volume remained stable (P > 0.1)[57]. Twenty two percent of patients were re-treated at 3 mo follow up of which, 63% improved at 12 mo follow up with 58% completely off PPI’s and 5% of patients reducing their PPI usage by more than 50% of baseline[56].

The multicenter randomized controlled sham trials with “cross-over” option starting at 3 mo post-randomization are currently underway in both Europe and the United States[58]. An interim report on 56 out of the 64 total European patients has been announced with 3 mo follow up. An improvement in GERD HQRL was seen in 65% patients in the Enteryx arm vs 21% in the sham arm. The median change in symptom scores was 15 for the Enteryx group and 4 for the sham group. There was also a greater reduction in PPI usage (64% vs 33%) and a lower cross-over/re-treatment incidence (21% vs 71%) in the Enteryx group when compared to the sham group. Criteria for both cross over (for controls) and re-treatment (for the Enteryx group) were the same i.e. an off-PPI HQRL score > 15[58].

Johnson et al reported that the likelihood of a successful clinical outcome is higher with more residual implant volume. He showed that all patients who retained ≥ 5 mL of implant material eliminated or reduced PPI use by ≥50% and the majority of subjects who retained > 5 mL of Enteryx achieved a GERD-HRQL score of < 15. Lehman et al reported the procedure to be equally effective irrespective of the radiologic pattern evident at the time of implantation[59]. In a study evaluating predictors of outcome for Enteryx, Deviere et al[60] showed there was no statistically significant difference in PPI usage or pH outcome by gender, but GERD-HRQL symptom scores were significantly more likely to improve in males (86%; 57/66) than in females (67%; 32/48) (P = 0.01). Finally, Ganz et al compared the endoscopic findings of patients from the multicenter study at 1 yr follow up with their baseline values (on PPI’s) and reported that treatment with Enteryx provided improvement in esophagitis scores comparable to that provided by PPI medication[61]. This finding, however, has not been supported by other studies. A pilot study determining the efficacy of Enteryx in post-fundoplication patients (n = 19) and reported no apparent difficulty due to the distorted anatomy during the procedure. Post-fundoplication patients with refractory symptoms on high dose PPI therapy were enrolled and ‘improvement’ was seen in 89% of patients, however, this study primarily addressed the technical feasibility rather than the efficacy of post-fundoplication Enteryx implantation[53].

Both gross and histological examination in animals have shown that the implants persist as encapsulated, firm, smooth, slightly mobile ovoid masses, several weeks after implantation. No evidence of pathologic inflammatory changes in the surrounding tissues have been observed. However, the implants lead to a significant increase in the yield pressure and yield volume with a raised threshold for transient relaxations after implantation[6].

Fibrous encapsulation may functionally lengthen the LES. The encapsulation/scarring is the probable mechanism of effect but the exact mechanism in humans remains to be fully characterized. The “bulking” effect, seen with some injectable treatments for urinary incontinence, is not apparent for Enteryx because follow-up endoscopies reveal no evidence of luminal narrowing. Sloughing of superficially injected material may be the reason for inadequate clinical outcome and lack of durability seen in some patients[57].

The complications are shown in Table 2. Recently, one death was reported in a patient due to inadvertent injection of Enteryx into the aorta. Further details are not yet available. Two patients experienced a pericardial effusion after injection of the prosthesis and subsequently underwent a pericardial window. Two additional patients developed a pleural effusion but no other problems were recognized. Although, the cause of the effusions is not clear, extension of an inflammatory process from the esophagus to the surrounding structures namely pericardium and pleura and the possibility of an allergic or infectious process cannot be ruled out.

All operators are required to receive hands on laboratory training prior to clinical utilization. Injection techniques when using fluoroscopy are emphasized and guidelines for prostheses preparation are given. Most centers place patients on a liquid diet followed by a soft diet, the day of the procedure followed by normal diet the day after. Maintenance therapy with PPI’s is continued for 10-14 d after implantation.

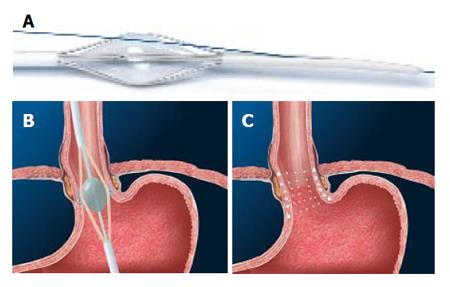

Gatekeeper is a dehydrated hydrogel prosthesis implanted into the submucosa of the cardia/LES. It hydrates to 6 mm × 15 mm cylinder shaped soft pliable cushions and is removable by endoscopy[62].

In addition to the general selection criteria already described, patients with esophageal varices, a peptic stricture and morbid obesity were excluded from the trials for Gatekeeper.

The Gatekeeper device consists of an overtube with separate channels for passage of an endoscope and a long delivery sheath (Figure 7). After placement of the overtube, the injection capsule is placed through the overtube to straddle the squamocolumnar junction. A vacuum is created to stabilize the device and to draw the mucosa in. The injection needle is advanced into the submucosa followed by injection of 3-6 mL of sterile saline until blanching is observed. This is followed by removal of the injection needle and advancement of the needle assembly and the delivery sheath into the mucosa, leaving the delivery sheath in the submucosal plane. After the needle assembly has been retracted, the prosthesis is inserted into the proximal end of the delivery sheath and advanced to the submucosal level using a pushrod assembly. Up to 6 hydrogel implants are placed. The implants are small and “sliver”-like when introduced but swell to full size within 24 h, when hydrated.

In a limited number of patients the Gatekeeper procedure has been shown to significantly decrease heartburn, improve quality of life, 24-h pH-metry scores and decrease medication usage[63]. The success rate for implantation is 93% while the procedural success rate was reported at 98.7%[64]. Pooled results for Gatekeeper are shown in Table 1.

After completion of a 6 mo pilot study[65] with favorable results, a European multicenter study was initiated[66]. Patients underwent manometry, endoscopy, 24-hr pH-metry and symptom scoring before and after the procedure. The average number of prostheses implanted was 4.3 (2-6). Final results showed significant improvement in symptom scores (HRQL score from 24 to 5), quality of life, pH parameters (% time pH < 4, 9.1% to 6.1%) and LESP (8.8 to 13.8 mmHg) at 6 mo[64]. The prosthesis retention was 70% at 6 mo. Other studies with smaller numbers of patients have failed to show significant improvement in LESP, however, symptom scores and pH results show consistent improvement[63,66].

An international, prospective multi-center (US/European) randomized, sham-controlled Gatekeeper trial has recently commenced[67]. One hundred and forty four patients with symptomatic GERD dependent on PPI with evidence of reflux on 24-h pH study and a symptom score of > 20 off medications are being included in the study. Patients with Barretts esophagus, hiatal hernia > 3 cm, esophagitis (garde II or higher), stricture formation, varices or prior antireflux surgery will be excluded. Randomization will be attempted with a sealed envelope at a rate of 2:1 implant vs sham. Four implants will be placed circumferentially in the distal LES/cardia with re-treatment offered to individuals if GERD symptoms persist. Sham patients will be offered Gatekeeper therapy at 6 mo. Patients will take anti-secretory medications on a PRN basis. Outcome parameters are HRQL, esophagitis, medication use, 24 hr pH monitoring and implant persistence. To date, 52 subjects have been enrolled and randomized, 21 of whom have been implanted. Enrollment completion is anticipated in April, 2005[68].

The mechanism of action is probably similar to Enteryx in addition to bulking. The prosthesis narrows the lumen as seen at 6 mo follow-up endoscopy and is self contained.

The complications reported at 6 mo follow-up are shown in Table 2[64]. In the largest multicenter study, 2 out of 40 patients (5%) developed severe complications which included esophageal perforation caused by overtube placement and severe postprandial nausea (1 wk post-procedure) leading to endoscopic removal of the prosthesis at 3 wk[64].

The Gatekeeper prosthesis is removable by endoscopic means. A needle knife can be used to incise over the edge of the implant which is then suctioned from its submucosal pocket[62]. Endoscopic ultrasound may be used for exact localization of the prosthesis. Of note, one of the two patients who had the prostheses removed was 7 mo post-procedure. All 3 prostheses were removed in the other patient, 3 wk post-procedure. No complication was encountered with either patient.

A trial of gelatinous plexiglass (polymethylmethacrylate, PMMA) microsphere implants has been published by Feretis et al[69]. A mean volume of 32 mL was implanted submucosally, 1-2 cm proximal to the squamocolumnar junction, in 10 patients with a 21-gauge needle. Transient dysphagia was noted in one patient due to excessive implant volume. At a mean follow-up of 7.2 mo, there was significant improvement of GERD-related symptoms and 24-h pH-studies (decreased from 24.5 to 7.2) but pH normalization was not seen. Ninety percent of patients were completely off PPI’s at 6 mo follow-up. The procedure was found to be safe at short term follow-up.

Minor and self-limited complications occurred in 4 of 10 patients (40%). Transient dysphagia and the gas-bloat syndrome (10%) were thought to be due to excessive treatment with an implantation volume of 39 mL. The plexiglass injection was not associated with local or systemic complications and is not antigenic. Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) is highly viscous and therefore a sigmoidoscope with a larger biopsy channel that accommodates a large caliber catheter was used for implantation. Longer follow-up studies are needed[69]. A multicenter study is currently being planned.

In addition, to these bulk-forming implants, injection therapy with sclerosing agents which induce focal necrosis and fibrosis similar have been tried. Sodium Morrhuate was used in 15 refractory GERD patients but after a year of follow up, the authors concluded that the therapy was ineffective[70].

The use of endoscopic therapies after a failed fun-doplication has been seen with ELGP, Stretta and Enteryx and their preliminary results have been discussed above. A combination of two different endoscopic therapies may be a solution to the lack of durability and objective benefit seen with these procedures. Anderson reported results of a pilot study done on 5 patients who were symptomatic and had radiological or pH probe evidence of reflux after prior ELGP procedure. These patients underwent Enteryx implantation and 3 of the 5 patients were off medication (60%) at a mean follow up of 7.6 mo. Transient dysphagia was seen after implantation in two patients but no major adverse effects were observed. Larger studies with longer follow up and objective documentation of improvement will help elucidate the efficacy of the combination approach[71].

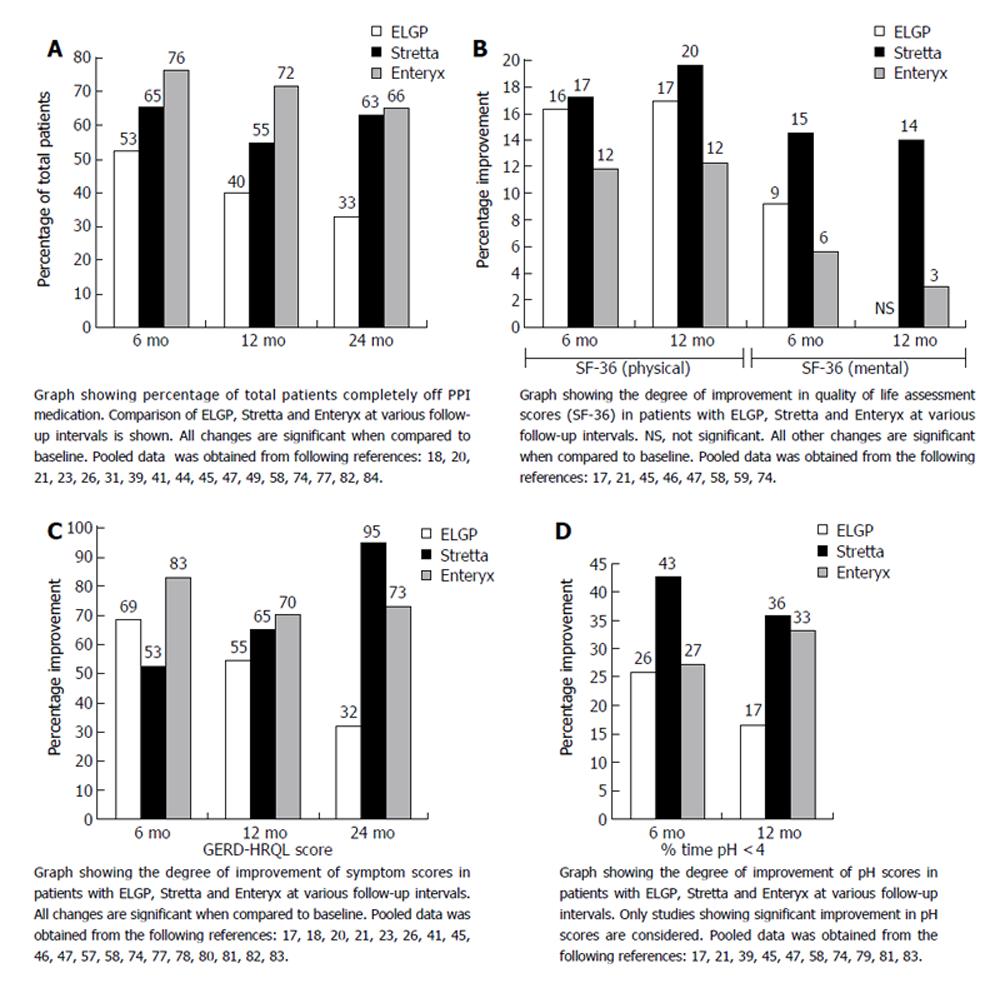

The endpoints studied in most of the trials are GERD symptoms scores (HRQL), medication usage, manometric findings, grade of esophagitis and 24 hr pH-study results. In general, the procedures are safe with 3 deaths in 9000-10 000 cases. At present, the overall complication rate reported for ELGP, Stretta, Enteryx and Gatekeeper is 11%, 6%, 6.7% and 15% respectively[64]. All studies, to date, allow use of PPI’s and most gauge success by the number of patients decreasing PPI dosage and symptomatic improvement. Meaningful conclusions cannot be made in this instance. There is evidence of symptomatic relief with decreased medication usage but with failure of an increase in LES length and pressure, healing of esophagitis and improvement in pH scores. An overview of the procedure for different endotherapies for GERD is shown in Table 2. A comparison of results in patients with Endocinch, Stretta and Enteryx at various follow-up intervals is also depicted in graphic format (Figures 8A-D).

In conclusion the scientific community needs to wait for industry-independent trials showing endoscopic and 24 hour pH monitoring follow-up data that establishes long term efficacy and prolonged symptomatic benefit. Cost-effectiveness and post-marketing documentation of complications will better define the “true” role of these procedures in the management of GERD patients.

| 1. | Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1488] [Cited by in RCA: 1384] [Article Influence: 47.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liebermann-Meffert D, Allgöwer M, Schmid P, Blum AL. Muscular equivalent of the lower esophageal sphincter. Gastroenterology. 1979;76:31-38. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Massey BT. Potential control of gastroesophageal reflux by local modulation of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations. Am J Med. 2001;111 Suppl 8A:186S-189S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hirsch DP, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Dagli U, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. Effect of prolonged gastric distention on lower esophageal sphincter function and gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1696-1704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kahrilas PJ. GERD pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70 Suppl 5:S4-S19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mason RJ, Hughes M, Lehman GA, Chiao G, Deviere J, Silverman DE, DeMeester TR, Peters JH. Endoscopic augmentation of the cardia with a biocompatible injectable polymer (Enteryx) in a porcine model. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:386-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Lieberman DA. Medical therapy for chronic reflux esophagitis. Long-term follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1717-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | DeMeester TR, Peters JH, Bremner CG, Chandrasoma P. Biology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: pathophysiology relating to medical and surgical treatment. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:469-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Spechler SJ, Lee E, Ahnen D, Goyal RK, Hirano I, Ramirez F, Raufman JP, Sampliner R, Schnell T, Sontag S. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2331-2338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 660] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kadirkamanathan SS, Evans DF, Gong F, Yazaki E, Scott M, Swain CP. Antireflux operations at flexible endoscopy using endoluminal stitching techniques: an experimental study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:133-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Horatogis A, Hieston K, Lehman G. Evaluation of supplemental cautery during endoluminal gastroplication for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. AB. DDW. 2003;. |

| 12. | Filipi CJ, Lehman GA, Rothstein RI, Raijman I, Stiegmann GV, Waring JP, Hunter JG, Gostout CJ, Edmundowicz SA, Dunne DP. Transoral, flexible endoscopic suturing for treatment of GERD: a multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:416-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen YK, Raijman I, Ben-Menachem T, Starpoli AA, Liu J, Pazwash H, Weiland S, Shahrier M, Fortajada E, Saltzman JR. Long-term outcomes of endoluminal gastroplication: a U.S. multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:659-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rothstein RI, Hynes ML, Grove MR, Pohl H. Endoscopic gastric plication for GERD: A randomized, sham-controlled, blinded, single-center study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:AB111. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Mahmood Z, McMahon BP, Arfin Q, Byrne PJ, Reynolds JV, Murphy EM, Weir DG. Endocinch therapy for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a one year prospective follow up. Gut. 2003;52:34-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tam WC, Holloway RH, Dent J, Rigda R, Schoeman MN. Impact of endoscopic suturing of the gastroesophageal junction on lower esophageal sphincter function and gastroesophageal reflux in patients with reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:195-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Martinez-Serna T, Davis RE, Mason R, Perdikis G, Filipi CJ, Lehman G, Nigro J, Watson P. Endoscopic valvuloplasty for GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:663-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu JL, Knapp R, Silk J, Carr-Locke DL; Treatment of medication refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease with endoluminal gastroplication. Gastrointest Endosc 55; AB257. . |

| 19. | Hong D, Swanstrom L. Endoscopic plication as salvage procedure for failed surgical fundoplications in select patients. AB Surg Endosc Supp. 2004; S222. |

| 20. | Pazwash H, Gualtieri NM, Starpoli A. Failed surgical fundoplication: A possible new indication for endoluminal gastroplication. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S212, AB 646. |

| 21. | Feitoza AB, Gostout CJ, Rajan E, Smoot RL, Burgart LJ, Schleck C, Zinsmeister AR. Understanding endoluminal gastroplications: a histopathologic analysis of intraluminal suture plications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:868-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu JJ, Glickman JN, Carr-Locke DL, Brooks DC, Saltzman JR. Gastroesophageal junction smooth muscle remodeling after endoluminal gastroplication. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1895-1901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Velanovich V, Ben Menachem T. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication after failed endoscopic gastroplication. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2002;12:305-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tierney B, Iqbal A, Filipi C, Haider M. Effects of prior endoluminal gastroplication on subsequent laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:321-323. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Ben-Menachem T, Chen Y, Raijman I, Starpoli A, Pazwash H, Liu J, Carr-Locke D. Symptom recurrence after endoluminal gastroplication for GERD: Comparison of initial versus repeat ELGP. AB. Gastointest Endosc. 2003;57:AB130. |

| 26. | Wiersema MJ, Levy MJ. Cost analysis of endoscopic antireflux procedures: endoluminal plication vs. radiofrequency coagulation vs. treatment with a proton pump inhibitor. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:749-750; author reply 750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mahmood Z, Byrne PJ, McCullouch J, Arfin Q, McMAhon B, Murphy E, Reynolds JV, Weir DG. A comparison of Bard Endocinch transoesophageal endoscopic plication (BETEP) with laproscopic nissen fundoplication (LNF) for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD). Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:AB463. |

| 28. | Chadalavada R, Lin E, Swafford V, Sedghi S, Smith CD. Comparative results of endoluminal gastroplasty and laparoscopic antireflux surgery for the treatment of GERD. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:261-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Velanovich V, Ben-Menachem T, Goel S. Case-control comparison of endoscopic gastroplication with laparoscopic fundoplication in the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: early symptomatic outcomes. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12:219-223. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chang KJ, Nguyen NT, Pandolfino JE, Nguyen PT. Endoluminal plication with mucosal ablation of the Gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) does not improve LES pressure, gastric yield pressure or GEJ compliance: Is it time to give up. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:AB129 [S1149]. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Lepoutre E, Boyer J, Grimaud JC, Letard JC, Escourrou J, Prat F, Ducrotte P, Canard JM, Rey JF, Ponchon T. Endoscopic suturing for GERD: Results at one year precludes the use of routine practice. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:AB136 [S1178]. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Davis Filipi CJ, Gerhardt J. Comparison of endoluminal gastroplication configuration techniques. AB. AJG. 2002;97:S30. |

| 33. | Pleskow D, Rothstein R, Lo S, Hawes R, Kozarek R, Haber G, Gostout C, Lembo A. Endoscopic full-thickness plication for the treatment of GERD: a multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:163-171. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pleskow D, Rothstein R, Lo S, Hawes R, Kozarek R, Haber G, Gostout C, Lembo A. Endoscopic full-thickness plication for the treatment of GERD: 12-month follow-up for the North American open-label trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Chuttani R, Sud R, Sachdev G, Puri R, Kozarek R, Haber G, Pleskow D, Zaman M, Lembo A. A novel endoscopic full-thickness plicator for the treatment of GERD: A pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:770-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Richards WO, Houston HL, Torquati A, Khaitan L, Holzman MD, Sharp KW. Paradigm shift in the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg. 2003;237:638-647; discussion 648-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Mcclusky D, Khaitan L, Gonzalez R. A comparison be-tween standard technique and fluoroscopically guided radiofrequency energy delivery in the treatment of fundoplication disruption. AB. SAGES. 2004;85. |

| 38. | Go MR, Dundon JM, Karlowicz DJ, Domingo CB, Muscarella P, Melvin WS. Delivery of radiofrequency energy to the lower esophageal sphincter improves symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Surgery. 2004;136:786-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Noar M, Knight S, Bidlack D, Towson . A modified technique for endoluminal delivery of radiofrequency energy for the treatment of GERD in patients with failed fundoplication or large hiatal hernia. AB. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:AB258. |

| 40. | Triadafilopoulos G, DiBaise JK, Nostrant TT, Stollman NH, Anderson PK, Wolfe MM, Rothstein RI, Wo JM, Corley DA, Patti MG. The Stretta procedure for the treatment of GERD: 6 and 12 month follow-up of the U.S. open label trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:149-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Corley DA, Katz P, Wo JM, Stefan A, Patti M, Rothstein R, Edmundowicz S, Kline M, Mason R, Wolfe MM. Improvement of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms after radiofrequency energy: a randomized, sham-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:668-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Triadafilopoulos G, Dibaise JK, Nostrant TT, Stollman NH, Anderson PK, Edmundowicz SA, Castell DO, Kim MS, Rabine JC, Utley DS. Radiofrequency energy delivery to the gastroesophageal junction for the treatment of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:407-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Wolfsen HC, Richards WO. The Stretta procedure for the treatment of GERD: a registry of 558 patients. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2002;12:395-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Torquati A, Houston HL, Kaiser J, Holzman MD, Richards WO. Long-term follow-up study of the Stretta procedure for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1475-1479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Reymunde A, Santiage N. The Stretta procedure is effective at 3+ year follow-up for improving GERD symptoms and eliminating the requirement for anti-secretory drugs. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:S29. |

| 46. | DiBaise JK, Brand RE, Quigley EM. Endoluminal delivery of radiofrequency energy to the gastroesophageal junction in uncomplicated GERD: efficacy and potential mechanism of action. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:833-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Houston H, Khaitan L, Holzman M, Richards WO. First year experience of patients undergoing the Stretta procedure. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:401-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kim MS, Holloway RH, Dent J, Utley DS. Radiofrequency energy delivery to the gastric cardia inhibits triggering of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and gastroesophageal reflux in dogs. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:17-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Tam WC, Schoeman MN, Zhang Q, Dent J, Rigda R, Utley D, Holloway RH. Delivery of radiofrequency energy to the lower oesophageal sphincter and gastric cardia inhibits transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations and gastro-oesophageal reflux in patients with reflux disease. Gut. 2003;52:479-485. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Kahrilas PJ. Radiofrequency therapy of the lower esophageal sphincter for treatment of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:723-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Devière J, Pastorelli A, Louis H, de Maertelaer V, Lehman G, Cicala M, Le Moine O, Silverman D, Costamagna G. Endoscopic implantation of a biopolymer in the lower esophageal sphincter for gastroesophageal reflux: a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Edmundowicz SA. Injection therapy of the lower esophageal sphincter for the treatment of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:545-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Yimcharoen P, Blosser AR, Brown MD, Ganz RA, Okolo P, Pleskow D, Raijman I, Lehman GA. Efficacy of Enteryx in post fundoplication patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:AB135 [S1176]. |

| 54. | Ganz RA, Rydell M, Termin P. Accurate Localization of Enteryx into the Deep Esophageal Wall Without Fluoroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:AB242. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 55. | Cohen LB, Johnson DA, Ganz R, Aisenberg J, Deviere J, Foley TR, Haber GB, Peters JH, Lehman GA; Enteryx solution, a minimally invasive injectable treatment for GERD: preliminary 24-month results of a multicenter trial. American College of Gastroenterology 68th Annual Scientific Meeting [AB]. . |

| 56. | Johnson DA, Ganz R, Aisenberg J, Cohen LB, Deviere J, Foley TR, Haber GB, Peters JH, Lehman GA. Endoscopic, deep mural implantation of Enteryx for the treatment of GERD: 6-month follow-up of a multicenter trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:250-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Johnson DA, Ganz R, Aisenberg J, Cohen LB, Deviere J, Foley TR, Haber GB, Peters JH, Lehman GA. Endoscopic implantation of enteryx for treatment of GERD: 12-month results of a prospective, multicenter trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Deviere J, Costamagna G, Neuhaus H, Voderholzer W, Louis H, Tringali A, Schumacher B. Endoscopic implantation of Enteryx for the treatment of GERD: A Randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:S296. |

| 59. | Lehman A, Hieston K, Cohen LB, D’Souza C, Aisenberg J, Ganz R, Walters J, Foley R, Porter M, Wagner K. Correlation Between Clinical Outcome and Enteryx Implant Shape. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:AB149. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 60. | Deviere J, Cohen LB, Aisenberg J, Ganz RA, Lehman GA, Foley TR, Johnson DA, Haber GA, Peters JH. Predictors of Enteryx Outcomes at 12 Months. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:AB243. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 61. | Ganz R, Aisenberg J, Cohen L, Neuhaus H, Schumacher B, Preiss C, Allgaier P, Fuchs KH, Hagenmuller F, Hochberger J. Enteryx solution, a minimally invasive injectable treatment for GERD: Analysis of endoscopy findings at 12 months. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:AB128. |

| 62. | Fockens P, Bruno M, Boeckxstaens G, Tygat GN. Endoscopic removal of the Gatekeeper system prosthesis. Gastrointes. Endosc. 2002;55:AB260. |

| 63. | Fockens P, Bruno M, Hirsch D, Lei A, Boeckxstaens G, Tygat GN. Endoscopic augmentation of the lower esophageal sphincter. Pilot study of the Gatekeeper reflux repair system in patients with GERD. Gastrointes Endosc. 2002;55:AB257. |

| 64. | Fockens P, Boeckxstaens G, Gabbrielli A, Costamagna G, Hattlebakk J, Odegaard S, Allescher HD, Roesch T, Muehldorffer S, Bastid J. Endoscopic Augmentation of the Lower Esophageal Sphincter for GERD: Final Results of a European Multicenter Study of the Gatekeeper System. Gastointest Endosc. 2003;59:AB242. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Fockens P. Gatekeeper Reflux Repair System: technique, pre-clinical, and clinical experience. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2003;13:179-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Fockens P, Costamagna G, Gabrielli A, Odegaard S, Hattlebakk J, Rhodes M, Allescher HD, Roesch T. Endoscopic augmentation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) for the treatment of GERD: multicenter study of the gatekeeper reflux repair system. [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:AB89. |

| 67. | Lehman G, Watkins JL, Hieston K, Johnson G, Yurek MT, Fockens P, Nickl NJ, Park A, Smith CD, Binmoeller K. Endoscopic Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) therapy with Gatekeeper System. Initiation of a multicenter prospective randomized trial (AB). Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:W1597. |

| 68. | Fockens P, Lei A, Edwomundowicz S, Lehmkuhl M, Cohen L, D’souza C, Rothstein R, Moriarty C, Nickl N, Nicholson S. Gatekeeper therapy: An endoscopic treatment for GERD: Randomized, sham-controlled multi-center trial overview. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:AB136 [S1177]. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 69. | Feretis C, Benakis P, Dimopoulos C, Dailianas A, Filalithis P, Stamou KM, Manouras A, Apostolidis N. Endoscopic implantation of Plexiglas (PMMA) microspheres for the treatment of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:423-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Schlesinger PK, Donahue PE, Sluss K. Endoscopic sclerosis of gastric cardia (ESGC) in severe reflux esophagitis: A human trial (AB). Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:33. |

| 71. | Anderson RD. Enteryx for relapsing GERD after previous endocinch treatment: Preliminary results fro five patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:AB126 [S1140]. [DOI] [Full Text] |

S- Editor Pan BR E- Editor Liu WF