INTRODUCTION

Intestinal enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma (EATCL) is highly aggressive, pleomorphic peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTL), usually with cytotoxic immunological phenotypes (TdT-, CD3+, CD5-, CD7+, CD4-, CD8±, CD45RO+, CD103+, HLA-DR-)[1-3]. This type of PTL originates from intraepithelial T-lymphocytes of small intestine mucosa and is associated with celiac disease (CD) in about 50% of the time[4,5]. Intestinal lymphoma develops in 7%-12% of CD cases[6]. It may even occur without any previous CD[6]. Infiltration of the kidneys is commonly found in disseminated lymphoma but rarely in primary renal lymphoma[7]. Acute renal failure (ARF) arising from bilateral renal infiltration is also uncommon[8,9]. Primary renal failure may occur and is usually of B-cell lineage[7]. It is rare for patients with lymphoma to develop ARF as their initial clinical presentation. The first report in which the phenotype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was established using renal biopsy was published by Miyake et al[10]. Renal lymphoma is commonly secondary due to lymphomatous infiltration of the kidneys in disseminated lymphoma and advanced stage IV of the disease. Different pathophysiological aggressive types of B-cell lymphoma such as Burkitt[11], precursor B-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia[12], mantle cell lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma[13] as well as PTL[14,15], T-cell rich B-cell lymphoma[8], make parenchymal neoplastic invasion of the kidneys. We present, as far as we know for the first time, ARF as the initial manifestation of EATCL.

Nevertheless, the intestinal lymphomas account for 20%-35% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL) of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and serological screening for CD is not recommended generally in people with lymphoma[16]. In patients with primary small intestinal disease, 9% are found to have small intestinal lymphoma[17]. Lymphomas involving the small intestine represent a heterogenous group with diverse pathogenic mechanisms[18] and high-risk MALT lymphoma is most frequently considered for differential diagnosis. EATCL, a type of PTL is most commonly localized in jejunum (70% of cases) but rarely in the colon and stomach. Gross examination can reveal multiple ulcers of jejunal mucosa frequently associated with perforation of intestinal wall or solitary lymph nodes[19]. Microscopy can show solitary epithelial lesions in the form of microabscess or lymphoepithelial lesions. In the adjacent mucosa, alterations are seen in CD such as crypt elongation, flattened mucosa and villi which are shortened, blunted or missing[2]. Tumor cells of the respective immunological phenotype have genetic characteristics as clonally rearranged TCR β and γ[5,6] can be arrested in varying stages of activation[1].

CASE REPORT

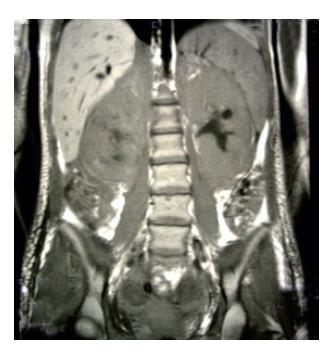

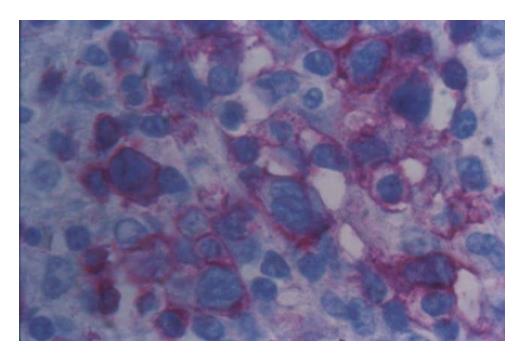

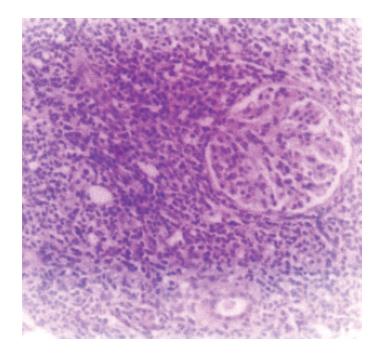

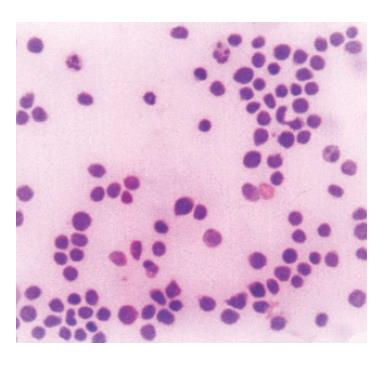

We report a case of female patient who was 23 years old with CD diagnosed at her age of 3 and had regular gluten-free diet regime. In March 1999, she was admitted to the Institute of Nephrology due to anemia and ARF. Clinical examination revealed excessive pallor of the skin and apparent mucous membranes with fever, splenomegaly +1 cm and ascites. A history was negative for exposure to nephrotoxins and hereditary renal diseases. Laboratory tests showed Hb = 65 g/L (120-170), WBC = 5.3×109/L (4-10), Platelet = 401×109/L (150-450), MCV = 90 fl (80-100), Hct = 0.34 (0.36-0.42), and normal differential count. In biohumoral status, the following pathological values were found: ESR = 90 mm/h, urea = 17.9 mmol/L (2.5-7.5), Cr = 476 μmol/L (53-106), ClCr = 13.3mL/min, tubular proteinuria=0.82 g/24h without erythrocyturia, total protein = 60 g/L (62-81), albumin = 6 g/L (40-55), Fe = 4.6 μmol/L (7-26), TIBC = 36.3 μmol/L (44.8-75.1), LDH = 590 IU/L(160-320). Immunological analyses showed CRP 28.9 mg/L (<9), ANA negativity, RF 37.3 IU/mL (<25) WR 1:40+. Virusological and bacteriological analyses were normal. Hemostasis screening did not display any detectable abnormalities. X-ray of the lungs and heart was normal, too. Abdominal echosonography showed craniocaudal splenomegaly of 14 cm, ascites and enlarged kidneys, the right of 14.5 cm and the left of 13.7 cm, without corticomedullary border. Echosonography of the heart showed pericardial effusion. Thereupon, ultrasound-guided biopsy of kidneys was performed and pH finding indicated tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN). There were no criteria for connective tissue disease, drug-or infection-induced acute TIN. The diagnosis of idiopathic acute TIN with polyserositis was made and urbason at pulse doses of 3×1 g/d was administered, followed by prednisolone 45 mg/d for another month. After a short recovery, in May 1999, the patient was rehospitalized for jaundice, pains under the right costal arch, nausea and vomiting. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showed extra-luminal compression of ductus pancreaticus and ductus hepaticus which was moved to the right, while choledochus was filamentary narrowed distally from the site of compression. Proximal of stricture was a huge biliary duct dilatation with changes of intrahepatical biliary ducts [as in cholangitis]. Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen and small pelvis revealed the enlarged retroperitoneal and mesenterial lymph glands, thickened small intestine wall, extremely augmented kidneys with destroyed corticomedullary structure, as well as infiltration of the right sacral bone (Figure 1). Choledochotomy and cholecystectomy with choledochojejunostomy and biopsy of mesenterial lymph glands and adipous tissue were performed. Pathohistological (PH) and immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses of mesenterial lymph nodes and adipous tissue from transfersal mesocolon showed the PTL infiltration (anti-CD45RO+, anti-CD43+, CD3+ as well as anti-EMA- /epithelial membrane antigen/, anti-vimentin-) (Figure 2). The revision of renal PH findings substantiated the diagnosis (Figure 3). Neoplastic lymphoid cells were also found in the ascites (Figure 4). Antiendomysial serum IgA antibodies (EmA) in high titer +++ were (Figure 5) detected by indirect immunofluorescence on monkey oesophagus. Anti-nuclear, anti-microsomal, anti- tireoglobulin antibodies were negative and serum levels of IgM, IgG and IgA were normal. Upon complete staging of the disease, it was verified that it was EATCL with infiltration of intestines, intraabdominal lymph glands, kidneys and sacral bone (CS IVB). The patient was transferred to the Institute of Hematology, where she received chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide (1200 mg, D1), doxorubicin (90 mg, D1), vincristine (2 mg, D1), prednisolone (100 mg, D1-5. On the second day of therapy, the patient died manifesting the signs of cardiorespiratory insufficiency and picture of pulmonary embolism, most probably caused by tumor cells.

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance imaging shows extremely augmented kidneys.

Figure 2 Neoplastic mesenterial lymph node infiltration with staining of lymphoma cells (APAAP with anti-CD3 Ab x 400).

Figure 3 Renal infiltration with monomorphous lymphoid infiltration (H&E, x 40).

Figure 4 Neoplastic lymphoid cells in ascites (MGG, x100).

Figure 5 IgA antiendomysial antibodies surrounding sarcolemma of smoth muscle fibers in lamina muscularis mucosae of monkey esophagus (IIF, x 400).

DISCUSSION

EATCL is a relatively rare disease with the incidence rate less than 1% of all NHL[20]. By nature, it is aggressive whether it occurs as de novo disease or results from long-term untreated or refractory CD. Usually, the jejunum is involved with presence of multiple circumferential ulcerations but without formation of homogenous tumor mass. In addition, the involvement of mesenterial lymph glands is frequently seen. In fact, refractory CD is considered as lymphoma of low grade malignancy resulting from clonal expansion of intraepithelial lymphocytes and represents an intermediate stage between CD and EATCL[21,22].

The moment when CD converts to intestinal lymphoma is sometimes difficult to recognize. Diffuse bilateral infiltration of the kidneys by lymphoma cells is a rare but well documented cause of ARF[23]. The diagnosis should be suspected in a patient with ARF, bilateral enlargement of the kidneys, minimal proteinuria, non-specific findings on urine analysis, and absence of other features (fever, skin rush, eosinophilia) typical of drug-induced TIN. Renal imaging techniques may suggest the possibility of lymphomatous infiltration, but only renal biopsy or autopsy can provide a definitive diagnosis[24]. Diffuse bilateral renal cell lymphoma sometimes presents as ARF of unknown cause. Signs of extrarenal lymphomatous involvement were detected in 44% patients at the time of kidney biopsy or shortly thereafter[25] and often clinically mimic primary renal disease or systemic connective disease.

In our patient who was diagnosed with CD 20 years prior to the development of lymphoma, CD was in subclinical form for years. This is a key point for misdiagnosis of TIN instead of lymphoma renal infiltration. At the time of aggravation of general condition, renal failure with signs of TIN and polyserositis predominated in the clinical picture of disease. Short-term improvement after the corticosteroid treatment was followed by stasis icterus but without any symptoms typical of intestinal lymphoma. Diagnostic dilemma was resolved by complete PH and IHC examinations of bioptic specimens of mesenterial lymph glands and mesocolic adipous tissue tumor. Time loss due to unrecognized intestinal lymphoma, and dissemination into abdominal organs and small pelvis, brought about the extreme progression of the disease. Because of huge tumor mass, it led to lethal outcome with pulmonary embolism by tumor cells after the chemotherapy. Actually, this was a long-term CD, which like the premalignant condition gave rise to highly aggressive T-cell lymphoma with striking propagation and short survival median.

Our case demonstrated that in this point of view, serological follow-up was very useful and could reduce the time of possible subclinical or refractory CD. It is necessary to determine serum IgA EmA not only to monitor the activity but also to predict the gluten-free diet compliance. IgA EmA should disappear after a gluten free diet is started and about 90% of patients who have characteristic findings of CD respond to complete dietary gluten restriction[26]. In the early stages of EATCL, serological, immunohistochemical and molecular biological analyses may lead to the correct diagnosis and better prognosis[27].

The target cells in EATCL as a member of uniform subclass T-cytotoxic lymphocytes are also target cells in the intestinal lesion in CD patients, indicating that the evolution of genetically controlled autoimmune disease as pre-malignant condition to highly risk and aggressive lymphoma of small intestine is the evidence confirming that autoimmunity is a risk factor for malignancy.

Our case revealed very aggressive atypical clinical onset of EATCL patient, which was presented as ARF without intestinal symptoms at presentation. This is a first case in published literature, which describes ARF as an initial manifestation of EATCL. Although it was a case of misdiagnosis of idiopathic TIN with polyserositis instead of lymphoma, our study has confirmed that subjects with persistent high IgA EmA should be regularly re-examined concerning possible evolution of CD towards EATCL. Although good serological predictors are not yet available, IgA EmA assessment may help to detect individuals at higher risk to develop EATCL.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Bi L