Published online Apr 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i14.2288

Revised: October 10, 2005

Accepted: November 18, 2005

Published online: April 14, 2006

AIM: To study the expressions of gastrin (GAS) and somatostatin (SS) in gastric antrum tissues of children with chronic gastritis and duodenal ulcer and their role in pathogenic mechanism.

METHODS: Specimens of gastric antrum mucosa from 83 children were retrospectively analyzed. Expressions of GAS and SS in gastric antrum tissues were assayed by the immunohistochemical En Vision method.

RESULTS: The expressions of GAS in chronic gastritis Hp+ group (group A), chronic gastritis Hp- group (group B), the duodenal ulcer Hp + group (group C), duodenal ulcer Hp- group (group D), and normal control group (group E) were 28.50 + 4.55, 19.60 + 2.49, 22.69 + 2.71, 25.33 + 4.76, and 18.80 + 2.36, respectively. The value in groups A-D was higher than that in group E. The difference was not statistically significant. The expressions of SS in groups A-E were 15.47 + 1.44, 17.29 + 2.04, 15.30 + 1.38, 13.11 + 0.93 and 12.14 + 1.68, respectively. The value in groups A-D was higher than that in group E. The difference was also not statistically significant.

CONCLUSION: The expressions of GAS and SS are increased in children with chronic gastritis and duodenal ulcer.

- Citation: Xie XZ, Zhao ZG, Qi DS, Wang ZM. Assay of gastrin and somatostatin in gastric antrum tissues of children with chronic gastritis and duodenal ulcer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(14): 2288-2290

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i14/2288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i14.2288

Infantile chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer are frequently encountered in children. The gastroscopic diagnostic rate accounts for 85%-94.5% for chronic gastritis and 8%-22% of peptic ulcer. The causes of these diseases and pathogenic mechanisms are not completely clear. The digestive tract is the largest and most complicated secretory organ in human bodies. Gastrointestinal hormones not only play an important regulatory role in secretory and motor functions of the digestive tract, but also have an important effect on its growth, development and damage repair. It has been shown that abnormity of GAS and SS plays an important role in causing chronic gastritis and duodenal ulcer in children[1]. We examined the expression of GAS and SS in gastric antrum tissues from 83 children with chronic gastritis and duodenal ulcer using immunohistochemical method (Table 1). The changes in GAS and SS and Hp infection and their effect on chronic gastritis and duodenal ulcer in children were studied, in order to provide a theoretical basis for the gastrointestinal hormone drugs used in the treatment of chronic gastritis and duodenal ulcer in children.

| Groups | n | GAS | SS |

| Chronic gastritis Hp+ group | 20 | 28.50 ± 4.55 | 15.47 ± 1.44 |

| Chronic gastritis Hp- group | 19 | 19.60 ± 2.49 | 17.29 ± 2.04 |

| Duodenal ulcer Hp+ group | 21 | 22.69 ± 2.71 | 15.30 ± 1.38 |

| Duodenal ulcer Hp- group | 12 | 25.33 ± 4.76 | 13.11 ± 0.93 |

| Normal control group | 11 | 18.80 ± 2.36 | 12.14 ± 1.68 |

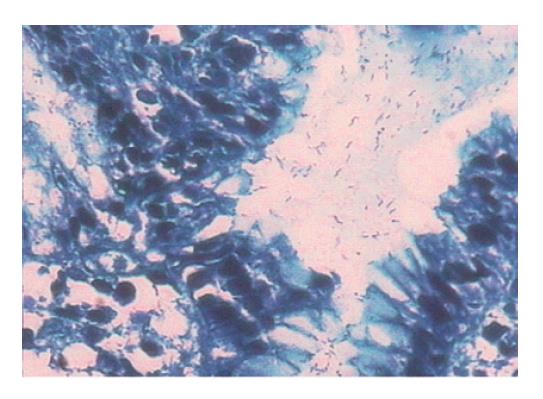

Paraffin specimens of gastric antrum mucosa were obtained from the children during the period of 2002-2003 in our hospital. All the subjects did not receive gastrointestinal kinetic drugs and H2 receptor agonists. The biopsy tissues were fixed in 10% neutral formalin, routinely dehydrolyzed, paraffin-embedded and cut into sections which were stained with HE. Hp infection was diagnosed by rapid urease test and microscopy. The cases were regarded as strongly positive when the test paper of urease test became cherry-red from yellow within 1 min, weakly positive when the test paper turned cherry-red and negative when the test paper did not change color. The weakly positive specimens were excluded from the study. Microscopy at 400 × magnification revealed positive rod-shaped bacteria in the gastric pit and body (Figure 1). A case was considered Hp+ when it was positive in the two methods and Hp- when it was negative in the two methods. The experimental samples were divided into group A: chronic superficial gastritis, Hp+; group B: chronic superficial gastritis, Hp-; group C: duodenal ulcer, Hp+; group D: duodenal ulcer, Hp-; and group E: normal gastric antrum tissues with no obvious pathologic changes, Hp-. Patients with other diagnoses such as chronic atrophic gastritis were excluded from the study. Thirty experimental samples were then randomly taken from each group. After specimens from patients with intestinal metaplasia or superficial specimens and very tiny specimens were excluded, the exact number of samples used in groups A-E was 20, 19, 21, 12 and 11, respectively.

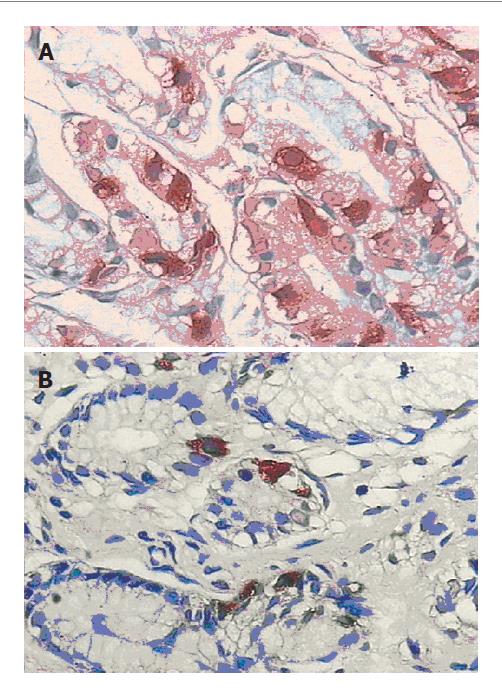

Immunohistochemical method (En Vision method) was used and each paraffin sample was labeled with GAS and SS, respectively. When GAS and SS were located in cytoplasm, samples displaying brownish yellow particles or balls were regarded as positive. Positive cell bands of each sample were observed and lymph follicle areas were avoided. The number of positive cells within a sample was counted.

Statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS10.0 software package. The count of GAS and SS was in conformity with a normal distribution and expressed as mean ± SD. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

GAS and SS expression was higher in groups A-D than in group E with no significant difference (Figures 2A, 2B).

GAS is a kind of peptides secreted by G cells located in the gastric antrum and duodenal mucosa, whose main function is to stimulate gastric acid secretion. It is of physiopathologic importance in occurrence of duodenal diseases. Since Levi et al[2] found that Hp could lead to increase in serum GAS of Hp-infected persons, a flood of studies have found that the level of serum GAS is higher in Hp positive children with chronic gastritis than in Hp negative children. After anti-Hp treatment, the level of GAS in children decreases[3]. It is held that Hp infection may lead to increase in GAS released by G cells, making damages to gastric and duodenal mucosa. Hp stimulates inflammatory cell factors such as IL-21, IL-28, TNF, IFN and G cells to release GAS[4]. SS secretion is reduced by the inhibition of D cell functions by Hp infection, which results in decrease in inhibition of G cells by SS[5]. The increased Hp level on surface of the gastric antrum by ammonia interferes with the normal feedback mechanism of inhibition of GAS secretion by acids in the stomach, which results in increase in GAS secretion. Hp or its products (ammonia or peptides) have direct effects on G cells[6]. The present study showed that the expression of GAS in chronic gastritis Hp+ group (group A) and chronic gastritis Hp- group (group B) was higher than that in the normal control group (group E) and the expression of GAS in chronic gastritis Hp+ group (group A) was higher than that in chronic gastritis Hp- group (group B), indicating that chronic inflammation, especially Hp infection, can result in increase in GAS, which may be one of the pathogenic mechanisms underlying chronic gastritis.

The causes of duodenal ulcer are associated with various factors. Digestion of local mucosal tissues by gastric acid and peptase is an important cause of ulcer occurrence. Therefore, ulcer is closely associated with GAS. Smith et al [7] reported that the basal and postprandial concentrations of serum GAS are increased in adults with duodenal ulcer. Wu et al [8] reported that the level of serum GAS in children with duodenal ulcer was much higher than that in the control group. Increased GAS release, which results in increased secretion of gastric acid and occurrence of ulcer, is one of the mechanisms underlying duodenal ulcer in children.

SS widely exists in the gastrointestinal tract, with its highest concentration in the gastric pylorus area. D cells in the gastric pylorus secrete SS. SS has an inhibitory effect on secretion of gastrointestinal hormones such as GAS, motilin and gastric acid. Therefore, SS is regarded as a defensive factor for local mucosa.

Geller et al[9] showed the level of fasting serum SS was higher in DU patients than in normal persons, suggesting that the increased level of SS in DU patients is a compensatory mechanism caused by the feedback stimulation with high concentrations of acids. Lucey et al [10] showed hydrochloric acid can increase the level of SS in DU patients. Erton et al[11] found that high concentrations of acids could stimulate SS release. Mihaljevic et al[3] showed that the level of serum SS in Hp+ patients was lower than that in Hp- patients. Zavros et al[12] found that the content of SS in specimens of gastric mucosa from chronic gastritis Hp+ patients was 6 times lower than that in chronic gastritis Hp- patients. Chavialle et al[13] showed that the content of SS in gastric antrum mucosa of DU patients was lower than that in the control group. However, Jensen et al [14] reported that the content of SS in bulb mucosa of DU patients was higher than that in the control group. Therefore, the true meaning of changes in the content of SS in gastroduodenal mucosal tissues of DU patients and their role in the pathogenic mechanism of DU are unclear. The extent of various damages and regulating function may be different in human tissues during different phases. Our study showed that the number of SS positive cells in groups A-D was higher than that in group E, indicating that inflammation, especially Hp infection, can stimulate release of GAS and SS as well as secretion of gastric acid under high concentrations of acids. The reason why there was no significant difference may be the insufficient cases of experiment. Due to relatively small amount of biopsy tissues from superficial or relatively superficial mucosa and the abandoned sections whose immunohistochemical staining was not clear, the valid cases for the experiment were greatly reduced. Besides, because the size of biopsy tissues from children was smaller than that from adults, the observed number of cells was also smaller. Therefore, our studies necessitate further efforts to perfect them.

| 1. | Haruma K, Sumii K, Okamoto S, Yoshihara M, Sumii M, Kajiyama G, Wagner S. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with low antral somatostatin content in young adults. Implications for the pathogenesis of hypergastrinemia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:550-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Levi S, Beardshall K, Haddad G, Playford R, Ghosh P, Calam J. Campylobacter pylori and duodenal ulcers: the gastrin link. Lancet. 1989;1:1167-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dawes C, O'Connor AM, Aspen JM. The effect on human salivary flow rate of the temperature of a gustatory stimulus. Arch Oral Biol. 2000;45:957-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Calam J. The somatostatin-gastrin link of Helicobacter pylori infection. Ann Med. 1995;27:569-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sumii K, Sumioka M, Yoshihara M, Tari A, Haruma K, Kajiyama G. Somatostatin in gastric juice in normal subjects and patients with duodenal ulcer. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:1020-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | DelValle J, Yamada T. Amino acids and amines stimulate gastrin release from canine antral G-cells via different pathways. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:139-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Smith JT, Pounder RE, Nwokolo CU, Lanzon-Miller S, Evans DG, Graham DY, Evans DJ. Inappropriate hypergastrinaemia in asymptomatic healthy subjects infected with Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1990;31:522-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wu Xiuying, Ou Biyou, Chen Xiaoxiao. Determination of the contents of gastrin, motilin and somatostatin in blood of DU children with chronic gastritis. Zhonghua Erke Zazhi. 2000;38:685-688. |

| 9. | Fujii M, Shirasawa Y, Kondo S, Sawanobori K, Nakamura M. Cardiovascular effects of nipradilol, a beta-adrenoceptor blocker with vasodilating properties. Jpn Heart J. 1986;27:233-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lucey MR, Wass JA, Fairclough PD, O'Hare M, Kwasowski P, Penman E, Webb J, Rees LH. Does gastric acid release plasma somatostatin in man. Gut. 1984;25:1217-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ertan A, Arimura A. Regulation of gastric somatostatin secretion. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:847-848. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Zavros Y, Paterson A, Lambert J, Shulkes A. Expression of progastrin-derived peptides and somatostatin in fundus and antrum of nonulcer dyspepsia subjects with and without Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:2058-2064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chayvialle JA, Descos F, Bernard C, Martin A, Barbe C, Partensky C. Somatostatin in mucosa of stomach and duodenum in gastroduodenal disease. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:13-19. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Jensen SL, Holst JJ, Christiansen LA, Shokouh-Amiri MH, Lorentsen M, Beck H, Jensen HE. Effect of intragastric pH on antral gastrin and somatostatin release in anaesthetised, atropinised duodenal ulcer patients and controls. Gut. 1987;28:206-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Cao L