INTRODUCTION

Brunner’s glands, described by the anatomist Brunner in 1688, are submucosal mucin-secreting glands. They are predominantly localized in the duodenal bulb and proximal duodenum and progressively decrease in size and number in the distal portions. Brunner’s glands exert a physiological “anti-acid” function by secreting alkaline fluid composed of mucin which protects the duodenal epithelium from the acid chime of the stomach[1]. Furthermore, they produce and secrete “enterogastrone”, an enteric hormone inhibiting gastric acid secretion.

Brunner’s gland adenoma (BGA), firstly described by Curveilheir in 1835, is a benign tumour arising from the Brunner’s glands that exceptionally may evolve towards a malignant transformation[2-4]. BGA is an extremely rare tumour with an estimate incidence of 0.008% reported in a single series of 215 000 autopsies[1]. At present, < 200 cases have been reported in the world medical English literature.

Here, one case of large BGA managed by endoscopic resection is reported together with a review of the pertinent literature.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year old female was referred to our Gastroenterology Unit due to episodes of epigastric discomfort over the past few months. Past medical history included appendicectomy performed during childhood, cholecystectomy for gallstones performed 4 years previously and a self-limiting single episode of melena occurred two months previously. The patient denied weight loss or use of non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Clinical examination and routine blood tests were normal. Esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGDS) demonstrated normal esophagus and stomach. A large pedunculated polyp, 3 cm × 4 cm in size, completely occupying the duodenal bulb was found. Healing microerosions were present on the mucosa. Histological examination of the multiple biopsy specimens obtained during EGDS, suggested “Brunner’s gland hyperplasia” in a context of mild chronic gastritis without evidence of Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection.

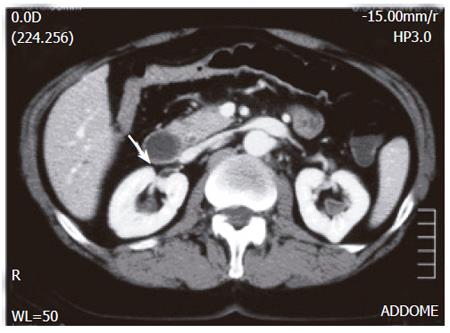

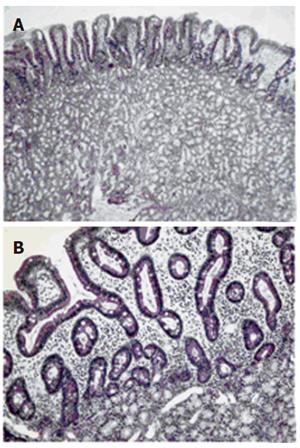

Abdominal CT-scan confirmed the presence of a polypoid mass originating in the mucosa of the duodenal bulb and extending to the second portion of the duodenum for about 4 cm, without evidence of duodenal wall infiltration (Figure 1). Endoscopic resection was carried out to remove the duodenal mass. Histological examination revealed closely packed Brunner’s glands and ducts embedded in a fibrous stroma with a moderate degree of lymphocyte and monocyte infiltration (Figures 2A and 2B). A diagnosis of Brunner’s adenoma was made. During the 6-month follow-up, the patient remained symptom-free and no further episodes of melena occurred. EGDS did not find any residual lesion.

Figure 1 Evidence of polypoid mass in duodenal bulb extending to second duodenal portion (arrow).

Figure 2 Gland hyperproliferation extending beyond muscolaris mucosae reaching lower portion of duodenal villi with irregular and squat profile of these structures (A) (H&E, original magnification X4) and detail of interface between Brunner’s gland proliferation and duodenal mucosa with absence of muscularis mucosae and irregular profile of villi (B) (E&E, original magnification X20).

DISCUSSION

BGA has a tendency to be predominant in the fifth or sixth decade of life with equal gender distribution [5]. Clinical presentation is variable. However, the majority of cases are asymptomatic or present with non specific, vague symptoms such as abdominal pain or discomfort, nausea or bloating. BGA is usually an incidental finding during imaging studies or EGDS[5].

In symptomatic patients, the most common clinical presentations are gastrointestinal bleeding (37%) and obstructive symptoms (37%)[5]. Gastrointestinal bleeding manifests in the majority of cases as chronic loss of blood with iron deficiency and anaemia[6]. Less frequently, when erosion or ulceration of the tumour occurs, patients can present with melena or haematemesis. These findings are usually described in BGA occurring beyond the first portion of the duodenum, probably because these lesions are subjected to more stress and vascular damage from gastrointestinal motility[6]. In our case, the patient referred to our unit for a self-limiting episode of melena and showed a large polyp at EGDS with a short peduncle localised in the duodenal bulb with an ulcer scar on the surface.

Aetiology and pathogenesis of BGA still remain to be elucidated. Due to the “anti-acid” function of Brunner’s glands, it has been postulated that an increased acid secretion could stimulate these structures to undergo hyperplasia[7]. Franzin et al [8] have reported an association between BGA and hyperchlorhydria in patients with chronic gastric erosions and duodenal ulcers, but Spellberg et al[9] have not found regression of the lesion with acid secretion inhibitors[9]. A second hypothesis suggests that this lesion is of inflammatory origin due to the presence of a dense inflammatory cell infiltration[10]. Since lymphocytes are usually present in the normal submucosa of the intestinal tract, the presence of inflammatory foci in the BGA is not sufficient to sustain the “inflammatory hypothesis”. Finally, it has been suggested that H pylori infection may play a role in the pathogenesis of BGA. In a recent study involving 19 100 subjects, H pylori infection was found in five out of seven (71%) BGA cases[11]. In our patient, H pylori infection was not found. The extreme rarity of BGA and the high prevalence of H pylori infection in general population do not allow us to draw a clear pathogenetic link. At present, the most accredited pathogenetic hypothesis remains that BGA is a duodenal dysembryoplastic lesion or hamartoma[12].

The duodenal bulb is the most frequent localization of BGA (57%) [13]. In the majority of cases, these lesions develop into a polypoid mass, usually pedunculated (88%), being 1 to 2 cm in size[14] while few cases reaching several centimetres as the ”giant BGA” have been reported[6,15-18]. On the other hand, lesions < 1 cm are referred to as Brunner’s gland hyperplasia[19].

Diagnosis of BGA is not always easy at present. Radiological findings (X-ray and computed tomography) are often non specific[12]. Indeed, the duodenal filling defect can mimic several other lesions, such as leiomyoma, lipoma, lymphoma, aberrant pancreatic tissue or carcinoid tumours[20]. Computed tomography is useful only to confirm the absence of extra-luminal extension of BGA[20]. Diagnosis can be obtained by histological examination of the excised mass. Traditional endoscopy of pinching biopsies is usually negative since the biopsy forceps are unable to reach the tumoral tissue localized completely in the submucosa layer [21]. In our case, diagnosis was made on endoscopic biopsy samples of duodenal mass, because Brunner’s gland hyperproliferation was extended beyond muscularis mucosae reaching lower portion of duodenal villi (Figure 2).

Endoscopic or surgical removal of BGA has been suggested to prevent the development of complications (haemorrhage, severe anaemia, obstruction or intussusception). Endoscopic polypectomy represents the ideal approach, which is more cost-effective and less invasive of the abdominal surgery [22,23]. However, the success depends on site and size of the BGA and presence of a peduncle. Several cases of successful endoscopic resections have been reported [12,24-26]. In our case, even though the lesion was large (3 cm × 4 cm) with a short peduncle occupying entirely the duodenal bulb (Figure 1), endoscopic polypectomy was effective for the treatment of BGA, without complication and recurrence of the lesion during the 6-month follow-up.