Published online Jan 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.75

Revised: June 8, 2005

Accepted: June 18, 2005

Published online: January 7, 2006

AIM: To further assess of the incidence and localization of Crohn’s disease (CD) in a well-defined population during the 1990s and to evaluate the prevalence of CD on the 1st of January 2002.

METHODS: In a retrospective population based study, all 16-90 years old citizens of Stockholm County diagnosed as having CD according to Lennard Jones’ criteria between 1990 and 2001 were included. Case identification was made by using computerized inpatient and outpatient registers. Moreover private gastroenterologists were asked for possible cases. The extent of the disease and the frequency of anorectal fistulae were determined as were the ages at diagnosis. Further, the prevalence of CD on the 1st of January 2002 was assessed.

RESULTS: All the 1 389 patients, 689 men and 700 women, fulfilled the criteria for CD. The mean incidence rate for the whole period was 8.3 per 105 (95%CI 7.9 -8.8). There was no difference between the genders. The mean annual incidence of the whole study period for colorectal disease and ileocecal disease, was 4.4 (95%CI 4.0-4.7) and 2.4 (95%CI 2.1-2.6) per 105, respectively. Perianal disease occurred in 13.7% (95%CI 11.9-15.7 %) of the patients. The prevalence of CD was 213 per 100 000 inhabitants.

CONCLUSION: The incidence of CD has markedly increased during the last decade in Stockholm County and 0.2% of the population suffers from CD. The increase is attributed to a further increase of colorectal disease, while the incidence of ileocecal disease has remained stable.

- Citation: Lapidus A. Crohn’s disease in Stockholm County during 1990-2001: An epidemiological update. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(1): 75-81

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i1/75.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.75

Crohn’s disease (CD) is one of the major inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) that challenges many gastroenterologists in their everyday work. Although CD has been recognized for over 70 years[1], its etiology still remains unclear. An explanatory factor for the unsolved etiology may be the heterogeneous appearance of the disease.

Although descriptive epidemiological studies can hardly prove the etiology of the disease, they are very important in the pursuit of risk factors that can be further assessed in etiological epidemiological studies. Furthermore, they are useful for planning the health care system, development of new pharmaceuticals and therapeutic endeavors.

The former increasing incidence of CD in countries located in the north[2-5] seems to have leveled off during the eighties. Nevertheless, the incidence continued to increase in Scotland and Iceland during the eighties and early nineties[6,7]. An increasing incidence of CD has also been assessed in former low-incidence countries in southern Europe, Asia, and Japan[8-10]. Although numerous epidemiological studies of CD have been performed since the 1960s, there are only few population-based studies that have explored the incidence of CD during the last decade[11-14].

When Burrill B Crohn and his colleagues first described CD in 1932[1], the most common site of the disease was the ileocecal area. It was not until 1960 that CD localized to the colon and/or rectum was regarded as an entity of its own[15], unrelated to ulcerative colitis (UC). Pure colorectal disease has become more common over the years. In a previous survey of patients diagnosed with CD in Stockholm between 1955 and 1989, the proportion of colorectal disease doubled from 14% to 32% during the study period[16]. This phenomenon has been reported from other areas as well[6,7,17].

As the mortality due to CD is low[18], an increasing number of patients will suffer from CD. There are scarce current prevalence rates available[13,19,20].

The primary aim of this study was to further assess the incidence and localization of CD in a well-defined population during the 1990s and to evaluate the prevalence of CD on the 1st of January 2002.

Stockholm County covers an area of 6 519 km2 with both urban and rural parts. The population increased from 1.64 to 1.84 million inhabitants between 1990 and 2001[21]. The number of individuals aged 16-90 years increased from 1.33 to 1.47 million during the same period and attributed to approximately 80% of the total population. The distribution between the genders was constant during the study period with a share of 49% men. The proportion of aliens was 9.4% in 2001.

There were 9 major hospitals and further 13 established gastroenterologists in private practice taking care of patients with IBD during the study period. The number of lower GI endoscopies (i.e, sigmoidoscopies and colonoscopies) performed in Stockholm County increased from 4 787 to 19 778 per year between 1993 and 2001[22].

In Stockholm County, there has been a computerized central registration of all diagnoses for inpatients since 1969. Since 1993, diagnoses have also been successively registered for outpatients and all patients attending the outpatient clinic at the hospitals. The general practitioners have got their diagnoses registered since 1996. Diagnoses were registered according to the International Statistical Classification of Disease (ICD-9 1987-1996, ICD-10 1997 and onwards).

A survey of possible cases was made from the records registered as CD (ICD code 555 and K.50) in the inpatient register between 1990 and 2002 and the outpatient register between 1993 and 2002.

Gastroenterologists in private practice were asked about possible cases and their colonoscopy and histology reports were assessed. All records (paper, microfilmed, and electronic) were retrospectively scrutinized. Patients with an established probable or definite diagnosis of CD according to Lennard Jones’ criteria[23] were included in the study. Included patients should be citizens of Stockholm County and were diagnosed as having CD between 1st January 1990 and 31st December 2001. Patients younger than 16 years at diagnosis were not included in the study.

The diagnosis of CD and extent of the disease at diagnosis were based on radiological and/or endoscopical reports including macroscopic and microscopic findings as previously described in detail[16].

Date of diagnosis was defined as the first examination revealing signs of CD. If the diagnosis was changed from UC to CD, the first diagnosis date of IBD was considered. Date of presentation of symptoms which are consistent with IBD was approximated to months with a certainty expressed as either the first or the 15th day of the month. In cases, where only the year could be estimated, the date of onset was set as the 1st of July.

The type of diagnostic examination(s) performed at the time for diagnosis was noted. The localization of CD was determined based on these diagnostic examinations and classified into five groups: oro-jejunal disease, small bowel disease (inflammation of the small bowel excluding the distal 30 cm of the terminal ileum), ileocecal disease (inflammation including the distal 30 cm of the ileum with or without isolated involvement of the cecum), ileocolonic disease (continuous or discontinuous inflammation of the ileum and colon) and colorectal disease (inflammation in the colon only and/or rectum). The group of oro-jejunal disease consisted of patients with solely oro-jejunal disease and patients with mainly oro-jejunal disease but also inflammation in a more distal part of the intestine.

The extent of colorectal disease was further classified into three groups. For assessment of the disease extent, the colon was schematically divided into four areas consisting of the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid respectively. Colonic disease could either be segmental disease with the involvement of one, two or three of the four schematic areas, left-sided disease extending proximally from the rectum but not beyond the splenic flexure, or total colonic disease with inflammation in all the four areas. Patients with segmental or total colonic disease could have either rectal involvement or rectal sparing. Anorectal fistulae included fistulas and abscesses in the rectum, anal canal or perianal area that appeared before the diagnosis of CD, at the time of diagnosis or at any time during the follow-up period.

If data concerning the parameters mentioned above were uncertain to assess, the data were labeled as unreliable and excluded from actual analysis.

The cases of CD as well as the population were grouped into 15-year age specific groups: 16-30 years, 31-45 years, 46-60, 61-75, and 75-90. Information about the population in Stockholm County was obtained from the National Central Statistical Register[21].

Incidence rates were calculated for 2-year periods and expressed as annual incidence rates. For each 2-year period, the age specific incidence was calculated by dividing the number of cases by the number of person years in each age group. The population was not adjusted (i.e, subtracted) for previous incidence cases. Calculations were made separately for men and women. The annual incidence was adjusted for sex and age by using the population in Stockholm County in 1995 as a standard population. Incidence rates were expressed as cases per 105 inhabitants with a 95% confidence interval (CI) based on the assumption that the number of cases follows a Poisson distribution. A Poisson model (Breslow) was used to study the relationship between sex, calendar year, age and the risk of CD. The hazard function of individuals aged 16-88 years was assumed to be exp [β0+β1 ∙ minimum (age, 45)+β2 ∙ maximum (0, minimum (age-45, 70-45)+β3 ∙ maximum (0, age-70)+β4 ∙ minimum (calendar year-1990, 6)+β5 ∙ maximum (0, calendar year-1996)+β6 ∙ sex]. The coefficients β1, β2, β3, β4, β5, and β6 reflected the trends of the risk, β1 = β2 = β3 = β4 = β5 = β6 = 0 corresponded to no change of risk[24].

Time between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis was calculated as the median.

The extent of disease at diagnosis was assessed as incidence rates as well as proportions, i.e. percentages of the total number of cases. Comparison between men and women with respect to the localization of disease was performed by χ2 test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for comparison of age at onset and calendar time at onset between localization of disease. If a significant importance of localization was obtained, each localization was compared to all the others by use of Fisher’s permutation test.

The probability of anorectal fistulae and rectal involvement, depending on age, sex, and localization of the disease, was estimated by the use of logistic regression.The two-tailed tests were used.

The Ethics Committee at Huddinge University Hospital approved the study.

Basic data are shown in Table 1.

| 1990-1991 | 1992-1993 | 1994-1995 | 1996-1997 | 1998-1999 | 2000-2001 | 1990-2001 | |

| Total | 174 | 219 | 234 | 286 | 235 | 241 | 1389 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 74 | 114 | 112 | 143 | 127 | 119 | 689 |

| Female | 100 | 105 | 122 | 143 | 108 | 122 | 700 |

| Age at diagnosis | |||||||

| 16-30 | 60 | 86 | 89 | 121 | 87 | 88 | 531 |

| 31-45 | 49 | 52 | 62 | 66 | 57 | 56 | 342 |

| 46-60 | 27 | 44 | 40 | 47 | 51 | 61 | 270 |

| 61-75 | 29 | 27 | 33 | 40 | 32 | 26 | 187 |

| 76-90 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 59 |

| Localization of disease at diagnosis | |||||||

| Oro-jejunal | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 30 |

| Small bowel | 8 | 14 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 49 |

| Ileocecal | 58 | 55 | 61 | 85 | 61 | 73 | 393 |

| Ileocolonic | 15 | 28 | 38 | 35 | 32 | 41 | 189 |

| Colorectal | 91 | 118 | 121 | 150 | 130 | 118 | 728 |

Altogether 1 389 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. A total of 569 patients (41%) had a definite diagnosis of CD and 820 patients (59%) had a possible diagnosis of CD according to Lennard Jones’ criteria.

Information regarding the onset of symptoms, methods of diagnosis, occurrence of anorectal fistulae and rectal involvement was not available in 26, 9, 96, and 31 patients respectively. Twenty-eight percent of the patients were prescribed azathioprine or equivalent immunosuppressive medicine at any time during the follow-up.

The median time between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis was 6.5 mo (range 0-376 mo) for the whole study period. Patients with small bowel disease and ileocecal disease had a longer median time to diagnosis (12.8 and 10.9 mo, respectively) than patients with ileocolonic and colorectal disease (6.1 and 5.9 mo, respectively) (P < 0.005).

The diagnostic procedures performed between the first-time visit and the diagnosis of CD are shown in Table 2.

| Main examination, n (%) | Total number, n (%) | |

| Colonoscopy | 690 (49.7) | 690 (49.7) |

| Ileocolonoscopy | 285 (20.5) | 285 (20.5) |

| Large bowel barium enema | 138 (9.9) | 250 (18.0) |

| Enteroclysis | 62(4.5) | 602 (43.3) |

| Surgery | 82 (5.9) | 141 (10.2) |

| Rigid sigmoidoscopy | 20 (1.4) | NA |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 12 (0.9) | 46 (3.3) |

| Miscellaneous | 45 (3.2) | |

| Unknown | 55 (4.0) |

If a colonoscopy/ileocolonoscopy was performed, the examination was considered as the “main examination”. Otherwise, the examination that provided most information for diagnosing and evaluation of the extent of disease was labeled as “main examination”. The total number of procedures reflected how many patients underwent each specific examination.

Altogether 70.2% of the patients underwent an endoscopic examination of the colon and the terminal ileum was inspected in 29.2% of these patients. An enteroclysis was performed in 43% of all patients. Six percent of the patients were diagnosed by surgery. The remaining patients underwent only flexible/rigid sigmoidoscopy or miscellaneous examinations.

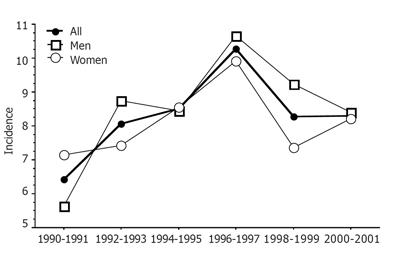

The mean annual incidence rate for the entire study period was 8.3% (95%CI 7.9%-8.8%) per 100 000 inhabitants. The mean annual incidence rate was 7.7% (95%CI 7.1-8.3%) and 8.9 % (95%CI 8.3-9.6%), respectively, during the first and second half of the study period (Figure 1).

The mean increase in incidence per year was estimated to be 7.6% (95%CI 4.3-11.1%) between 1990 and 1996 with the highest increase (21.0%) between 1990 and 1992 (95%CI 5.4-38.8%) and (14.1%) between 1994 and 1996 (95%CI 1.8-27.8%). The maximum incidence rate was found in 1996-1997 with an annual mean of 10.3% (95%CI 9.1-11.5%) per 100 000 inhabitants. After 1996, the annual incidence decreased with a mean of 4.6% per year (95%CI 1.0-8.0%).

No statistical difference in incidence rates was found between men and women [8.6% (95%CI 7.9-9.2%) vs 8.1% (95%CI 7.5-8.7%) ] for the entire study period.

The highest age specific incidence was found among those aged 16-30 years at diagnosis with a mean incidence rate of 12.3 per 105 (95%CI 10.1-14.6) for the entire study period. A maximum incidence rate was observed during 1996-1997 with 17.1 per 105.

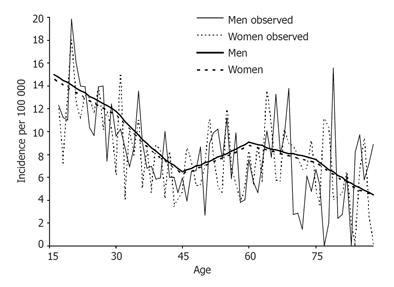

The relationship between age and the risk of CD by using a Poisson model, with the calendar year fixed to 1995, allowed the curve to bend at the arbitrary ages 30, 45, 60, and 75 years (Figure 2). With increasing age, the incidence decreased on an average of 1.7% per year between 16 and 30 years (P < 0.05) and 3.9% per year between 30 and 45 years (P < 0.001). Thereafter, the incidence increased again on a yearly average of 2.2% (P < 0.05) resulting in a second peak at the age of 60 years. In the elderly, the incidence rate decreased with an average of 1.2% and 3.9% per year between 60 and 75 years and over 75 years, respectively. Although the crude number of cases was lower in the older age groups, the bimodal peak in incidence was attributed to fewer person-years of follow-up in the older age groups compared with the younger age groups.

The proportion of patients older than 60 years at diagnosis was 17.7% and the proportion of all patients older than 75 years at diagnosis was 4.2%.

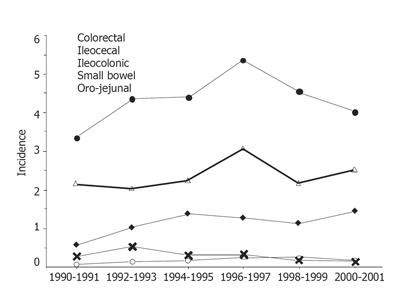

The incidence of CD by the extent of disease at diagnosis is shown in Figure 3.

The mean annual incidence in the whole study period for colorectal and ileocecal disease was 4.4% (95%CI 4.0-4.7%) and 2.4% (95%CI 2.1-2.6%), respectively. Corresponding figures for ileocolonic disease, small bowel disease and oro-jejunal disease were 1.1% (95%CI 1.0-1.3 %), 0.3% (95%CI 0.2-0.4%) and 0.2% (95%CI 0.1-0.2%), respectively. The only significant change over time was a decreasing incidence of small bowel disease throughout the study period (P < 0.05).

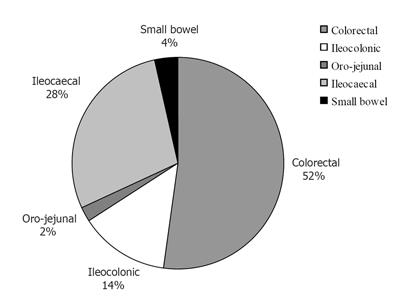

The overall proportion of colorectal and ileocecal disease was 52.3% (95%CI 49.7-55.0%) and 28.3% (95%CI 26.0-30.7%), respectively (Figure 4).

Age influenced the localization of CD at diagnosis. By comparing each disease localization to the others, patients with colorectal (P < 0.005) and small bowel disease (P < 0.005) were found to be older at diagnosis. In contrary, patients with ileocolonic (P < 0.001) and proximal disease (P = 0.055) were younger.

In pure colorectal disease, 36.3% of the patients had total colonic involvement, 40.2% had segmental disease and 23.5% had distal colorectal disease. Rectal inflammation at diagnosis was found in 67.8% of the patients with colorectal disease.

Distal colorectal disease was associated with a higher age at diagnosis (P < 0.005) and inversely total colonic disease was associated with a lower age at diagnosis compared to the rest of the patients (P < 0.001). Age did not influence the risk of segmental colorectal disease.

Gender had no influence on either disease localization or extent of colorectal disease at diagnosis.

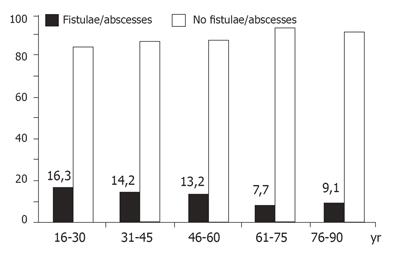

Anorectal fistulae occurred before or after the diagnosis of CD in 13.7% (95%CI 11.9-15.7%) of the patients whose data were assessable (n = 1 293). Gender as well as age had a significant impact on the occurrence of fistulae. Men were more likely to develop this kind of perianal disease than women (15.8% vs 11.6%, P < 0.05). The impact of age on anorectal fistulae is shown in Figure 5. The disease localization did not influence the frequency of fistulae.

Calculations were based on all adult patients ( > 16 years) with CD living in Stockholm County on the 1st of January 2002. Of the 1 389 patients diagnosed between 1990 and 2001, 71 patients were dead and 76 patients had moved out from the area. From the earlier cohort of 1 936 patients diagnosed during 1955-1989[16], 368 patients were dead and 239 patients had moved out. Twelve patients diagnosed in Stockholm before 1955 were still living in the area.

The present case identification survey revealed 327 patients diagnosed outside the Stockholm County, 128 patients diagnosed as UC before 1990 and later got the diagnosis changed from UC to CD and 97 patients diagnosed as CD during 1955-1989 but not included in the previous study[16] for unknown reasons. The prevalence was calculated by dividing the total number of patients with CD (3 135) by the adult population ( > 16 years) in Stockholm County (1 469 048). Accordingly, the prevalence of CD among the adults in Stockholm County on the 1st of January 2002 was estimated to be 213 per 100 000 inhabitants.

Including a former published study[16], the development of CD has now been documented for 45 years in Stockholm County. Thereby, one of the largest population based cohort of patients with CD in the world has been collected.

There are pros and cons regarding study designs. A prospective study may be considered more faultless but is unfeasible in a large study area with many hospitals and gastroenterologists. Shortcoming of a retrospective study can be lack of uniform diagnostic criteria or incomplete data collection. Patients in Stockholm are handled by a limited number of gastroenterologists and the diagnosis is therefore uniform. However, endoscopy has been escalating during the last years. A potential aim to retrospectively assess smoking habits in this study was abandoned due to the lack of reliable data, else sufficient data regarding different parameters were available. The pro of the present retrospective study is a long follow-up period when case ascertainment can be accomplished in the meantime.

The number of patients having a definite diagnosis of CD according to Lennard Jones’ criteria[23] in this study was lower (41%) than that in our previous study of CD in Stockholm (73%)[16]. One explanation could be that fewer patients underwent surgery. Specimens for histopathological examination were less available and thereby granulomas and submucosal signs of CD might be undetected. Some uncertainty may arise about the “probable” cases of CD according to Lennard Jones’ criteria. Case ascertainment was assured by scrutinizing the records retrospectively. By following the clinical course of CD, the diagnosis was further ascertained and all included cases were bonafide cases of CD.

Long-term incidence data are scarce in the literature from the late 1990s and onwards[12-14,25-27]. The incidence of CD among the adults in the present study was 70% higher than that in Stockholm during 1985-1989, with the highest incidence rate in 1996-1997. The registry of outpatients begun in 1993 and theoretically, the lower incidence found in 1990-1993 may represent an incomplete case ascertainment. Similarly, the drop-off in incidence during the last 4 years of the study could represent decreased ascertainment. However, all patients with CD in Stockholm are regularly followed up and should be identified sooner or later. Diagnoses are registered continuously and a marked delay of identification is unlikely, thus the case ascertainment is reliable.

A 55% increase of the incidence rate was also seen in Denmark where the incidence rate reached a maximum with approximately 10 per 105 in 1998-2002[12]. In Northern France, the incidence of CD increased 23% during a similar time period[14]. Still, the overall incidence rate is lower in France than in Stockholm. The highest incidence rates have previously been reported from North Eastern Scotland[7] and Manitoba in Canada[19] and now also from Sweden. This may illustrate a north-south gradient of CD that still exists although less pronounced than believed earlier[10]. The proportion of immigrants in Stockholm has not changed during the last decade and should therefore not affect the results[21].

CD is in general believed to affect women more frequently than men[14,17,28] although several studies have not found any difference[4,10]. This study confirmed earlier observations from Stockholm that gender does not influence the risk for CD[16].

CD mostly occurs in young adults, but can present itself at any time in life[29]. The age specific distribution in this study is consistent with some former studies with the highest incidence found among young adults and thereafter decreasing incidence rates with increasing age and a second peak in the elderly[7,16,17,30]. Nevertheless, the overall incidence among the elderly was substantially higher in this study compared with other studies[31,32].

Pure colorectal disease and small bowel disease are associated with a high age in contrast to our previous study where only small bowel disease was related to a high age at diagnosis. It has been suggested that smoking CD patients are more likely to develop small bowel disease than non-smoking patients[33]. Smoking habits were not evaluated in this retrospective study. However, one can speculate whether smoking was more tolerable in the society previously with an ensuing larger group of smokers among the older population. This assumption is strengthened by the fact that this entity of CD was the only one that decreased throughout the study period. Colorectal CD may be misclassified as ischemic colitis as well as diverticulosis. Both conditions are common in this age group. CD patients with concomitant diverticular disease are more likely to have granulomas but the misclassification should be limited by finding granulomas in other parts of the intestine[31]. Focal inflammation is one of the criteria of CD and distinguishes colorectal CD from UC.

This study focused on CD in adults since a study of children with IBD in northern Stockholm has been recently performed[27]. That study showed an increasing incidence of pediatric CD during the latter 1990s with an incidence of 8.4 per 105 in 1999-2001, thus identical rates were found in adults in the present study.

Anorectal fistulae, strongly associated with CD, have been reported in almost 40% of the patients, preferably in those with colorectal involvement[34]. Though patients with colorectal disease accounted for a huge proportion, the frequency of anorectal fistulae was low in the present study and on the whole, no relation was found between the frequency of fistulae and the disease localization. Inclusion of patients with mild colorectal disease might cause a dilution effect and a false low frequency of fistulae. A short follow-up period may be an alternative explanation and moreover, a general increased use of azathioprine may theoretically have prevented the development of fistulae.

The increasing incidence of CD is found in patients with solely colorectal disease. This entity of CD was first described in 1960 but an increasing proportion of colorectal CD was not reported before the late eighties[15].

The increase of colorectal disease can be attributed to a factual increase, a switch from UC to CD or more accurate diagnostic procedures. Unfortunately, there are no contemporary data regarding the development of UC in Stockholm County. However, Jacobsen et al [12] have shown a concomitant substantial increase of both UC and CD in North Jutland in Denmark between 1988 and 2002, which supports a factual increase of CD and contradicts a diagnostic shift from UC to CD. In contrast, the incidence of UC decreased by 17% in Northern France during a comparable time period[14]. If hypothetically, the decreasing incidence of UC should represent a corresponding increase of CD, still there would be a 50% increase of CD not due to a reclassification from UC to CD in Stockholm during the 1990s. The diagnosis of CD is partly based on histopathology and may vary between different pathologists[35]. In this study one single pathologist did most of the histopathological examinations.

The number of lower GI endoscopies performed in the area has increased fourfold[22]. This escalating access to medical service may have led to an examination of more patients with only mild symptoms. Patients with minor colonic inflammation that might have been overlooked with previously used barium enemas could therefore have attributed to the increased incidence of CD.

The median time between presentation of symptoms and diagnosis is rather similar to that found in 1955-1989[16]. The shortest time is found in patients with disease in the colon, while patients with small bowel disease have a longer period of symptoms before the diagnosis. This fact may illustrate the advantage of endoscopic technique in the diagnosis of IBD. Recently, the capsule endoscopy has been introduced in Sweden and is used to a limited extent[36]. With a more widespread use of this new technique, disease in the ileum may be more frequently detected[37]. Consequently an increased number of patients with small bowel CD will be diagnosed and thereby the incidence of CD will probably further increase in the future.

In conclusion, this follow-up study of CD in Stockholm County shows that the incidence increases by 80% from the 1980s to the 1990s. As much as 0.2% of the adult population in Stockholm County suffers from CD. The disease appears at any age and there is no predominance regarding gender. Colorectal CD is the most common localization and the frequency of anorectal fistulae is less evident than that in the past.

Mrs Monica Johansson is gratefully acknowledged for help with secretarial assistance. Mrs Helena Johansson is gratefully acknowledged for statistical support.

| 1. | Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Regional ileitis. A pathological and clinical entity. JAMA. 1932;99:1923-1929. |

| 2. | Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: a large, population-based study in Sweden. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:350-358. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lee FI, Nguyen-Van-Tam J. Prospective study of incidence of Crohn’s disease in northwest England: no increase since late 1970's. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;6:27-31. |

| 4. | Lindberg E, Jörnerot G. The incidence of Crohn's disease is not decreasing in Sweden. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:495-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Loftus EV, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Crohn's disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1161-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 458] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Björnsson S, Jóhannsson JH. Inflammatory bowel disease in Iceland, 1990-1994: a prospective, nationwide, epidemiological study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:31-38. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kyle J. Crohn's disease in the northeastern and northern Isles of Scotland: an epidemiological review. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:392-399. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Iida M, Yao T, Okada M. Long-term follow-up study of Crohn's disease in Japan. The Research Committee of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 1995;30 Suppl 8:17-19. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Leong RW, Lau JY, Sung JJ. The epidemiology and phenotype of Crohn's disease in the Chinese population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:646-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones J, Logan R, Fear N, Price A, Carpenter L, van Blankenstein M. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD). Gut. 1996;39:690-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 684] [Cited by in RCA: 668] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Blanchard JF, Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Rawsthorne P. Small-area variations and sociodemographic correlates for the incidence of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:328-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jacobsen B, Fallingborg J, Rasmussen H. The incidence of IBD in North Jutland County, Denmark 1978-2002. Gut. 2003;52:A79. |

| 13. | Loftus C G, Loftus EV, Jr . Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen AR, Zinsmeister AR, Melson LJ. Update on incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disesae (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) in Olmsted County Minnesota 2003. DDW. 2003;A278. |

| 14. | Molinié F, Gower-Rousseau C, Yzet T, Merle V, Grandbastien B, Marti R, Lerebours E, Dupas JL, Colombel JF, Salomez JL. Opposite evolution in incidence of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in Northern France (1988-1999). Gut. 2004;53:843-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | LOCKHART-MUMMERY HE, MORSON BC. Crohn's disease (regional enteritis) of the large intestine and its distinction from ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1960;1:87-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lapidus A, Bernell O, Hellers G, Persson PG, Löfberg R. Incidence of Crohn's disease in Stockholm County 1955-1989. Gut. 1997;41:480-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yapp TR, Stenson R, Thomas GA, Lawrie BW, Williams GT, Hawthorne AB. Crohn's disease incidence in Cardiff from 1930: an update for 1991-1995. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:907-911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wolters FL, Russel MG, Stockbrügger RW. Systematic review: has disease outcome in Crohn's disease changed during the last four decades. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:483-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Wajda A. Epidemiology of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in a central Canadian province: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:916-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 493] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rubin GP, Hungin AP, Kelly PJ, Ling J. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology and management in an English general practice population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1553-1559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sweden Statistics. Population statistics for the years 1990-2002. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden 2004; . |

| 22. | Wéden M. Statistics on endoscopy in Stockholm County 1993-2003. 2004;. |

| 23. | Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;170:2-6; discussion 16-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1396] [Cited by in RCA: 1459] [Article Influence: 39.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Breslow N, Day N. Statistical methods in cancer research volume II. Scientific Publications. 1987;32:131-135. |

| 25. | Lakatos L, Mester G, Erdelyi Z, Balogh M, Szipocs I, Kamaras G, Lakatos PL. Striking elevation in incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in a province of western Hungary between 1977-2001. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:404-409. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Armitage E, Drummond HE, Wilson DC, Ghosh S. Increasing incidence of both juvenile-onset Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in Scotland. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1439-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hildebrand H, Finkel Y, Grahnquist L, Lindholm J, Ekbom A, Askling J. Changing pattern of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in northern Stockholm 1990-2001. Gut. 2003;52:1432-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Munkholm P, Langholz E, Nielsen OH, Kreiner S, Binder V. Incidence and prevalence of Crohn's disease in the county of Copenhagen, 1962-87: a sixfold increase in incidence. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:609-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Loftus EV. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504-1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2085] [Cited by in RCA: 2174] [Article Influence: 98.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 30. | Thomas GA, Millar-Jones D, Rhodes J, Roberts GM, Williams GT, Mayberry JF. Incidence of Crohn's disease in Cardiff over 60 years: 1986-1990 an update. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:401-405. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Heresbach D, Alexandre JL, Bretagne JF, Cruchant E, Dabadie A, Dartois-Hoguin M, Girardot PM, Jouanolle H, Kerneis J, Le Verger JC. Crohn's disease in the over-60 age group: a population based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:657-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Piront P, Louis E, Latour P, Plomteux O, Belaiche J. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases in the elderly in the province of Liège. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2002;26:157-161. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Lindberg E, Järnerot G, Huitfeldt B. Smoking in Crohn's disease: effect on localisation and clinical course. Gut. 1992;33:779-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1508-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Farmer M, Petras RE, Hunt LE, Janosky JE, Galandiuk S. The importance of diagnostic accuracy in colonic inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3184-3188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Höög C, Antfolk A, Wirlöf C, Sjöqvist U. [Capsule endoscopy is better than other methods. 66 examinations performed at Sodersjukhuset prove a high diagnostic yield]. Lakartidningen. 2004;101:4102-4106. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy and Crohn's disease. Gut. 2005;54:323-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Wang XL and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Wang J