Published online Jan 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.48

Revised: June 28, 2005

Accepted: July 5, 2005

Published online: January 7, 2006

AIM: To identify the clinical and prognostic features of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) aged 80 years or more.

METHODS: A total of 1310 patients with HCC were included in this study. Ninety-one patients aged 80 years or more at the time of diagnosis of HCC were defined as the extremely elderly group. Two hundred and thirty-four patients aged ≥ 50 years but less than 60 years were regarded as the non-elderly group.

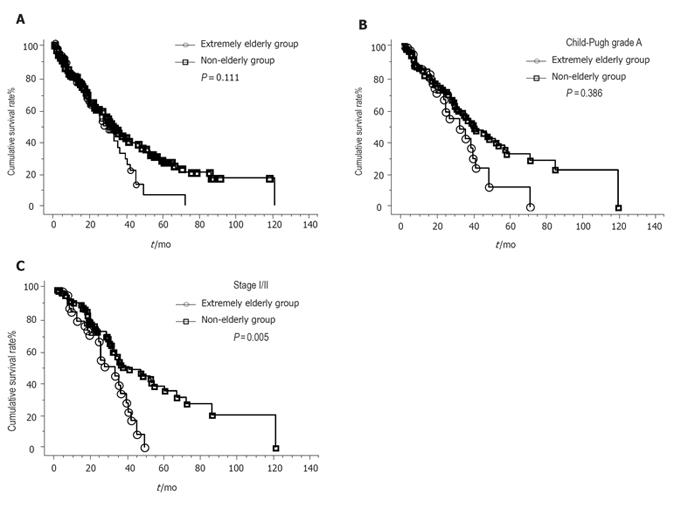

RESULTS: The sex ratio (male to female) was significantly lower in the extremely elderly group (0.90:1) than in the non-elderly group (3.9:1, P < 0.001). The positive rate for HBsAg was significantly lower in the extremely elderly group and the proportion of patients negative for HBsAg and HCVAb obviously increased in the extremely elderly group (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in the following parameters: diameter and number of tumors, Child-Pugh grading, tumor staging, presence of portal thrombosis or ascites, and positive rate for HCVAb. Extremely elderly patients did not often receive surgical treatment (P < 0.001) and they were more likely to receive conservative treatment (P < 0.01). There were no significant differences in survival curves based on the Kaplan-Meier methods in comparison with the overall patients between the two groups. However, the survival curves were significantly worse in the extremely elderly patients with stage I/II, stage I/II and Child-Pugh grade A cirrhosis in comparison with the non-elderly group. The causes of death did not differ among the patients, and most cases died of liver-related diseases even in the extremely elderly patients.

CONCLUSION: In the patients with good liver functions and good performance status, aggressive treatment for HCC might improve the survival rate, even in extremely elderly patients.

- Citation: Tsukioka G, Kakizaki S, Sohara N, Sato K, Takagi H, Arai H, Abe T, Toyoda M, Katakai K, Kojima A, Yamazaki Y, Otsuka T, Matsuzaki Y, Makita F, Kanda D, Horiuchi K, Hamada T, Kaneko M, Suzuki H, Mori M. Hepatocellular carcinoma in extremely elderly patients: An analysis of clinical characteristics, prognosis and patient survival. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(1): 48-53

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i1/48.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.48

With the arrival of the aging society, an increasing number of elderly patients with cancer is predicted in the future. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers and the age distribution of HCC patients has steadily increased because of the improved management of chronic liver diseases[1-5]. As a result, we sometimes encounter patients with HCC aged 80 years or more. However, the clinical characteristics and the long-term prognosis of these patients still remain obscure because they often have concomitant diseases and therefore long-term follow-up for such patients remains difficult. In recent studies, “the elderly” have usually been defined as to be at the ages of 60, 65, or 70 years and above[1-4]. The average life expectancy of Japanese males is 78.36 years, while that of females is 85.33 years[6]. With the increase in the average lifetime, the age at which a person is considered elderly is rising. Clarifying the optimal treatment strategy for extremely elderly patients with HCC has thus become an urgent necessity. However, to our knowledge, there have been so far few reports evaluating extremely elderly patients with HCC aged 80 years or more[5]. Hence, in this study, we aimed to clarify the age-specific clinical characteristics of HCC, and to evaluate the survival and characteristics of extremely elderly patients. We, therefore, undertook a retrospective study of 91 extremely elderly patients with HCC aged 80 years or more in comparison to the non-elderly patients from 1 310 consecutive HCC patients.

A total of 1 310 consecutive patients were enrolled in this study. The patients were newly diagnosed with HCC and observed from January 1992 to December 2003 at the Department of Medicine and Molecular Science, Gunma University Graduate School of Medicine and nine affiliated hospitals, namely, Maebashi Red Cross Hospital, Isesaki Municipal Hospital, Kiryu Kousei General Hospital, Tone Chuo Hospital, National Nishigunma Hospital, Saiseikai Maebashi Hospital, Public Tomioka General Hospital, Fuji Heavy Industries Ltd, Health Insurance Society General Ota Hospital, and Shimada Memorial Hospital. A diagnosis of HCC was confirmed histopathologically or clinicopathologically from biopsy specimens or combined examinations of ultrasonography, computed tomography, and selective angiography. For each patient, the following data were recorded: age, sex, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis C virus antibody (HCVAb), biochemical analysis (total bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, platelet count, and ICG R15), serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist II (PIVKA-II), diameter and number of tumors, Child-Pugh grading, tumor staging, presence of portal thrombosis or ascites, initial therapy, and survival. The AFP level was divided into two categories: 20 μg/L or less, and more than 20 μg/L. PIVKA-II level was also divided into two categories: < 40 and ≥ 40 AU/L. The diameter of the largest tumor was measured in its greatest dimension if the patient had two or more tumors. The number of HCCs was divided into two groups: solitary and non-solitary tumors. Portal thrombosis was defined as a protrusion of the tumor into the first and/or second branch, or into the main trunk of the portal vein. The presence of concomitant disease with a strong impact on the prognosis (e.g., malignant neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease) was recorded. The types of initial treatment for HCC were categorized into five categories: (1) transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) or transcatheter arterial infusion (TAI); (2) percutaneous injection or ablation [percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), microwave ablation (MA), or radiofrequency ablation (RFA)]; (3) surgical resection, including liver transplantation; (4) systemic or reservoir chemotherapy; and (5) supportive care. According to their age at the initial diagnosis, the patients were categorized into two groups: an extremely elderly group consisting of 91 HCC patients aged ≥ 80 years and a non-elderly group comprising 234 HCC patients aged ≥ 50 years but < 60 years.

Differences in the proportions were evaluated by Fisher’s exact probability test. Differences in the means were evaluated by the Student’s t-test. The survival curves according to the Kaplan-Meier method were compared using the log-rank test. Using Cox’s proportional hazard model, a multivariate analysis was performed to evaluate the prognostic factors. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The age distribution of 1 310 patients with HCC is shown in Table 1. The mean age of the 1 310 patients with HCC was 66.7 ± 9.3 years (range, 20 - 94 years; median, 68 years). There were 91 patients who were older than 80 years, and 234 patients aged ≥ 50 years but less than 60 years. The characteristics of the extremely elderly group and the non-elderly group are summarized in Table 2. The sex ratio, with a comparable male to female ratio was 0.90:1 in the extremely elderly group and 3.9:1 in the non-elderly group, showing that women were more prevalent in the extremely elderly group (P < 0.001). The positive rate for HBsAg was significantly lower in the extremely elderly group (P < 0.001). The proportion of the patients negative for HBsAg and HCVAb markedly increased in the extremely elderly group (P < 0.001). The prothrombin time and platelet count were significantly higher in the extremely elderly group (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively), while ICGR15 was significantly lower in the extremely elderly group (P < 0.001) than in the non-elderly group. There were no statistical differences in the prevalence of HCVAb, total bilirubin, albumin, AFP, PIVKAII, diameter and number of tumors, Child-Pugh grading, tumor stage, and presence of portal thrombosis or ascites. Table 3 shows the type of initial treatment. None of the patients underwent a surgical resection in the extremely elderly group. The incidence of TAE or TAI, the percutaneous injection or ablation and chemotherapy were similar in both groups. Extremely elderly patients with HCC were more likely to receive conservative treatment than non-elderly patients (P < 0.01). The performance status (PS) of the patients who received treatment for HCC in the extremely elderly group ranged from PS0 to PS1.

| Age (yr) | Number of HCC patients |

| < 30 | 3 |

| 30-40 | 4 |

| 40-50 | 41 |

| 50-60 | 234 |

| 60-70 | 485 |

| 70-80 | 452 |

| 80< | 90 |

| Tatol | 1310 |

| Extremely elderly | Non-elderly | P-value | |

| (80 yr or more) | (50-60 yr old) | ||

| Sex (M/F) | 43/48 | 186/48 | P < 0.001 |

| Mean age (range) | 82.3 ± 2.7 (80-94) | 55.3 ± 2.9 (50-59) | P < 0.001 |

| HBsAg (+/-) | 3/88 | 36/198 | P < 0.001 |

| HCV (+/-) | 67/24 | 182/52 | NS |

| non B, nonC/B or C | 21/70 | 16/218 | P < 0.001 |

| Diameter of HCC (mm) | 39.5± 24.3 | 36.8± 27.0 | NS |

| Number of HCC (1/2 or more) | 47/44 | 110/124 | NS |

| Child-Pugh grading (A/B/C/uk) | 62/22/3/4 | 144/67/18/6 | NS |

| Stage (I/II/III/IVA/IVB/uk) | 11/37/25/11/3/4 | 44/85/53/36/10/5 | NS |

| Portal thrombus (-/+) | 77/14 | 189/45 | NS |

| Ascites (-/+) | 69/22 | 191/43 | NS |

| T-Bil (μmol/L) | 1.23 ± 1.29 | 1.5± 1.82 | NS |

| Alb (g/dL) | 3.55 ± 0.53 | 3.58 ± 0.6 | NS |

| PT(%) | 83.3 ± 15.9 | 73.6 ± 18.4 | P < 0.001 |

| Plt (x104/μL) | 13.5 ± 7.7 | 10.7 ± 5.8 | P < 0.001 |

| ICGR15(%) | 22.6 ± 11.8 | 31.5 ± 18.7 | P < 0.001 |

| AFP (-/+/uk) | 33/53/5 | 75/150/9 | NS |

| PIVKA II (-/+/uk) | 35/51/5 | 116/109/9 | NS |

| Treatment | Extremely elderly | Non-elderly | P-value |

| (80 yr or more) | (50-60 yr old) | ||

| TAE or TAI | 59 | 128 | NS |

| PEI or RFA or MA | 18 | 62 | NS |

| Surgery (liver trans- plantation) | 0 | 28(3) | P < 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | 2 | 7 | NS |

| Supportive care | 12 | 9 | P < 0.001 |

Figure 1A shows the cumulative survival curves of the extremely elderly group and the non-elderly group. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 75.5%, 32.1%, and 6.4%, respectively, for the extremely elderly group and 79.3%, 43.8%, and 26.5%, respectively, for the non-elderly group. The difference in the survival rates between the two groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.114). Figure 1B shows the cumulative survival curves of the patients with Child-Pugh grade A in the two groups. Although the survival tended to be worse in the extremely elderly patients, it did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.111). There were also no significant differences in survival curves regarding the ChildPugh grade B/C patients (P = 0.386). Due to the small number of patients with stage I tumors in the extremely elderly group, we compared the patients with stage I/II tumors between both groups. Figure 1C shows the cumulative survival curves of the stage I/II patients in both groups. The survival curves were significantly worse in the extremely elderly patients with stage I tumors in the extremely elderly group, we compared the patients with stage I/II tumors between both groups. Figure 1C shows the cumulative survival curves of the stage I/II patients for both groups. The survival curves were significantly worse in the extremely elderly patients with stage I/II tumors (P = 0.005). However, there were no significant differences in survival curves regarding stage III/IV (P = 0.479) or stage IV (P = 0.794) disease. In stage I/II and Child-Pugh grade A patients, the survival curves were significantly worse in the extremely elderly patients (P = 0.005). Survivals adjusted for the etiology of liver disease were also calculated. No significant differences were observed in the survival curves regarding HCV-related disease between the extremely elderly and non-elderly groups (P = 0.142). There were also no significant differences in the survival curves of the patients negative for HBsAg and HCVAb between the two groups (P = 0.447). Due to the small number of patients positive for HBsAg in the extremely elderly group, we could not compare those patients between both groups.

To evaluate the prognostic factors for the extremely elderly HCC patients and non-elderly patients, we performed a multivariate analysis using Cox’s proportional hazard model, which showed that the Child-Pugh grading (P < 0.05), tumor staging (P < 0.01), albumin (P < 0.01), and platelet count (P < 0.05) were prognostic factors for extremely elderly patients with HCC. The Child-Pugh grading (P < 0.05), tumor staging (P < 0.05), and diameter of tumors (P < 0.01) were found to be prognostic factors for the non-elderly patients with HCC. The age, sex, HBsAg, HCVAb, total bilirubin, prothrombin time, number of tumors, and presence of portal thrombosis or ascites were not found to be prognostic factors, based on Cox’s proportional hazard model. In the overall patients with HCC, the Child-Pugh grading (P < 0.05), tumor staging (P < 0.05) and diameter of tumors (P < 0.01) were found to be prognostic factors. The age was not found to be associated with the prognosis of the overall patients with HCC.

Of the 91 patients aged ≥ 80 years, 55 (60.4%) patients died during the observation period Table 4. The causes of death among the 55 patients were HCC-related or hepatic failure in 44 patients (80.0%), gastrointestinal bleeding, including the rupture of esophageal varices in 4 patients (7.3%), and other diseases not related to HCC or liver cirrhosis in 7 patients (12.7%), such as pneumonia, renal failure and brain bleeding. In the non-elderly group, 123 (52.6%) patients died during the observation period. The causes of death among the 123 patients were HCC-related or hepatic failure in 102 patients (82.9%), gastrointestinal bleeding, including rupture of esophageal varices in six patients (5.0%), and other diseases not related to HCC or liver cirrhosis in nine (7.3%) and no records in six patients (5.0%).

| Cause of death | Extremely elderly(80 yr or more) | Non-elderly(50-60 yr old) | P-value |

| HCC | 27 | 77 | NS |

| Hepatic failure | 17 | 25 | |

| Gastrointestinal- Bleeding | 4 | 6 | |

| Others | 7 | 9 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 6 |

Of the 91 patients, 71 (78.0%) patients had concomitant diseases with liver disease in the extremely elderly group. As shown in Table 5, a variety of concomitant diseases were observed in the extremely elderly patients . “Others” in malignant neoplasms included: one ureteral carcinoma, one skin cancer, and one malignant lymphoma. “Other diseases” included: three benign prostatic hypertrophy, one idiopathic thrombocytopenia, one lichen planus, one ovarian cyst, one adrenal adenoma, and six others. On the other hand, 89 of 234 patients (38.0%) had concomitant diseases with liver disease in the non-elderly group. The ratio of patients having concomitant diseases was significantly higher in the extremely elderly group (P < 0.001).

| Concominant disease | Extremely elderly (80 yr or more) | Non-elderly (50-60 yr old) | |

| Malignant neoplasm | Gastric cancer | 2 | 2 |

| Colon cancer | 3 | 4 | |

| Prostatic cancer | 2 | 0 | |

| Others | 3 | 1 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | Ischemic heart disease | 9 | 3 |

| Hypertension | 36 | 32 | |

| Arrhythmia | 7 | 2 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 | 0 | |

| Valvular heart disease | 2 | 0 | |

| Aortic aneurysma | 2 | 0 | |

| Respiratory disease | Chronic bronchitis | 3 | 0 |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 2 | 1 | |

| Pneumonia | 2 | 0 | |

| Others | 3 | 1 | |

| Gastrointestinal disease | Gall stone | 4 | 3 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 1 | 4 | |

| Peptic ulcer | 2 | 5 | |

| Reflux esophagitis | 3 | 1 | |

| Endocrinal disease | Diabetes mellitus | 23 | 47 |

| Gout | 2 | 6 | |

| Others | 0 | 2 | |

| Neurological and cerebrovascular | Cerebral infarction or hemorrhage | 7 | 2 |

| Dimentia | 3 | 0 | |

| others | 0 | 2 | |

| Renal disease | Chronic renal failure or nephritis | 3 | 2 |

| Other disease | 13 | 5 | |

| No concominant disease | 20 | 145 |

Although the survival of the patients with an early stage and a good liver function was better in the non-elderly group, we could not find any significant difference in overall survival curves or causes of death between the extremely elderly and non-elderly groups with HCC. Even though the extremely elderly patients had various concomitant diseases, most of the patients demonstrating HCC died from HCC-related causes. As a result, HCC was a life-limiting factor even though the patients were extremely elder. In Japan, based on data from 2003[6], the average life expectancies at birth are 78.36 years for males and 85.33 years for females. In addition, an 80-year-old male has an average life expectancy of 8.26 years, while a female aged 80 years can expect to live another 11.04 years[6]. The 5-year survival rate in the extremely elderly group with HCC was only 6.4% in this study. We, therefore, have to treat HCC even though such patients are over 80 years of age and have concomitant diseases.

Dohmen et al.[5] analyzed 36 patients aged ≥ 80 years and concluded that the survival rates are not significantly different from the non-elderly group, and that the advanced stage of HCC, not an advanced age, has the greatest influence on the survival rate in extremely elderly patients[5]. Hoshida et al.[8] evaluated 135 patients with chronic liver disease aged ≥ 80 years and found that most patients (63.5%) would die of diseases other than liver diseases, such as pneumonia, especially in the non-cirrhosis group. It is reasonable that the extremely elderly patients without HCC die of diseases other than liver diseases. However, in their study, 18 patients with HCC at the start of observations had a poor prognosis.

Although there was no difference in the Child-Pugh grading, the extremely elderly group had good liver function as indicated by the prothrombin time or ICGR15 level. We speculated that patients with a poor liver function might die of liver failure and will not be able to live until 80 years of age when complicated with HCC. Otherwise, not only the liver function, but also other genetic or environmental factors may contribute to the development of HCC in extremely elderly patients. In this study, extremely elderly patients with HCC had a relatively good PS. The 10 hospitals included in this study are core hospitals for each area. The patients with a poor PS or poor liver function might have been excluded by the primary physician for aggressive treatment of HCC and thus might not have been introduced to these 10 hospitals.

Females were more prevalent in the extremely elderly group (P < 0.001). The proportion of females in the general population is known to gradually increase with increasing age[6]. Males are usually dominant in non-elderly patients with HCC and their prognosis of HCC is quite poor. We speculated that males with HCC might die of liver-related diseases before 80 years of age. However, we could not determine the reason why the female ratio significantly increased in the extremely elderly group of HCC. Previous studies reported that HBV-associated HCC is common in younger patients in Japan[11-13]. Our results were compatible with our expectation because only 3.3% of the HBV-associated HCC was identified in the extremely elderly group in contrast to 15.3% in the non-elderly group (P < 0.001). The ratio of non B and non C hepatitis patients significantly increased in the extremely elderly group. Other factors except for hepatitis virus infection such as alcohol or genetic disturbance may thus contribute to the development of HCC in the extremely elderly group.

Regarding the initial treatment, Collier et al.[10] reported in 1994 that elderly patients (≥ 65 years) with HCC are more likely to receive conservative treatment than younger patients (< 65 years), despite a similar disease stage. Conversely, Poon et al.[3] concluded that a hepatic resection and TAE for HCC in elderly patients (≥ 70 years) are well tolerated and show an improved survival rate. Percutaneous localized therapies or TAE were similarly performed in both the extremely elderly and non-elderly groups in this study and there were no obvious differences regarding adverse effects. However, no surgical resections were performed in the extremely elderly group. The oldest patient receiving a surgical resection as the initial treatment among these 1 310 patients was 77 years. The extremely elderly patients with HCC were more likely to receive conservative treatment than the non-elderly patients. Non-invasive treatments may have been selected due to the patient age or quality of life. Indeed, post-operative complications, such as pneumonia, show an incremental risk with age[14]. The elderly patients are more liable to succumb to post-operative organ failure and complications, especially infections[14]. The PS and physiological age are therefore considered to be more important than the chronological age in elderly patients with HCC.

In conclusion, there is no statistical difference in the overall survival rate between the extremely elderly and non-elderly groups after the diagnosis of HCC. HCC is considered to be a life-limiting factor even in extremely elderly patients. Therefore, in patients with good liver functions and good PS, aggressive treatment of HCC might improve the survival rate, even in extremely elderly patients.

| 1. | Yanaga K, Kanematsu T, Takenaka K, Matsumata T, Yoshida Y, Sugimachi K. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients. Am J Surg. 1988;155:238-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nomura F, Ohnishi K, Honda M, Satomura Y, Nakai T, Okuda K. Clinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly: a study of 91 patients older than 70 years. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:690-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Ngan H, Ng IO, Wong J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly: results of surgical and nonsurgical management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2460-2466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hazama H, Omagari K, Matsuo I, Masuda J, Ohba K, Sakimura K, Kinoshita H, Isomoto H, Murase K, Kohno S. Clinical features and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in eight patients older than eighty years of age. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1692-1696. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Dohmen K, Shirahama M, Shigematsu H, Irie K, Ishibashi H. Optimal treatment strategy for elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:859-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Health and Welfare Statistics Association. Life expectancy. J Health Welfare Stat. 2004;51:67-68. |

| 7. | Dohmen K, Shigematsu H, Irie K, Ishibashi H. Trends in clinical characteristics, treatment and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1872-1877. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Arbaje YM, Carbone PP. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the very elderly: to treat or not to treat. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1994;22:84-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hoshida Y, Ikeda K, Kobayashi M, Suzuki Y, Tsubota A, Saitoh S, Arase Y, Kobayashi M, Murashima N, Chayama K. Chronic liver disease in the extremely elderly of 80 years or more: clinical characteristics, prognosis and patient survival analysis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:860-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Namieno T, Kawata A, Sato N, Kondo Y, Uchino J. Age-related, different clinicopathologic features of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Ann Surg. 1995;221:308-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kato Y, Nakata K, Omagari K, Furukawa R, Kusumoto Y, Mori I, Tajima H, Tanioka H, Yano M, Nagataki S. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis in Japan. Analysis of infectious hepatitis viruses. Cancer. 1994;74:2234-2238. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Dohmen K, Shigematsu H, Irie K, Ishibashi H. Comparison of the clinical characteristics among hepatocellular carcinoma of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and non-B non-C patients. Hepatogastroenterology ; 50: 2022-. 2027;. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Collier JD, Curless R, Bassendine MF, James OF. Clinical features and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in Britain in relation to age. Age Ageing. 1994;23:22-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Koperna T, Kisser M, Schulz F. Hepatic resection in the elderly. World J Surg. 1998;22:406-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Kumar M and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Wu M