These 103 splenic abnormalities were accessory spleen in 5 patients, true cysts in 22 and pseudocysts in 9 patients, splenic calcification and Gamna-Gandy bodies in 10 patients, cavernous hemangiomas in 15 patients, abscesses is 8 patients, lymphomas in 8 patients, metastatic tumors in 5 patients, splenic infarctions in 10 patients, hematomas and rupture in 11 patients.

Diseases of the spleen

Congenital abnormalities Some congenital anomalies of the spleen are common, such as splenic lobulation and accessory spleen, while other conditions are rare, such as wandering spleen[3] and polysplenia[4]. Failure of fusion of splenic tissue results in the formation of an accessory spleen. US appearances usually present as a homogenous, less than 4 cm round contour near the hilum and an echogenicity identical to that of adjacent spleen. Pathologic processes affecting the spleen also affect the accessory spleen, indicating that they have the same developmental origin (Figure 1). An intrapancreatic or intrahepatic accessory spleen is a homogenous mass in the parenchyma of the pancreas or liver that may mimic a neoplastic lesion[5,6]. As it poses no danger, accurate diagnosis is necessary to avoid unnecessary treatment. The diagnosis of ectopic splenic tissue is best made by technetium-99m colloid scintigraphy[7].

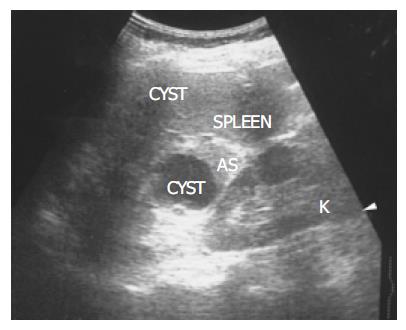

Figure 1 There is a homogenous, round contour near the hilum, identified as an accessory spleen (AS) in a 62-year-old female.

One anechoic cyst is noted within the accessory spleen. The pathologic process affecting the spleen (small cyst) also affects the accessory spleen (large cyst).

Splenomegaly and portal hypertension As the spleen is an irregularly shaped organ, no completely satisfactory technique has been developed to measure the volume accurately. Estimating the volume with the formula 0.524 × W × T × (ML + CCL)/2 (where ML = maximum length, W = width, T = thickness, and CCL = craniocaudal length) provides better overall accuracy[8]. The differential diagnosis for splenomegaly includes infection, portal hypertension, storage disorders, blood dyscrasias, and neoplasm. Mild splenomegaly can be seen in infections and portal hypertension. Moderate splenomegaly suggests leukemia, lymphoma, or infectious mononucleosis. Massive splenomegaly is seen in myelofibrosis or chronic myeloid leukemia. The presence of portosystemic collateral vessels, ascites, and cirrhosis of the liver indicates portal hypertension[9]. The presence of space-occupying lesions within an enlarged spleen suggests lymphoma, metastases, or abscesses.

Splenic calcification and Gamna-Gandy bodies Foci of hemosiderin and calcium deposits in the splenic parenchyma secondary to intraparenchymal hemorrhage are called Gamna-Gandy bodies (Figure 2). They are commonly seen in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension and are also found in patients with splenic vein thrombosis, hemolytic anemia, hemochromatosis, or trauma[10]. Echogenic foci with acoustic shadowing indicating calcification are found in chronic granulomatous infections such as tuberculosis, harmatomas, sickle cell disease[11] and trauma.

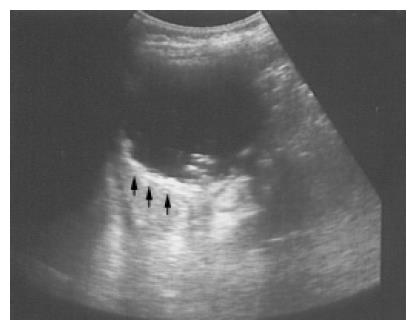

Figure 2 Multiple tiny calcified spots involving almost the entire spleen are found in a 58-year-old female with liver cirrhosis, called Gamna-Gandy bodies.

Splenic cysts Splenic cysts are rarely seen, but they are still probably the commonest splenic lesions. They are much less common than those arising in the kidney, liver, or ovary. They can be true cysts, pseudocysts, or hydatid cysts. The true cyst, also known as an epidermoid cyst, is defined by the presence of an inner endothelial lining. Pseudocysts that lack such a lining are usually secondary to old trauma, a resolved infection, or infarction. Hydatid cysts are formed by the larval stage of the dog tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus. Simple cysts pose less diagnostic problems if they have the classic ultrasonic features of being anechoic and thin-walled with posterior echo enhancement. Splenic cysts usually are located completely within the spleen, thus differing from hepatic or renal cysts which may have an exophytic component. Infection or hemorrhage may cause debris and echogenic contents within thick-walled pseudocysts (Figure 3). Brightly foci with acoustic shadow due to calcification within the wall is also a correlative US feature to pseudocysts. A rare complication of pancreatic pseudocyst may be erosion into the adjacent spleen, where it mimics a huge simple splenic cyst (Figure 4). Rupture of an intrasplenic pancreatic pseudocyst can result in massive hemoperitoneum. Miele stated that internal septa are more frequent in true cysts while parietal calcifications are typical of pseudocysts[12]. However, the final diagnosis is made histologically.

Figure 3 A pseudocyst cyst of the spleen after trauma reveals debris or echogenic contents within the thick wall (arrows) in a 60-year-old female.

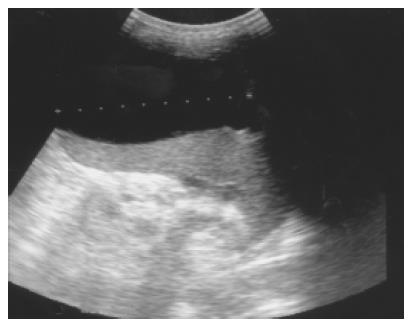

Figure 4 Pancreatic pseudocyst eroding into the adjacent spleen and mimicking a huge splenic simple cyst was noted after an episode of acute alcoholic pancreatitis in a 32-year-old male patient.

Splenic abscess A splenic abscess is a collection of pus, most commonly caused by hematogenous spread of infection from elsewhere. Intravenous drug abusers are predominantly affected. Other causes include penetrating wounds or complications of a hematoma resulting from infarction or trauma. A pyogenic abscess is typically hypoechoic and often has thick, irregular walls. Other findings include gas, progressive enlargement of the lesion, subcapsular extension and collections of extracapsular fluid[13]. If gas has formed within the abscess, hyperechogenicity with distal dirty shadowing can be seen. Through transmission indicates the cystic nature of an abscess even when it contains echogenic material. Color Doppler examination may reveal hypervascularity in the thick wall. The clinical triad suggestive of splenic abscess consists of fever, left upper quadrant pain, and leukocytosis. The typical triad was seen in 44% of patients in one series of 34 cases[14]. Although splenic abscess is rare, there is a high mortality if diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Percutaneous drainage of a single abscess and splenectomy for multiple abscesses are recommended. Fine-needle aspiration is useful when an abscess is suspected, as this may confirm the diagnosis as well allowing culture of the pathogen. In the series noted above, multiple or gas-containing abscesses had a poor prognosis[14].

Hemangioma A hemangioma is characterized by a proliferation of blood-filled spaces lined and separated by endothelium. Cavernous hemangiomas are the most common solid benign lesion seen in the spleen and are found incidentally. The US appearance varies widely from a predominately solid to mixed to a pure cystic lesion. Hemangiomas usually have a periphery and a hypoechoic center with a through transmission character similar to cavernous hemangioma of the liver. Color Doppler may show blood flow within the solid portions. Atypical features are commoner in larger lesions and include heterogeneous echogenicity with hypoechoic areas due to necrosis, hemorrhage, and thrombosis (Figure 5). Rarely, hemangiomas may be large or multiple and can involve the whole spleen (Figure 6). The most frequent complications are rupture and bleeding. Although up to 14% of patients in autopsy series have been reported to have splenic hemangiomas[2], but they are less frequently identified on imaging.

Figure 5 An atypical hemangioma can have mixed echogenicity with a dominant cystic portion.

Mild through transmission points to the cystic nature of the hemangioma.

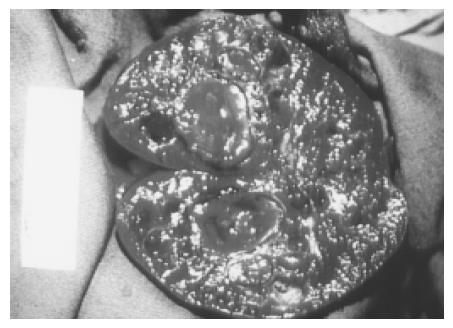

Figure 6 Large and multiple hemangiomas occupy the entire spleen.

The hypoechoic areas shown in Figure 5 are filled with blood clots and thrombosis. The 48-year-old male received splenectomy due to LUQ pain caused by venous thrombosis in spleen.

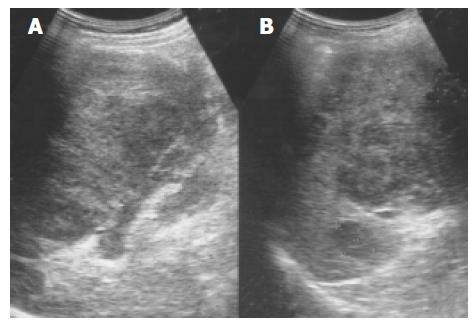

Lymphoma Primary malignant tumors of the spleen are uncommon, with primary lymphoma and angiosarcoma being the most frequently reported. Splenomegaly is a frequent finding in lymphoma, but a normal sized spleen does not exclude the diagnosis[15]. The US patterns correspond to the three macroscopic morphologies: (1) infiltrative and diffuse, (2) miliary and nodular, and (3) focal and cyst-like (Figure 7)[16]. In cyst-like lymphoma, the appearance of a distinct boundary is an important clue in distinguishing lymphoma from cyst[17]. Indistinct boundary echo pattern indicated splenic lymphomas. Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma can not be distinguished by the US appearance.

Figure 7 An enlarged spleen (A) demonstrates a diffusely coarse echotexture with several mixed echoic lesions (B) in a 58-year-old male patient.

Metastatic tumor Metastatic involvement of the spleen is very uncommon, usually seen in patients with widespread, terminal malignant disease. The most frequent metastases arise from lymphoma and melanoma, followed by carcinoma of the ovary, breast, lung, and stomach in decreasing order of frequency[2]. Target lesions with a hypoechoic halo suggest metastasis (Figure 8). This appearance is said to be a sign of aggressive behavior, but other authors have postulated that it is due to necrosis or hemorrhage. Miliary tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteria, and pneumocystis carinii, especially in immunocompromised patients, can also result in multiple hypoechoic focal lesions[18]. These should be differentiated from splenic metastases.

Figure 8 Splenic metastasis from a lung carcinoma in a 68-year-old male is seen as a hypoechoic mass with a target sign.

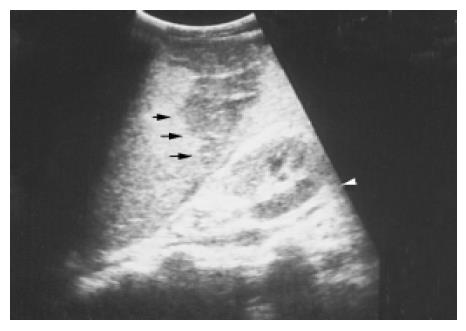

Splenic infarction Infarction can result from either occlusion of the splenic artery or venous thrombosis in the splenic sinusoids. Splenic infarction is typically seen in patients prone to embolic phenomena or, more recently, as a complication of transcatheter arterial embolization of a hepatoma. In splenic vein thrombosis, the entire spleen may be involved, resulting in massive splenomegaly. US typically show a peripheral, wedge-shaped region of hypoechogenicity (Figure 9). Color Doppler imaging may show a lack of perfusion; however, the presence of flow within a lesion does not exclude the diagnosis because the embolus may subsequently lyse. Splenic infarcts may initially be large and then become small and echogenic as fibrosis occurs.

Figure 9 A peripheral wedge-shaped hypoechoic region (arrows) was noted at the upper pole of spleen from an infarction after transcatheter arterial embolization in a 45-year-old male with hepatoma.

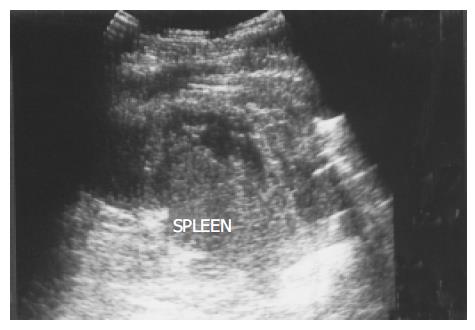

Hematoma and rupture The spleen, liver, and kidney are the three intraperitoneal organs most commonly injured by blunt trauma. If the capsule of the injured spleen remains intact, an intraparenchymal or subcapsular hematoma (Figure 10) may result. Echogenicity of a hematoma depends on the stage at which the scan was performed. Fresh blood is liquid and initially echo-free but over the course of several days becomes more echogenic and thus more difficult to identify. Free fluid in the left upper quadrant is strongly suggestive of splenic injury, which must be excluded in such a case[19]. Less frequently, a splenic laceration or rupture is identified as a blood-filled cleft with capsular rupture. (Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 10 A subcapsular crescent-shaped hypoechoic lesion is noted at the upper pole of spleen.

Figure 11 Several linear hypoechoic foci and a subcapsular fluid accumulation are noted in a spleen.

Loss of the normal architecture was seen after a traffic accident in a 38-year-old male.

Figure 12 A splenic laceration and rupture (in Figure 11) is identified as a blood-filled cleft (lower arrow) and capsular rupture (upper arrow) on contrast CT.

Biopsy procedures In many cases, pathologic confirmation is necessary to provide a definitive diagnosis. The traditional dry cytologic aspiration is relatively safe but provides only a small sample. Siniluoto et al[20] reported false-negative results for malignancy is about 31% of biopsies using a 22-gauge fine needle aspiration technique. Core-needle biopsies with and 18 or 20-gauge cutting-biopsy needle may increase the diagnostic accuracy by obtaining a sufficiently large specimen. And Katsumi et al[21] reported the safety of this procedure in four cases. All procedures should be carefully planned in advance to avoid hitting the intestine, pancreas, kidneys or pleura as the needle is advanced. Color Doppler imaging helps avoid passing the needle through a large vessel. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration may be used in if the lesion is adjacent to the hilum or too small for a CT- or US-guided biopsy. A linear echo endoscope and 22-gauge needles are used to obtain specimens for cytology[22]. To avoid unnecessary morbidity and mortality, laparotomy and splenectomy for pathologic confirmation should be used only when absolutely required.