Published online Jun 14, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i22.3461

Revised: August 28, 2004

Accepted: November 4, 2004

Published online: June 14, 2005

AIM: To evaluate the quality of gastric ulcer healing after different antiulcer treatment by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS).

METHODS: The patients were divided into three groups, and received lansoprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin for 1 wk. Then group A took lansoprazole combined with tepreton for 5 wk, group B took lansoprazole and group C took tepreton for 5 wk. Endoscopy and EUS were performed before and 6 wk after medication.

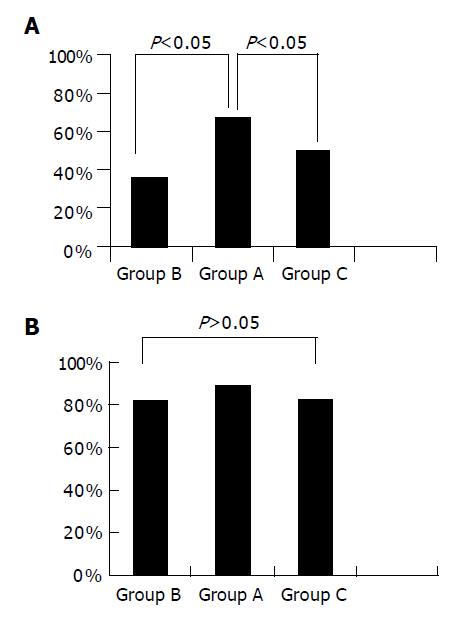

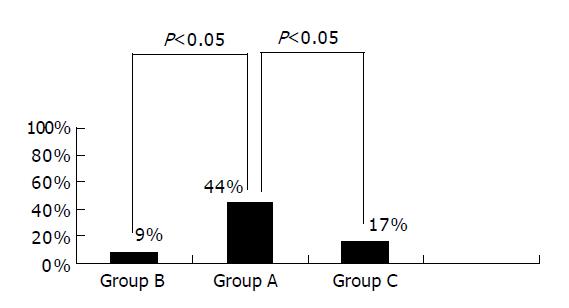

RESULTS: There was no significant difference in cumulative healing rate to S stage between the groups (89%, 82% vs 83%, P>0.05). The rate of white scar formation was significantly higher in group A than in groups B and C (67%, 36%, 50%, P<0.05). The average contraction rates of the width of ulcer crater, length of disrupted muscularis propria layer and hypoechoic area were higher in group A than in groups B and C (0.792±0.090, 0.660±0.105 vs 0.668±0.143, P<0.05). The hypoechoic area disappeared in four cases of group A, one of group B and two of group C. The percentage of hypoechoic area disappearance was higher in group A than in the other two groups (44%, 9% vs 17%, P<0.05). Gastric ulcer healing was better in group A.

CONCLUSION: The combined administration of proton-pump inhibitors and mucosal protective agent can improve gastric ulcer healing.

- Citation: Si JM, Cao Q, Wu JG. Quality of gastric ulcer healing evaluated by endoscopic ultrasonography. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(22): 3461-3464

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i22/3461.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i22.3461

With the introduction of antiulcer agents, the peptic ulcer healing rate has increased considerably, but the high recurrence rate after treatment is a major concern for primary care physicians. Infection with Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) is the main reason; however, ulcer recurrence may be attributed to other factors such as gastric acid rebound and the persistent presence of mucosal aggravating factors. In 1991, Tarnawski et al[1], put forward a new concept of quality of ulcer healing (QOUH). A growing number of reports indicate that low recurrence rate occurs after high QOUH is achieved. Therefore, attentions have been focused on making a good choice of antiulcer agents to promote the QOUH. Although healing of gastric ulcer has been studied radiologically, endoscopically, and by other techniques, these studies were not able to obtain an objective estimate of the transmural histological changes accompanying the healing process within the ulcer[2]. Such changes could only be estimated from superficial changes during ulcer healing. The techniques of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) make it possible to observe the ulcer vertically as the cross-sectional image. The present study was designed to evaluate the quality of gastric ulcer healing in 32 patients by EUS and endoscopy. Quality of gastric ulcer healing could be improved after 6-wk treatment, whether high quality of gastric ulcer healing could be achieved by administration of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) in combination with mucosal protective agent, difference in quality of gastric ulcer healing between using PPIs or mucosal protective agent alone as a maintenance therapy.

Thirty-two patients were enrolled from June 2001 to May 2002. All patients aged 18-70 years had an endoscopic and ultrasonographic diagnosis of deep gastric ulcer (ulcer that completely disrupts the muscularis propria layer[3]) in active stage 1 or 2 (A1 or A2), regardless of gender and status of H pylori infection. Subjects did not take antiulcer agents and all gastrointestine related medications were stopped 3 d prior to study. The patients with major organ diseases (heart, liver, lung, kidney, etc.), malignant ulcer, NSAID-induced ulcer, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, and pregnancy were excluded in the study. The background factors of patients are shown in Table 1.

| Group A | Group B | Group C | |

| Number of cases | 9 | 11 | 12 |

| Gender (M/F) | 2:7 | 3:8 | 4:8 |

| Age (yr) | 43.3±22.4 | 47.1±19.8 | 53.3±20.2 |

| Ulcer location | 3:4:2 | 5:3:3 | 4:5:3 |

| (antrum/angulus/body) | |||

| H pylori (pretreatment) | 8 | 9 | 9 |

| H pylori (after treatment) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| W1 (mm) | 8.43±2.40 | 9.08±2.51 | 9.52±2.34 |

| L1 (mm) | 16.30±3.41 | 14.38±3.29 | 16.19±3.49 |

| A1 (mm) | 402.76±94.89 | 394.85±74.82 | 424.56±65.61 |

Subjects were randomly divided into three groups using the envelope method. All the patients received lansoprazole (takeprone, 30 mg b.i.d.), amoxicillin (1000 mg b.i.d.) and clarithromycin (klacid, 500 mg b.i.d.) for 1 wk as a routine H pylori eradication triple therapy[4]. Then group A took lansoprazole (takeprone, 30 mg q.i.d.) combined with tepreton (selbex, 50 mg t.i.d.) for 5 wk. Group B took lansoprazole (takeprone, 30 mg q.d.) for 5 wk. Group C took tepreton (selbex, 50 mg t.i.d.) for 5 wk.

Endoscopy and EUS were performed immediately before medication and 6 wk after medication. The same physician performed all EUS procedures with no knowledge of the patients’ treatment regimen. The endoscopic equipment used was an Olympus GIF-240 and EUS equipment was a FUJINON SP-701 radial scanning ultrasound endoscopic diagnostic device with a frequency of 12 MHz, air was removed and water was injected to produce the image.

The stages of ulcer were classified according to the method of Sakita and Miwa[5], white scars were classified as S2 while red scars as S1. Layers of the gastric wall were determined by EUS according to the report of Aibe et al[6]. Examination of the depth of open ulcer and ulcer scars by EUS was in accordance with Murakami’s classification[7,8]. Open ulcers consisted of three components: an ulcer crater, a hyperechoic layer at the floor of the crater, and an internal hypoechoic area.

During endoscopic examination before and after treatment, two biopsy specimens were taken with a sterilized biopsy forceps from an area of intact mucosa 1 cm from an ulcer crater or a healed ulcer. One specimen was stained with Giemsa to show H pylori, the other was for rapid urease test to show H pylori infection. Patients were regarded as having H pylori infection if either one of the tests was positive but both tests needed to be negative to rule out H pylori infection.

Endoscopic observation parameters included ulcer location (body/angulus/antrum), cumulative healing rates at S stage (including S1 and S2 stages) and S2 stage. EUS observation parameters include width (W) of ulcer crater before (W1) and 6 wk after medication (W2), length (L) of disrupted muscularis propria layer before (L1) and 6 wk after administration (L2), hypoechoic area (A) of the ulcer base before (A1) and 6 wk after administration (A2), condition of the hypoechoic area disappearance 6 wk after drug administration. The quality of gastric ulcer healing was estimated by the contraction rates of W, L, A and the disappearance rate of hypoechoic area.

Results were expressed as mean±SD. Data were analyzed using Student’s t test and χ2 test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The background factors of the 32 patients are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the three groups.

Figure 1 shows the gastric ulcer healing rates at S2 and S stage. The cumulative healing rate at S2 and S stage was 67% and 89% respectively in group A, 36% and 82% respectively in group B, 50% and 83% respectively in group C. There was no significant difference in the healing rate at S stage among the three groups (P>0.05). However, the rate of white scar formation was significantly higher in group A than in groups B and C (P<0.05). The results indicated that the healing time was not shortened by administration of PPIs in combination with mucosal protective agents. In other words, they could improve the quality of healing by promoting white scar formation rather than by shortening the time of healing.

We observed the width (W) of ulcer craters, length (L) of disrupted muscularis propria layer, and hypoechoic area (A) before and 6 wk after therapy. We calculated the contraction rates of W, L, and A. The average rates were higher in group A than in groups B and C (P<0.05). There was no significant difference between groups B and C (Table 2).

| Group A | Group B | Group C | |

| Contraction rates of W | 0.623±0.067 | 0.537±0.098 | 0.585±0.123 |

| Contraction rates of L | 0.496±0.052 | 0.391±0.073 | 0.407±0.083 |

| Contraction rates of A | 0.792±0.090 | 0.660±0.105 | 0.668±0.143 |

We also observed the conditions of hypoechoic area disappearance 6 wk after drug administration. The hypoechoic area disappeared in four cases of group A, one of group B and two of group C. The percentage of hypoechoic area disappearance was higher in group A than in the other two groups (P<0.05). There was no significant difference between groups B and C (P>0.05) (Figure 2).

In terms of the contraction rates of W, L, and A as well as the condition of hypoechoic area disappearance, the quality of gastric ulcer healing tended to be better in group A, suggesting that administration of PPIs in combination with mucosal protective agents could improve the quality of gastric ulcer healing.

Since the advent of antiulcer agents in clinical practice, the healing rate of peptic ulcer has reached more than 95%. But the high recurrence rate is greatly concerned.

Ulcer recurrence may be attributable to other factors, such as gastric acid rebound, persistent presence of mucosal aggravating factors, and impairment of local protective mechanisms. It has been reported that recurrence is common when gastric ulcers form a red scar with red regenerative epithelium, whereas ulcers that form a white scar with an epithelium similar to the normal surrounding mucosa show a low rate of recurrence[10].

Based on a visual examination, the ulceration process includes three stages, namely stage A (active stage), stage H (healing stage) and stage S (scar stage), the ulcer scars are classified by color as S1 (red) or S2 (white). Histologically, the healing of ulcer is accomplished by filling mucosal defect with epithelial cells and connective tissue to reconstruct mucosa. Epithelial cells at the ulcer margin dedifferentiate and proliferate, supplying cells for re-epithelialization of the mucosal scar surface and reconstruction of glandular structures. Granulation tissue at the ulcer base supplies connective tissue cells to restore the lamina propria and endothelial cells and microvessels for mucosal microvasculature reconstruction. The final outcome of healing reflects a dynamic interaction between “epithelial” component from the ulcer margin and connective tissue component containing microvessels originating from granulation tissue. The ulcer healing process is influenced by gastric acid, pepsin and growth factors such as epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor (TGF alpha) and fibroblast growth factor, etc. It has long been postulated that mucosa in areas of grossly ‘healed’ gastric or duodenal ulcers returns to normal, either spontaneously or after treatment[11]. This assumption is based almost entirely upon visual examination by endoscopy. Histological and ultrastructural studies can examine the deeper mucosa in areas of grossly healed ulcers, the gastric mucosa of grossly ‘healed’ ulcers show re-epithelialization of the mucosal surface, but showed prominent abnormalities present in the subepithelial mucosa including reduced height, marked dilation of gastric glands, poor differentiation and/or degenerative changes in glandular cells, increased connective tissue, and disorganized microvascular network. These abnormalities could interfere with oxygenation, nutrient supply, and mucosal resistance and defense, thus becoming the factors for ulcer recurrence. These observations indicate that the quality of mucosal structural restoration rather than the speed of ulcer healing is the most important factor in determining risk of ulcer recurrence[1,11]. In 1991, Tarnawski et al[1], put forward a new concept of QOUH. Since then, EUS has been used to estimate the ulcer healing process and attentions have been focused on the correlation between QOUH and effective ulcer treatment.

Kimura et al[12], reported that the QOUH can be classified into high, fair and poor quality. High quality healing recognized on EUS is complete disappearance of a low echo mass and subsidence of the wall thickness. They studied 79 patients with gastric ulcer by EUS for a year, found that the incidence of high quality healing was 21.2% (11 of 52 ulcer scars) in the S1 stage group, which remarkably increased up to 70.4% (19 of 27) in the S2 group (P<0.01). The cumulative relapse rate at 12 mo during maintenance therapy with H2 blocker was found to be 4.5% in the group with high quality healing on EUS, 40.9% in the group with fair quality healing, and 75% in the group with poor quality healing. Hence the aim of antiulcer treatment is to promote the QOUH and reduce the recurrence rate. The primary care physicians are looking for a good choice of antiulcer agents to achieve high quality of healing. Caution should be taken for indiscriminate and long-term administration of antiulcer medications.

Most studies based on visual examination (by endoscopy in patients, or the evaluation of ulcer size in experimental studies) have shown the efficacy of new antiulcer drugs on healing of gastric ulcers, but few were based on EUS[13]. We designed the present study to objectively establish a relationship between the efficacy of antiulcer drugs and quality of gastric ulcer healing by EUS and endoscopy.

Taking group A for example, although the cumulative healing rate at S2 stage was 67%, the high quality of gastric ulcer healing was 44%. The grossly ‘healed’ ulcer did not represent true healing completely. EUS may provide a reliable and objective assessment of the quality of gastric ulcer healing.

The routine course of gastric ulcer treatment is 6 wk, but after evaluating the quality of gastric ulcer healing by EUS in 32 patients, we found that administration of drugs for 6 wk was not enough to achieve high quality of gastric ulcer healing (the highest rate was only 44%). An insufficient time period of treatment may be another reason for ulcer recurrence. We need further studies to establish an effective course of gastric ulcer treatment.

After evaluating the quality of gastric ulcer healing by EUS in 32 patients, we also conclude that combined treatment of PPIs with mucosal protective agents gave a desirable result in terms of promoting the quality of gastric ulcer healing. Using PPIs or mucosal protective agent alone as a maintenance therapy for gastric ulcer showed no significant difference after 5 wk. PPIs can inhibit the secretion of gastric acid, defense factors and impair tissue regeneration. The mucosal protective agents such as teprenone can increase phospholipid and glycoprotein macromolecules in gastric mucosa and stimulate gastric mucosal blood circulation and increase prostaglandins in mucosa. They also stimulate secretion of growth factors. Tarnawski et al[14], also found that inhibition of acid secretion significantly accelerates ulcer healing, but acid reducers used alone cannot improve the quality of healing. Both sucralfate and omeprazole treatment can improve the quality of gastric ulcer healing. Stimulating actions of sucralfate on growth factors may be the basis for improving the QOUH. PPIs and mucosal protective agents may be used in maintenance therapy.

| 1. | Tarnawski A, Stachura J, Krause WJ, Douglass TG, Gergely H. Quality of gastric ulcer healing: a new, emerging concept. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13 Suppl 1:S42-S47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Imaizumi H, Koizumi W, Nakai H, Tanabe S, Ohida M, Saigenji K. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on the healing process of peptic ulcers. Nihon Rinsho. 1999;57:167-172. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Okai T, Sawabu N, Songür Y, Motoo Y, Watanabe H. Comparison of lansoprazole and famotidine for gastric ulcer by endoscopic ultrasonography: a preliminary trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20 Suppl 2:S32-S35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Asaka M, Satoh K, Sugano K, Sugiyama T, Takahashi S, Fukuda Y, Ota H, Murakami K, Kimura K, Shimoyama T. Guidelines in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan. Helicobacter. 2001;6:177-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Takemoto T, Sasaki N, Tada M, Yanai H, Okita K. Evaluation of peptic ulcer healing with a highly magnifying endoscope: potential prognostic and therapeutic implications. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13 Suppl 1:S125-S128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Aibe T, Fuji T, Okita K, Takemoto T. A fundamental study of normal layer structure of the gastrointestinal wall visualized by endoscopic ultrasonography. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1986;123:6-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamanaka T, Nakazawa S, Segawa K, Yoshino J. An analysis of the structure of gastric ulcer by endoscopic ultrasonography. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1987;84:187-198. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Murakami T, Suzuki T. Pathology of gastric and duodenal ulcers, 1st edition. Nankodo: Tokyo 1971; 79-102. |

| 9. | Tanaka M, Maruoka A, Chijiiwa Y, Tanaka M, Nawata H. Endoscopic ultrasonographic evaluation of gastric ulcer healing on treatment with proton pump inhibitors versus H2-receptor antagonists. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:1140-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nebiki H, Arakawa T, Higuchi K, Kobayashi K. Quality of ulcer healing influences the relapse of gastric ulcers in humans. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:109-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tarnawski A, Douglass TG, Stachura J, Krause WJ. Quality of gastric ulcer healing: histological and ultrastructural assessment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1991;5 Suppl 1:79-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kimura K, Yoshida Y, Kihira K, Kasano T, Ido K. Endoscopic ultrasonographic (EUS) evaluation of the quality of gastric ulcer healing. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1993;28 Suppl 5:178-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang XS, Li YN. The quality of ulcer healing. Chinese J Internal Medicine. 1995;34:274-276. |

| 14. | Tarnawski A, Santos AM, Hanke S, Stachura J, Douglass TG, Sarfeh IJ. Quality of gastric ulcer healing. Is it influenced by antiulcer drugs? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;208:9-13. |