Published online Jan 7, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i1.94

Revised: May 31, 2004

Accepted: July 17, 2004

Published online: January 7, 2005

AIM: To investigate the clinicopathological factors underlying the ethnic differences of Helicobacter pylori gastritis and cancer.

METHODS: We analyzed clinicopathological parameters of gastric biopsies having H pylori infection that were randomly selected from different ethnic populations including 147 Americans, 149 Japanese, and 181 Koreans.

RESULTS: Males were predominant in Japanese and Korean populations (77.9 and 67.4% respectively) in comparison with Americans (48.3%) (P<0.001). H pylori gastritis in Koreans and Japanese was characterized by the predominant antral involvement. In the antrum, neutrophilic infiltration into the proliferative zone of pit, i.e., acute foveolitis, was more frequent in Koreans (82%) than in Japanese (71%) (P<0.05) and Americans (61%) (P<0.001). Interstitial neutrophilic infiltration, intestinal metaplasia and atrophy were also frequent in Koreans and Japanese. In the body, the prevalence of acute foveolitis was not significantly different among the populations while chronic interstitial inflammation and lymphoid follicles were more pronounced in the body of Americans than in the body of others (P<0.01).

CONCLUSION: The male-, and antrum-predominant H pylori gastritis in Koreans and Japanese is compatible with the pattern of sex and topographical distribution of gastric cancer incidence. Our data suggest that persistent acute foveolitis at the proliferative zone is a crucial step in the gastric carcinogenesis.

-

Citation: Lee I, Lee H, Kim M, Fukumoto M, Sawada S, Jakate S, Gould VE. Ethnic difference of

Helicobacter pylori gastritis: Korean and Japanese gastritis is characterized by male- and antrum-predominant acute foveolitis in comparison with American gastritis. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(1): 94-98 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i1/94.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i1.94

Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection is worldwide. The prevalence of H pylori infection increases with age, but is quite different among the populations[1-4]. In USA, the prevalence is less than 20% at 20 years of age, then increases to approximately 50% at 50 years of age[2]. In Japan, it is also less than 20% under 20 years, but increases rapidly to the plateau of 80% over the age of 40[3]. In Korea, the prevalence rate is the highest; it has already reached 50% at 5 years of age, and 90% in asymptomatic adults over the age of 20[4].

The prevalence of H pylori gastritis tends to correlate with the incidence of gastric cancer[5,6]. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the incidence rate of gastric carcinoma in the United States of America was the lowest in the cited countries in 1993[7]. On the other hand, Korea and Japan are among the countries having the highest gastric cancer rates in the world[8,9].

The epidemiological data suggest that H pylori gastritis is associated with gastric carcinogenesis[5,6]. However, the considerable ethnic difference in the incidence of gastric cancer may not be explained by the difference in the infection rate alone[10]. Unknown factors of host, organism, and environment may be involved in the pathogenesis. These factors may be independent of the development and progression of gastritis or may have an influence on the intensity and/or the ‘quality’ of gastritis. Factors of the latter category may be found by comparative analysis of H pylori gastritis among the populations with a different gastric cancer incidence. They may provide an insight into the carcinogenetic pathway and premalignant conditions of gastric cancer, which have been eagerly sought for[11].

The pathobiology of H pylori gastritis is peculiar in many aspects. H pylori gastritis is characterized by severe, acute and chronic inflammation, which would last for decades if not treated properly[12]. Such a persistent inflammation, especially the acute inflammation (neutrophilic infiltration), is exceptional in other organs or biological systems. Persistent neutrophilic infiltration would have serious biological implications. Activated neutrophils generate reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, which are mutagenic and carcinogenic[13,14]. The persistent neutrophilic infiltration in chronic H pylori gastritis has been regarded to denote the ‘activity’ of gastritis[12].

The neutrophilic infiltration involves epithelium as well as lamina propria[15-17]. Characteristically, epithelial neutrophilic infiltration, i.e., acute foveolitis, specifically localizes to the proliferative zone of the mucosa[17-19], in which the gastric epithelium proliferates exclusively[20]. Acute foveolitis is present throughout the longstanding course of H pylori gastritis[17]. The targeted neutrophilic infiltration would induce extensive genomic damage among the proliferating cells, which may exhibit “the malgun(clear) cell change” that is characterized by clear, enlarged nuclei and cytoplasm[18,19].

In this study, we analyzed various pathologic parameters of H pylori gastritis of the subjects from USA, Japan and Korea. Pathological parameters regarding the inflammatory components and associated mucosal changes were defined and graded under objective criteria. Our results show that H pylori gastritis in Koreans and Japanese is characterized by male-, antrum-dominant acute gastritis whereas Americans have pangastritis involving the body and antrum together. The pathobiological implications in relation to gastric carcinogenesis were discussed.

Gastric biopsies having H pylori infection were selected randomly from the surgical pathology files of Rush-Presbyterian St. Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA, Nagahama City Hospital, Shiga, Japan, and Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. The selected populations included 147 Americans (71 men and 76 women, age 57.4±17.9 years), 149 Japanese (116 men and 33 women, age 48.5±13.5 years) and 181 Koreans (122 men and 59 women, age 50.9±14.9 years). All cases were confirmed to have H pylori-like organisms histopathologically. Cases having ulcer or cancer were excluded. The American population was composed of individuals from various ethnic backgrounds including Caucacians and Latin Americans. They resided in large cities, and underwent gastroscopic examination for either mild epigastric symptoms or routine screening. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committees.

Biopsies were reviewed according to the Sydney system[12] with additional definitions in detail[17]. Following pathological parameters were analyzed and graded independently: H pylori infection, acute foveolitis (epithelial neutrophilic infiltration), interstitial neutrophilic infiltration, chronic interstitial inflammation (mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration in lamina propria), atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and lymphoid follicle formation. Each parameter was analyzed independently in the antrum and body. The density of H pylori was scored from grades 1 to 3 according to the Sydney system[12]. In most biopsies, H & E staining was enough to evaluate the H pylori infection. Giemsa and/or Warthin-Starry staining were done when confirmation was necessary.

Acute foveolitis was defined rather strictly to exclude nonspecific infiltration. It was counted to be positive when any of the following 3 criteria was fulfilled: an aggregate of more than 5 neutrophils within the epithelium (patchy infiltration), more than 10 neutrophils infiltrating a pit or gland circumferentially (diffuse infiltration) and/or an inflammatory exudate with more than 5 neutrophils in the lumen (pit abscess).

The interstitial neutrophilic and/or lymphoid infiltration, mucosal atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia were scored as follows: 0, no evidence of the lesion; 1, mild; 2, moderate to severe. The presence of lymphoid follicle was scored as 1.

Immunohistochemical staining for Ki-67 was done to delineate the histological zones of the mucosa. Paraffin sections, 3 μm-thick, were applied to microwave antigen retrieval in 0.01 mol/L sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Rabbit anti-Ki67 antiserum (A0047) was purchased from Dako (Carpinteria, CA). Avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex was developed by immersing slides in diaminobenzidine as chromogen and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Statistical analysis was done using χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test.

Biopsies were selected randomly from those having histopa-thologically proven H pylori infection. The mean ages of the populations were not significantly different. However, the gender distribution was significantly different. Male subjects consisted of 47.4% of the American population, while 77.9 and 67.4% were males in the Japanese and Koreans respectively (P <0.001).

All biopsies contained H pylori-like organisms at the mucosal surface. The density of organisms was graded as described. In Americans, grades 1, 2, and 3 were 30.6%, 18.4%, and 51.0% respectively. In Japanese, grades 1, 2, and 3 were 20.8%, 37.5%, and 41.7% respectively. In Koreans, grades 1, 2, and 3 were 35.6%, 25.5%, and 38.9% respectively. Although grade 3 appeared to be frequent in Americans, no statistical difference was noted among the populations.

Acute foveolitis was frequently present at the proliferative zone of the gastric pit in all populations (Figure 1). As shown previously[17-19], Ki-67 expressing epithelial cells located only in the proliferative zone (data not shown). In the surface epithelium and deep glandular zone, neutrophilic infiltration was rare and did not fit the criteria described in the Materials and Methods.

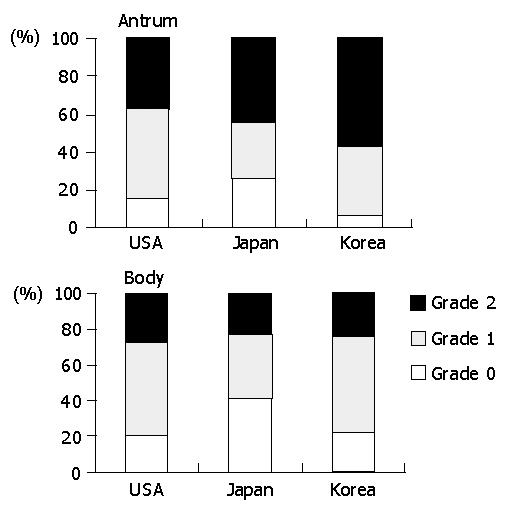

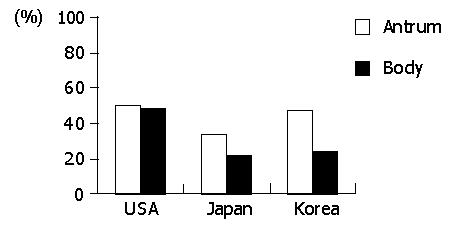

The prevalence of acute foveolitis varied considerably among the populations (Figure 2). In the antrum, the prevalence of acute foveolitis was 82.5% in Koreans followed by Japanese (71.4%) and Americans (61%) (P<0.01). In the body, acute foveolitis was present in 64.3% of Americans followed by Koreans (57.9%) and Japanese (54.2%). However, the difference was not statistically significant.

The prevalence of acute foveolitis varied depending on the topographical location in a population (Figure 2). In Koreans, acute foveolitis was more frequent in the antrum (82.5%) than in the body (57.9%) (P<0.01). The Japanese also had antrum-predominant acute foveolitis (71.4% versus 54.2%) (P<0.01). In Americans, however, no statistical difference was noted between the antrum and body.

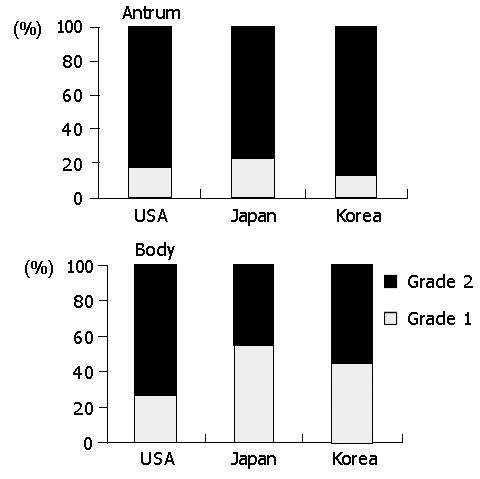

Neutrophils scattered frequently not only in the epithelium but also in the lamina propria. In the lamina propria, neutrophils were frequently concentrated in the vicinity of acute foveolitis, suggesting that they were in the process of migrating to the epithelium (Data not shown). The prevalence of interstitial neutrophilic infiltration tended to correlate with that of acute foveolitis in all populations (Figure 3). In the antrum, the interstitial neutrophilis infiltration was present in 92.7% of Koreans, followed by Americans (84.2%) and the Japanese (73.3%) (P<0.01). High-grade infiltration (grade 2) was more frequent in Koreans (56.9%) than in Japanese (43.8%) and Americans (37.7%), respectively (P<0.01). In the body, however, the interstitial neutrophilic infiltration was more frequent in Americans (78.6%) and Koreans (77.6%) than in Japanese (58.5%) (P<0.01).

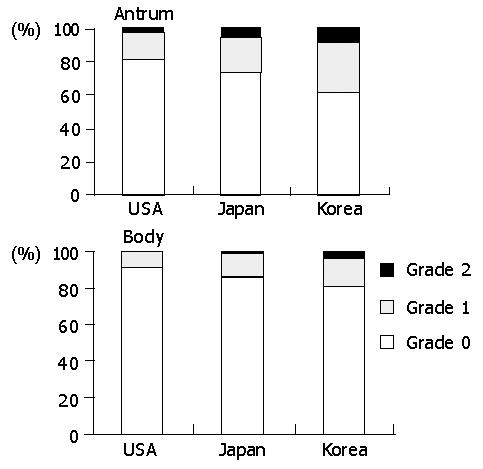

Inflammatory mononuclear infiltration was consistently observed in all biopsies. Lymphocytes were mostly in the lamina propria while intraepithelial infiltration was rare. Plasma cells were only in the lamina propria. Chronic inflammation did not appear to be associated with acute foveolitis. In the body, the intensity of chronic inflammation was significantly higher in Americans than in other populations (P<0.01). The high-grade infiltration was present in 72.6% of Americans, followed by Koreans (55.1%) and Japanese (44.9%) (Figure 4). In the antrum, the high-grade infiltration was 81.6%, 86.1% and 78.1% in Americans, Koreans, and Japanese, respectively. However, the difference was not statistically significant.

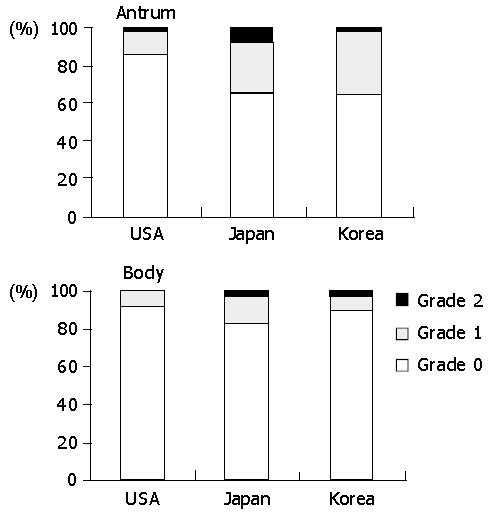

The prevalence of intestinal metaplasia varied among the populations (Figure 5). In the antrum, it was significantly lower in Americans (15.0%) than in Japanese (35.2%) and Koreans (35.1%) (P<0.01). In the body, it was present in 16.9% of Japanese, followed by Koreans (10.3%) and Americans (8.3%). However, the difference was not statistically significant.

The prevalence of mucosal atrophy varied depending on the topographical location (Figure 6). In the antrum, it was the most frequent in Koreans (38.7%), followed by Japanese (26.7%) and Americans (18.5%) (P<0.01). The intensity was also in the same order. In the body, they were 18.7%, 14.5%, and 8.3% in Koreans, Japanese, and Americans, respectively. However, no statistical difference was present.

Lymphoid follicles were common in all populations (Figure 7). In the body, the follicle formation was most frequent in Americans (47.6%), followed by Koreans (24.3%) and Japanese (21.2%) (P<0.001). In the antram, it was 50.0%, 46.0%, and 33.3% in Americans, Koreans, and Japanese, respectively. The difference was not statistically significant in the antrum.

Clinicopathological features of H pylori gastritis vary considerably among the populations. In the Korean and Japanese populations, males are about twice as many as females. The reason for male-preponderance of H pylori gastritis in those countries is not clear. It might reflect that males tend to be exposed to more outside activities including eating. However, unidentified factors in the host or genetic variations of organisms may be involved in the sex preference in H pylori gastritis in different populations[21,22]. Whatever the underlying mechanism, the male-dominant gender ratio of H pylori gastritis in Koreans and Japanese correlates with gastric cancer incidence[5-8].

There are a few reports describing geographical difference of H pylori gastritis. In a comparative study between Chinese and Dutch populations, Chen et al[23] reported that atrophy and intestinal metaplasia were more severe and occurred earlier in Chinese subjects with H pylori gastritis. El-Zimaity et al[24] also reported that, among the duodenal ulcer patients, intestinal metaplasia was more frequent in Korean subjects than in other ethnic groups. The reports have focused on the intestinal metaplasia, the biological significance of which is controversial[25]. Recently, Kimura et al[31] reported that the pathological nature of gastritis among Japanese and Swedish ulcer patients was essentially identical.

Our data shows that acute foveolitis, interstitial neutrophilic infiltration, intestinal metaplasia, and atrophy are the pathological parameters that are significantly higher in Koreans and Japanese than in Americans. The differences are present in the antrum but not in the body. In comparison with Koreans and Japanese, the body gastritis appears to be more intense in Americans, including acute and chronic interstitial inflammation, and lymphoid follicles. Thus, it can be concluded that Korean and Japanese populations have antrum-predominant gastritis whereas Americans tend to have pangastritis involving the body and antrum together. Such a topography of gastritis was reported previously in a Caucasian population[23]. However, it is not consistent with the hypothesis that gastric cancer is associated with multifocal atrophic gastritis involving both the antrum and body[24,25] and consequent decrease in the acid-secreting capacity[26]. The antral-predominance of H pylori gastritis in Koreans and Japanese is compatible with the preferred site of gastric cancer incidence[9].

Our results suggest that neutrophilic infiltration is of primary importance in the pathobiology of H pylori gastritis and gastric carcinogenesis. It is consistent with a previous report that gastritis of South Americans was more severe and of neutrophilic infiltration predominantly in comparison with North Americans[27]. However, the number of cases was limited, and the pathological nature of acute inflammation was not characterized in the study.

As described previously, acute foveolitis and interstitial neutrophilic infiltration strongly correlate with each other[17,18]. Neutrophils in the lamina propria are frequently concentrated in the vicinity of acute foveolitis, suggesting that they are in the movement targeting the epithelium. Thus, acute foveolitis appears to reflect a specific neutrophilic chemotaxis to the epithelium that has a fundamental significance in the pathobiology of H pylori gastritis[17-19].

H pylori-induced acute foveolitis could cause targeted destruction of each gastric pit, which would eventually induce atrophic gastritis together as shown in our data. Then, epithelial cells would enhance the proliferative activity to regenerate the damaged mucosa. Ironically, proliferating cells are particularly vulnerable to the mutagenic pressure[28-32], which is brought in by the activated neutrophils. The reactive oxygen and nitrogen species that are produced abundantly by the neutrophils would induce extensive DNA damage in the proliferating cells nearby[17-19]. The genomic damage may be demonstrated in the malgun(clear) cell change, which has been proposed as a fertile soil for gastric carcinogenesis[18,19].

In conclusion, our data strongly suggests that acute foveolitis is a pathological factor of fundamental significance and a crucial step in H pylori-induced gastritis and carcinogenesis. It needs to be elucidated why acute foveolitis specifically localizes to the proliferative zone. The control of acute foveolitis might be much more practical and easier than the eradication of H pylori infection. Further clinicopathological and genomic studies would be required regarding the pathobiology of ethnic differences of H pylori gastritis.

| 1. | Feldman RA, Eccersley AJ, Hardie JM. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori: acquisition, transmission, population prevalence and disease-to-infection ratio. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:39-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dooley CP, Cohen H, Fitzgibbons PL, Bauer M, Appleman MD, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and histologic gastritis in asymptomatic persons. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1562-1566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Asaka M, Kimura T, Kudo M, Takeda H, Mitani S, Miyazaki T, Miki K, Graham DY. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori to serum pepsinogens in an asymptomatic Japanese population. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:760-766. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Youn HS, Ko GH, Chung MH, Lee WK, Cho MJ, Rhee KH. Pathogenesis and prevention of stomach cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 1996;11:373-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sipponen P, Marshall BJ. Gastritis and gastric cancer. Western countries. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29:579-592, v-vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Plummer M, Franceschi S, Muñoz N. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. IARC Sci Publ. 2004;157:311-326. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Fuchs CS, Mayer RJ. Gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:32-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Yamamoto S. Stomach cancer incidence in the world. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2001;31:471. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ahn YO, Park BJ, Yoo KY, Kim NK, Heo DS, Lee JK, Ahn HS, Kang DH, Kim H, Lee MS. Incidence estimation of stomach cancer among Koreans. J Korean Med Sci. 1991;6:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Genta RM, Gürer IE, Graham DY. Geographical pathology of Helicobacter pylori infection: is there more than one gastritis? Ann Med. 1995;27:595-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735-6740. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3221] [Cited by in RCA: 3622] [Article Influence: 120.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 13. | Cerutti PA. Prooxidant states and tumor promotion. Science. 1985;227:375-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1907] [Cited by in RCA: 1729] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tamir S, Tannenbaum SR. The role of nitric oxide (NO.) in the carcinogenic process. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1288:F31-F36. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Madan E, Kemp J, Westblom TU, Chaffin J, Foster AM. Histologic characteristics of Campylobacter pylori (Helicobacter pylori) mediated gastritis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1990;20:329-336. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hansing RL, D'Amico H, Levy M, Guillan RA. Prediction of Helicobacter pylori in gastric specimens by inflammatory and morphological histological evaluation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1125-1131. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Yu E, Lee HK, Kim HR, Lee MS, Lee I. Acute inflammation of the proliferative zone of gastric mucosa in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Pathol Res Pract. 1999;195:689-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee H, Jang J, Kim Y, Ahn S, Gong M, Choi E, Lee I. "Malgun" (clear) cell change of gastric epithelium in chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Pathol Res Pract. 2000;196:541-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jang J, Lee S, Jung Y, Song K, Fukumoto M, Gould VE, Lee I. Malgun (clear) cell change in Helicobacter pylori gastritis reflects epithelial genomic damage and repair. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1203-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Havard TJ, Sarsfield P, Wotherspoon AC, Steer HW. Increased gastric epithelial cell proliferation in Helicobacter pylori associated follicular gastritis. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:68-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Suerbaum S, Josenhans C, Sterzenbach T, Drescher B, Brandt P, Bell M, Droge M, Fartmann B, Fischer HP, Ge Z. The complete genome sequence of the carcinogenic bacterium Helicobacter hepaticus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7901-7906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nogueira C, Figueiredo C, Carneiro F, Gomes AT, Barreira R, Figueira P, Salgado C, Belo L, Peixoto A, Bravo JC. Helicobacter pylori genotypes may determine gastric histopathology. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:647-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen XY, van Der Hulst RW, Shi Y, Xiao SD, Tytgat GN, Ten Kate FJ. Comparison of precancerous conditions: atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in Helicobacter pylori gastritis among Chinese and Dutch patients. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | El-Zimaity HMT O, Kim JG, Akamatsu T, Gürer IE, Simjee AE, Graham DY. Geographic differences in the distribution of intestinal metaplasia in duodenal ulcer patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:666-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Genta RM, Rugge M. Review article: pre-neoplastic states of the gastric mucosa--a practical approach for the perplexed clinician. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15 Suppl 1:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bayerdörffer E, Lehn N, Hatz R, Mannes GA, Oertel H, Sauerbruch T, Stolte M. Difference in expression of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in antrum and body. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1575-1582. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Correa P, Cuello C, Duque E, Burbano LC, Garcia FT, Bolanos O, Brown C, Haenszel W. Gastric cancer in Colombia. III. Natural history of precursor lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;57:1027-1035. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Correa P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3554-3560. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection in the pathogenesis of duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer: a model. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1983-1991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bertram TA, Murray PD, Morgan DR, Jerdak G, Yang P, Czinn S. Gastritis associated with infection by Helicobacter pylori in humans: geographical differences. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1991;181:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kimura K, Sipponen P, Unge P, Ekström P, Satoh K, Hellblom M, Ohlin B, Stubberöd A, Kihira K, Yube T. Comparison of gastric histology among Swedish and Japanese patients with peptic ulcer and Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:491-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cohen SM, Ellwein LB. Cell proliferation in carcinogenesis. Science. 1990;249:1007-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 775] [Cited by in RCA: 668] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Edited by Wang XL