Published online Nov 15, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3264

Revised: February 4, 2004

Accepted: March 2, 2004

Published online: November 15, 2004

AIM: To determine the genotypes and phylogeny of hepatitis B viruses (HBVs) in asymptomatic HBV carriers, and the prevalence of occult HBV infection in Long An County, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, an area with a high incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma.

METHODS: A nested polymerase chain reaction (nPCR) was used for detection of HBV DNA in serum samples from 36 blood donors with asympmatic HBV infection, and in serum samples from 52 HBsAg negative family members of the children who did not receive hepatitis B vaccination in Long An County. PCR products were sequenced, and the genotype of each HBV sequence was determined by comparison with sequences of known genotypes in the GenBank and EMBL nucleotide databases using the BLAST programme. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by the quartet maximum likelihood analysis using the TreePuzzle software.

RESULTS: Twenty (55.56%) of 36 HBV asymptomatic carriers were positive for HBV DNA. They were all genotype C by comparison with sequences of known genotypes in the GenBank and EMBL nucleotide databases. The full-length HBV DNA sequence isolated from the sample No. 624 contained 3215 bases. No interesting mutations were found in this isolate. The homology analysis showed that this strain was closer to the Vietnamese HBV genotype C strain, with a homology of 97%, compared its relation to the same genotype of HBV isolated in Shanghai. Six (11.5%) of the 52 HBsAg negative family members were positive for HBV DNA. A point mutation was found in the sample No. 37, resulting in the substitution of amino acid glycine to arginine in the “a” determinant. Other samples with positive HBV DNA did not have any unusual amino acid substitutions in or around the “a” determinant, and were attributed to the wild-type HBV.

CONCLUSION: The HBVs isolated from asymptomatic carriers of Long An County were all identified as genotype C, and the prevalence of occult HBV infection in the population of the county is as high as 11.5%. It is suggested that genotype C and persistent occult HBV infection may play an important role in the development of HCC in the county.

- Citation: Fang ZL, Zhuang H, Wang XY, Ge XM, Harrison TJ. Hepatitis B virus genotypes, phylogeny and occult infection in a region with a high incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in China. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(22): 3264-3268

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i22/3264.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3264

Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) may lead to a wide spectrum of liver diseases ranging from mild, self-limited to fulminant hepatitis in acute infection, and from an asymptomatic carrier state to severe chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in chronic infection. Human HBV, a prototype member of the family hepadnaviridae, is a circular, partially double-stranded DNA virus of approximately 3200 nt[1]. Traditionally, HBV was classified into 4 subtypes or serotypes (adr, adw, ayr, and ayw) based on antigenic determinants of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)[2]. Epidemiological studies found that the prevalence of these serotypes varied in different parts of the world. In addition, antibody to the common determinant “a” confers protection against all serotypes. Advances in molecular biology techniques revealed significant diversities in sequences of HBV isolates, accounting for allelic differences among the 4 major HBV serotypes. Based on an intergroup divergence of 8% or more in the complete nucleotide sequence, HBV has been classified into eight genotypes, designated as A to H[3-5]. Recent reports suggested that infections with HBV genotype C were associated with more severe liver diseases, including HCC, than infections with genotype B[6-8]. However, HBV genotype B was suggested to be associated with the development of HCC in Taiwanese below the age of 50 years[9].

Occult HBV infection is characterized by the presence of HBV infection with undetectable HBsAg. Undoubtedly, carriers of occult HBV may transmit the virus through blood transfusion or organ transplantation. Epidemiological and molecular studies performed since the 1980s indicate that persistent HBV infection might play a critical role in the development of HCC and in HBsAg-negative patients[10,11].

The incidence rate of HCC in Long An County, southern Guangxi, China, is about 49.9/100000, the highest in the world, and over 90% of HCC cases in the county are individuals with positive HBsAg in serum[12,13]. In this study, HBV preC and basic core promoter from 36 HBV asymptomatic carriers in Long An County were amplified and sequenced. The whole genome of a strain from one of the carriers, and genotypes and phylogeny of all the isolates were also analyzed to clarify the difference among HBV strains from different areas. In addition, 52 serum samples from family members of children without hepatitis B vaccination, with negative HBsAg, from the county were detected for HBV DNA to determine the prevalence of occult HBV infection in the population.

A total of 36 sera were obtained from asymptomatic blood donors who were infected persistently with HBV in Long An County, southern Guangxi, China. Another 52 serum samples were collected from family members of children failed to have hepatitis B vaccination from the county. Sera were tested for HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HBs, HBeAg, and anti-HBe using HBV Marker ELISA kits (produced by Xiamen Xinchuang Scientific Technology Company, Limited, Fujian, China) (Tables 1-2).

| No. | Age (yr) | Sex | HBsAg | Anti-HBs | Anti-HBc | HBeAg | Anti-HBe |

| 601 | 18 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 602 | 18 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 603 | 28 | Female | + | - | + | + | - |

| 604 | 20 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 605 | 27 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 606 | 18 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 607 | 31 | Female | + | - | + | + | - |

| 609 | 22 | Female | + | - | + | + | - |

| 610 | 19 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 615 | 38 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 618 | 22 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 619 | 20 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 621 | 24 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 622 | 28 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 623 | 30 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 624 | 25 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 629 | 28 | Female | + | - | + | + | - |

| 630 | 28 | Female | + | - | + | + | - |

| 633 | 18 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| 634 | 19 | Male | + | - | + | + | - |

| Sample No. | HBsAg | Anti-HBs | Anti-HBs Titre (mIU/mL) | HBeAg | Anti-HBe | Anti-HBc |

| 1 | - | + | 5.1 | - | + | + |

| 14 | - | + | 108.0 | - | + | - |

| 16 | - | + | 18.2 | - | + | + |

| 23 | - | + | 13.9 | - | - | - |

| 25 | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| 37 | - | - | - | - | - | + |

DNA was extracted from 85 μL serum by phenol/chloroform extraction following digestion by pronase. For preC and basic core promoter amplification: the first round of PCR 35 cycles was carried out using primers B935 (nt 1240-1260, 5’ GCGCTGCAGAAGGTTTGTGGCTCCTCTG-3’) and MDC1 (nt 2304-2324, 5’-TTGATAAGATAGGGGCATTTG-3’). For each cycle, the samples was amplified at 94 °C for 30 s, at 50 °C for 30 s, and at 72 °C for 90 s in a 50 μL reaction. The second round of 30 PCR cycles was carried out on 5 μL of the first round product using primers CPRF1 (nt 1678-1695, 5’-CAATGTCAACGACCGACC-3’) and CPRR1 (nt 1928-1948, 5’-GAGTAACTCCACAGTAGCTCC-3’) and the same reaction conditions of the first round.

For the surface gene amplification: the first round of 35 ycles PCR was carried out using primers MD14(5’-GCGCTGCAGCTATGCCTCATCTTC-3’, nt 418-433) and HCO2 (5’-GCGAAGCTTGCTGTACAGACTTGG-3’, nt 761-776). For each cycle,the samples was amplified at 94 °C for s, at 45 °C for 45 s, and at 72 °C for 2 min in a 50 μL reaction. The second round of 30 PCR cycles was carried out on 5 μL of the first round product using primers ME15 (5’-GCGCTGCAGCAAGGTATGTTG CCCG-3’, nt 455-470) and HDO3 (5’-GCGAAGCTTCATCATCCATATAGC-3’, nt 734-748) and the same reaction conditions of the first round. PCR products from the second round were confirmed by 15 g/L agarose gels electrophoresis and then purified using the Wizard (PCR Preps DNA purification system) (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cycle sequencing was carried out directly on 2 mL purified DNA using primers CPRF1 and 33P-dATP by the thermo sequenase radiolabeled terminator cycle sequencing kit (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sample NO. 624 was selected for whole genome sequencing. Its DNA was extracted from 170 μL serum by phenol/chloroform extraction following digestion by pronase. The whole HBV genome was amplified in three fragments. Primers for fragment 1 for the first and second round PCR were LSOB1, BPOLEO1 and LSBI1, and POLSEQ2. Primers for fragment 2 for the first and second round PCR were MDN5, BPOLEO1, BPOLBO2 and PSISEQ2. Primers for fragment 3 for the first and second round PCR were POLSEQ1, MDD2, POLSEQ6 and MDC1. The conditions of 30 PCR cycles were at 94 °C for 30 s, at 50 °C for 30 s, and at 72 °C for 90 s in a 50 μL reaction. PCR products from the second round PCR for each fragment were cloned into the vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands) and mini preparations of DNA made from 1.5 mL of 15 mL cultures of individual colonies by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation of the cell pellet. Plasmids with inserts were identified by digestion with EcoRI and remainder of the cultures used for extraction of DNA using a QIAprep spin kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). The purified DNA was sequenced as above. Sequencing primers for fragment 1 were LSB1, PSISEQ2, ds 2, ds, ADELN, MD14, ADELP, POLSEQ8, POLSEQ9, POLSEQ6, POLSEQ2. Primers for fragment 2 were BPOLBO2, POLSEQ4, LSOB1, POLSEQ5 and PSISEQ2. Primers for fragment 3 were POLSEQ6, B935, BPOLEO1, MDN5, B936 and MDC1 (Tables 3, 4).

| Primers | Sequence | Position (nt) |

| LSOB1 | 5’-GGCATTATTTGCATACCCTTTGG-3' | 2739-2762 |

| BPOLEO1 | 5’-CTGAGAGTCCAAGAGTCCTCT-3' | 1657-1677 |

| LSBI1 | 5’-TTGTGGGTCACCATATTCTT-3' | 2809-2829 |

| POLSEQ2 | 5’-AGCAAACACTTGGCATAGGC-3' | 1168-1188 |

| MDN5 | 5’-AGGAGGCTGTAGGCATAAAT-3' | 1774-1794 |

| BPOLEO1 | 5’-CTGAGAGTCCAAGAGTCCTCT-3' | 1657-1677 |

| BPOLBO2 | 5’-TCTTGTCTTACTTTTGGAAGA-3’ | 2216-2236 |

| PSISEQ2 | 5’-GCTGTTCCGGAATTGGAGCC-3' | 65-84 |

| POLSEQ1 | 5’-ACCAAGCGTTGGGGCTACTC-3' | 847-866 |

| MDD2 | 5’-GAAGAATAAAGCCCAGTAAA-3' | 2481-2500 |

| POLSEQ6 | 5’-TTTCACTTTCTCGCCAACTTA-3' | 1089-1109 |

| MDC1 | 5’-TTGATAAGATAGGGGCATTTG-3' | 2304-2324 |

| Primers | Sequence | Position (nt) |

| LSB1 | 5’-TTGTGGGTCACCATATTCTT-3' | 2809-2829 |

| PSISEQ2 | 5’-GCTGTTCCGGAATTGGAGCC-3' | 65-84 |

| ds2 | 5’-AGTCCGGTACGTCACCTTG-3' | 3198-1 |

| ds | 5’-TACCGAAAATGGAGAACACA-3' | 147-166 |

| ADELN | 5’-TAGTCCAGAAGAACCAACAAG-3' | 432-453 |

| MD14 | 5’-GCGCTGCAGCTATGCCTCATCTTC-3’ | 418-433 |

| ADELP | 5’-CCTGTATTCCCATCCCATCATC-3' | 597-618 |

| POLSEQ8 | 5’-TGTTTTCGAAAACTTCCTGT-3' | 943-962 |

| POLSEQ9 | 5’-ACAGGAAGTTTTCGAAAACA-3' | 943-962 |

| POLSEQ6 | 5’-TTTCACTTTCTCGCCAACTTA-3' | 1089-1109 |

| POLSEQ2 | 5’-AGCAAACACTTGGCATAGGC-3' | 1168-1188 |

| BPOLBO2 | 5’-TCTTGTCTTACTTTTGGAAGA-3' | 2216-2236 |

| POLSEQ4 | 5’-AAATGCCCCTATCTTATCAA-3' | 2305-2323 |

| LSOB1 | 5’-GGCATTATTTGCATACCCTTTGG-3' | 2739-2762 |

| POLSEQ5 | 5’-GGGTCCTTGTTGGGGTTGAAG-3' | 2979-2999 |

| B935 | 5’-GAAGGTTTGTGGCTCCTCTG-3' | 1240-1260 |

| BPOLEO1 | 5’-CTGAGAGTCCAAGAGTCCTCT-3' | 1657-1677 |

| MDN5 | 5’-AGGAGGCTGTAGGCATAAAT-3' | 1774-1794 |

| B936 | 5’-TGGAGGCTTGAACAGTAGGACAT-3’ | 1851-1874 |

| MDC1 | 5’-TTGATAAGATAGGGGCATTTG-3' | 2304-2324 |

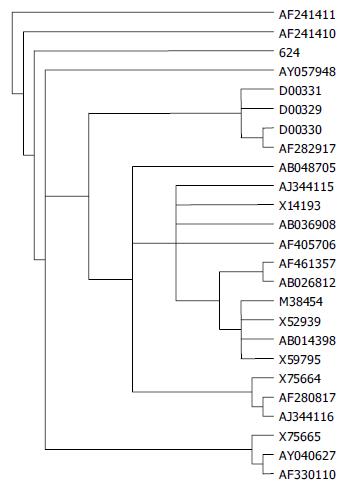

The following complete genomes (represented by their accession number) were used in phylogenetic tree analyses: genotype A: AJ344115; genotype B: AF282917, D00331; genotype C: AY040627, AF461357, M38454, AY057948, AF241410, AF241411, AF330110, AB048705, AB026812, D00329, AB014398, X75665, X14193, X52939, X59795; genotype D: AF280817, AJ344116; genotype E: X75664; genotype F: AB036908; genotype G: AF405706.

The genotype of each HBV sequence was determined by comparison with sequences of known genotypes in the GenBank and EMBL nucleotide databases using the programme BLAST[14]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by maximum likelihood analysis by quartet puzzling[15]. TreePuzzle is available at http://www.tree-puzzle.de.

Compared with sequences of known genotypes in the GenBank and EMBL nucleotide databases using the programme BLAST, all genotypes of each HBV sequence from the 20 asymptomatic HBV carriers in Long An County were found to be genotype C viruses.

The full-length HBV-DNA sequence of HBV isolated from sample No. 624 was determined by direct sequencing. This strain contained 3215 bases. Its serotype is adw. There were 40 point mutations in polymerase gene resulting in changes of 11 amino acids. There were 11, 2, 3 point mutations in PreS1, PreS2 and S genes, leading to 3, 1, 1 amino acids changed in the respective regions. The amino acid mutation in PreS1 was TPP→PHQ at codes 68-70. Six point mutations including the double mutations were found in X gene causing changes of 4 amino acids. There were also 13 point mutations in C gene, leading to 2 amino acids changed. No mutation was found in “a” determinant and Pre C.

The homology with 23 HBV strains in GenBank was determined by using the programme TreePuzzle. The HBV strain isolated from sample No. 624 in Long An County was closer to the Vietnamese HBV of genotype C, with 97% homology between them, as compared to the isolates of the same genotype from Shanghai, Beijing and Tibet in evolution (Figure 1).

After nested PCR amplification, six samples of 52 family members of children without immunization of HBV vaccine were positive for HBV DNA, counting for 11.5% (6/52) (Table 2). The region of surface ORF of the samples with positive HBV DNA positive, including the “a” determinant of HBsAg, was sequenced. A point mutation from guanosine to adenosine at nucleotide position 587 resulted in an amino acid substitution from glycine to arginine in the highly antigenic “a” determinant of HbsAg, which was found in sample No. 37 only and was negative for both HBsAg and anti-HBs. The other samples with positive HBV DNA did not have unusual amino acid substitutions in or around the “a” determinant, and were attributed to the wild-type HBV of genotype C.

In 1988, Okamoto et al[3] established a method to classify HBV, and analyzed the complete HBV nucleotide sequences and classified them into four different HBV genotypes designated from A to D, according to an intergroup divergence of > 8%, and an intragroup divergence of < 5.6%. Today, HBV has been classified into eight different genotypes designated from A to H[4,5,16,17] and HBV genotypes have a pattern of geographical distribution[18,19]. Genotype A is prevalent in Northern and Central Europe, but is also common in North America and sub-Saharan Africa. Genotypes B and C are confined to Asia, genotype D is widespread but is the predominant genotype in the Mediterranean region, while genotype E is found mainly in West Africa. Genotype F shows the highest divergence among the genotypes and is indigenous to aboriginal populations of the Americas[20]. Genotype G was found in USA and France[4], genotype H in the Central America[5], and genotypes A, B, C and D in China. The predominant genotype in China is genotypes B and C[21,22].

The incidence of HCC in Long An County is about 49.9/100000 and the prevalence of HBsAg in the county is 16%[13,23] and more than 90% of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases are individuals positive for HBsAg in serum[12]. In Japan, HBV genotype C was found to be closely associated with severe liver diseases and the development of HCC[7,24], although young HCC patients were found to be HBV genotype C in Taiwan[25].

HBV infection is usually diagnosed when the circulating HBsAg is detected. However, advances in molecular biology techniques revealed that a low level of HBV DNA could be detected in serum and liver tissue in some individuals who were negative for HBsAg[26,27]. Although there are some studies on occult HBV infection, the precise prevalence of this clinical entity is still unknown. Luo et al[28] found that the prevalence rate of occult HBV infection in Guangdong and Hainan Provinces was 2.0% (6/294) and 3.4% (68/1995), respectively in the general population. Bower et al[29] reported that the prevalence was 4.3% (11/258) in subjects without liver disease in USA. In this study, we found that the prevalence of occult HBV infection in Long An County was higher (11.5%, 6/52). The mechanisms that HBV carriers have a low, but stable level of viral replication remain to be defined. HBV strains might have mutations in S region resulting in occult HBV infection[30,31]. This kind of mutations was found in one of our samples. In addition, this type of carriers should be added to the typical HBsAg-positive carriers constituting about 16% of the general population, to estimate more precisely the propotion of asymptomatic HBV carriers in Long An County. It is clear that the prevalence of HBV infection in Long An County is in correspondence with its high incidence of HCC.

To extend the knowledge of molecular features of natural HBV isolates, sample No. 624 in this study was selected for whole genome sequencing. This strain contained 3215 bases. HBsAg region sequence showed that it belonged to serotype adw. No special mutation which could change the expression function of viral proteins was found in the sequence of this isolate. By homology analysis with 23 HBV strains in GenBank, this isolate was found to be closer to the Vietnamese HBV genotype C strain[32] than to the genotype C isolates from Shanghai in evolution[33], with 97% homology with the Vietnamese isolate. At present, the only explanation about this is that Long An County is geographically close to Vietnam.

In summary, HBV infections in Long An County are attributable to HBV genotypes C. The prevalence of occult HBV infection in Long An County is higher.

We are very grateful to the Beijing Municipal Committee of Science and Technology for the financial support in part and the Center for Disease Prevention and Control of Long An County for their help in collecting samples.

| 1. | Magnius LO, Norder H. Subtypes, genotypes and molecular epidemiology of the hepatitis B virus as reflected by sequence variability of the S-gene. Intervirology. 1995;38:24-34. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Le Bouvier GL, McCollum RW, Hierholzer WJ, Irwin GR, Krugman S, Giles JP. Subtypes of Australia antigen and hepatitis-B virus. JAMA. 1972;222:928-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Sakugawa H, Sastrosoewignjo RI, Imai M, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Typing hepatitis B virus by homology in nucleotide sequence: comparison of surface antigen subtypes. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2575-2583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 725] [Cited by in RCA: 773] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Van Geyt C, Zoulim F, Fried M, Schinazi RF, Rossau R. A new genotype of hepatitis B virus: complete genome and phylogenetic relatedness. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:67-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 563] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Arauz-Ruiz P, Norder H, Robertson BH, Magnius LO. Genotype H: a new Amerindian genotype of hepatitis B virus revealed in Central America. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2059-2073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ding X, Mizokami M, Yao G, Xu B, Orito E, Ueda R, Nakanishi M. Hepatitis B virus genotype distribution among chronic hepatitis B virus carriers in Shanghai, China. Intervirology. 2001;44:43-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fujie H, Moriya K, Shintani Y, Yotsuyanagi H, Iino S, Koike K. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1564-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Orito E, Ichida T, Sakugawa H, Sata M, Horiike N, Hino K, Okita K, Okanoue T, Iino S, Tanaka E. Geographic distribution of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype in patients with chronic HBV infection in Japan. Hepatology. 2001;34:590-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Hepatitis B genotypes correlate with clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:554-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 684] [Cited by in RCA: 700] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Paterlini P, Gerken G, Nakajima E, Terre S, D'Errico A, Grigioni W, Nalpas B, Franco D, Wands J, Kew M. Polymerase chain reaction to detect hepatitis B virus DNA and RNA sequences in primary liver cancers from patients negative for hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:80-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Paterlini P, Poussin K, Kew M, Franco D, Brechot C. Selective accumulation of the X transcript of hepatitis B virus in patients negative for hepatitis B surface antigen with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1995;21:313-321. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Yeh FS, Yu MC, Mo CC, Luo S, Tong MJ, Henderson BE. Hepatitis B virus, aflatoxins, and hepatocellular carcinoma in southern Guangxi, China. Cancer Res. 1989;49:2506-2509. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ding ZG. [Epidemiological study on relationship between hepatitis B and liver cancer--a prospective study on development of liver cancer and distribution of HBsAg carriers and liver damage persons in Guangxi]. Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi. 1988;9:220-223. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57523] [Cited by in RCA: 63668] [Article Influence: 1768.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Strimmer K, Haeseler A. Quartet puzzling: a quartet maximum-likelihood method for reconstructing tree topologies. Mol Biol Evolution. 1996;13:964-969. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1809] [Cited by in RCA: 1827] [Article Influence: 60.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Norder H, Hammas B, Löfdahl S, Couroucé AM, Magnius LO. Comparison of the amino acid sequences of nine different serotypes of hepatitis B surface antigen and genomic classification of the corresponding hepatitis B virus strains. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1201-1208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Norder H, Couroucé AM, Magnius LO. Complete genomes, phylogenetic relatedness, and structural proteins of six strains of the hepatitis B virus, four of which represent two new genotypes. Virology. 1994;198:489-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 587] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nakano T, Lu L, Hu X, Mizokami M, Orito E, Shapiro C, Hadler S, Robertson B. Characterization of hepatitis B virus genotypes among Yucpa Indians in Venezuela. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:359-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Naumann H, Schaefer S, Yoshida CF, Gaspar AM, Repp R, Gerlich WH. Identification of a new hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype from Brazil that expresses HBV surface antigen subtype adw4. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1627-1632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Norder H, Hammas B, Lee SD, Bile K, Couroucé AM, Mushahwar IK, Magnius LO. Genetic relatedness of hepatitis B viral strains of diverse geographical origin and natural variations in the primary structure of the surface antigen. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1341-1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ding X, Mizokami M, Ge X, Orito E, Iino S, Ueda R, Nakanishi M. Different hepatitis B virus genotype distributions among asymptomatic carriers and patients with liver diseases in Nanning, southern China. Hepatol Res. 2002;22:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xia G, Nainan OV, Jia Z. [Characterization and distribution of hepatitis B virus genotypes and subtypes in 4 provinces of China]. Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi. 2001;22:348-351. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Wang SS, Xu ZY, Maynard JE, Prince AM, Beasley RP, Yang JY, Li YC, Nong YZ. Evaluation of the hepatitis B model immunization program in Long An county, China. Guangxi Yufang Yixue Zazhi. 1995;1:1-4. |

| 24. | Orito E, Mizokami M, Sakugawa H, Michitaka K, Ishikawa K, Ichida T, Okanoue T, Yotsuyanagi H, Iino S. A case-control study for clinical and molecular biological differences between hepatitis B viruses of genotypes B and C. Japan HBV Genotype Research Group. Hepatology. 2001;33:218-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fujie H, Moriya K, Shintani Y, Yotsuyanagi H, Iino S, Koike K. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1564-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang JT, Wang TH, Sheu JC, Shih LN, Lin JT, Chen DS. Detection of hepatitis B virus DNA by polymerase chain reaction in plasma of volunteer blood donors negative for hepatitis B surface antigen. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:397-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhang YY, Hansson BG, Kuo LS, Widell A, Nordenfelt E. Hepatitis B virus DNA in serum and liver is commonly found in Chinese patients with chronic liver disease despite the presence of antibodies to HBsAg. Hepatology. 1993;17:538-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Luo KX, Zhou R, He C, Liang ZS, Jiang SB. Hepatitis B virus DNA in sera of virus carriers positive exclusively for antibodies to the hepatitis B core antigen. J Med Virol. 1991;35:55-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bower WA, Xia GL, Gao FX, Nainan OV, Kruszon-Moran D, Margolis HS. Isolated hepatitis B core antibody. Antiviral Ther. 2000;5:B22. |

| 30. | Bläckberg J, Kidd-Ljunggren K. Occult hepatitis B virus after acute self-limited infection persisting for 30 years without sequence variation. J Hepatol. 2000;33:992-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yamamoto K, Horikita M, Tsuda F, Itoh K, Akahane Y, Yotsumoto S, Okamoto H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Naturally occurring escape mutants of hepatitis B virus with various mutations in the S gene in carriers seropositive for antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen. J Virol. 1994;68:2671-2676. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Hannoun C, Norder H, Lindh M. An aberrant genotype revealed in recombinant hepatitis B virus strains from Vietnam. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2267-2272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Edited by Ren SY and Wang XL Proofread by Xu FM