Published online Sep 1, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2598

Revised: May 4, 2003

Accepted: May 21, 2003

Published online: September 1, 2004

AIM: To evaluate the immediate and long-term results in a series of patients with highly symptomatic polycystic liver disease (PLD) treated by combined hepatic resection with cystic fenestration.

METHODS: We reviewed our recent experience with a combined hepatic resection-fenestration procedure in seven highly symptomatic patients with PLD. Clinical data, liver manifestation of computed tomography (CT), and morbidity were recorded pre- and post-operation. Follow-up was made by clinical and CT examinations in all patients.

RESULTS: Symptomatic relief and reduction in abdominal girth were obtained in all patients during an average follow-up period of 20.4 mo. CT scans confirmed post-resection hypertrophy of the spared liver and lack of significant cyst progression. All patients had mild to severe ascites. Two patients were complicated with pleural effusion.

CONCLUSION: Some highly symptomatic patients with massive PLD may benefit from combined hepatic resection and fenestration at acceptable risk. To stitch the dissected hepatic ligaments could prevent the instable remnant liver from kinking and collapsing.

- Citation: Yang GS, Li QG, Lu JH, Yang N, Zhang HB, Zhou XP. Combined hepatic resection with fenestration for highly symptomatic polycystic liver disease: A report on seven patients. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(17): 2598-2601

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i17/2598.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2598

Polycystic liver disease (PLD) is a rare, benign inherited condition, frequently associated with polycystic disease of the kidney[1]. Unusually as liver failure appears, some patients may be highly symptomamtic due to the compression of liver enlargement or liver complications, therefore requiring treatment.

Highly symptomatic patients with PLD almost exhaust all conservative therapeutic options, and surgery is considered as the best possible procedure[2]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the immediate surgical results and the short- and long-term outcome in patients treated with hepatic resection combined with cyst fenestration on the basis of our preliminary understanding and experience.

From October 1995 to September 2002, we examined and operated on 6 women and 1 man with highly symptomatic PLD at our hospital. All operations were performed by a single surgeon (G.S.Yang). In this retrospective study, the medical records were reviewed. The mean interval from diagnosis of PLD to surgical treatment was 4.3 years, ranging from 2 to 11 years. Patient age ranged from 36-54 years, averaging 44.1 years. Specific symptoms included pain, massive abdominal distention, early satiety, regurgitation and supine dyspnea. Six patients were complicated with polycystic kidney disease but had no clinical evidence of abnormal renal function. Four patients had undergone percutaneous cyst aspiration with alcohol sclerotherapy before operation.

Preoperative workup included hematologic, hepatic and renal laboratory tests, and determinations of both respiratory and cardiovascular performance. CT scan was performed to delineate cyst distribution to assess portal vein patency and to serve as a baseline for follow-up comparison in each patient. No patient underwent angiography. The clinical features of these patients are summarized in Table 1.

| Patient no. | Age (yr) | Gender | Family history | Symptoms | Other involved organs | Previous treatment |

| 1 | 48 | Female | No siblings | Abdominal distention, regurgitation | None | None |

| 2 | 41 | Female | Father, two sisters, brother | Abdominal pain and distention | Kidney | PCA + AS (5 times) |

| 3 | 54 | Female | Sister | Early satiety, regurgitation | Kidney | PCA + AS (2 times) |

| 4 | 45 | Male | Sister | Abdominal pain and distention | Kidney | PCA + AS (2 times) |

| 5 | 43 | Female | Sister, brother, grandmother | Abdominal pain and distention, early satiety, dyspnea | Kidney | PCA + AS (2 times) |

| 6 | 36 | Female | Mother, sister | Abdominal pain and distention, early satiety, supine dyspnea | Kidney | None |

| 7 | 42 | Female | Father | Abdominal distention, regurgitation | Kidney | None |

Preoperative preparations of each patient were an overnight lavage bowel preparation and venous catheterization. The abdomen was explored through a bilateral subcostal incision. The hepatoduodenal ligament was exposed to provide access to a vascular clamping and identification of major vascular and biliary structures. The liver was mobilized by the division of hepatic peritoneal attachments, which was facilitated by sequential fenestration of accessible cysts according to the Lin technique[3]. Liver segments spared of cystic involvement were identified to define limits to resection. Non-anatomic segmental or lobar resection was executed due to cystic distortion of normal anatomy. Significant islands of functional liver parenchyma were preserved as many as possible. After resection of major cystic segments, extensive fenestration of residual cysts was performed by excision of the cyst walls. Finally, cyst cavities exposed to the peritoneum were fulgurated by argon beam coagulation (Bard Electromedical Systems, USA) in an attempt to ablate secretory epithelium and reduce postoperative peritoneal fluid losses. Cholecystectomy in conjunction with hepatectomy was performed in three patients. The hepatic resection bed was drained by two large closed suction drains. After operation, patients were sent to the surgical intensive care unit for close monitoring.

All patients were followed up through telephone calls or at clinic. Special data included hepatic and renal function, symptomatic relief, the patients' working capacity and CT scans.

The surgical outcome of our patients is presented in Table 2. The histologic examination showed von Meyenburg's complexes in all cases. There was no hospital death. All patients had ascites, the majority of them were successfully managed with diuretics and drainage within one week. The average duration of drainage was 11 d, with a range of 5-26 d. Drainage was continued by needle aspiration in Patients 5 and 6 immediately after a two-week closed suction drainage. The change was an attempt to prevent ascites from infection. Furthermore Patient 5 required thoracentesis due to left pleural effusion.

| Patient no. | Hepatic resection | Blood loss (mL) | Cystic fluid aspirated (mL) | Days of hospital stay (after operation) | Postoperative complications | Symptomatic relief | Reduction in size of liver |

| 1 | III, IVb, V | 400 | 1500 | 21 (12) | Acites | Marked | Marked |

| 2 | II, III, V | 800 | 3000 | 25 (14) | Acites | Marked | Marked |

| 3 | Right semi hepatectomy, cholecystectomy | 200 | 1200 | 16 (8) | Mild acites | Marked | Marked |

| 4 | Right smi hepatectomy, cholecystectomy | 300 | 1800 | 24 (16) | Moderate acites | Marked | Marked |

| 5 | II, III, IVb | 1500 | 6500 | 83 (29) | Severe acites,left pleural effusion | Moderate | Moderate |

| 6 | II, III, VI, VII | 3400 | 4000 | 42 (16) | Severe acites, right pleural effusion | Marked | Marked |

| 7 | II, III, VI | 300 | 2500 | 27 (11) | Acites | Marked | Marked |

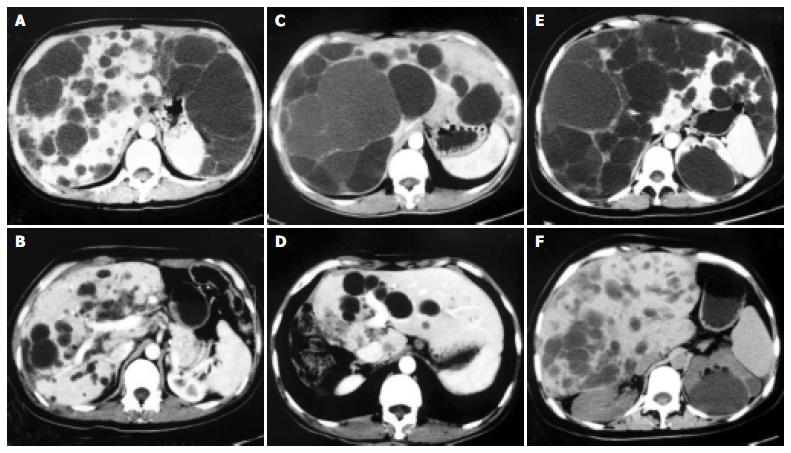

All patients experienced relief of abdominal symptoms and had normal hepatic and renal laboratory tests. Abdominal girth was reduced markedly in six patients and moderately in one. Repeated abdominal CT scans in these patients failed to show significant development of cysts in the previously spared liver segments during a mean follow-up period of 20.4 mo, with a range from 2 to 86 mo. Indeed, as shown in Figure 1, CT scans confirmed post-resection hypertrophy of the spared liver and lack of clinically significant cyst progression.

PLD is a rare disorder usually associated with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, with an increasing prevalence associated with age and female sex[4]. Symptoms arise from liver enlargement and compression of adjacent structures. Most symptomatic patients complained of increasing abdominal girth and a chronic dull abdominal pain. Liver enlargement may cause early satiety, weight loss, respiratory compromise, and physical disability. Complications such as ascites, esophageal varices, jaundice and hepatic failure, are rare[5-7].

A variety of treatment have been advocated for the few patients with incapacitating symptoms. Percutaneous aspiration with alcohol sclerotherapy seems valuable for solitary cysts but does not provide relief for patients with PLD because cyst collapse may not be sufficient[8]. Cyst fenestration with internal drainage into the peritoneal cavity, described by Lin in 1968, may fail to achieve long-term favorable outcome[9]. In practice, the efficacy of the Lin decompression for PLD is limited by extent of cysts, access to central cysts, postoperative walling off of cysts, and the rigid architecture of the fenestrated liver, which does not completely collapse[2]. Liver transplantation might be considered for patients with a "syndrome of lethal exhaustion" from PLD[7,10,11].

Armitage and Blumgart[12] described in 1984 a patient with PLD who underwent partial hepatic resection and cyst fenestration. This procedure allowed the excision of most prominent cysts with minimal resection of liver tissue; liver parenchyma was preserved despite the polycystic disease. Other reports have shown the feasibility of such an approach (Table 3)[1,2,8,12-18]. We reported a similar favorable outcome. During a mean follow-up of 20.4 mo, six of seven patients were symptom free. Herein, we emphasize that the result might be achieved by a careful selection of patients and by an experienced surgeon. The head surgeon of our surgical team has abundant experiences of more than 1400 hepatectomies for liver tumors during the same study period.

| Authors | No. of patients | Mortality (no.) | Morbidity (no.) | Follow-up (mos) | No. of symptom- free patients |

| Armitage et al[12] (1984) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 |

| Iwatsuki et al[13] (1988) | 6 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Newman et al[2] (1990) | 9 | 1 | 6 | 17 | 7 |

| Sanchez et al[8] (1991) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 2 |

| Vauthey et al[1] (1992) | 5 | 0 | 4 | 14 | 5 |

| Henne-Bruns et al[14] (1993) | 8 | 0 | 3 | 15 | 6 |

| Soravia et al[15] (1995) | 10 | 1 | 2 | 68 | 6 |

| Que et al[16] (1995) | 31 | 1 | 18 | 29 | 28 |

| Vons et al[17] (1998) | 12 | 1 | 10 | 34 | 1 0 |

| Johnson et al[18] (1999) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 1 |

| Our series | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 6 |

| Total | 92 | 4 (4.3%) | 50 (54.3%) | 72 (78.3%) |

The postoperative morbidity rate in reviewed reports was 54.3%. The majority of immediately postoperative complications in our series were ascites and transient pleural effusion. Ascites was easily treated by diuretics and effective drainage or followed by needle aspiration. None of our patients had kidney failure requiring dialysis before or after operation. Ascites occurred in the patients with renal dysfunction may be refractory and even increased the chance to be infected or bring forth malnutrition[17]. The elucidation for the mechanism of hepatic cystic epithelium secretion may be a key to solve this problem[19].

The literature review showed an overall mortality rate of 4.3%. There is only one report that the cause of death was related to this procedure for patients with PLD[15]. Acute Budd-Chiari syndrome developed shortly after fenestration of posterior cyst, which provoked a liver collapse. In practice, to stitch on the dissected triangular, falciform and round ligaments easily kept the stability of the remnant liver, which was weakened by extensive fenestration of posterior and interior cysts. Patient 6 is a good example in our series. In patients 3 and 4, we found that the left lobes twisted towards right due to gravity after right semi-hepatectomy in operation. Connecting the falciform and round ligaments easily enabled the remnants fixed, avoiding occurrence of kinking. It may be unnecessary to avoid fenestration of posterior cysts and propose a frontal hepatectomy. Two patients in literature died from postoperative intracerebral bleeding, suggesting that evaluation of selected patients' cerebral vasculature to detect aneurismal disease is essential[2,16].

Our follow-up duration is limited and our preliminary study includes just seven selected patients. Therefore, the long-term benefit of combined hepatic resection and fenestration should be further evaluated. On the basis of our experience and review of the available literature, however, this approach could be feasible, with an acceptable risk as well as a favorable long-term outcome at follow-up. To stitch the dissected hepatic ligaments could prevent the instable remnant liver from kinking and collapsing.

| 1. | Vauthey JN, Maddern GJ, Blumgart LH. Adult polycystic disease of the liver. Br J Surg. 1991;78:524-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Newman KD, Torres VE, Rakela J, Nagorney DM. Treatment of highly symptomatic polycystic liver disease. Preliminary experience with a combined hepatic resection-fenestration procedure. Ann Surg. 1990;212:30-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lin TY, Chen CC, Wang SM. Treatment of non-parasitic cystic disease of the liver: a new approach to therapy with polycystic liver. Ann Surg. 1968;168:921-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Grünfeld JP, Albouze G, Jungers P, Landais P, Dana A, Droz D, Moynot A, Lafforgue B, Boursztyn E, Franco D. Liver changes and complications in adult polycystic kidney disease. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp. 1985;14:1-20. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ratcliffe PJ, Reeders S, Theaker JM. Bleeding oesophageal varices and hepatic dysfunction in adult polycystic kidney disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288:1330-1331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wittig JH, Burns R, Longmire WP. Jaundice associated with polycystic liver disease. Am J Surg. 1978;136:383-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Washburn WK, Johnson LB, Lewis WD, Jenkins RL. Liver transplantation for adult polycystic liver disease. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:17-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sanchez H, Gagner M, Rossi RL, Jenkins RL, Lewis WD, Munson JL, Braasch JW. Surgical management of nonparasitic cystic liver disease. Am J Surg. 1991;161:113-118; discussion 113-118;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Tan YM, Ooi LL, Mack PO. Current status in the surgical management of adult polycystic liver disease. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2002;31:217-222. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Swenson K, Seu P, Kinkhabwala M, Maggard M, Martin P, Goss J, Busuttil R. Liver transplantation for adult polycystic liver disease. Hepatology. 1998;28:412-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Starzl TE, Reyes J, Tzakis A, Mieles L, Todo S, Gordon R. Liver transplantation for polycystic liver disease. Arch Surg. 1990;125:575-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Armitage NC, Blumgart LH. Partial resection and fenestration in the treatment of polycystic liver disease. Br J Surg. 1984;71:242-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Personal experience with 411 hepatic resections. Ann Surg. 1988;208:421-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Henne-Bruns D, Klomp HJ, Kremer B. Non-parasitic liver cysts and polycystic liver disease: results of surgical treatment. Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:1-5. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Soravia C, Mentha G, Giostra E, Morel P, Rohner A. Surgery for adult polycystic liver disease. Surgery. 1995;117:272-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Que F, Nagorney DM, Gross JB, Torres VE. Liver resection and cyst fenestration in the treatment of severe polycystic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:487-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vons C, Chauveau D, Martinod E, Smadja C, Capron F, Grunfeld JP, Franco D. [Liver resection in patients with polycystic liver disease]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1998;22:50-54. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Johnson LB, Kuo PC, Plotkin JS. Transverse hepatectomy for symptomatic polycystic liver disease. Liver. 1999;19:526-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Everson GT, Emmett M, Brown WR, Redmond P, Thickman D. Functional similarities of hepatic cystic and biliary epithelium: studies of fluid constituents and in vivo secretion in response to secretin. Hepatology. 1990;11:557-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Edited by Ma JY Proofread by Xu FM