INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is one of the most prevalent malignancies in China[1]. Despite the recent progress in early diagnosis and treatment of the disease, aggressive surgical or chemotherapeutic interventions have not sufficiently prolonged the survival time of patients with distant metastases[2]. Thus, searching for more effective therapeutic modalities, especially for the stage IV gastric cancer patients, has become an urgent task in our daily medical practice.

The transfer of suicide genes into tumor cells that is currently being studied as a method of treatment for various cancers has made the target cells become sensitive to the pharmacological agents. Suicide gene therapy with the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) fragment, the most widely used strategy for the cancer therapeutic study[3], has been shown to exert antitumor efficacy in various cancer models[4-7]. However, its efficacy seems not to be fully developed to eliminate tumor cells in some of the investigations[8-12]. Gene therapy with HSV-TK and cytokine genes together may produce a complementary effect, and has become a new insight for the treatment of malignancies[13,14].

Previously, we constructed two retroviral vectors, pL(TT) SN and pL(TI)SN, which have been confirmed to express TK-IRES-TNF-α and TK-IRES-IL-2 genes respectively in the gastric cancer cell line SGC7901[15]. In the present study, the synergistic antitumor effects of these vectors on human gastric cancer cells were investigated in the presence of GCV to confirm their efficiency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and vectors

The mouse fibroblast cell line NIH3T3 and the amphotropic retroviral packaging cells PA317 were the generous gifts from Dr. Yu Bing (Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China). The human gastric carcinoma cell lines SGC7901 were obtained from Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry. All of the cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FBS (Hangzhou, Sijiqing Biotech Company), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The PA317 was used as the packaging cell and the NIH 3T3 cells were employed to assay the virus titre. The cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

The recombinant vectors pL(TT)SN and pL(TI)SN, which express TK-IRES-TNF-α and TK-IRES-IL-2 genes respectively, as well as the control plasmid pL(TK)SN carrying only TK fragment were constructed and identified in our previous study[15]. The empty plasmid PLXSN used as another control vector was provided by Dr. Yu Bing (Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China).

Establishment of stable transfectants

The retrovirus plasmids pL(TT)SN, pL(TI)SN, pL(TK)SN and pLXSN were transferred into PA317 cells respectively by lipofectamine (Gibco) according to the manual instructions[16,17]. After 48 h of transfection, G418 (Promega) was added to the culture medium at a concentration of 500 mg·L-1 to select G418-resistant colonies. After 2-weeks’ culture with the changing of the G418-containing medium every 3 days, the supernatant of G418-resistant colonies was collected and diluted to different concentrations to infect NIH3T3 cells, which were further undergone the G418 selection for 2w, then the G418-resistant NIH3T3 colonies were counted for the determination of viral titre[18]. The viral titers of pL(TT)SN, pL(TI)SN, pL(TK)SN and empty plasmid pLXSN were 5 × 108 CFU/L, 6 × 108 CFU/L, 1 × 109 CFU/L and 1 × 109CFU/L respectively.

A total number of 5 × 105 SGC7901 cells were incubated in a 6-well plate for 24 h, then rinsed with serum-free RPMI 1640 medium twice and incubated with 100 μL supernatant of G418-resistant PA317 colony for 3 h. After 4-weeks’ cultivation, the G418-resistant colonies designated as SGC/TK-TNF-α, SGC/TK-IL-2, SGC/TK and SGC/0 respectively according to the transfected vectors were collected and used both to confirm the objective gene expression by Western blot and to perform other determinations.

For Western blotting, the SGC/TT and SGC/TI cells were incubated respectively in the 6-well plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/well for 24 h, followed by a further cultivation of 48 h with the culture medium replaced with 1 mL of serum-free RPMI 1640. Then the serum-free medium was totally collected, concentrated in a microconcentrator to 20 μL and subjected to electrophoresis on a 120 g·L-1 SDS/PAGE gel. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and incubated overnight in 50 mL·L-1 fat free milk in PBS at 4 °C. After washed in 10 mL·L-1 fat free milk, the membrane was incubated with monoclonal antibody of mouse anti-rhIL-2 or anti-TNF-α, followed by incubatino with horseradish peroxidate-conjugated antimouse immunoglobulin. Proteins were detected by using the ECL kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Amersham)[19].

Determination of cell apoptosis

Cell apoptosis was quantitated by the protocol of flow cytometry. Briefly, 100 μL of the observed cells (2 × 105) in binding buffer and 5 μL of FITC-conjugated annexin V/PI dual staining reagents (Annexin V-FITC kit, Pharmingen, USA) were transferred in turn into a 5 mL culture tube and incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. After 400 μL of binding buffer was added into the culture tube, the flow cytometric analysis for apoptosis was performed as soon as possible within 12 h (FACScaliber; Becton. Dickinson, USA).

Cell growth assay

Cell growth was scaled in SGC/TI, SGC/TT, SGC/TK and SGC/0 cells as described in the references[20,21]. Cells were cultured in 24-well plate (Nuc, Co) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and adjusted to a density of 1.5 × 104 cells/well at the time of determination. Cell absorbance (A) at 570nm was determined each day for 6 days. The figures obtained were used to draw a cell growth curve.

MTT assay

An MTT assay was conducted to determine the cell survival rate[22,23]. Following 24 h incubation, cells cultured in 96-well plates were treated with different concentrations of GCV (Roche Co.) and continued to be cultured for 6 d, when the MTT mixture was added to medium and the cells were incubated further for another 4 h. The absorbance of the cells was measured at a wavelength of 525nm with a microtiter plate reader. The survival rate was expressed as A/B × 100%, where A was the absorbance value from the experimental cells and B was that from the control by SGC7901 cells.

Bystander effect observation

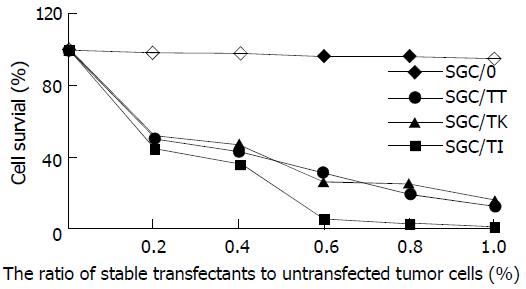

Twenty-four hours after tumor cells were infected with recombinant retrovirus, different proportions of transfected and untransfected cells that were adjusted to a density of 1 × 105 cells /well were co-cultured on 4-well flat-bottom plates at 37 °C for 5 d in the presence of 5 mg·L-1 GCV. The cell survival rate was measured by MTT method[24].

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are described as mean ± standard error of the mean. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Comparisons between means were done with the Student’s t-test. Comparison between percentages was performed with the χ2 test. A P value < 0.05 was taken as the criterion of statistical significance.

RESULTS

Expressions of stable transfectants

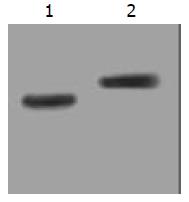

The stable expression of recombinant proteins in target cells was confirmed by Western blot, in which two distinct bands of 15ku and 17ku were observed on the nitrocellulose membrane, corresponding to the fragment sizes of IL-2 and TNF-α respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Stably expressed recombinant protein in transduced SGC7901 cells confirmed by Western blot.

Lane 1: IL-2 (15ku) expressed in SGC/TI cells; Lane 2: TNF-α (17ku) expressed in SGC/TT cells.

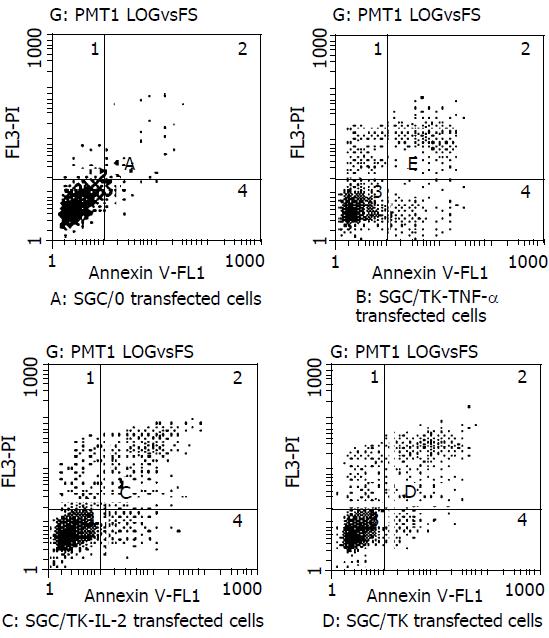

Cell apoptosis

Cells in the early phase of apoptosis were labeled by single annexin V fluorescence. The percentage of cell apoptosis in the SGC/0, SGC/TK-TNF-α, SGC/TK-IL-2 and SGC/TK clone was 2.3%, 12.3%, 11.1% and 10.9% respectively at 24 h post-transfection, indicating a slightly higher percentage of apoptosis appeared in the SGC/TK-TNF-α, SGC/TNF-α and SGC/TK clones compared with that in the SGC/0 clone (P > 0.05, Figure 2).

Figure 2 Percentage of early apoptotic cells in different groups of transfectants.

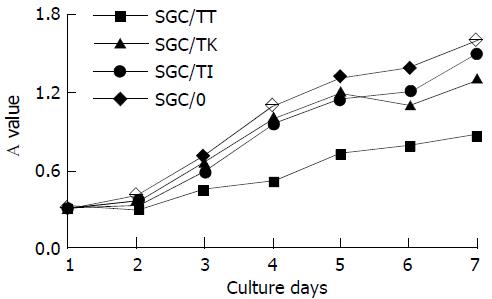

Cell growth status

The A value of cells among all experimental groups did not exhibit any significant difference (P > 0.05), although it was slightly lower in the SGC/TT group (Figure 3). The result showed that the cell growth status was not severely influenced by the vector’s variety used for the transfection in the present study.

Figure 3 Cell growth status of the different transfectants.

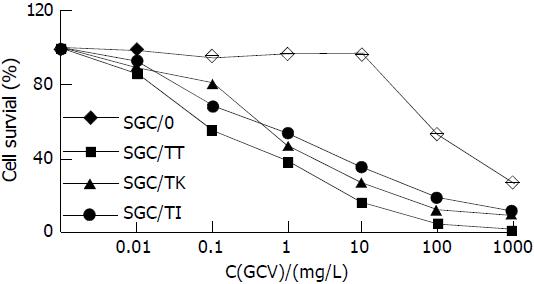

Cell viability

Cell survival rate in SGC/TI, SGC/TT and SGC/TK group was significantly decreased in a dose-dependent manner of GCV compared with that of the SGC/0 group (P < 0.05-0.01). Among all studied cells, the SGC/TT was shown most sensitive to GCV with a half lethal dose of 0.5 mg·L-1. In contrast, the survival rate of SGC/0 cells was not affected by the presence of GCV with the doses less than 10 mg·L-1. The half lethal dose of GCV for SGC/0 cells was more than 100 mg·L-1 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Cell survival rate in different experimental group treated with 5 mg·L-1 GCV for 6 d.

Bystander effect

Marked bystander effect was shown by SGC/TI, SGC/TT and SGC/TK cells as manifested by the fact that 20% of these stable transfectants could kill 50% of the co-cultured cells (Figure 5). However, the most prominent bystander effect was found in the circumstance of SGC/TT presence.

Figure 5 Bystander effect of different transfectants.

DISCUSSION

Transfer of suicide gene into tumor cells has emerged as an attractive strategy of gene therapy for the selective elimination of cancer cells, in which the suicide gene system alone or in combination with other immunological genes have been considered to be the favorable modalities for the treatment of malignancies[25-27]. The suicide genes encode non-mammalian enzymes that can convert nontoxic prodrugs into cellular toxic metabolites. The most widely used suicide gene is the HSV-TK/GCV system that can convert prodrug GCV into phosphorated GCV. The latter is further phosphorated by the cellular kinase to form GCV triphosphate, a toxic substance that can inhibit cellular DNA synthesis and lead cell to death. Besides, the “bystander effect” induced by TK gene can also enhance the tumor-killing capacity of the HSV-TK/GCV system[28-30]. However, it was found in some investigations that the antitumor efficiency of this system was limited by the lower rate of gene transfection and their insufficient induction of host immunity[31-33].

Cytokine therapy is another strategy for the treatment of malignancies. It can not only directly kill tumor cells, inhibit tumorigenesis and tumor metastasis, but can also enhance these effects by the induction of antitumor immunity. Based on the antitumor properties of certain cytokines such as IL-2 and TNF-α, it is believed that the gene therapy combining cytokine with TK suicide gene would produce more beneficial and effective effects for the treatment of cancers, which has received strong supports from some of the recently published literatures. Majumdar and his associates[33] have compared the therapeutic effect of IL-2 expression alone with that by the co-expression of IL-2 and TK genes on squamous cell carcinoma in nude mice, and found that the combined gene expression was most efficient for the gene therapy. In another study, Chen et al[34] reported that cytokine gene IL-2 could act synergistically with the suicide gene to induce a systemic antitumor immunity. Unfortunately, there have been few reports up to the present about this therapeutic strategy in the antitumor study of gastric malignancy.

In the present study, we tried to observe the antitumor effects by the co-expression of suicide gene HSV-TK and cytokine gene TNF-α or IL-2 on gastric carcinoma cell lines SGC7901. It was found that the percentage of cell apoptosis in the SGC/0, SGC/TK-TNF-α, SGC/TK-IL-2 and SGC/TK clone was 2.3%, 12.3%, 11.1% and 10.9% respectively at 24 h post-transfection, and the cell growth status as judged by cell absorbance (A) at 570nm among all the experimental groups did not exhibit any significant difference (P > 0.05), although they were noted to be slightly varied in the SGC/TT group. This indicated that the apoptosis and growth status of SGC7901 cells were not severely influenced by the vector’s variety used in the study. Whereas the cell survival rate in SGC/TI, SGC/TT and SGC/TK group was significantly decreased in a dose-dependent manner of GCV compared with that of the SGC/0 group (P < 0.05-0.01) in the presence of GCV, in which the SGC/TT cells were shown to be most sensitive to GCV with a half lethal dose of 0.5 mg·L-1. In contrast, the survival rate of SGC/0 cells was not affected by the presence of GCV with the doses less than 10 mg·L-1. The half lethal dose of GCV for SGC/0 cells was more than 100 mg·L-1. Marked bystander effect induced by SGC/TI, SGC/TT and SGC/TK cells was also confirmed by the fact that 20% of these stable transfectants could kill 50% of the co-cultured cells and the most prominent bystander effect was found in the presence of SGC/TT. However, no significant difference of these variables was found among SGC/TI, SGC/TT and SGC/TK cells, which meant that the synergistic antitumor effects produced by the co-expression of HSV-TK and TNF-α or IL-2 genes were not present in the transfected SGC7901 cells. Whether this was due to the speciality of the gastric cancer cell line is unknown. Further studies, therefore, are needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these phenomena in order to search for more efficient therapeutic modalities for the treatment of gastric malignancies.