Published online Jun 28, 2020. doi: 10.35711/aimi.v1.i1.65

Peer-review started: March 17, 2020

First decision: June 5, 2020

Revised: June 15, 2020

Accepted: June 18, 2020

Article in press: June 18, 2020

Published online: June 28, 2020

Processing time: 114 Days and 14.2 Hours

Diagnosis of a dementia subtype can be complex and often requires comprehensive cognitive assessment and dedicated neuroimaging. Clinicians are prone to cognitive biases when reviewing such images. We present a case of cognitive impairment and demonstrate that initial imaging may have resulted in misleading the diagnosis due to such cognitive biases.

A 76-year-old man with no cognitive impairment presented with acute onset word finding difficulty with unremarkable blood tests and neurological examination. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated multiple foci of periventricular and subcortical microhaemorrhage, consistent with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Cognitive assessment of this patient demonstrated marked impairment mainly in verbal fluency and memory. However, processing speed and executive function are most affected in CAA, whereas episodic memory is relatively preserved, unlike in other causes of cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer’s dementia (AD). This raised the question of an underlying diagnosis of dementia. Repeat MRI with dedicated coronal views demonstrated mesial temporal lobe atrophy which is consistent with AD.

MRI brain can occasionally result in diagnostic overshadowing, and the application of artificial intelligence to medical imaging may overcome such cognitive biases.

Core tip: This case represents the complexities of diagnosing dementia subtypes with an unusual presentation for what is likely Alzheimer’s dementia, rather than cerebral amyloid angiopathy as per initial magnetic resonance imaging brain. In such cases, imaging can potentially influence the diagnostic accuracy, which might ultimately result in misdiagnosis and hence alter the management plan. We argue that artificial intelligence and image automation could avoid such diagnostic oversights.

- Citation: Arberry J, Singh S, Mizoguchi RA. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy vs Alzheimer’s dementia: Diagnostic conundrum. Artif Intell Med Imaging 2020; 1(1): 65-69

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2644-3260/full/v1/i1/65.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.35711/aimi.v1.i1.65

Cerebral β-amyloid angiopathy (CAA) occurs when β-amyloid is deposited in the vascular media and adventitia. It is a common pathology in the brains of older individuals and is known to co-exist with other causes of cognitive decline. CAA has been shown to contribute to changes in early Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) pathogenesis[1,2]; CAA is present in 2%-3% of the AD brains of which half of them have a severe form. Therefore, it is possible that vascular change and neuritic plaque deposition are not just parallel processes but reflect additive pathological cascades.

CAA also predisposes one to cerebral infarction and cerebral haemorrhage, though the clinical effects of CAA in AD are mostly silent, or at least are ''masked'' by the greater degree of neuronal dysfunction induced by senile plaque formation and neurofibrillary degeneration. However major haemorrhagic episodes can still occur in patients with AD and CAA appears to be the underlying cause of these.

There can be diagnostic uncertainties in patients with CAA and underlying dementia. In this case report, we discuss an unusual presentation of AD. Through this we aim to emphasise the importance of robust cognitive assessment and dedicated neuroimaging in patients presenting with cognitive impairment, to investigate and consider all causes of dementia, and in order to ensure an accurate diagnosis in such patients.

A 76-year-old man presented to our hospital with acute onset word finding difficulty and “confused” speech.

He had returned from work and could not remember the events that followed. A collateral history from his wife reveals that on his return to the house, he was delirious and had difficulty word finding. There was no obvious history of trauma reported.

In the years leading up to this episode, he had small problems remembering complex instructions and would be a little more repetitive.

He had a background of hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, gout and alcohol excess, with no known cognitive impairment. He had recently had a mesenteric aneurysm repaired. He was a non-smoker.

There was no family history of note. He worked as an advisor on multiple boards and lived with his wife, both fully independent.

On general examination, there was no evidence of alcohol intoxication or alcohol withdrawal. A Glasgow Coma Scale score, which is used to review levels of consciousness, was 13 (15 is the highest score and the patient scored 2 points less due to his “confused” speech). An Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) used to assess cognition at the bedside was low at 2/10 (a score of less than 7 would prompt more sensitive cognitive testing). His neurological examination was intact aside from his speech disturbance: There was evidence of an expressive dysphasia, perseveration and confabulation. As prompted by the low AMTS, further detailed cognitive tests were carried out: (1) Montreal Cognitive Assessment, he scored 10/30 (a score of 26 or over is normal); and (2) Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination 3 (ACE3), he scored 62/100, affecting mainly memory and fluency domains (a score of 88 and above is normal; below 83 is abnormal; and between 83 and 87 is inconclusive).

All initial blood tests including full blood count, renal profile, liver function tests, ammonia, clotting screen, inflammatory markers were normal. Chest X-ray and urinalysis were normal. Electrocardiogram revealed normal sinus rhythm.

Both computed tomography (CT) brain and CT angiogram revealed bilateral hygromas without mass effect, but no other abnormality. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated bilateral infarcts, with haemorrhagic transformation. Susceptibility weighted MRI (SWI) demonstrated multiple foci of periventricular and subcortical microhaemorrhages, consistent with CAA.

On this presentation, the patient was treated as having CAA due to the MRI changes. Further diagnostic evaluation (see below), later questioned this diagnosis and raised the possibility of AD.

Given the presence of the haemorrhages on initial imaging, this patient did not receive antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy. His vascular risk factors were optimised by commencing atorvastatin and amlodipine. He was also commenced on vitamin B and thiamine tablets with his previous medications (lansoprazole, allopurinol, ferrous fumarate). He was discharged with memory clinic follow-up.

Prior to his attendance at the memory clinic, his condition was complicated by another episode of delirium and dysphasia – CT brain on this occasion demonstrated bilateral subdural haematomas, which were operated on the following day.

At the memory clinic, his repeat ACE3 reflected some degree of improvement from 62/100 to 73/100. Despite fluent speech and extensive description of historic events, the main deficits were seen again in the domains of working memory and semantic language function; he only scored 10/26 on memory domain and 5/14 on verbal fluency. This pattern of cognitive decline is consistent with AD, which is contrary to the initial diagnosis of CAA.

In this case, we are faced with multiple potential causes of cognitive decline, including AD, CAA[3,4] and intracerebral haemorrhage[4]. Gold standard diagnostic testing for AD is still post-mortem assessment of brain tissue, therefore dementia diagnosis is made based upon a combination of history, cognitive assessment and neuroimaging to provide a probable diagnosis.

Our patient demonstrated significant decline in episodic memory and verbal fluency, as per the ACE3. In recent studies[5,6], CAA has been shown to be associated with deficits in executive function and processing speed, while working memory is usually relatively preserved. Patients with AD demonstrate deficits in all domains, especially working memory. This suggests that the cognitive impairment here could represent an underlying diagnosis of AD.

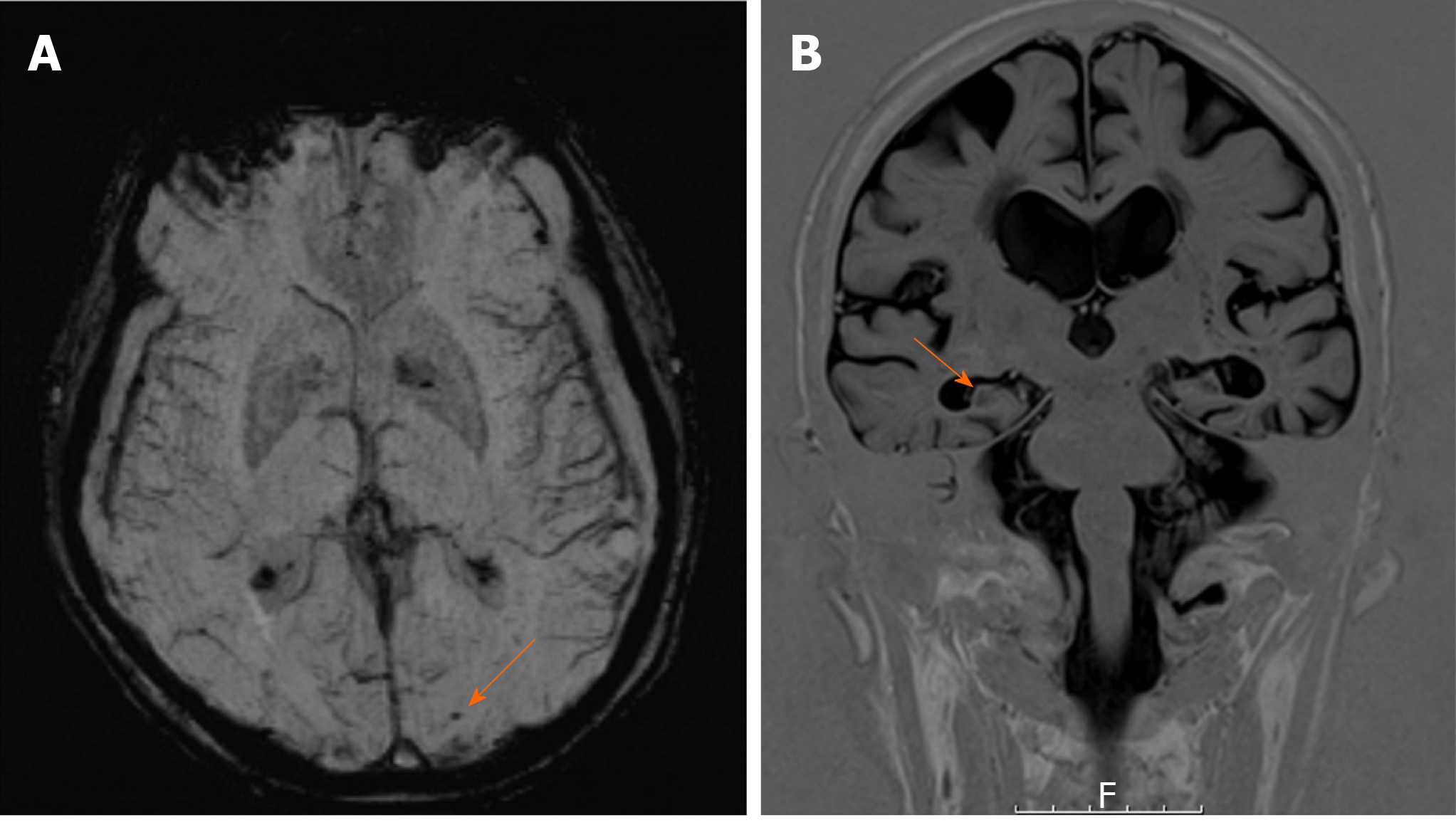

Despite this, the initial MRI brain focused significantly on features of CAA rather than mesial temporal lobe (MTL) atrophy, the latter of which correlates more with the findings on cognitive assessment. These features of CAA (microhaemorrhages) are shown more clearly on the SWI (Figure 1A), which is more sensitive at detecting CAA compared with conventional gradient-echo imaging.

Given the diagnostic overshadowing from the CAA, we proceeded to dedicated T1 coronal views of his hippocampi (Figure 1B), which demonstrated MTL atrophy. In this case, the initial MRI may have masked the potential for an alternative diagnosis of the much more likely AD. The next step would be amyloid PET scanning to add more evidence to our final diagnosis of AD.

This case highlights the perils of diagnostic oversight while reviewing imaging, resulting in the potential for misdiagnosis. It is known that the workload of radiologists has massively increased over the past decade[7], meaning they have less time to review each image. When uncertainty arises, as it did in our case, radiologists are under temporal pressure to commit to a diagnosis using their visual perception. Artificial intelligence (AI) in imaging not only removes this time pressure, but also allows image automation to remove cognitive biases that clinicians might face when reviewing imaging. Deep learning algorithms in AI allow for machines to learn how to review imaging data without the need for pre-defined human input. This increases accuracy and efficiency of image acquisition, providing objective assessment of disease and removing radiologist subjectivity. Such an approach would have assisted in the case here, and indeed would assist in all cases of cognitive impairment, by comparing imaging to a database of other age and sex matched images. Data has already demonstrated the increased sensitivity and specificity of AI techniques in diagnosis of AD with MRI[8].

There are clear diagnostic uncertainties in patients presenting with evidence of cognitive impairment and CAA. CAA has been shown to contribute to changes in early AD pathogenesis, therefore, in order to correctly diagnose the dementia subtype, robust cognitive assessment and dedicated neuroimaging is required to actively search for other causes of cognitive impairment. AI in imaging may offer a step towards accurate diagnosis in such cases using deep learning methods to provide accurate and early diagnosis of dementia subtypes.

| 1. | Vidoni ED, Yeh HW, Morris JK, Newell KL, Alqahtani A, Burns NC, Burns JM, Billinger SA. Cerebral β-Amyloid Angiopathy Is Associated with Earlier Dementia Onset in Alzheimer's Disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2016;16:218-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | De Reuck J. The Impact of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy in Various Neurodegenerative Dementia Syndromes: A Neuropathological Study. Neurol Res Int. 2019;2019:7247325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Boyle PA, Yu L, Nag S, Leurgans S, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive outcomes in community-based older persons. Neurology. 2015;85:1930-1936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Banerjee G, Wilson D, Ambler G, Osei-Bonsu Appiah K, Shakeshaft C, Lunawat S, Cohen H, Yousry T Dr, Lip GYH, Muir KW, Brown MM, Al-Shahi Salman R, Jäger HR, Werring DJ; CROMIS-2 Collaborators. Cognitive Impairment Before Intracerebral Hemorrhage Is Associated With Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Stroke. 2018;49:40-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Case NF, Charlton A, Zwiers A, Batool S, McCreary CR, Hogan DB, Ismail Z, Zerna C, Coutts SB, Frayne R, Goodyear B, Haffenden A, Smith EE. Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Is Associated With Executive Dysfunction and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Stroke. 2016;47:2010-2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xiong L, Davidsdottir S, Reijmer YD, Shoamanesh A, Roongpiboonsopit D, Thanprasertsuk S, Martinez-Ramirez S, Charidimou A, Ayres AM, Fotiadis P, Gurol E, Blacker DL, Greenberg SM, Viswanathan A. Cognitive Profile and its Association with Neuroimaging Markers of Non-Demented Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Patients in a Stroke Unit. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52:171-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McDonald RJ, Schwartz KM, Eckel LJ, Diehn FE, Hunt CH, Bartholmai BJ, Erickson BJ, Kallmes DF. The effects of changes in utilization and technological advancements of cross-sectional imaging on radiologist workload. Acad Radiol. 2015;22:1191-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Salvatore C, Cerasa A, Castiglioni I. MRI Characterizes the Progressive Course of AD and Predicts Conversion to Alzheimer's Dementia 24 Months Before Probable Diagnosis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen TL, Nassar G S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ